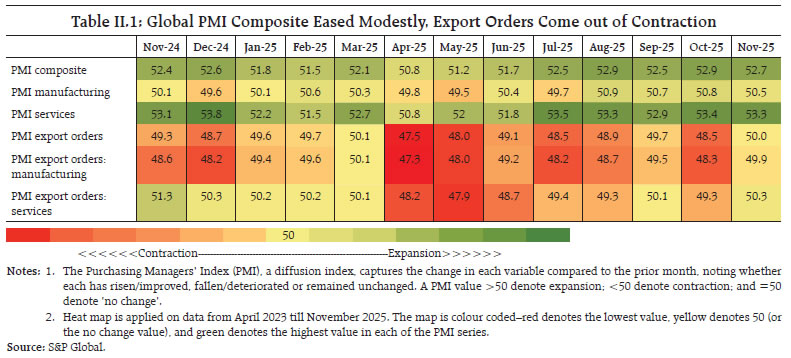

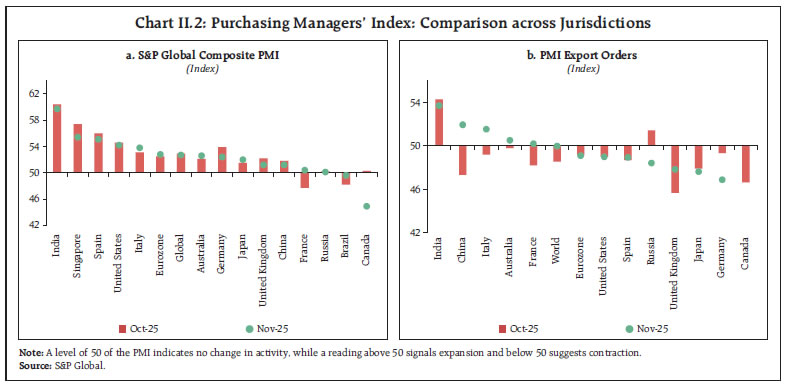

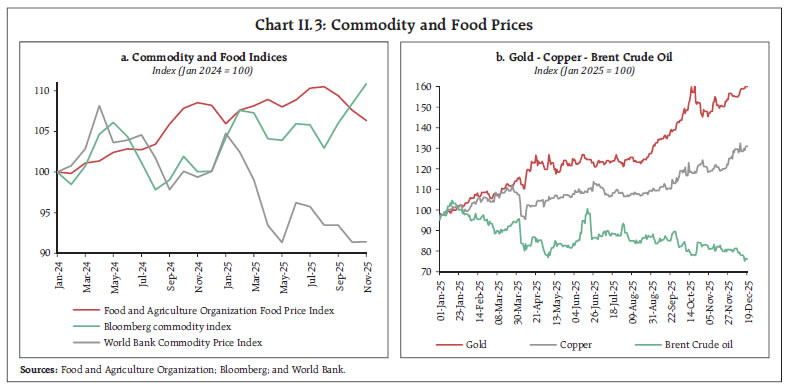

Global uncertainty retreated further from its highly elevated levels. Major equity markets experienced volatile movements due to concerns about stretched market valuations. The Indian economy, supported by resilient domestic demand in Q2:2025-26, grew at its fastest pace in the last six quarters. High-frequency indicators for November suggest that overall economic activity has held up with demand conditions remaining robust. Headline CPI inflation edged up but continued to remain below the lower tolerance level. Financial conditions remained benign, and the flow of financial resources to the commercial sector remained robust. India’s current account deficit moderated in Q2:2025-26 over the same period last year, supported by a lower merchandise trade deficit, robust services exports, and strong remittance receipts. Introduction In November, global uncertainty, including trade and policy uncertainties, retreated further from its highly elevated levels. Global economic activity expanded at a steady rate in November, aided by new export orders and the strengthening of trade in manufacturing and services. The month of November also saw China’s trade surplus reach a record of more than USD 1 trillion for the year so far. Major equity markets experienced volatile movements, particularly during mid-November, due to concerns about stretched market valuations. Portfolio flows to emerging markets turned negative for the first time after six consecutive months of positive inflows, driven by outflows from equity markets. US Treasury yields exhibited bi-directional movements, reflecting uncertainty about the Fed rate outlook for 2026, and strengthening of sentiments for a rate hike by the Bank of Japan in December. Global commodity prices barring precious metals remained largely stable. Inflation in Advanced Economies (AEs) continued to exhibit downward stickiness due to persistent services inflation. Inflation in Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs), in contrast, remained more aligned with the target. Monetary policy actions by major central banks during November gravitated towards maintaining a status quo. The month of December saw a clear divergence in the monetary policy of some systemic central banks. There are indications that central banks are nearing the end of their rate-cutting cycle, with a greater focus on data dependency going forward. The Indian economy, with a larger-than-anticipated six-quarter high GDP growth during Q2:2025-26, has demonstrated remarkable resilience amidst persistent global trade uncertainties. Domestic drivers, particularly private consumption demand, underpinned the pick-up in growth momentum. High-frequency indicators for November suggest that overall economic activity held up. Demand conditions remained robust, with indicators of urban demand strengthening further. While services sector activity continued to register strong expansion in activity, manufacturing showed some signs of deceleration. In November, the merchandise trade deficit narrowed on account of a surge in merchandise exports and a contraction in merchandise imports. Net services exports growth moderated in October, with both services exports and imports growth witnessing a slowdown in pace. Headline CPI inflation edged up in November but continued to remain below the lower tolerance level for the third consecutive month. Moderation in food deflation and the setting-in of unfavourable base effects contributed to the uptick in headline inflation. Core (i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel) inflation remained steady; however, after abstracting the impact of gold and silver prices, it fell to a new all-time low. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), in its bi-monthly review of December 2025, unanimously decided to reduce the policy repo rate by 25 bps to 5.25 per cent. The MPC also decided to maintain its neutral stance. The decisions were guided by the benign inflation outlook for both headline and core, which provided space for monetary policy to further support the growth momentum. Financial conditions remained benign with system liquidity in surplus during the second half of November and early December. The weighted average call rate – the operating target of monetary policy – remained broadly aligned with the policy repo rate. Growth in bank deposits registered an uptick in November. The total flow of financial resources to the commercial sector remained strong, bolstered by robust non-bank intermediation. Indian equity markets witnessed a rebound in the first half of November and exhibited bi-directional movements thereafter. While healthy corporate results for Q2:2025-26 and policy rate cuts by the Reserve Bank and the US Fed improved market sentiments, muted foreign portfolio flows and uncertainty surrounding the India-US trade deal weighed them down. Foreign portfolio outflows from the equity markets exerted downward pressure on the rupee; nonetheless, rupee volatility moderated in November from a month ago and remained relatively lower than that for most major currencies. India’s external sector exhibited resilience despite a challenging global environment. Current account deficit narrowed in Q2:2025-26 compared to that for the same period last year with a moderation in merchandise trade deficit, robust services trade surplus, and resilient remittances. Capital flows, however, were tempered by persistent global uncertainties. Foreign exchange reserves remain sufficient to comfortably meet India’s external financing requirements. Set against this backdrop, the remainder of the article is structured into four sections. Section II covers the rapidly evolving developments in the global economy. Section III provides an assessment of domestic macroeconomic conditions. Section IV encapsulates financial conditions in India, while Section V presents the concluding observations. II. Global Setting Global uncertainty continued to moderate in November, extending the mild retreat observed in October, even though the level of uncertainty indices remained elevated. World trade and policy uncertainties eased, supported by renewed traction in US trade negotiations and the resolution of the US government shutdown. Financial market volatility, which surged during the third week of November due to concerns about stretched AI valuations, moderated thereafter on strong corporate earnings. Volatility resurfaced during mid-December with renewed scepticism around AI investments (Charts II.1a and II.1b). The global composite PMI for November continued to indicate an expansion in economic activity, albeit at a slower rate than in the previous month. New export orders stabilised after contracting for seven consecutive months, supported by improved trade for manufactured goods and services from China following the dissipation of trade tensions between the US and China (Table II.1). Business activity, as reflected by PMI indices expanded across major AEs except Canada. Among major EMDEs, business activity expanded in India and China but contracted in Brazil. As regards new export orders, EMDEs led by India and China witnessed a fresh rise in contrast with a sustained contraction for most AEs (Charts II.2a and II.2b). Global commodity prices remained largely stable. Divergent movements were also observed across commodity markets, with a continued uptick in gold prices and a softening bias in crude oil prices. World Bank Commodity Price Index for November remained steady as lower energy prices were offset by modest increases in non-energy items. Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index declined for the third consecutive month, dragged by dairy products, meat, sugar and vegetable oils (Chart II.3a). Bloomberg Commodity price index increased further, driven by precious metals. Gold prices rose in November on Fed rate cut expectations and continued to increase further in December. Copper prices inched higher on the back of supply disruptions and price distortions due to tariff risks. Brent crude oil prices traded with a downside bias due to concerns about oversupply and growing optimism over a possible Russia-Ukraine peace deal (Chart II.3b).

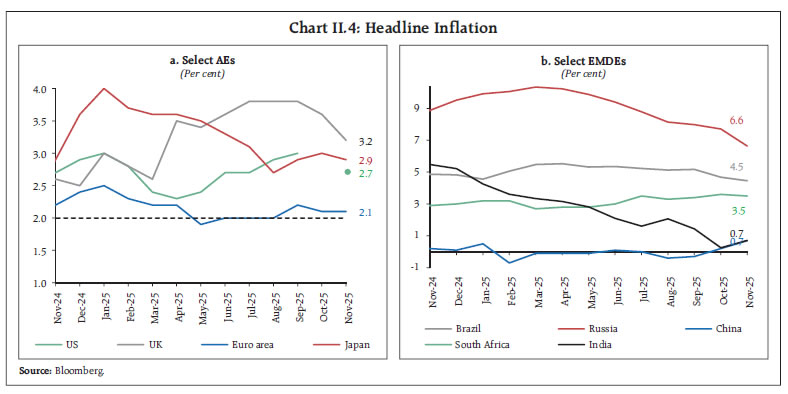

Headline inflation presented contrasting pictures across economies. Inflation eased but remained at elevated levels in AEs amidst persistent services inflation. In the Euro area, headline inflation increased further in November driven by services costs, while inflation in the US eased. Inflation in the UK fell to a six-month low led by food and beverages. Japan’s inflation also edged lower on low food inflation (Chart II.4a). Among major EMDEs, inflation picked up in China to a 21-month high driven by a rebound in food prices even as core inflation remained steady. In contrast, a lower food inflation led to easing of inflationary pressures in Brazil and in Russia, where headline inflation moderated to its lowest level since September 2023. Inflation in South Africa eased due to moderation in transport costs (Chart II.4b).

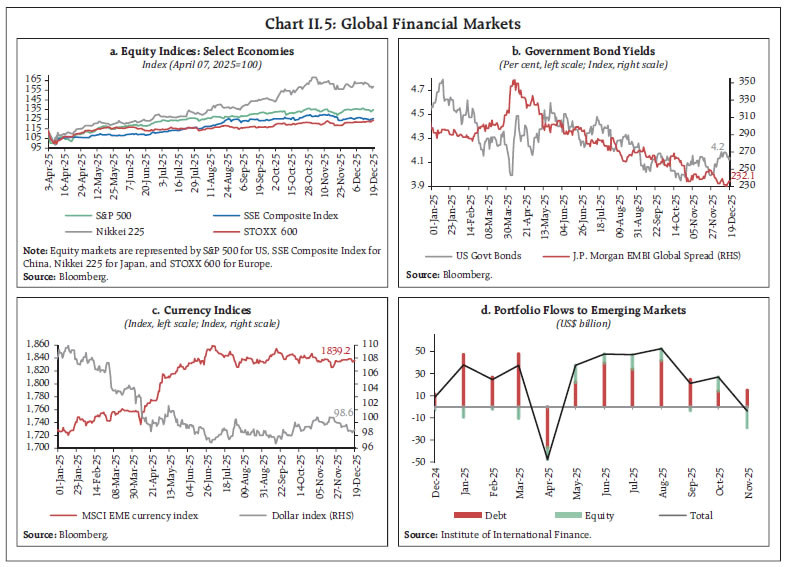

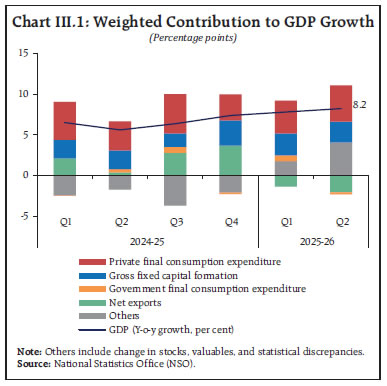

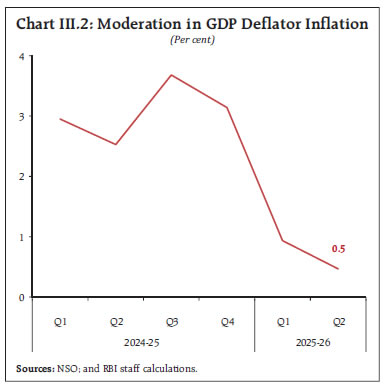

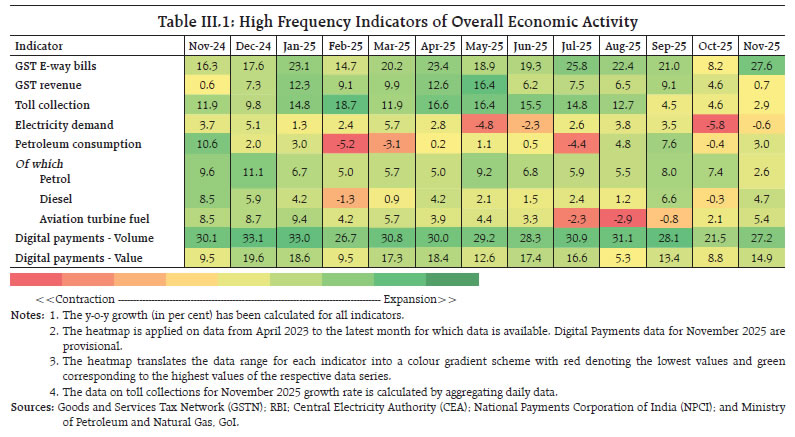

Equity markets in the US fell until the third week of November on concerns about stretched valuations of tech companies. Subsequently, markets recovered with strong corporate results and edged up in December following the Fed rate cut. However, it pared gains with the re-emergence of valuation concerns. European stocks gained during November-December on strong earnings from the financial and IT sectors, before falling as tech valuation fears resurfaced. Japan’s stock market witnessed net gains since the end of November propelled by fiscal stimulus before falling again on increasing expectations of monetary tightening. Chinese equity markets edged lower as technology stocks retreated, even as stronger than expected exports and regulatory easing for high-performing securities firms provided support (Chart II.5a). In November, US Treasury yields declined amidst increasing rate cut expectations. Yields, thereafter, firmed up to a 16-year high in early December following hawkish comments from the Bank of Japan. Though yields moderated post the Fed policy in December, the fall was capped by uncertainty on Fed rate outlook for 2026. The JP Morgan emerging market bond yield spread, on an average, narrowed sequentially in November-December so far (Chart II.5b). After moving sideways in November, the US dollar weakened in December on soft economic data and concerns about a shrinking yield advantage over other economies as Fed cut its policy rate (Chart II.5c). Portfolio flows to emerging markets turned negative in November after a six-month streak of inflows. Equity markets registered significant outflows on weak global risk appetite while debt flows remained steady and positive (Chart II.5d).  In November 2025, most major central banks kept policy rates unchanged. Among the AEs, while South Korea maintained status quo on financial stability risks, New Zealand cut the rate to an over three-year low on growth considerations. In the case of EMDEs, China, Malaysia, and Indonesia kept their interest rates unchanged in November, whereas South Africa reduced the policy rate due to concerns about growth. The month of December saw a clear divergence in the monetary policy of some systemic central banks. While the US and the UK delivered a rate cut emphasising the soft labour market conditions, Japan increased its policy rate to a 30-year high as inflation remained above target. Seven out of 15 central banks that held their meetings in December kept their key policy rates unchanged. Among the AEs, Australia, Canada, Switzerland, Euro area, and Sweden held their key rates unchanged. Amongst EMDEs, Indonesia and Brazil kept their interest rates unchanged for the third and fourth consecutive meeting, respectively. Russia, Philippines, Thailand and Mexico cut their policy rates (Chart II.6). III. Domestic Developments The Indian economy, supported by resilient domestic demand, grew at its fastest pace in the last six quarters in Q2:2025-26. On the supply side, services and industrial sectors exhibited robust growth despite the ongoing global trade and policy uncertainties. Available high-frequency indicators suggest that overall economic activity held up in the post-festival month of November. While services activity continued to register strong expansion, manufacturing showed some signs of deceleration. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), in its bi-monthly review of December 2025, unanimously decided to reduce the policy repo rate by 25 bps to 5.25 per cent. The MPC also decided to continue with the neutral stance. The decisions were guided by the benign inflation outlook for both headline and core, which provided space for monetary policy to further support the growth momentum. Aggregate Demand In Q2:2025-26, real gross domestic product (GDP) registered a growth of 8.2 per cent, the highest since Q4:2023-24, on the back of robust private consumption and fixed investment. The growth in private consumption was sustained by a robust rural demand and easing inflationary pressures. Net exports continued to be a drag on growth (Chart III.1 and Annex Table A1). Notwithstanding a sharp uptick in real GDP growth in Q2, the nominal GDP registered a four-quarter low growth of 8.7 per cent. The narrowing of the gap between nominal and real GDP growth reflected the moderation in the GDP deflator to a low of 0.5 per cent (Chart III.2). The high-frequency indicators suggest that overall economic activity held up in the post-festival month of November. While the low GST revenue collections were largely influenced by GST rate rationalisation, other available high-frequency indicators of economic activity such as e-way bills, petroleum consumption and digital payments, registered a pick-up in growth. The sharp increase in e-way bill generation indicates a rise in goods movement and freight activity supported by the GST reforms. The increase in petroleum consumption was driven by a pick-up in construction and agricultural operations. Digital payments registered robust growth in both transaction value and volume. Electricity demand declined for the second consecutive month due to the early onset of winter season (Table III.1).

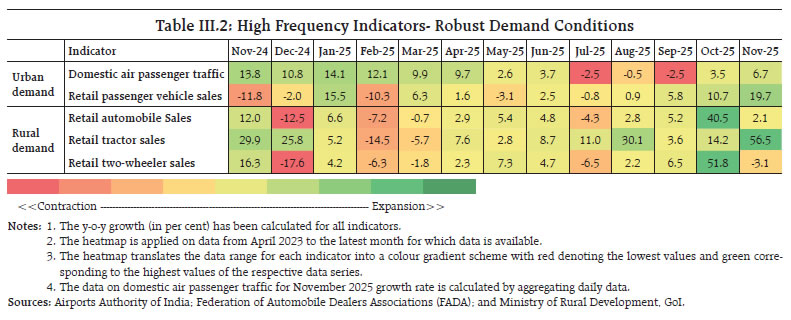

During November, overall demand conditions remained robust. Indicators of urban demand strengthened further, building up on the festival season pick-up. Retail passenger vehicle sales grew at their highest pace in over a year, aided by GST benefits, marriage season demand, and improved supply. Domestic air passenger traffic registered its fastest growth since May 2025. Retail tractor sales growth, buoyed by positive rabi season prospects, reduction in GST rates and hike in minimum support prices of rabi crops, registered a significant pick-up. Other high frequency indicators of rural demand, namely, retail automobiles sales, however, witnessed a sharp deceleration in the post festive season coupled with adverse base effects (Table III.2).1 As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey (released on December 15), the all-India unemployment rate declined to 4.7 per cent in November, with a fall in both rural and urban areas. Labour force participation rate rose to a seven-month high accompanied by an improvement in the worker population ratio. PMI employment for manufacturing witnessed deceleration in November but remained in the expansionary zone. PMI employment for services remained steady. The Naukri JobSpeak Index surged in November led by fresh hiring especially in non-IT sectors like education, hospitality, and real estate. Work demand under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) continued to contract, suggesting improvement in rural labour market conditions (Table III.3). During April-October, 2025, the Centre’s gross fiscal deficit as per cent of budget estimate (BE) was higher than the same period last financial year, while the revenue deficit as per cent of BE was lower (Chart III.3a).2 The higher fiscal deficit was driven by higher capital expenditure and contraction in net tax revenue.3 The revenue expenditure of the Centre remained flat, with interest payments registering higher growth and major subsidies recording a contraction.4 A slower growth of tax revenue was observed in both direct and indirect tax collections.5 The robust performance of non-tax revenue and non-debt capital receipts had offset the contraction in net tax revenue and supported the growth in total receipts.6 The deficit indicators of states during April-October 2025, as a proportion of BE for the financial year, were lower than the same period last year (Chart III.3b). This improvement was driven by a sharp moderation in revenue expenditure growth. Within revenue receipts, state excise growth remained strong, while SGST growth decelerated. During the year so far (April-November), the merchandise trade deficit was higher than that of last year, primarily driven by petroleum products, electronic goods and gold.7 India’s merchandise exports and imports during this period witnessed a broad-based expansion.8 In November, the merchandise trade deficit narrowed on account of a surge in merchandise exports and a contraction in merchandise imports.9 The contraction in imports in November vis-à-vis October was mainly driven by gold as the post-festive season demand declined. As a result, gold accounted for 11 per cent of merchandise trade deficit in November, down from 33 per cent in October (Chart III.4). Exports to the US increased in the month of November after declining consecutively in the previous two months.10 On December 11, Mexico imposed higher import duties ranging from 5 to 50 per cent on 1400 products imported from countries without a free trade agreement. Mexico is India’s major export destination for three sub-segments of engineering goods, namely, two and three-wheelers, motor vehicles / cars and auto components and parts.11 Mexico accounted for 5 -12 per cent of the total exports of India in these sectors during 2024-25. As India does not have a trade agreement with Mexico, tariffs on Indian exports of these goods are set to increase from 20 per cent to 50 per cent from January 1, 2026. Net services exports growth moderated in October, with both services exports and imports witnessing a slowdown in pace.12 Growth in services exports and imports softened on account of weak performance in software and transport services (Chart III.5). Aggregate Supply On the supply side, growth in real gross value added (GVA) increased to 8.1 per cent in Q2:2025-26 from 7.6 per cent in the previous quarter. The increase in GVA growth was driven by a strong pickup in industrial activity and sustained buoyancy in services sector (Chart III.6 and Annex Table A2). Industrial sector growth picked up on the back of strong performance in manufacturing. The services sector continued to sustain its growth momentum with financial, real estate and professional services being the key sub-component driving its growth. Agriculture and allied activities saw some moderation in growth on account of lower-than-expected kharif production resulting from localised crop damages due to excessive rainfall. Agriculture The first advance estimates for agricultural production of 2025-26 indicate an increase in kharif foodgrains production over the last year, driven primarily by a pick-up in cereals production–particularly rice and maize. The production of all other crops under foodgrains has declined, partially reflecting the crop damage caused by excessive rainfall (Chart III.7).13 For kharif marketing season 2025-26 so far, the procurement of rice is higher than the last year.14 Consequently, the combined stock of rice and wheat with the government remains comfortable, with a record high stock of rice.15

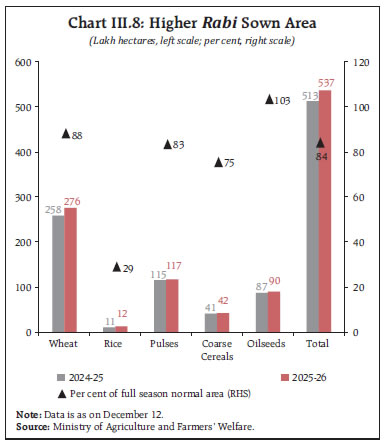

High reservoir levels, because of good post-monsoon rainfall, have supported the ongoing rabi sowing.16 Sown area under all major crops stands higher than the last year indicating better prospects for the rabi crop (Chart III.8).17 Monthly Indicators of Industrial Activity Growth in industrial activity, as measured by the year-on-year change in the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), fell to a 14-month low in October, driven by a slowdown in manufacturing output, brought about primarily by the fewer working days. Mining and electricity sectors registered contraction in October. The combined index of eight core industries remained unchanged, as growth in steel, cement, fertilisers and refinery products was offset by contractions in coal, electricity, natural gas and crude oil.  The high-frequency indicators for November point to robust industrial activity. Steel output grew strongly, reflecting continued momentum in infrastructure and construction activity. Automobile production in November registered its highest growth since February 2024 with all the segments recording double-digit growth. Two-wheeler production also rebounded after the decline in October. Stable domestic demand, coupled with GST reforms, sustained the sector’s strong growth. PMI manufacturing, though continuing to witness strong expansion, registered some deceleration due to slowdown in growth of new orders and future output prospects (Table III.4). Monthly Indicators of Services Activity India’s services sector in November continued to demonstrate a strong expansion in activity. Retail commercial vehicles sales and international air passenger traffic remained robust. Port cargo traffic registered a pick-up in growth (Table III.5). The Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) Report 202618 has ranked India as the 5th best country among G20 countries (23rd rank globally), acknowledging India’s strong progress in renewable energy. Notably, India’s adaptation-relevant expenditure as a per cent of GDP has increased significantly by 150 per cent from 2016-17 to 2022-23.19 In line with its commitment to deal with the issue of climate change, India advocated for greater adaptation finance at the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) held in November 2025.20 Inflation Headline inflation21 edged up in November to 0.7 per cent, driven by a lower rate of deflation in food prices, after reaching an all-time low of 0.3 per cent in October (Chart III.9).22

Food prices remained in deflation for the third consecutive month, although the pace of deflation moderated.23 Within food group, prices declined for vegetables, pulses and spices on a year-on-year basis. Inflation in sub-groups such as cereals, oils and fats, prepared meals and non-alcoholic beverages moderated, while that in meat and fish, eggs, milk and products, and fruits edged up (Chart III.10). Fuel and light inflation picked up to 2.3 per cent in November from 2.0 per cent in October. This was driven by kerosene PDS prices which came out of deflation after seven months. Inflation continued to remain elevated for LPG. Core (i.e., CPI excluding food and fuel) inflation remained stable at 4.3 per cent in November, the same as in October. Inflation moderated within clothing and footwear, health, recreation and amusement, education and household goods and services subgroups while inflation in pan, tobacco and intoxicants, and personal care and effects subgroups increased. Excluding precious metals, core inflation was at 2.4 per cent. Inflation in both urban and rural areas edged up in November with the latter moving out of deflation.24 Across states/UTs, inflation varied between (-) 4.2 per cent to 8.3 per cent, with the majority of states continuing to record inflation below 2 per cent. Overall, inflationary pressures were subdued across states/UTs. However, 25 out of 37 states/UTs recorded an uptick in inflation (Chart III.11). High-frequency food price data for December so far (up to 19th) point to a pick-up in cereal prices. Among pulses, gram prices moderated, while tur/arhar dal prices increased. Prices of moong remained steady. Within edible oils, the prices of sunflower oil and groundnut oil increased. Mustard oil prices were flat. Tomato and onion prices picked up while potato prices eased (Chart III.12). Retail selling prices of petrol, diesel and LPG remained unchanged in December while subsidised kerosene prices increased (up to 19th) [Table III.6]. | Table III.6: Petroleum Products Prices | | Item | Unit | Domestic Prices | Month-over-month (Per cent) | | Dec-24 | Nov-25 | Dec-25^ | Nov-25 | Dec-25^ | | Petrol | ₹/litre | 101.02 | 101.12 | 101.13 | 0.00 | 0.01 | | Diesel | ₹/litre | 90.48 | 90.53 | 90.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | | Kerosene (subsidised) | ₹/litre | 44.75 | 45.91 | 48.64 | 1.24 | 5.95 | | LPG (non-subsidised) | ₹/cylinder | 813.3 | 863.3 | 863.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ^ : For the period December 1-19, 2025.

Note: Other than kerosene, prices represent the average Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IOCL) prices in four major metros (Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai and Chennai). For kerosene, prices denote the average of the subsidised prices in Kolkata, Mumbai and Chennai.

Sources: IOCL; Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell (PPAC); and RBI staff calculations. | In November, manufacturing PMI recorded a moderation in the rate of expansion of both input and output prices. Benign inflation during the month kept input cost pressures low for firms, also limiting hikes to selling prices to maintain competitive pricing by firms in global markets. For services PMI also, deceleration continued in both input prices and selling prices as a result of the receding cost pressures and firms’ efforts to secure new business (Chart III.13).

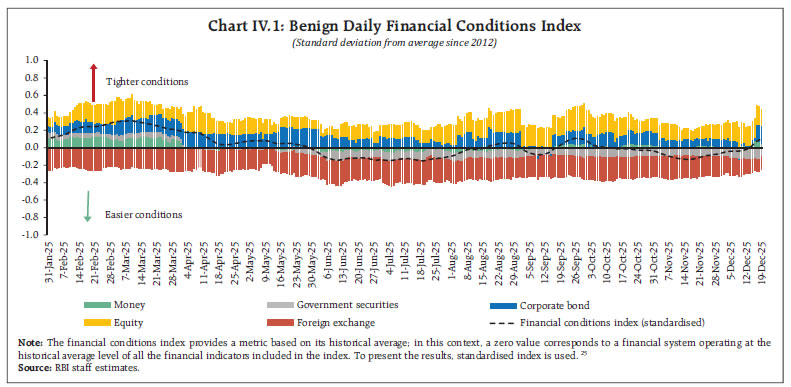

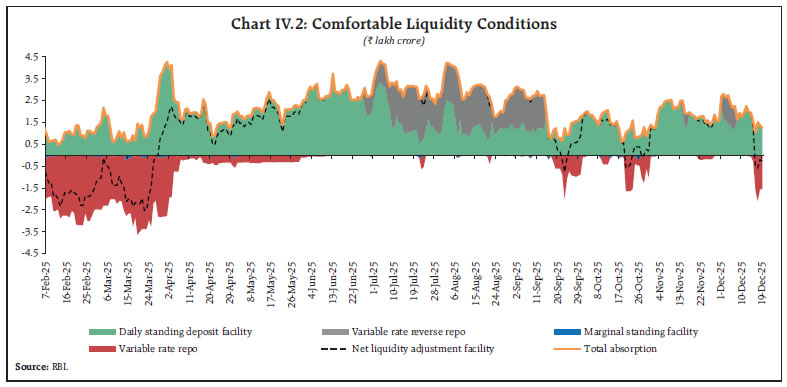

IV. Financial Conditions Overall financial conditions continued to remain benign albeit with tightening across market segments except G-sec market since the second half of November (Chart IV.1). Banking system liquidity remained largely in surplus during the second half of November and December (up to 19th). Temporary increases in government cash balances due to GST related payments and an increase in currency-in-circulation led to some decline in system liquidity during the second half of November. The last tranche of CRR reduction, effective November 29, 2025 improved liquidity conditions till mid-December. System liquidity turned into deficit in the second half of December (up to 19th) on account of buildup in government cash balances due to advance tax payments. To offset the transient liquidity tightness, the Reserve Bank conducted variable rate repo auctions. With the aim of injecting durable liquidity into the system, the Reserve Bank conducted open market operation (OMO) purchases of government securities amounting to ₹1 lakh crore and 3-year USD/INR Buy/Sell swaps of USD 5 billion in December.26  Overall, average net absorption under the liquidity adjustment facility increased to ₹1.63 lakh crore during November 16 − December 19 from ₹1.2 lakh crore in the preceding one-month period (Chart IV.2). With an improvement in the overall liquidity conditions in the first half of December, 3-day VRRRs of varying maturities were conducted to absorb surplus liquidity from the banking system. Average balances under the standing deposit facility remained marginally higher, and banks’ recourse to the marginal standing facility remained unchanged.27 Money Market The weighted average call rate (WACR) remained broadly aligned with the policy repo rate in November, despite some temporary liquidity squeezes during the latter half of November. The WACR hovered within the policy corridor as liquidity conditions improved since the beginning of December with some hardening witnessed in second half of December due to liquidity tightness. The spread of WACR over the policy repo rate, on average, remained unchanged during November 16 − December 19, compared with the preceding one-month period (Chart IV.3a). Overnight rates in the collateralised segments – as measured by the secured overnight rupee rate – moved in tandem with the uncollateralised rate. Yields on three-month treasury bills moderated, reflecting the policy repo rate cut and improved liquidity conditions. At the same time, interest rates on certificates of deposit and 3-month commercial papers issued by NBFCs remained broadly stable (Chart IV.3b). The average risk premium in the money market (the spread between the yields on 3-month commercial paper and 91-day treasury bill) recorded an uptick.28  Government Securities (G-Sec) Market In the fixed income segment, the G-sec yields softened on the day of the announcement of the policy rate cut and the Reserve Bank’s liquidity augmenting measures. Thereafter, the yields hardened amidst market perceptions of end of current easing cycle. The yields have, however, moderated marginally after the RBI’s OMO purchases of government securities on December 11 and 18, 2025.29 Compared to a month ago, the yield curve (as on December 19) shifted upwards, especially in the middle of the curve. The term spread (difference between the yields of 10-year G-sec and 91-day treasury bill) inched up marginally during the period (Charts IV.4a and IV.4b).30 Corporate Bond Market Corporate bond yields and their spreads generally witnessed mixed trends across rating spectrum and tenors (Table IV.1). New corporate bond issuances increased marginally in October. On a cumulative basis, total issuances remained higher in the current financial year so far than the same period last year.31

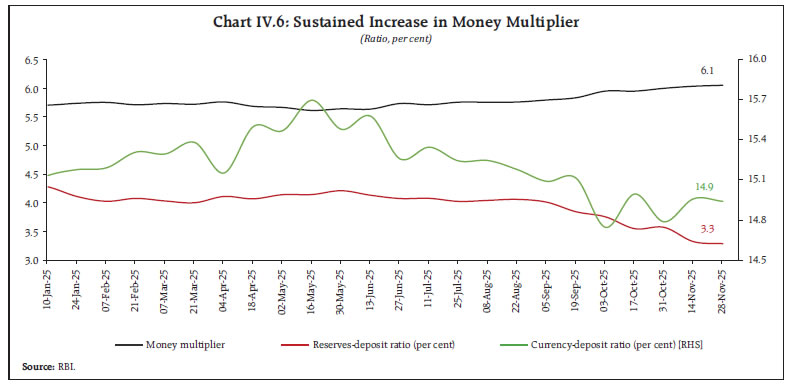

Money and Credit During November and December so far (up to 12th), growth in reserve money (adjusted for CRR) increased in tandem with the growth in currency in circulation.32 The pickup in currency in circulation was propelled by the ongoing seasonal demand, which is typically experienced in the third quarter of every financial year. Money supply (M3) also expanded at a sequentially higher pace on the back of aggregate deposits and currency with the public (Chart IV.5).33 With the cumulative reduction of 100 basis points in cash reserve ratio (CRR), phased in from September 5, banks’ reserve-deposit ratio declined over the past three months, resulting in a higher money multiplier34 (Chart IV.6). | Table IV.1: Corporate Bond Yields and Spreads Generally Softened | | Instrument | Interest Rates (Per cent) | Spread (bps) | | (Over Corresponding Risk-free Rate) | | October 16, 2025 – November 17, 2025 | November 18, 2025 – December 17, 2025 | Variation (bps) | October 16, 2025 – November 17, 2025 | November 18, 2025 – December 17, 2025 | Variation | | 1 | 2 | 3 | (4 = 3-2) | 5 | 6 | (7 = 6-5) | | (i) AAA (1-year) | 6.70 | 6.85 | 15 | 107 | 127 | 20 | | (ii) AAA (3-year) | 7.03 | 7.03 | 0 | 105 | 109 | 4 | | (iii) AAA (5-year) | 7.22 | 7.18 | -4 | 87 | 77 | -10 | | (iv) AA (3-year) | 8.10 | 8.03 | -7 | 211 | 209 | -2 | | (v) BBB- (3-year) | 11.79 | 11.68 | -11 | 574 | 574 | 0 | Note: Yields and spreads are computed as averages for the respective periods.

Source: FIMMDA. |

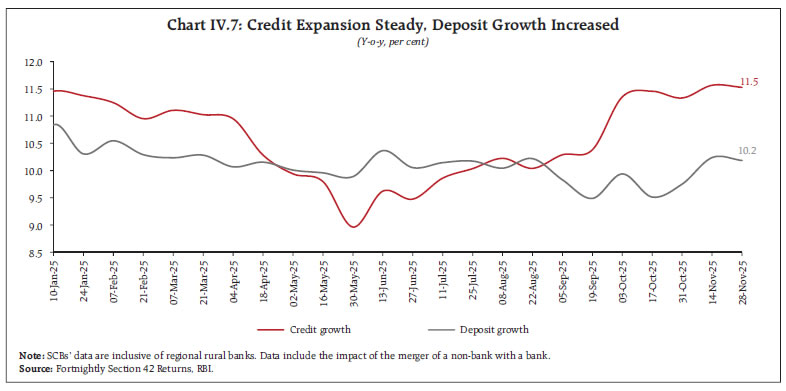

Credit growth in scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) sustained its pace during November (up to 28th) [Chart IV.7].35 Bank deposits, on the other hand, registered a significant pickup in growth. Consequently, the wedge between credit and deposit growth narrowed from 1.5 percentage points in end-October to 1.3 percentage points in end-November. During 2025-26 so far (up to November 28), the total flow of financial resources to the commercial sector remained strong, bolstered by robust greater non-bank intermediation. Non-bank sources − corporate bond issuances and foreign direct investment to India − showed a marked increase in the year so far (Table IV.2a). As on November 28, the total outstanding credit to the commercial sector rose by 13.2 per cent, with non-bank sources registering a growth of 17.0 per cent (Table IV.2b).

Bank credit growth strengthened across key sectors in October, namely, industry, services, and personal loans (Chart IV.8).36 The pick-up in industrial credit growth was driven by robust growth in credit to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). The credit to the services sector recorded buoyant double-digit growth, driven by a steep rise in banks’ lending to NBFCs. An uptick in personal loans growth came from housing and vehicle loans. Notably, loans against gold jewellery have surged and continued to record triple-digit growth rates since February 2025. The sharp expansion may be attributed to a surge in gold prices. Despite the high growth rate, the share of gold loans in overall non-food credit remains relatively low, albeit with a rise over last year.37 | Table IV.2a: Flow of Financial Resources to the Commercial Sector | | (₹ crore) | | Source | April-March | Up to November 28 | | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 P | | A. Non-Food Bank Credit | 21,40,243 | 17,98,321 | 10,48,619 | 12,40,071 | | B. Non-Bank Sources (B1+B2) | 12,63,721 | 17,10,457 | 7,86,083 | 10,16,620 | | B1. Domestic Sources | 10,20,302 | 13,85,609 | 5,85,742 | 7,48,761 | | B2. Foreign Sources | 2,43,419 | 3,24,848 | 2,00,341 | 2,67,859 | | C. Total Flow of Resources (A+B) | 34,03,964 | 35,08,778 | 18,34,702 | 22,56,691 | P: Provisional.

Note: For detailed notes, please refer to Current Statistics Table No: 18(a).

Sources: RBI; SEBI; and AIFIs. |

| Table IV.2b: Outstanding Credit to the Commercial Sector | | (₹ crore; Figures in parentheses are y-o-y percentage changes) | | Source | At End-March | As on November 28 | | 2024 | 2025 | 2024 | 2025 P | | A. Non-Food Bank Credit | 1,64,09,083 | 1,82,07,441 | 1,74,57,702 | 1,94,47,512 | | | (20.2) | (11.0) | (10.6) | (11.4) | | B. Non-Bank Sources (B1+B2) | 77,56,314 | 88,85,434 | 81,96,473 | 95,90,566 | | | (4.2) | (14.6) | (12.2) | (17.0) | | B1. Domestic Sources | 56,59,037 | 66,37,411 | 60,08,758 | 71,98,292 | | | (4.9) | (17.3) | (15.6) | (19.8) | | B2. Foreign Sources | 20,97,277 | 22,48,023 | 21,87,714 | 23,92,274 | | | (2.4) | (7.2) | (3.8) | (9.4) | | C. Total Credit (A+B) | 2,41,65,397 | 2,70,92,875 | 2,56,54,175 | 2,90,38,078 | | | (14.5) | (12.1) | (11.1) | (13.2) | P: Provisional.

Note: For detailed notes, please refer to Current Statistics Table No: 18(b).

Sources: RBI; SEBI; and AIFIs. |

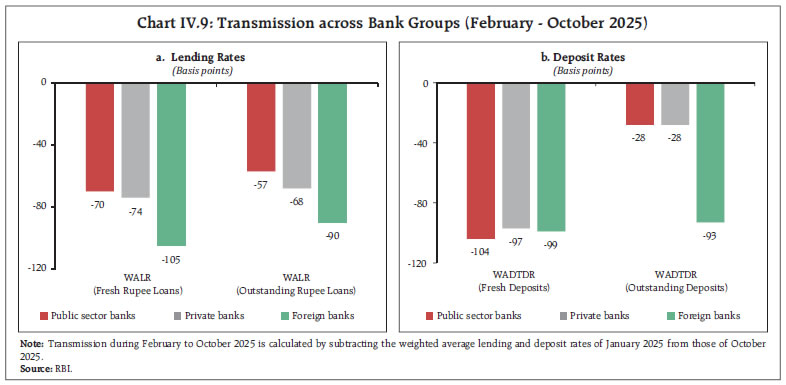

Deposit and Lending Rates In response to the cumulative 100 basis points reduction in the policy repo rate during February – October 2025, banks have reduced their external benchmark-based lending rates on fresh loans linked to repo rate by the same magnitude. The weighted average lending rates on both fresh and outstanding rupee loans also eased during this period. On the deposit side, banks reduced interest rates on fresh term deposits significantly. The pass-through to the interest rates of outstanding deposits was gradual, reflecting the effect of longer tenor of term deposits at fixed rates (Table IV.3). The decline in the weighted average lending rate on fresh and outstanding rupee loans was higher in the case of private banks relative to public sector banks (Chart IV.9). On the deposit side, transmission was higher for public sector banks compared to private banks in case of fresh term deposits. Equity Markets Indian equity markets witnessed a rebound in the first half of November and exhibited bi-directional movements thereafter. While healthy corporate results for Q2:2025-26 and policy rate cut by the Reserve Bank and US Fed supported equity markets, muted foreign portfolio flows primarily due to uncertainty surrounding the India-US trade deal and negative global cues from concerns on artificial intelligence stock valuations weighed on market sentiments. Domestic institutional investors (DIIs) remained net buyers in equity markets, while foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) turned net sellers (Chart IV.10). | Table IV.3: Transmission to Banks’ Deposit and Lending Rates | | (Basis points) | | | | Term Deposit Rates | Lending Rates | | Period | Repo Rate | WADTDR- Fresh Deposits | WADTDR- Outstanding Deposits | EBLR | 1-Year MCLR (Median) | WALR - Fresh Rupee Loans | WALR- Outstanding Rupee Loans | | Overall | Interest Rate Effect # | | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | Tightening Period

May 2022 to Jan 2025 | 250 | 259 | 206 | 250 | 175 | 182 | 191 | 115 | Easing Phase

Feb 2025 to Oct* 2025 | -100 | -105 | -32 | -100 | -50 | -69 | -78 | -63 | *: Data on MCLR as in November 2025. #: Calculated at January 2025 weights.

WALR: Weighted average lending rate; WADTDR; Weighted average domestic term deposit rate.

MCLR: Marginal cost of funds-based lending rate; EBLR: External benchmark-based lending rate.

Note: Data on EBLR pertain to 32 domestic banks.

Source: RBI. | External Sources of Finance During April-October 2025, FDI remained higher than last year both in gross and net terms. Gross inward FDI remained steady in October with Singapore, Mauritius and the US accounting for more than 70 per cent of total FDI inflows (Chart IV.11a). The highest recipients (around 60 per cent) of FDI inflows were the financial services sector, followed by manufacturing, electricity, and communication services. However, net FDI was negative in October, mainly due to high repatriation and outward FDI. The key destinations for outward FDI were Singapore, followed by the US and the UAE, together accounting for more than half of total outward FDI (Chart IV.11b). Sector specific breakdown suggests that around 90 per cent of outward FDI was in financial, insurance, and business services, followed by wholesale, retail trade and manufacturing.

During 2025-26 so far (up to December 18), net FPI registered outflows, driven by equity segment.38 FPI flows turned negative in December following inflows in the previous two months (Chart IV.12). The uncertainty surrounding India-US trade deal and investors’ caution around high domestic valuations kept net FPI flows to India muted in recent months. The registrations of external commercial borrowings (ECBs) moderated during April–October 2025, reflecting a slowdown in offshore fund raising activity.39 Net inflows from ECBs also stood lower than last year (Chart IV.13). A significant portion40 of the ECBs was mobilised for capital expenditure purpose.

India’s current account deficit moderated in Q2:2025-26 over the same period last year, supported by a lower merchandise trade deficit, robust services exports and strong remittance receipts (Chart IV.14). However, net capital inflows fell short of current account financing requirements, leading to a depletion in foreign exchange reserves.41 Nonetheless, India’s foreign exchange reserves remain adequate, providing a cover for more than 11 months of goods imports and a cover for more than 92 per cent of the external debt outstanding (Chart IV.15).42

Foreign Exchange Market The Indian rupee (INR) depreciated against the US dollar in November, pressured by the strengthening of the US dollar, muted foreign portfolio flows, and uncertainty surrounding the India-US trade deal (Chart IV.16). The volatility of INR, as measured by the coefficient of variation, moderated in November from a month ago and remained relatively lower than most major currencies. In December so far (up to 19), the INR depreciated by 0.8 per cent over its end-November level. In real effective terms, the Indian rupee remained stable in November, as depreciation of the INR in nominal effective terms was offset by higher prices in India vis-à-vis its major trading partners (Chart IV.17).

V. Conclusion The year 2025 brought about an unprecedented shift in global trade policies, marked by a move towards bilateral renegotiations on tariffs and terms of trade. Its ripple effects on global trade flows and supply chains are still unfolding. This has led to heightened global uncertainties and concerns about the prospects for global growth. Equity markets, on the other hand, remained ebullient during much of the year on Big Tech optimism, though concerns about high valuations have, of late, given rise to some risk-off sentiments in the equity markets. Portfolio flows to emerging markets are also witnessing a slowdown in recent months. The Indian economy was not fully immune to the external sector headwinds. Coordinated fiscal, monetary and regulatory policies have helped to build resilience over the year. Bolstered by strong domestic demand, the economic growth has been robust.43 Benign inflation outlook provided adequate space for monetary policy to support growth.44 Continued focus on macroeconomic fundamentals and economic reforms should help unlock efficiencies and productivity gains to firmly keep the economy on the high-growth trajectory amidst a fast-changing global environment.

Annex | Table A1: Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Growth | | (Y-o-y, per cent) | | Components | Share in 2024-25

(Per cent) | Weighted Contribution in 2024-25

(Percentage points) | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | | I. Total Consumption Expenditure | 65.6 | 4.3 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 4.7 | 7.1 | 6.5 | | Private | 56.5 | 4.0 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 7.9 | | Government | 9.1 | 0.2 | -0.3 | 4.3 | 9.3 | -1.8 | 7.4 | -2.7 | | II. Gross Capital Formation | 36.8 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 5.1 | | Fixed investment | 33.7 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 9.4 | 7.8 | 7.3 | | III. Net Exports | -0.9 | 2.3 | | | | | | | | Exports | 21.6 | 1.4 | 8.3 | 3.0 | 10.8 | 3.9 | 6.3 | 5.6 | | Imports | 22.5 | -0.9 | -1.6 | 1.0 | -2.1 | -12.7 | 10.9 | 12.8 | | GDP | 100.0 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 8.2 | Note: Components may not add up to total due to other remaining items.

Sources: NSO. |

| Table A2: Real Gross Value Added (GVA) Growth | | (Y-o-y, per cent) | | Sectors | Share in 2024-25

(Per cent) | Weighted Contribution in 2024-25

(Percentage points) | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | | I. Agriculture and allied activities | 14.4 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 3.7 | 3.5 | | II. Industry | 21.5 | 1.0 | 7.8 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 7.9 | | Mining and quarrying | 2.0 | 0.1 | 6.6 | -0.4 | 1.3 | 2.5 | -3.1 | -0.04 | | Manufacturing | 17.2 | 0.8 | 7.6 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 7.7 | 9.1 | | Electricity, gas, water supply and other utility services | 2.4 | 0.1 | 10.2 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 0.5 | 4.4 | | III. Services | 64.1 | 4.8 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | | Construction | 9.1 | 0.8 | 10.1 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 10.8 | 7.6 | 7.2 | | Trade, hotels, transport, communication, and services related to broadcasting | 18.5 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 8.6 | 7.4 | | Financial, real estate and professional services | 23.8 | 1.7 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 10.2 | | Public administration, defence and other services | 12.7 | 1.1 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 9.8 | 9.7 | | GVA at basic prices | 100.0 | 6.4 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 8.1 | | Sources: NSO; and RBI staff calculations. |

|