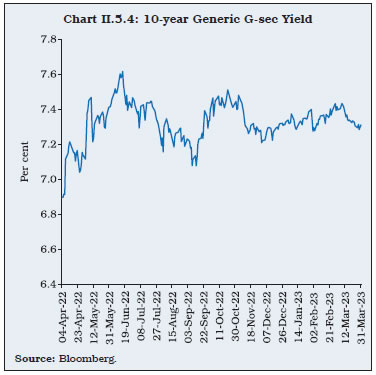

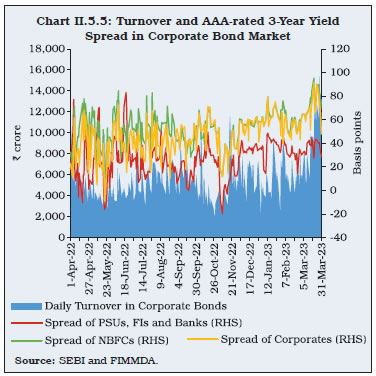

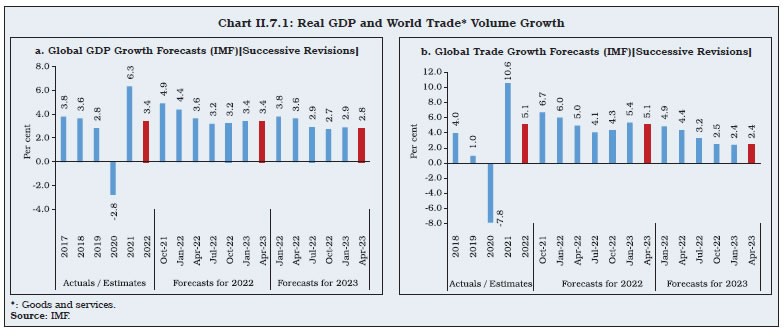

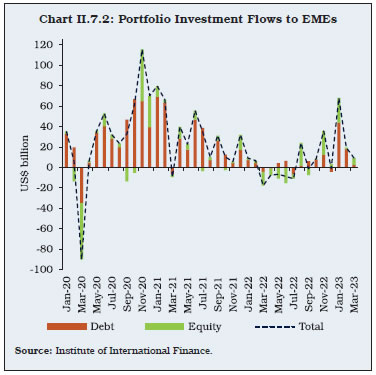

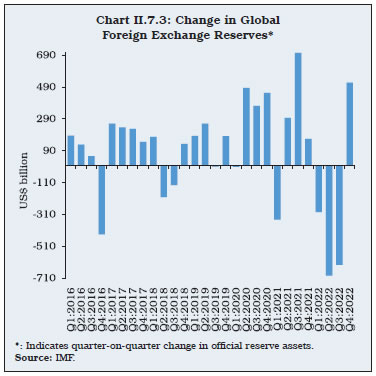

In an environment of formidable geo-economic fragmentation, elevated global food, energy and commodity prices, aggressive monetary policy tightening and spillovers, the Indian economy exhibited resilience in 2022-23. Overlapping supply shocks caused inflation to remain above the upper tolerance level of the inflation target for several months during the year. With the Reserve Bank acting pro-actively to tame inflation, monetary and credit conditions evolved in sync with the policy stance, even as targeted fiscal measures to contain inflation and fiscal consolidation strengthened macroeconomic stability. The current account deficit in the balance of payments remained sustainable and the health of the financial sector improved enabling a rebound in credit growth. II.1.1 The flaring up of geopolitical hostilities followed by a tightening of financial conditions on account of aggressive monetary policy actions worldwide dampened global macroeconomic outcomes during 2022 amidst heightened uncertainty. After the short-lived Omicron wave and a successful inoculation drive on a world-wide scale, with 64.20 per cent of world population fully vaccinated as on March 31, 2023, the resilience of the global economy stood out, causing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to revise estimate of global growth for 2022 to 3.4 per cent in April 2023 from 3.2 per cent in October 2022. However, global trade (goods and services) growth for 2022 was revised down to 5.1 per cent in April 2023 from 5.4 per cent in January 2023. Global inflation remained uncomfortably high at 8.7 per cent in 2022, as against 4.7 per cent a year ago with inflation overshooting the target in an overwhelming majority of countries. Capital flows to emerging market economies (EMEs) remained subdued and volatile. II.1.2 The synchronised tightening of financial conditions across the globe was reflected in a sharp rise in sovereign bond yields. Other segments of the financial markets also witnessed amplified volatility, reflecting the impact of global spillovers amidst pervasive risk-off sentiments. The relentless appreciation of the US dollar exerted sustained depreciation pressures on currencies of other advanced economies (AEs) and EMEs, eroding a significant part of the foreign exchange reserve buffers of countries due to valuation losses. II.1.3 Turning to the domestic economy, a recovery gained momentum during the second quarter of 2022-23 as domestic supply chains normalised and activity in contact-intensive sectors rebounded. Robust balance sheets of the corporate sector and banks enabled a rebound in credit demand, which was also facilitated by a large increase in capex by the centre. With real GDP growing by an estimated 7 per cent, the Indian economy turned out to be one of the fastest growing major economies of the world during 2022-23. II.1.4 Headline CPI inflation, which was projected by the Reserve Bank before the war started in Ukraine to moderate to 4.5 per cent in 2022-23, surged to 6.7 per cent. The elevation in price pressures was broad based and sticky, exceeding the upper tolerance level of the inflation target in several months of the year. The Reserve Bank raised the policy repo rate cumulatively by 250 basis points (bps) and changed the monetary policy stance to withdrawal of accommodation, prioritising price stability while remaining mindful of growth. In view of the dominance of supply side factors in shaping the inflation trajectory, the government introduced several targeted item specific anti-inflationary measures. Fiscal policy demonstrated a commitment to consolidation while directing public expenditure towards a large increase in growth-supportive capex. Capital formation emerged as a lead driver of growth during 2022-23. II.1.5 Financial conditions remained supportive amidst moderation in surplus liquidity during the year. Money market interest rates rose, broadly in tandem with the policy repo rate movements. Medium to long-term sovereign bond yields hardened under the impact of global spillovers, but the term premium remained below pre-COVID levels. Corporate bond yields hardened during 2022-23, tracking the rise in benchmark G-sec yields, and higher credit spreads. Equity markets exhibited resilience despite heightened global uncertainties, occasionally decoupling from global equity market movements. The Indian rupee was impacted by the strengthening of the US dollar during 2022-23, amidst risk-off sentiments driving net portfolio outflows. II.1.6 Against this backdrop, the rest of the chapter is structured into six sections. An analysis of real economy is presented in section 2, followed by movements in commodity prices and a detailed analysis of the drivers of inflation in section 3. Developments in monetary aggregates and financial markets are presented in sections 4 and 5, respectively. Government finances (centre and states) are discussed in section 6, followed by an analysis of external sector developments in section 7. II.2 THE REAL ECONOMY II.2.1 The Indian economy exhibited robust resilience in 2022-23 amidst a global turmoil following the war in Ukraine, and recorded a growth of 7.0 per cent, the highest among major economies in the world. Barring the Omicron wave scare early in the year 2022, COVID-19 was largely on the ebb for most part of the year helping in restoration of consumer and business confidence. Contact-intensive activity gradually resuscitated during the year and the release of pent-up demand bolstered domestic activity. Sound macroeconomic fundamentals, a resilient financial system reflected in healthy balance sheets of banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), and a deleveraged corporate sector imparted resilience to counter the adverse global spillovers. II.2.2 In this section, component-wise analysis of aggregate demand is presented in sub-section 2. An assessment of developments in aggregate supply conditions in terms of the performance of agriculture, industry and services are discussed in sub-section 3. A drill-down into employment and labour market developments is presented in sub-section 4. The final sub-section provides policy perspectives. 2. Aggregate Demand II.2.3 The second advance estimates (SAE) of national income that were released by the National Statistical Office (NSO) on February 28, 2023 indicated that aggregate demand, measured by real GDP, registered a growth of 7.0 per cent in 2022-23 vis-à-vis 9.1 per cent growth a year ago (Table II.2.1 and Appendix Table 1). With this, real GDP in level terms surpassed the pre-pandemic level of 2019-20 by 9.9 per cent. For the previous three years, GDP growth numbers were revised up by 20 bps (2019-20), 80 bps (2020-21) and 40 bps (2021-22) indicating that the growth momentum was stronger than what early estimates suggested. While both consumption and investment demand gained traction, adverse external demand conditions and the resultant larger deficit in net exports dragged down growth in 2022-23. Real GDP growth at 9.6 per cent remained robust during H1:2022-23 with a sharp acceleration in momentum from Q1 to Q2:2022-23. In Q3:2022-23, however, the momentum moderated (Chart II.2.1 and Appendix Table 2). II.2.4 Underlying the vicissitudes in aggregate demand conditions in 2022-23, were the compositional shifts among its major constituents (Chart II.2.2). Private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) registered a steady growth of 7.3 per cent, buoyed by an uptick in the contact-intensive activity including travel and tourism and an upbeat festival time demand in 2022-23. Government final consumption expenditure (GFCE) growth at 1.2 per cent remained muted as the government continued on a consolidation path to restore fiscal health while stepping up capital expenditure to support growth and investment. The improvement in the quality of expenditure bodes well for sustainability and de-risking of growth going forward. Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) remained strong with a double-digit growth of 11.2 per cent in 2022-23, primarily aided by the government’s thrust on infrastructure. As a result, the ratio of real GFCF to GDP increased to 34.0 per cent in 2022-23 from 32.7 per cent in the preceding year. India’s exports, after exhibiting remarkable recovery post-COVID with a growth of 29.3 per cent in 2021-22, tapered to 11.5 per cent in 2022-23. As the growth in imports at 18.8 per cent outpaced the growth in exports, the drag from net exports further widened to 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2022-23 from 1.3 per cent in the preceding year.

| Table II.2.1. Real GDP Growth | | Component | Growth (per cent) | | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | | I. Total Consumption Expenditure | 7.0 | 5.0 | -4.6 | 10.5 | 6.4 | | Private | 7.1 | 5.2 | -5.2 | 11.2 | 7.3 | | Government | 6.7 | 3.9 | -0.9 | 6.6 | 1.2 | | II. Gross Capital Formation | 6.2 | -6.0 | -11.6 | 22.2 | 9.6 | | Gross Fixed Capital Formation | 11.2 | 1.1 | -7.3 | 14.6 | 11.2 | | Change in Stocks | 27.3 | -58.7 | -85.5 | 687.8 | 1.9 | | Valuables | -9.7 | -14.2 | 26.4 | 34.0 | -14.8 | | III. Net Exports | | | | | | | Exports | 11.9 | -3.4 | -9.1 | 29.3 | 11.5 | | Imports | 8.8 | -0.8 | -13.7 | 21.8 | 18.8 | | IV. GDP | 6.5 | 3.9 | -5.8 | 9.1 | 7.0 | | Source: NSO. |

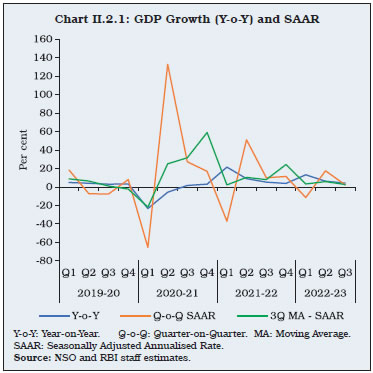

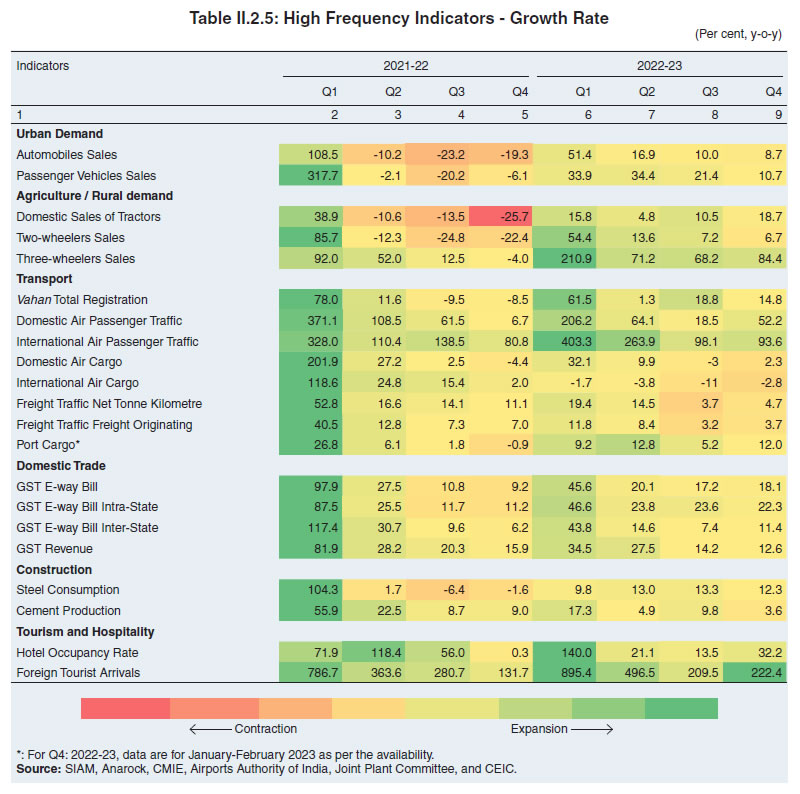

Consumption II.2.5 Emancipated from the COVID-19 induced restrictions which lingered for the previous two years, PFCE - the mainstay of aggregate demand - rebounded strongly to 13.2 per cent in 2022-23 above the pre-pandemic level. A well-rounded resumption in contact-intensive activity and pent-up demand in discretionary consumption spearheaded private consumption in the first half of the year. A resilient farm sector and an improvement in labour market conditions relative to the pandemic period supported the revival in consumption. The production of both consumer durables and non-durables weakened substantially in recent months, indicating a slowdown in consumption as the pent-up demand gradually weakened in the second half of the year. II.2.6 Indicators of consumption demand suggest a broad-based revival in 2022-23. Indicators pertaining to transport, viz., domestic air passenger traffic, railway passenger traffic and passenger vehicle sales recorded sharp upticks on y-o-y basis pointing towards a resumption in travel, tourism and hospitality. The revenge tourism across domestic leisure destinations combined with wedding/holiday season propelled the hotel, tourism and hospitality sector to turn around strongly and recuperate the loss suffered during the COVID-19 pandemic. Major labour market indicators - all-India unemployment rate, worker population ratio (WPR) and labour force participation rate (LFPR) surpassed their respective pre-COVID levels in Q1:2022-23. Salaries and wages in the corporate sector have registered steady growth in 2022-23. All these factors bode well for propelling consumption demand further. As per the March 2023 round of the consumer confidence survey (CCS) of the Reserve Bank, while the current situation index (CSI) improved further on account of improved sentiments on general economic situation, employment and household income, the future expectation index (FEI) remained positive despite marginally lower optimism. Household’s spending was buoyant for both essential and non-essential items with an expectation of a rise in non-essential outlay over the next year. II.2.7 Rural demand, which was deeply scathed by the second wave of COVID-19 a year ago recovered, albeit at a slower pace, vis-à-vis urban demand. Real rural wage growth virtually stagnated in 2022-23 despite a visible uptick in economic activity. Although job demand under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) declined on a y-o-y basis, it still prevailed above the pre-pandemic level in 2022-23, indicating that the recovery, especially in the unorganised segment of the economy is not yet complete (Box II.2.1). Investment and Saving II.2.8 The rate of gross domestic investment in the Indian economy, measured by the ratio of gross capital formation (GCF) to GDP at current prices, surged to 31.4 per cent in 2021-22 from the COVID induced slump to 27.9 per cent in the preceding year. Although data on GCF are not yet available for 2022-23, movements in its constituents suggest an uptick primarily led by government spending on infrastructure. The strong pick up in credit growth in 2022-23 and upbeat investment sentiment reflected in the forward-looking surveys conducted by the Reserve Bank, in particular the industrial outlook survey (IOS), suggest that the investment cycle recovery is likely to continue (Box II.2.2). Box II.2.1

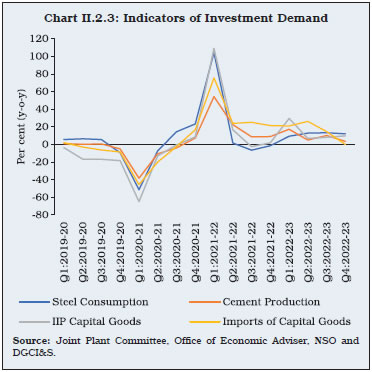

Unorganised Sector Recovery Post-Pandemic It has been widely conjectured that the economic loss on account of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to weigh heavily on unorganised sector activity. There is no official measure available on the nature of recovery of this segment of the economy post-pandemic. The very nature of operations of the unorganised or informal enterprises do not require maintenance of accounts or adherence to any regulations and hence, makes it difficult to have a proper account of unorganised sector activity in a timely manner. In the 2011-12 base year series, gross value added (GVA) generated within the household sector1 broadly captures the unorganised sector activity. The official estimates of the unorganised GVA are released on an annual basis with a lag of almost 10 months. Therefore, currently these data are available only up to 2021-22. Household sector GVA in real terms2 in 2021-22 is estimated to have increased by 3.1 per cent above the pre-pandemic level of 2019-20. The asymmetrical impact of the pandemic on the unorganised sector was corroborated by official data as well as survey-based studies and anecdotal evidence (Estupinan and Sharma, 2020). There was a sharp contraction even in nominal terms in the household GVA, while GVA of the organised sector registered marginal expansion in 2020-21. Within services, though both organised and household segments of hotels and restaurants; other services; transport; trade and repair; and construction registered a contraction, the contraction was more entrenched in the household segment. In an attempt to track the performance of the unorganised sector, a composite index for the unorganised sector activity at a monthly frequency is constituted adopting an indicator-based approach. The unorganised sector composite coincident index (UNCCI) with complete information set is available with a lag of 45 days since the end of a reference month. The high frequency indicators (HFIs) identified for the UNCCI broadly pertain to three categories in which the unorganised sector has a relatively larger presence – (i) agriculture; (ii) construction, trade and transport; and (iii) other miscellaneous activities. From a broader set of 15 indicators, the constituent indicators are selected based on their dynamic correlation with the benchmark indicator – household sector GVA growth. The UNCCIs have been developed using the dynamic factor model in the state-space framework (Geweke, 1977), which uses Kalman filter to derive the common trend from the constituent indicators. The UNCCI tracks the cataclysmic impact of COVID-19 and the subsequent recovery in the unorganised non-agriculture sector very well (Chart 1). The recent trajectory of the UNCCI points towards an uptick in November 2022 and showed further improvement in the subsequent months. The composite UNCCI stood robust at 6.9 per cent in March 2023. References: 1. Bhowmick, C., Goel, S., Das, S. and Gautam, (2022), ‘A Composite Coincident Index for Unorganised Sector Activity in India’, RBI Bulletin, December 2022. 2. Estupinan, Xavier and Sharma, Mohit, (2020), ‘Job and Wage Losses in Informal Sector due to the COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in India’, Rochester, New York. 3. Geweke, J. (1977), ‘The Dynamic Factor Analysis of Economic Time Series’ in Ainger, D.J. and Goldberger, A.S. (Eds), Latent Variables in Socio-Economic Models Pp 365-383, North-Holland Publications, Amsterdam. | II.2.9 Among the components of GFCF, activity in the construction sector is gathering traction owing to the focus of the government on infrastructure and the ebullient housing sector. This is evident from movement in its proximate coincident indicators – steel consumption and cement production (Chart II.2.3). Buoyant investment demand in machinery and equipment is evident from movements in their proximate coincident indicators – imports and production of capital goods – which have registered robust growth in 2022-23. Box II.2.2

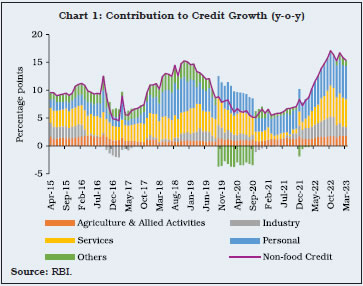

Role of Credit in Driving a Turnaround in Private Investment Cycle Bank credit plays an important role in financing the investments of corporates in India. A sustained increase in credit may have lead information about investment demand pick-up while an occasional rise may indicate demand for working capital which could be for utilisation of current capacity. As of March 2023, the non-food credit growth (year-on-year) was robust at 15.4 per cent, same as that of the nominal GDP for 2022-23. The broad-based expansion in bank credit has been facilitated by healthier balance sheets of banks (Chart 1). Despite the increase in commodity prices and rise in interest rates, corporate investments have picked up in the recent period. To assess as to whether the rise in bank credit could revive the investment cycle, the relationship between borrowings and fixed investments of listed non-financial firms is examined by a dynamic panel model for the period 2011-12 to 2020-21 (Arellano and Bond, 1991). Results show that a one percentage point higher growth in bank borrowings increases nominal net fixed assets (NFA) by around 0.17 percentage points (Table 1). Higher inflation raises operating costs, which in turn, may reduce fixed investment. The sensitivity of fixed investment to bank borrowings falls during periods of higher inflation. This highlights the crucial role of low and stable inflation to the investment outlook.

| Table 1: Bank Borrowing and Fixed Investment | | Explanatory Variables | ΔNFAit | ΔNFAit | ΔNFAit | ΔNFAit | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | | ΔNFAi,t-1 | 0.133*** | 0.859*** | 0.424** | 0.0862* | | (0.0316) | (0.108) | (0.192) | (0.0515) | | Bank Borrowing Growthit | 0.158** | 0.174*** | 0.201* | 0.0252 | | (0.0630) | (0.0662) | (0.104) | (0.125) | | R & D Expenditure Growthit | 0.121*** | 0.0440 | 0.115* | 0.0474 | | (0.0436) | (0.0450) | (0.0683) | (0.0600) | | Operating Expenses Growthit | -0.258*** | | | -0.328** | | (0.0837) | | | (0.146) | | Inflationt | | -0.535** | 1.027*** | | | | (0.210) | (0.323) | | | Bank Borrowing Growthit X Inflationt | | | -0.0504*** | | | | | (0.0116) | | | Bank Borrowing Growthit X Operating Expenses Growthit | | | | 0.0231 | | | | | (0.0184) | | Constant | 6.315*** | 1.588 | -0.317 | 7.885*** | | (0.769) | (2.078) | (2.474) | (1.664) | | N | 117 | 117 | 117 | 117 | | AR(1), p-value | 0.0229 | 0.00760 | 0.00890 | 0.0232 | | AR(2), p-value | 0.264 | 0.180 | 0.133 | 0.243 | | Hansen Test, p-value | 0.920 | 0.804 | 0.999 | 0.853 | ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1 per cent, 5 per cent and 10 per cent level, respectively.

Note: Figures in the parentheses are standard errors. In the above table ‘i’ stands for sector and ‘t’ for time.

Source: RBI staff estimates. | To reconfirm the nature of revival in investment activity, investment cycles are estimated by employing an asymmetric band-pass filter on quarterly seasonally adjusted investment rate and real gross fixed capital formation data. Cycles extracted from both series corroborate cyclical revival in investment from the slump encountered during the first wave of the pandemic (Chart 2). The sustainability of the revival going ahead is contingent on lower and stable inflation in India, stronger growth in global output and trade, improvement in financial conditions, timely project completion by the corporates and a favourable commodity price outlook. Reference: Arellano, M., and Bond, S. (1991), ‘Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations’, The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. | II.2.10 As per the order books, inventories and capacity utilisation survey (OBICUS) of the Reserve Bank, aggregate capacity utilisation (CU) of the manufacturing sector increased to 74.3 per cent in Q3:2022-23 from 74.0 per cent recorded in the previous quarter. The seasonally adjusted CU, however, declined by 40 bps and stood at 74.1 per cent in Q3:2022-23. For the manufacturing firms, new orders during Q3:2022-23 grew on a year-on-year basis. In Q3:2022-23, the ratio of both finished goods inventory (FGI) to sales and raw material inventory (RMI) to sales remained flat, reflecting a subdued demand condition. For Q4:2022-23, respondents of the IOS exhibited optimism, particularly regarding financial situation.  II.2.11 The rate of gross domestic saving as per cent to gross national disposable income (GNDI) surged to 30.0 per cent in 2021-22 from 28.4 per cent in the preceding year, led by lower dissaving of the general government sector, which offset the drop in household saving. The net financial saving of the household sector – the most important source of funds for the two deficit sectors, namely, the general government sector and the non-financial corporations – moderated to 7.6 per cent of GNDI in 2021-22, (Table II.2.2 and Appendix Table 3). The moderation in household financial saving in India is reflective of the release of pent-up demand, and the associated drawdown in precautionary saving as concerns relating to income flows subsided in 2021-22. | Table II.2.2: Financial Saving of Household Sector | | (Per cent of GNDI) | | Item | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | | A. Gross Financial Saving | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 15.2 | 11.0 | | of which: | | | | | | | | | | | | | 1. Currency | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | -2.1 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.1 | | 2. Deposits | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 3.5 | | 3. Shares and Debentures | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | | 4. Claims on Government | -0.2 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | | 5. Insurance Funds | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 1.9 | | 6. Provident and Pension Funds | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | | B. Financial Liabilities | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.4 | | C. Net Financial Saving (A-B) | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 11.3 | 7.6 | GNDI: Gross National Disposable Income.

Note: Figures may not add up to total due to rounding off.

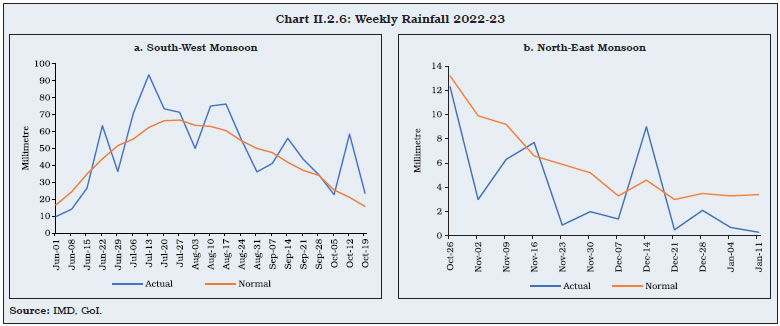

Source: NSO. | II.2.12 The resource gap of private non-financial corporations widened in 2021-22 due to a revival in investment demand (Chart II.2.4). The dissaving by the general government sector reduced from an elevated level owing to the government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation after the COVID induced increase in fiscal deficit in 2020-21. 3. Aggregate Supply II.2.13 Aggregate supply, measured by gross value added (GVA) at basic prices, expanded by 6.6 per cent in 2022-23, as compared with a growth of 8.8 per cent a year ago. With gradual revival in economic activity, the three-quarter moving average of seasonally adjusted annualised growth rate (MA-SAAR) exhibited an upturn in Q2:2022-23, but moderated in Q3:2022-23 (Chart II.2.5). II.2.14 GVA growth was driven by a resilient agriculture sector and broad-based recovery in the services sector (Table II.2.3). On the other hand, the industrial sector decelerated sharply amidst intensification of input cost pressures, supply chain disruptions and fledgling global demand conditions. Agriculture and Allied Activities II.2.15 Agriculture and allied sector growth moderated marginally in 2022-23, for the third consecutive year. The GVA of the sector grew by 3.3 per cent during 2022-23 on record production of foodgrains (including rice, wheat, maize, barley and pulses), sugarcane and rapeseed and mustard. The sector’s buoyancy during the year was generally supported by normal cumulative south-west monsoon (SWM) rainfall - despite its uneven distribution over time and across regions, and delayed withdrawal - and normal north-east monsoon rains. Deficient winter season rainfall (January-February) and the consequent above-normal temperature observed during February 2023 - the crucial month when flowering and grain-filling occurs in wheat and other rabi crops as well as in horticulture crops - posed downside risks to rabi production. Moreover, the unusual showers accompanied with the hailstorms during the month of March caused further risk to the rabi crops and delayed the harvesting of the crops in major producing states. II.2.16 The uneven temporal and spatial distribution of the SWM adversely impacted the progress of kharif sowing, reducing the area under cropping. Though the monsoon landed on the Indian mainland on May 29, 2022 (two days prior to its normal date) in line with the India Meteorological Department (IMD)’s forecast, rainfall remained less than normal in June 2022, delaying the onset of kharif sowing. Rainfall fluctuated from July 2022 through September 2022 (Chart II.2.6). However, cumulative rainfall at the end of the season (September 30, 2022) was normal at 6 per cent above the long period average (LPA). Spatially, while rains in north-west India hovered around the normal benchmark, central India and south peninsula received episodes of excessive rains during the middle as well as the end of the season, exposing some of the standing crops to damage. The east and north-east regions, which contribute more than one-third of India’s rice production, witnessed deficit rainfall during most of July to August 2022, the crucial months of kharif sowing. Notably, states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and West Bengal faced a deficit of more than 20 per cent as compared to their respective normal levels of rainfall. The final kharif acreage as at end-September 2022 was lower by 0.8 per cent as compared with the previous year. | Table II.2.3: Real GVA Growth | | (Per cent) | | Sector | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | | I. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 2.1 | 6.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.3 | | II. Industry | 4.9 | -2.5 | 0.9 | 10.5 | 1.7 | | II.1 Mining and Quarrying | -0.8 | -3.0 | -8.6 | 7.1 | 3.4 | | II.2 Manufacturing | 5.4 | -3.0 | 2.9 | 11.1 | 0.6 | | II.3 Electricity, Gas, Water Supply and Other Utility Services | 7.9 | 2.3 | -4.3 | 9.9 | 9.2 | | III. Services | 7.1 | 5.8 | -7.9 | 9.6 | 9.3 | | III.1 Construction | 6.5 | 1.6 | -5.7 | 14.8 | 9.1 | | III.2 Trade, Hotels, Transport, Communication and Services Related to Broadcasting | 7.2 | 6.0 | -19.7 | 13.8 | 14.2 | | III.3 Financial, Real Estate and Professional Services | 7.0 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 6.9 | | III.4 Public Administration, Defence and Other Services | 7.5 | 6.6 | -7.6 | 9.7 | 7.1 | | IV. GVA at Basic Prices | 5.8 | 3.9 | -4.2 | 8.8 | 6.6 | | Source: NSO. |

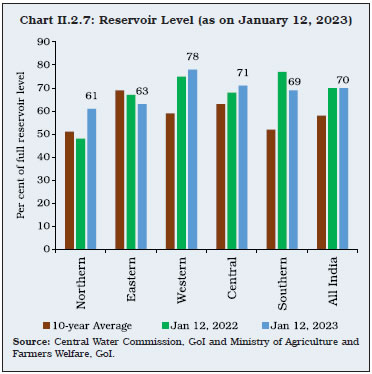

II.2.17 The withdrawal of SWM started around September 20, 2022 and ended on October 23, 2022. The slow withdrawal was due to cyclonic disturbances in the Bay of Bengal. As a result, most of the sub-divisions received heavy rains during September and October 2022. These rains ensured congenial soil moisture content as well as sufficient reservoir levels, which augurs well for the rabi season crops. The reservoir water storage level stood at 70 per cent of the full reservoir capacity as on January 12, 2023 (end of north-east monsoon) which was at par with the previous year’s level and 20 per cent higher than the last 10-year average (Chart II.2.7). Aided by these factors, the rabi crop sowing season 2022-23 ended with a record acreage of 720.7 lakh hectares, surpassing the last year’s sowing by 3.3 per cent. The jump in rabi crops acreage was mainly driven by wheat, rice, maize, lentil, rapeseed and mustard. Consequently, total foodgrains production in 2022-23 is estimated at 3,305.3 lakh tonne, as per the third advance estimates (3rd AE), 4.7 per cent higher than the final estimates (FE) for 2021-22 (Table II.2.4). The record foodgrains production for the seventh consecutive year is mainly contributed by rabi crops (9.5 per cent y-o-y growth) as production of kharif crops contracted marginally [(-)0.2 per cent]. As regards the horticulture production, the third advance estimates (3rd AE) for 2021-22 revised the overall production upward by 7.0 lakh tonne to 3,423.3 lakh tonne, 2.3 per cent higher than that of 2020-21, driven by an increase in production of both fruits and vegetables.

| Table II.2.4: Agricultural Production 2022-23 | | (Lakh tonne) | | Crop | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2022-23 (3rd AE) Variations (Per cent) | | 3rd AE | Final | Target | 3rd AE | Over 2021-22 | Over 2022-23 | | 3rd AE | FE | Target | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | | Foodgrains | 3,145.1 | 3,156.2 | 3,280.0 | 3,305.3 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 0.8 | | Kharif | 1,549.3 | 1,553.6 | 1,631.5 | 1,551.2 | 0.1 | -0.2 | -4.9 | | Rabi* | 1,595.9 | 1,602.5 | 1,648.5 | 1,754.2 | 9.9 | 9.5 | 6.4 | | Rice | 1,296.6 | 1,294.7 | 1,305.0 | 1,355.4 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 3.9 | | Wheat | 1,064.1 | 1,077.4 | 1,120.0 | 1,127.4 | 6.0 | 4.6 | 0.7 | | Pulses | 277.5 | 273.0 | 295.5 | 275.0 | -0.9 | 0.7 | -6.9 | | Oilseeds | 385.0 | 379.6 | 413.5 | 410.0 | 6.5 | 8.0 | -0.8 | | Sugarcane | 4,305.0 | 4,394.3 | 4,150.0 | 4,942.3 | 14.8 | 12.5 | 19.1 | | Cotton # | 315.4 | 311.2 | 370.0 | 343.5 | 8.9 | 10.4 | -7.2 | | Jute & Mesta ## | 102.2 | 101.5 | 105.0 | 94.9 | -7.1 | -6.5 | -9.6 | *: Including summer crops production. #: Lakh bales of 170 kg each. ##: Lakh bales of 180 kg each.

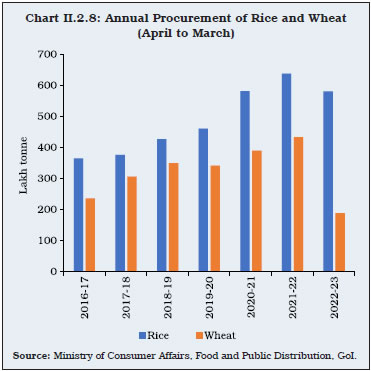

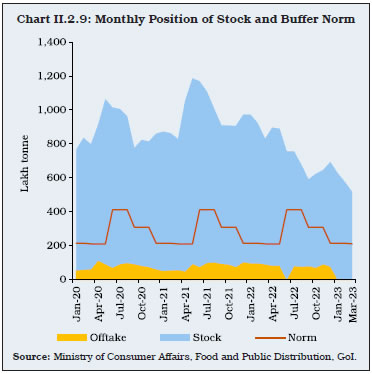

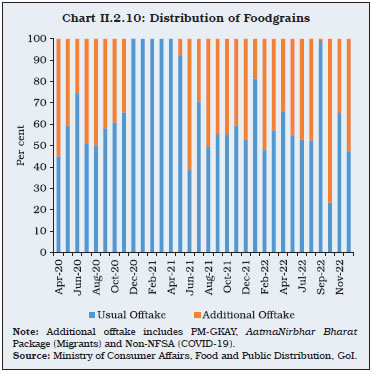

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, GoI. | II.2.18 In line with the approach adopted in recent years, the minimum support prices (MSPs) announced in 2022-23 for both rabi and kharif crops ensured a minimum return of 50 per cent over the cost of production3. The prices increased in the range of 2.0 per cent (for gram) to 9.1 per cent (for lentils) across crops. As on March 31, 2023, the procurement of rice was 492.2 lakh tonne during the kharif marketing season of 2022-23, which is 2.2 per cent lower than the corresponding period of last year (Chart II.2.8). As a result, the buffer stocks of rice stood at 3.2 times the buffer norm as on March 31, 2023 (Chart II.2.9).

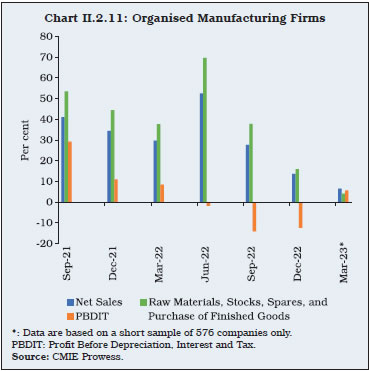

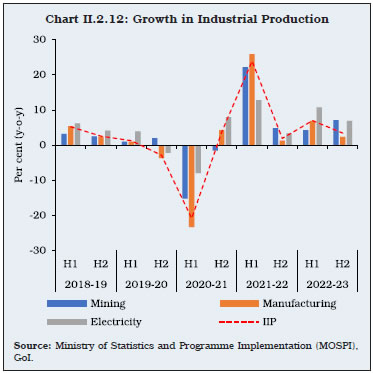

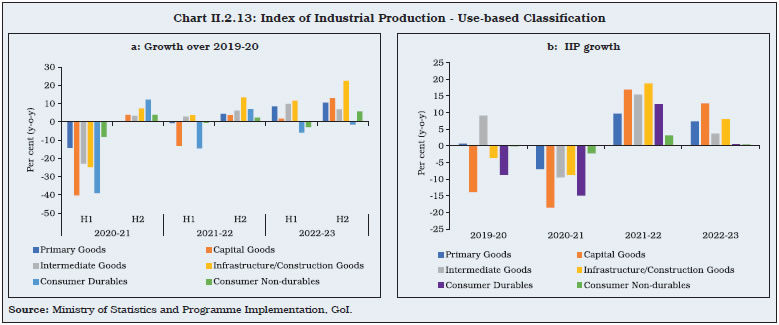

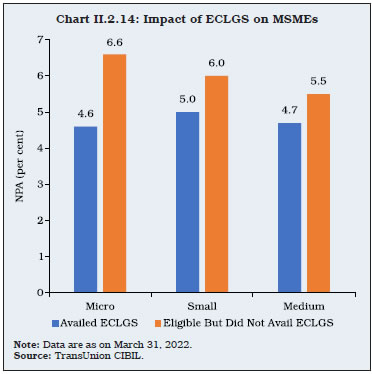

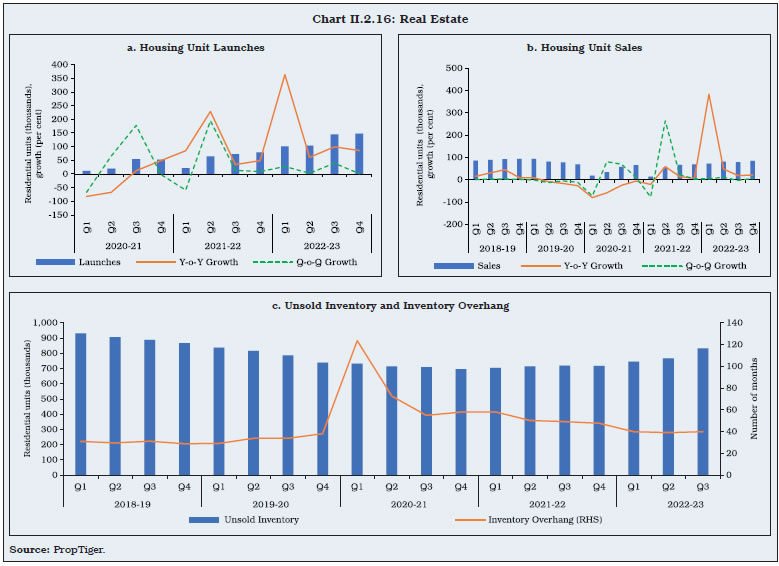

II.2.19 Wheat stocks were 1.1 times the buffer norms (as on March 31, 2023) due to a y-o-y decline of 56.6 per cent in its procurement in the rabi marketing season of 2022-23. The lower procurement of wheat was mainly on account of yield loss due to persistent heatwaves during the harvesting months of March and April 2022; and the rise in wheat exports after the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war. The Government of India imposed restrictions on exports of wheat (on May 14, 2022), wheat-based products (on August 25, 2022) and broken rice as well as higher export duties on non-basmati rice except for parboiled rice to ensure domestic availability. In the months of February and March 2023, the government also offloaded 3.4 million tonne of wheat from the central pool stock to the market through e-auctions under the open market sale scheme (domestic) to curb inflationary pressures from wheat. II.2.20 To offset the declining stocks of wheat, the distribution of wheat under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PM-GKAY) was substituted with rice in the sixth and seventh phases of the scheme during April-December 2022. Since its inception in April 2020, the distribution of foodgrains under the scheme accounted for a significant share in the total offtake under the public distribution system (PDS) [Chart II.2.10]. With the pandemic ebbing, the foodgrains distribution under PM-GKAY was discontinued from January 1, 2023. Instead, the Union Government announced Integrated PM-GKAY scheme that made provision that the foodgrains (rice, wheat and coarse grains) provided under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), which included 5 kg. per person per month to the priority households’ beneficiaries and 35 kg. per household per month to the Antyodaya Anna Yojana beneficiaries to about 81.35 crore beneficiaries, at subsidised prices (₹3/2/1 per kg. of rice/wheat/coarse grains, respectively), would be given free of charge in 2023.  Industrial Sector II.2.21 During 2022-23, the industrial sector’s growth moderated amidst lingering global uncertainties. The organised manufacturing sector which benefitted from the lower base as well as softer raw material costs during 2021-22 faced the brunt of rising raw material costs in H1:2022-23 (Chart II.2.11). The supply chain bottlenecks following the war in Ukraine coupled with elevated raw material costs, impacted the profitability of manufacturing companies. While increased sales in Q1:2022-23 cushioned the hike in raw material costs, the global slowdown impacted sales in Q2:2022-23 adversely, resulting in profit diminishing at an accelerated pace. In Q3:2022-23, a moderation in input costs could only contain the decline in profits to some extent.  II.2.22 Industrial output measured by the index of industrial production (IIP) expanded by 5.1 per cent during 2022-23 as compared to 11.4 per cent last year. Manufacturing sector, which accounts for three-fourths of the industrial sector largely shaped the industrial sector recovery (Chart II.2.12). Within the manufacturing sector, 19 out of 23 industry groups recorded expansion in H1:2022-23, fuelled by manufacturing of motor vehicles, coke and refined petroleum products, basic metals, chemical products, and machinery and equipment. Manufacturing activity moderated to 2.4 per cent in H2:2022-23, affected by a slowdown in global demand. Labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, wearing apparel, leather and related products, computer, electronic and optical products, and electrical equipment recorded contraction in H2:2022-23, while basic metals, motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers, machinery and equipment, and other non-metallic mineral products recorded expansion. The automobile sector, which was riddled by supply chain bottlenecks, bounced back during 2022-23 supported by festive season sales.  II.2.23 In terms of use-based classification in H1:2022-23, all categories recorded y-o-y expansion barring consumer non-durables, while in H2:2022-23, only consumer durables registered a decline. In 2022-23, primary goods, and infrastructure/construction goods recorded robust growth on a y-o-y basis as well as over the pre-pandemic year 2019-20. While capital goods supported a rise in economic activity, production of consumer goods remained sluggish, with production of consumer durables remaining below the pre-pandemic output levels of 2019-20 and consumer non-durables remained flat during 2022-23 (Chart II.2.13).  II.2.24 The micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) segment, which contributes about 29 per cent of India’s GDP and employs over 11 crore workers, recorded a modest recovery. The revenue for the MSME sector is projected to exceed the pre-COVID level in 2022-23 by 25 per cent.4 With 99.8 per cent of MSMEs being unregistered, they account for a sizeable share of the unorganised sector output and employment [National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), 2015-16]. Various policy measures were introduced to support the sector from the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS), which aimed at meeting their liquidity needs for sustaining business operations. As per the assessment of the Credit Information Bureau (India) Limited (CIBIL), the scheme assisted MSME borrowers in managing their businesses better with lower non-performing assets (NPAs) for borrowers availing the facility as compared to borrowers who were eligible but did not avail of it (across all categories of micro, small and medium industries) [Chart II.2.14].  II.2.25 The mining sector output recorded 4.3 per cent y-o-y growth in H1:2022-23, mainly on account of a double-digit growth in coal production, that became necessary to compensate for the reduced imports in response to high international prices. In H2:2022-23 mining sector remained robust with 7.1 per cent y-o-y growth, coal continued to register strong growth, while crude oil recorded a contraction in H2:2022-23. Electricity generation expanded at 10.8 per cent during H1:2022-23 led by strong growth in thermal and renewable energy but moderated to 6.9 per cent in H2:2022-23. Renewable energy, which accounts for 12.6 per cent of the overall generation, recorded a robust 21.3 per cent growth during H2:2022-23 from that of 17.3 per cent during H1:2022-23. While India missed the renewable energy capacity target of 175 gigawatt (GW) by 2022, the progress made so far is commendable as the installed capacity of renewable energy (excluding hydro), increased by 81.3 per cent between 2017-18 and 2022-23 making the share of renewables5 (excluding hydro) in total installed capacity rise to 30.1 per cent in March 2023. The share of renewable sources in total power generation has also been rising consistently from 7.2 per cent in the quarter-ended September 2015 to 12.6 per cent in the quarter-ended March 2023 (Chart II.2.15). II.2.26 The outstanding overdues of the electricity distribution companies (DISCOMs) owed to electricity generation companies (GENCOs) is a major issue plaguing the power sector in India. To address this, the government had introduced the late payment surcharge (LPS) scheme in May 2022, under which all dues to power generator till June 3, 2022 are being liquidated in up to 48 instalments. Accordingly, the total outstanding dues by DISCOMS came down considerably to ₹58,231 crore as on March 1, 2023 from ₹1,00,018 crore on May 18, 2022. Services Sector II.2.27 Services sector, which being contact-intensive faced the major brunt of COVID-19 pandemic, revived strongly in 2022-23. The high frequency indicators of services sector indicated strong growth in Q1:2022-23 supported by low base, but the momentum moderated in Q2 and Q3. In Q4:2022-23, three-wheeler sales, air passenger traffic and GST E-way bills improved while sales of passenger vehicles and construction sector moderated. Among sectors, construction, domestic trade and transport surpassed their pre-pandemic levels, while aviation, tourism and hospitality sectors, though recovering, are yet to reach the respective pre-pandemic levels (Table II.2.5).  II.2.28 The construction sector remained upbeat due to sustained impetus on infrastructure spending by the government. After a robust performance in the pandemic afflicted years, the information technology sector moderated in 2022-23, with companies recording a decline in profits due to a slowing global economy. The hospitality sector bounced back in 2022-23 as demand for leisure and corporate travel boosted activity. In the financial sector, aggregate deposits and bank credit to the commercial sector recorded expansion. Public administration, defence and other services (PADO) remained resilient in 2022-23 primarily on account of a sharp pick up in other services while government expenditure – especially that of the central government remained muted during the year. II.2.29 Pent-up demand and robust consumer sentiment for home ownership in the aftermath of the pandemic underlay strong recovery in the residential housing sector in 2022-23. In 2022-23, housing launches improved consistently in terms of completed projects after two years of intermittent shutdowns. Housing sales picked up in H1:2022-23 and recovered in Q4 after briefly losing momentum in the third quarter. As launches surpassed sales, unsold inventory increased (Chart II.2.16).  II.2.30 The pandemic boosted digitalisation across sectors. The digital adoption helped sustain economic activity by facilitating quick re-orientation of business operations. Indian technology companies, consisting of 1,08,585 companies, with 30,887 companies having a total funding of US$ 181 billion, as on March 3, 2023, overarchingly rely on the internet ecosystem for their core business activities. India also has the third largest start-up ecosystem in the world with government recognised start-ups rising to 26,542 in 2022 (Chart II.2.17). II.2.31 Aviation passenger traffic performed better than cargo traffic in H1:2022-23 and H2: 2022-23, although it remained below pre-pandemic levels. Port cargo remained firm in H1:2022-23 but moderated in subsequent quarters as international trade decelerated. GST E-way bills, GST revenues and railway freight collection exhibited buoyant momentum in 2022-23 (Table II.2.5). II.2.32 The Reserve Bank’s services sector composite index (SSCI)6, which tracks activity in construction, trade, transport and financial services and is a coincident indicator of GVA growth in the services sector excluding PADO, witnessed a further uptick in Q4:2022-23 (Chart II.2.18). 4. Employment II.2.33 The labour market indicators from the annual periodic labour force survey (PLFS) suggest a declining trend in the unemployment rate amid rising labour force participation rate during 2021-22 (Chart II.2.19). II.2.34 As per the quarterly PLFS, the labour market conditions in urban areas have shown consistent improvement during 2022-23. Labour force participation during Q3:2022-23 surpassed the pre-pandemic January-March 2020 level. Worker to population ratio peaked during October-December 2022 and the unemployment rate stood at its lowest since the start of the survey in 2017-18 (Chart II.2.20).

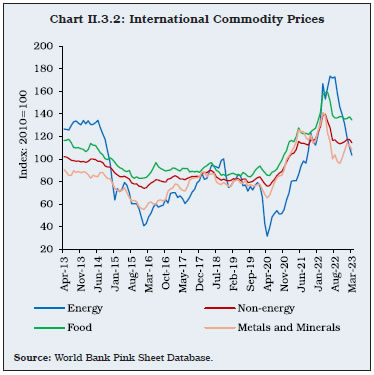

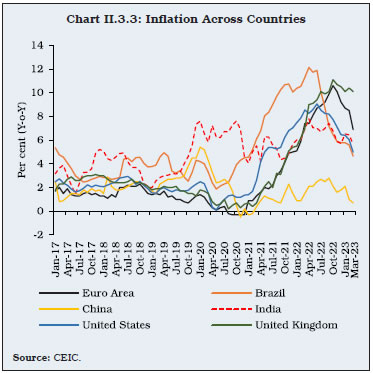

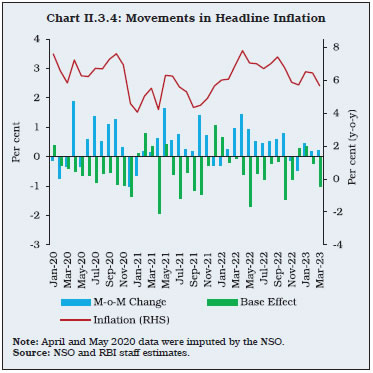

II.2.35 Organised sector employment, as measured by payroll data, indicated recovery in job creation in 2022-23. The average net subscribers added to Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) per month increased to 11.5 lakh in 2022-23 from 10.2 lakh in 2021-22, signalling an improvement in formal employment opportunities. II.2.36 The various alternate employment indicators also showed steady improvement in employment conditions during 2022-23. The purchasing managers’ index (PMI) for employment showed continued uptick in payroll hiring in both manufacturing and services sector. The employment index remained above ‘no change’ level of 50 for the manufacturing sector all through 2022-23 except for a marginal contraction in March 2023, while for services, it was positive for the entire period except for a marginal decline in May 2022. Similarly, the Naukri index which provides information on hiring activity based on the job listings on Naukri.com has also showed improvement in employment conditions during 2022-23 (Chart II.2.21). 5. Conclusion II.2.37 India exhibited robust growth in 2022-23 amidst prevailing global headwinds. Sound domestic macro-fundamentals, fiscal policy thrust on capex, healthy balance sheets of the corporate sector and the financial sector, and structural reforms announced and implemented over the recent years by the government have strengthened resilience of the economy, besides stepping up the growth momentum. Subdued external demand conditions operated as a drag. Labour market conditions normalised, and unorganised sector activity returned to expansion zone in 2022-23. The universal vaccination programme of the government - one of the largest mass vaccination drives in the world, involving more than two billion doses - helped in improving consumer and business confidence. II.3 PRICE SITUATION II.3.1 Inflation surged across advanced economies (AEs) and emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) to multi-decadal highs in 2022, primarily driven by the soaring food and energy prices amidst renewed supply disruptions following the war in Ukraine, tighter labour market conditions in AEs, firming up of growth momentum from pandemic time lows and volatility of financial markets in EMDEs resulting from spillovers from the aggressive tightening of monetary policy by the US Fed. Globalisation of inflation, and the realisation that the price pressures are not transitory, led to synchronised tightening of monetary policy, with an emphasis on front-loading to ensure a soft landing. II.3.2 Global commodity prices soared during the first half of 2022, driven by lingering post-COVID supply constraints, which got exacerbated by the war in Ukraine leading to global shortages in key food, energy and other commodities. The World Bank energy price index increased by 54.4 per cent over December 2021 to reach a peak in June 2022, while food prices increased by 24.9 per cent to reach a peak in May 2022 and metals and minerals by 21 per cent to a peak in March 2022. Subsequently, however, commodity prices underwent sharp corrections with the energy price index falling by 40.4 per cent in March 2023 over June 2022 levels. Similarly, food prices declined by 15.3 per cent and metals and minerals by 23.3 per cent from their respective peaks. Notwithstanding notable decline in global commodity prices in the later part of 2022 and early 2023, heightened geopolitical uncertainty, financial market volatility, re-emergence of another COVID-19 wave in some countries and the associated supply chain disruptions sustained the price pressures, limiting the pace of disinflation despite significant tightening of monetary policy. II.3.3 In India, headline inflation7 remained above the upper tolerance level of the inflation target over the successive months during January-October 2022. After a short-lived moderation in November and December 2022, driven by seasonal easing in food prices, inflation increased again in January-February 2023 before moderating in March 2023. Inflation reached a peak in April 2022 at 7.8 per cent driven by a sharp increase in inflation in all the three major groups - food, fuel and core (i.e., excluding food and fuel) inflation - on continued supply disruptions, rise in global commodity prices and currency depreciation, the common adverse global shocks for EMDEs associated with the war in Ukraine (Chart II.3.1). Subsequently, normalisation of supply chain pressures, easing of input cost pressures led by decline in global commodity prices, proactive supply management measures by the government and judicious monetary policy actions by the Reserve Bank softened the price pressures, bringing inflation to below the upper tolerance level in November and December 2022, before it surged again in January-February 2023 due to larger than expected price build-up in cereals. Core inflation generally remained elevated and sticky during the year, reflecting gradual pass-through of input cost pressures to goods inflation and subtle uptick in services inflation.

| Table II.3.1: CPI Headline Inflation – Key Summary Statistics | | (Per cent) | | Item | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | | Mean | 9.4 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 6.7 | | Standard deviation | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | | Skewness | -0.2 | -0.1 | -0.9 | 0.2 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | -0.7 | -0.1 | -0.1 | | Kurtosis | -0.5 | -1.0 | -0.1 | -1.6 | -1.0 | -1.5 | -1.4 | -0.7 | -1.0 | -0.6 | | Median | 9.5 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 6.7 | | Maximum | 11.5 | 7.9 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 7.8 | | Minimum | 7.3 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 5.7 | Note: Skewness and Kurtosis are unit-free. Annual inflation is the average of the monthly inflation rates during the year and therefore, may vary from the annual inflation calculated from the average index for the year.

Source: NSO and RBI staff estimates. | II.3.4 Average inflation in 2022-23 increased sharply from its level in 2021-22, while volatility in inflation, as measured by the standard deviation of the consumer price index (CPI) inflation, was marginally lower than a year ago (Table II.3.1). Further, the intra-year distribution of inflation showed a negative skewness reflecting higher than the average inflation prints in many months. II.3.5 Against this backdrop, sub-section 2 assesses developments in global commodity prices and inflation. Sub-section 3 discusses movements in headline inflation in India including major turning points, followed by a detailed analysis of its primary constituents in sub-section 4. Other indicators of prices and costs are analysed in sub-section 5, followed by concluding observations. 2. Global Inflation Developments II.3.6 The spike in commodity prices in Q1:2022-23 was primarily led by energy, food and fertiliser, following the war in Ukraine and recovering global demand (Chart II.3.2). Global crude oil prices rose sharply in Q1:2022-23, reaching a peak of US$ 117 per barrel in June 2022. Notwithstanding the decision by the organisation of the petroleum exporting countries (OPEC) and their allies (OPEC+) to reduce their production target by 2 million barrels per day in October 2022, easing of supply constraints and synchronised tightening of monetary policy that posed the risk of a global recession led to a sharp correction in crude oil prices to US$ 76.5 per barrel in March 2023 (i.e., a correction of 34.5 per cent from the June 2022 peak). Natural gas prices peaked in August 2022 reflecting the conflict induced supply constraints faced by Europe but eased significantly by March 2023 in response to a milder winter and energy conservation measures in the European Union (EU). Metal prices witnessed sharp decline beginning 2022-23 as global growth slowed and demand moderated. While international food prices moderated from the May 2022 peak with easing supply conditions in edible oils and grains, they remained above the pre-conflict level due to decline in production on adverse weather conditions in major producing countries and trade restrictions. Moreover, higher natural gas and coal prices affected fertiliser production, pushing up their prices and consequently the input costs for food crops. Reflecting these global commodity price developments, consumer price inflation surged in both AEs and EMDEs, warranting synchronised monetary policy tightening during the year (Chart II.3.3).  3. Inflation in India II.3.7 CPI headline inflation in India remained above the upper tolerance level of 6 per cent for 10 successive months since January 2022, before moderating during November-December on seasonal easing in food prices. Inflation picked up again in January-February 2023 before easing to 5.7 per cent in March 2023 (Chart II.3.4). The pick-up in headline inflation during the year was broad-based resulting from pass-through of higher global commodity prices (crude oil, metals and food prices) and adverse domestic weather conditions. After reaching a peak in April 2022 following the war in Ukraine, inflation eased with gradual improvement in global supply conditions, record domestic food production, targeted supply side measures undertaken by the government including excise duty cuts on petrol and diesel along with lower import duties and imposition of export restrictions on some inflation sensitive agricultural items. Cumulative tightening of policy repo rate by 250 basis points (bps) during May 2022-February 2023 also aided in containing price pressures in the second half of 2022-23 (Box II.3.1).

Box II.3.1

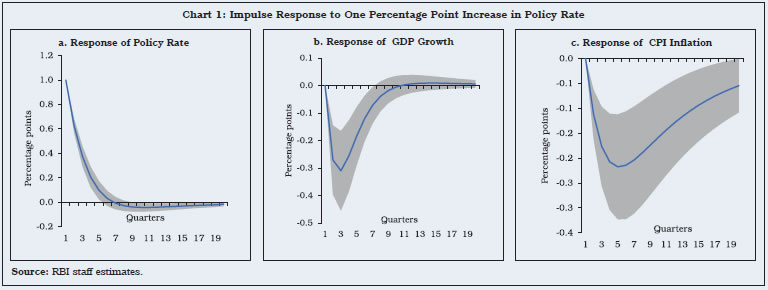

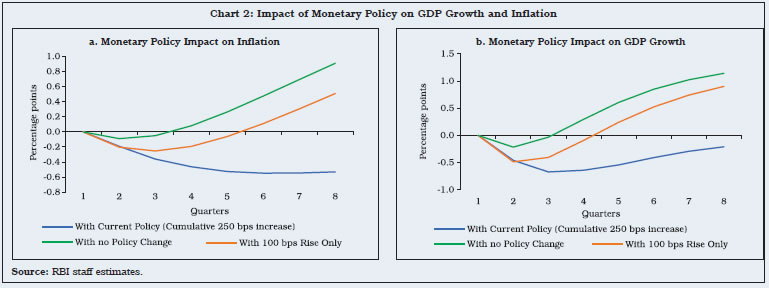

Monetary Policy and Disinflation To tame inflation and bring it within the tolerance band as the immediate priority, the Reserve Bank raised the policy repo rate cumulatively by 250 bps between May 2022 and February 2023 while shifting policy stance to withdrawal of accommodation. To assess the effectiveness of monetary tightening, a four variable VAR model is used with year-on-year (y-o-y) growth in real GDP, CPI (excluding food and fuel) inflation (y-o-y), gross fiscal deficit (GFD) of the central government as per cent of GDP and policy interest rate as the key variables. This is estimated for the period Q1:1998-99 to Q4:2021-22, controlling for the COVID-19 pandemic shock through a dummy variable. The impulse response results suggest a statistically significant response of growth and inflation to monetary policy shock (Chart 1). A one percentage point (pp) rise in the policy rate leads to a peak impact of 30 bps fall in GDP growth in the third quarter with the impact lasting up to the 8th quarter. The impact on inflation operates with a higher lag, with the peak impact of 22 bps materialising in the 5th quarter, and persisting for a longer time period, even beyond four years. Using the same VAR model, a policy response experiment is conducted to assess the importance of timely and front-loaded monetary policy actions, following Cho and Moreno (2006). The counterfactual exercise is undertaken with Q1:2022-23 as the starting point and assessing the impact up to eight quarters to account for monetary policy transmission lags under three scenarios: (a) no policy change or maintaining repo rate at 4 per cent for the whole period; (b) increase in policy repo rate by 100 bps only once in Q1:2022-23; and (c) a tightening of policy as under the current scenario, i.e., an increase in repo rate by 250 bps until February 2023. The simulation results from this exercise suggest that under the no policy change scenario, inflation would have remained above 6 per cent throughout, reaching a peak of 7.3 per cent by the end of 8th quarter (Chart 2). Under the second scenario, inflation would have been lower by about 25 bps as compared to the no policy change scenario. However, under the current tight monetary policy (scenario c), inflation is estimated to have eased by more than 50 bps as compared to a rise in inflation of about 90 bps under policy repo rate left unchanged at 4 per cent. The efforts to control inflation by maintaining current policy stance might have sacrificed growth by about 65 bps. The significance of front-loaded policy action is evident from the fact that inflation would have been higher by 90 bps without the cumulative increase in the repo rate by 250 bps, whereas with only one-off 100 bps increase in the repo rate, inflation would have been lower by only 25 bps.

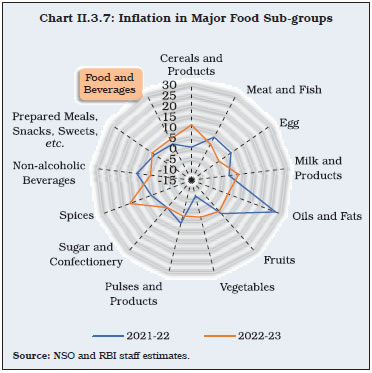

Reference: Cho, S., and Moreno, A. (2006), ‘A Small-sample Study of the New-Keynesian Macro Model, ‘Journal of Money, Credit and Banking’, Vol. 38, Issue 6, 1461-1481. | II.3.8 Inflation in food and beverages was the primary source of headline inflation build up, with its contribution to headline inflation increasing to 46.4 per cent in 2022-23 from 35.9 per cent in the previous year. Higher global food prices, supply shortages and adverse domestic weather conditions led to the pick-up in food prices, driven by cereals, vegetables, milk and spices. II.3.9 Inflation in fuel and light averaged at 10.3 per cent in 2022-23, driven by a sharp pick-up in prices of kerosene and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) which, in turn, reflected the impact of rise in global energy prices following the war in Ukraine. After remaining in deflation until October 2022, electricity prices recorded an inflation of 3.1 per cent in November 2022 due to unfavourable base effect and increase in tariffs in a few states. II.3.10 Inflation excluding food and fuel, or core inflation, remained persistently elevated at around 6 per cent during the year. The price pressures were broad-based, reflecting pass-through of input cost pressures and recovering domestic demand (Box II.3.2). A combination of factors - supply shocks, recovering demand, inflation expectations, exchange rate depreciation, fiscal stance - impacted the inflation trajectory (RBI, 2023)8. After a sharp pick-up in April 2022, however, price pressures moderated to some extent, aided by supply side measures by the government, including excise duty cuts in petrol and diesel effected on May 22, 2022. The main drivers of the ascent in core inflation were clothing and footwear, housing, transport and communication, health, household goods and services, and recreation and amusement. II.3.11 During 2022-23, headline inflation averaged 6.7 per cent, 115 bps higher than a year ago (Appendix Table 4). Box II.3.2

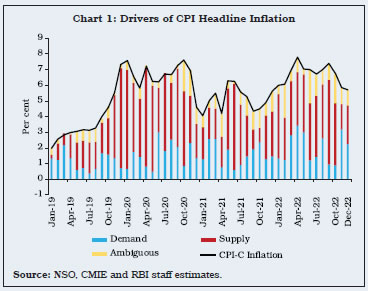

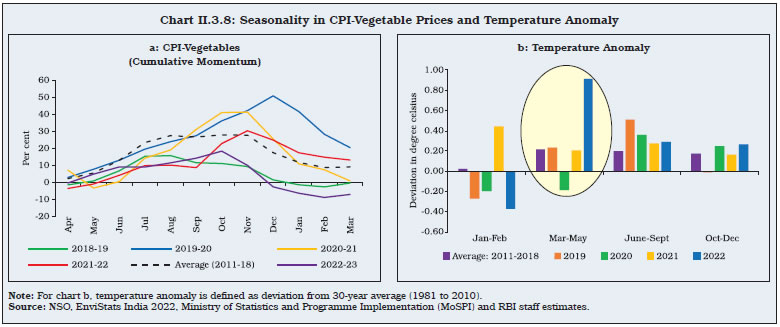

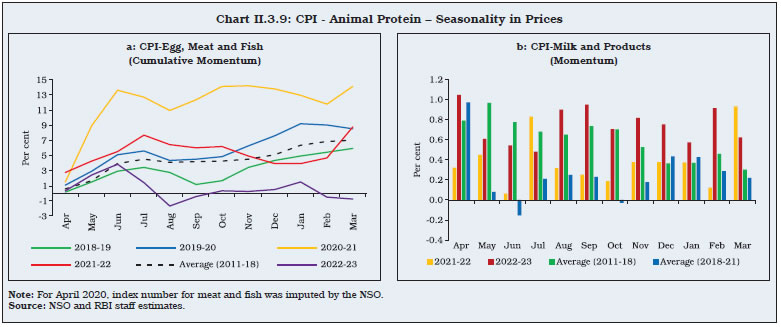

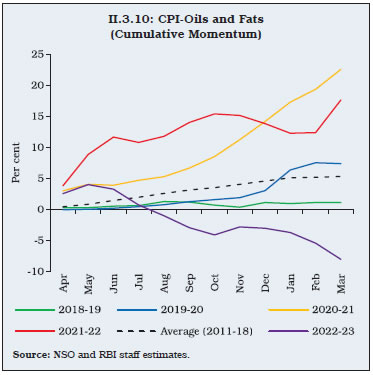

Recent Inflation Dynamics in India – Role of Supply vis-à-vis Demand Distinguishing between the role of demand and supply in driving inflation is critical to guide the conduct of monetary policy in managing the difficult growth-inflation trade-offs. As the persistence of supply shocks raise the risks of high inflation with suppressed economic growth (Shapiro, 2022a), it is imperative to understand the relative contribution of supply shocks driving inflation. In the literature, matching price and volume data from personal consumption expenditures (PCE) as in the case of the US (Shapiro, 2022a and 2022b) and quarterly national accounts data for household consumption expenditure (where matching price and volume data are not available) [OECD, 2022] have been used to distinguish between demand and supply shocks. This is done by identifying the direction of price and volume shocks for different items by running a bi-variate vector auto regressive (VAR) model on a rolling window and interpreting their residuals. Price and volume residuals with the same signs are assumed to reflect demand – higher demand pushes up both prices and volumes in the same direction and vice versa – while residuals with opposite signs correspond to supply shocks – lower supply means a reduction in volume with an increase in price. As matching prices and volume data are not available for the CPI items for India, the 23 CPI sub-groups data on prices are mapped to CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy) CPHS (Consumer Pyramid Expenditure Survey) consumption expenditure data.9 Next, the CMIE CPHS expenditure categories are deflated by the corresponding CPIs to derive a proxy for volume. To get a homogeneous base, these 23 mapped CPI sub-groups and corresponding CMIE CPHS expenditure categories are rebased to January 2014=100 and then de-seasonalised. The sample period for the analysis is January 2014 to December 2022 based on CMIE CPHS data. In line with OECD, 2022, a two-equation VAR model for prices and quantities is run for a 5-year rolling window as follows: The one-period ahead forecasts of both price and quantity are generated for each of the 23 matched categories and compared with their actual values. These 23 sub-groups are categorised each month during January 2019-December 2022 into demand, supply and ambiguous10 components, after which the CPI weights of these sub-groups are used to calculate their contributions to CPI inflation. These contributions to CPI inflation are then aggregated into demand driven, supply driven and ambiguous components to quantify the extent of demand and supply driven inflation. The results show that vegetables, milk, pulses, oils and fat, sugar, egg, and meat and fish within the food group experience frequent supply-side pressures, while non-alcoholic beverages, health, household goods and services and recreation and amusement are mainly impacted by demand side factors. Overall, the average contributions of demand side factors to inflation, which was 35.2 per cent in 2019, dropped during the COVID-19 shock to 24.6 per cent in 2020, and then recovered gradually to 31.8 per cent in 2021 and 30.5 per cent in 2022. During excess rain induced supply shocks in October-November 2019 as well as during different phases of COVID-19, supply side factors became predominant. On an average, supply side factors contributed around 55 per cent to CPI headline inflation during the entire sample period (Chart 1).  Post the war in Ukraine, besides the supply side factors, the role of demand side factors in driving inflation has also increased, reaching around 42.5 per cent during March-May 2022 and 54.2 per cent in November 2022 led by a pick-up in festive demand. This empirical finding supports timely introduction of monetary tightening phase in May 2022, and its continuation through the year with a cumulative increase in the policy repo rate by 250 basis points. Thus, sequencing of the Reserve Bank’s policy actions was appropriately timed to judiciously balance the growth-inflation trade-offs. References: 1. Shapiro, A. H. (2022a), ‘A Simple Framework to Monitor Inflation’, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2020-29. 2. Shapiro, A. H. (2022b), ‘How Much do Supply and Demand Drive Inflation?’, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, 15. 3. OECD (2022), ‘Supply- and Demand-driven Inflation in OECD Economies’, Economic Outlook, Vol. 2022, Issue 2. | 4. Constituents of CPI Inflation II.3.12 During 2022-23, CPI headline inflation was primarily driven by food and beverages, followed by fuel and light, clothing and footwear, health and education and transport and communication (Chart II.3.5). Food II.3.13 Inflation in food and beverages (weight: 45.9 per cent in CPI) hovered in a wide range of 4.6 per cent to 8.4 per cent in 2022-23 reflecting a combination of shocks - conflict induced global food and fertiliser price surge, adverse impact of heat wave on domestic rabi crop production and elevated farm input cost pressures - and seasonal price behaviour. Increase in the prices of vegetables, animal proteins, and cereals and products were the key drivers of hardening food inflation in the first half, while easing of vegetables and oils and fats prices drove the moderation in inflation in the second half (Chart II.3.6). II.3.14 Food and beverages inflation averaged 6.7 per cent in 2022-23 as compared with 4.2 per cent in 2021-22. Within the food group, inflation increased in five sub-groups while it moderated for the remaining seven sub-groups (Chart II.3.7). Prices of cereals, vegetables, milk, prepared meals, snacks, sweets, etc. and spices witnessed higher inflationary pressures during a major part of the year, driving up overall food inflation. II.3.15 Early onset of summer, heat waves and excess rains pushed up vegetable prices (weight: 13.2 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) in H1:2022-23 which ebbed with fresh crop arrivals in November 2022 (Chart II.3.8a and II.3.8b). As a result, after rising till October 2022, the cumulative momentum of vegetable prices moderated sharply in November and turned negative since December 2022, recording an average inflation of 3.0 per cent during the year 2022-23.  II.3.16 Onion prices moderated during April-May 2022 on account of robust rabi harvest [an increase of 17.4 per cent in 2021-22 as per the 3rd advance estimates (AE) over 2020-21 final estimates (FE)] and record procurement of 2.5 lakh tonne by the Centre for price stabilisation buffer for 2022-23 (higher by 0.5 lakh tonne compared to 2021-22). Price pressures, however, emerged in the subsequent months (barring September 2022) until November 2022 due to seasonal uptick in demand and loss of kharif output on account of both deficit and excess rainfall in key kharif onion-producing states. Tomato prices exhibited significant volatility in 2022-23 with a sharp summer pick-up during April-June 2022 followed by significant corrections in the next two months and another spell of increase during September-October 2022 owing to vagaries of monsoon. The volatility in the prices was driven by extreme weather events, including heat waves in north India, uneven distribution of monsoon throughout the country and excess rainfall in major producing states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka which led to crop damage and delayed arrivals in the market. Decline in production [(-) 4.0 per cent in 2021-22 3rd AE over 2020-21 FE] also tightened supply in the early part of 2022. Potato prices increased during April-October 2022 (barring September) on account of lower production [(-) 5.0 per cent in 2021-22 3rd AE over 2020-21 FE], reflecting the impact of unseasonal rains during November-December 2021 and delay in arrivals of fresh crops. The government allowed free import of potato from Bhutan in July 2022 without any licence till June 30, 2023 to restrain positive price pressures. As cold storages released fresh stocks in the market, prices corrected from November 2022 onwards.  II.3.17 Prices of cereals and products (weight of 21.1 per cent in the CPI-Food and beverages) recorded steady growth in 2022-23, primarily driven by increase in rice and wheat prices. Wheat prices firmed up as domestic production declined in 2021-22 [(-) 1.7 per cent as per 2021-22 FE over 2020-21 FE] due to heat waves in major wheat producing states of Punjab and Haryana and decline in stock levels to below the buffer norms intermittently since August 2022. Price pressures were amplified by higher international prices due to global supply shortages which led to higher volume of exports (11.8 per cent year on year during April-November 2022), leading to reduction in domestic supply of wheat. The sharp increase in domestic prices led the government to impose restrictions on wheat exports since May 2022 and later additional curbs on exports of wheat products since August 2022 even as exports under the government-to-government channel continued. Price pressures in rice reflected substitution of wheat distribution under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) by rice along with a rise in volume of exports (by 5.2 per cent, y-o-y, in 2022-23) and decline in estimated kharif production [(-) 0.9 per cent in 2022-23 3rd AE over 2021-22 FE]. Supply-side measures by the government - imposition of 20 per cent export duty on non-basmati rice and prohibition of export of broken rice in September 2022 along with robust buffer stocks (which stood at 3.2 times the norm as on April 1, 2023) helped in keeping the price increase range bound. II.3.18 In the case of animal protein-rich items such as eggs, meat and fish (weight of 8.8 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages), price pressures were seen in meat and fish in Q1:2022-23 due to increase in feed and transportation costs (Chart II.3.9 a). Price pressures moderated subsequently due to a fall in seasonal demand on account of Sravana month and approval of an additional import of 0.55 million tonne of genetically modified soybean meal by the government in May 2022. However, price pressures re-emerged in September-October, before moderating thereafter. Egg prices remained volatile and were driven by rising feed costs as well. In the case of milk and products, prices increased throughout the year as major milk co-operatives, viz., Amul and Mother Dairy revised their retail prices upward by ₹2 per litre multiple times during the year citing rising feed cost pressures (Chart II.3.9 b). II.3.19 Price pressures in oils and fats (weight of 7.8 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) eased gradually since June 2022 as global prices of edible oils, particularly palm oil, declined sharply (Chart II.3.10). Edible oil prices increased sharply during March-May 2022 on account of a rise in global prices as the Ukraine conflict and imposition of export ban on crude palm oil by Indonesia in April 2022 severely impacted the supply of edible oils in the global market. Moreover, depreciation of the Indian Rupee on the back of high dependence on imports of edible oils also added to the rising domestic prices. The price momentum eased gradually with the softening of global prices, lifting of export ban and removal of export levy till October 31, 2022 by Indonesia. The government also undertook several supply-side measures which included extending zero per cent basic customs duty (BCD) on crude palm oil, sunflower and soybean oil till March 2024, reduction in BCD on refined soybean, and sunflower and palm oil to 17.5 per cent and 12.5 per cent (from 32.5 per cent and 17.5 per cent), respectively, and reduction of import duty on refined palm oil to zero till March 2024. In addition to these, the government also imposed stock limits on edible oils and oilseeds till December 31, 2022 and exempted BCD and agricultural infrastructural development cess (AIDC) on allocated Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) for import of 20 lakh metric tonne of crude soybean oil and sunflower oil for 2022-23. These measures together led to a steady decline in the prices of edible oils.

II.3.20 Inflation in prices of pulses (weight of 5.2 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) remained muted in 2022-23 on account of extension of imports of tur and urad under ‘free category’ till March 31, 2024, extension of zero AIDC on imports of lentils till March 2024 and higher overall production in 2021-22 (Chart II.3.11). But prices increased since August 2022 on account of a decline in estimated kharif production of both tur and urad by 18.7 per cent and 3.2 per cent, respectively, as per 3rd AE of 2022-23 over 2021-22 FE. Recent measures to boost food security, including raising government limit for procurement of tur, urad and masur from farmers to 40 per cent from 25 per cent and robust sowing of rabi crop contained price pressures since October. II.3.21 Inflation in fruits (weight of 6.3 per cent in CPI-Food and beverages) remained largely range bound during the year, primarily driven by movements in seasonal fruits prices. Spike in mango prices due to crop damage caused by heat waves and unseasonal rains led to sharp increase in price pressures in April 2022 which tapered off gradually with the increase in arrivals. Inflation in banana, papaya and other fresh fruits, however, remained elevated, driving up fruits inflation during February-March 2023. II.3.22 Among other food items, spices witnessed double digit inflation throughout the year 2022-23 averaging 16.2 per cent due to overall decline in domestic production [(-) 2.7 per cent as per 3rd AE of 2021-22 over FE 2020-21] in key spices particularly dry chillies, cumin and coriander. Fuel II.3.23 The contribution of the fuel group (weight of 6.8 per cent in CPI) to headline inflation decreased to 10.5 per cent in 2022-23 from 13.1 per cent in the previous year. Fuel inflation remained in double digit for a major part of the year driven by hardening of domestic LPG and kerosene prices in line with sharp increase in international prices (Chart II.3.12 and Chart II.3.13). Nevertheless, inflation moderated from its intra-year peak of 11.8 per cent in July 2022 as global crude oil prices moderated and price increases in LPG and electricity broadly remained muted.

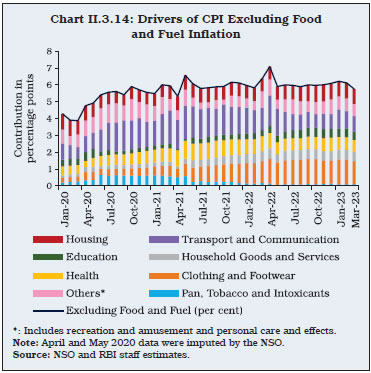

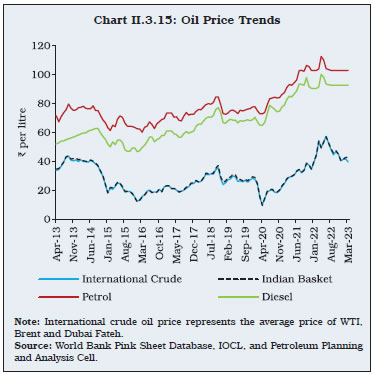

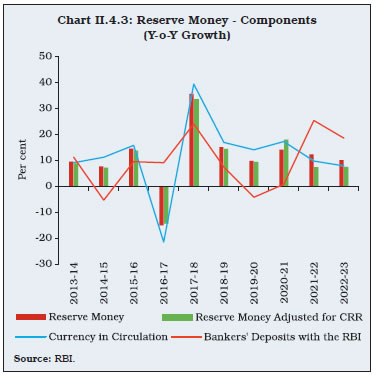

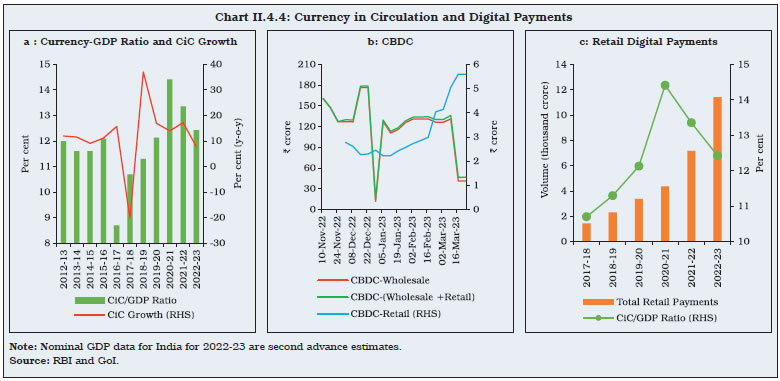

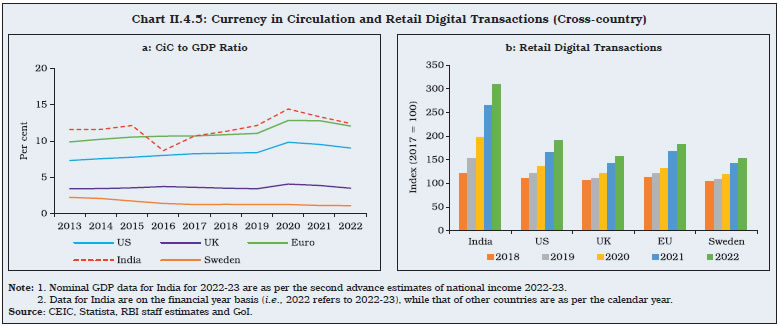

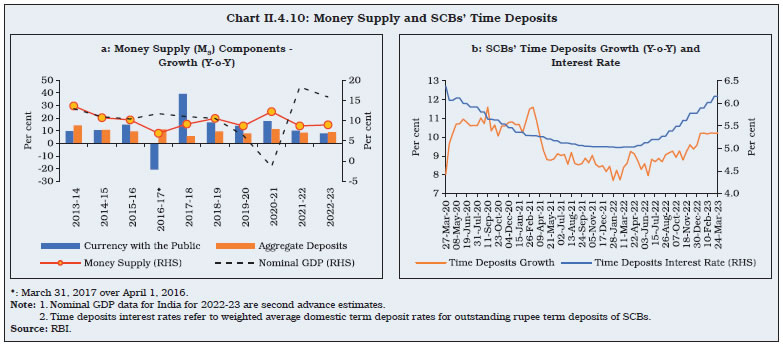

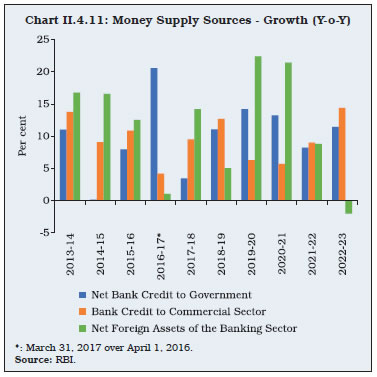

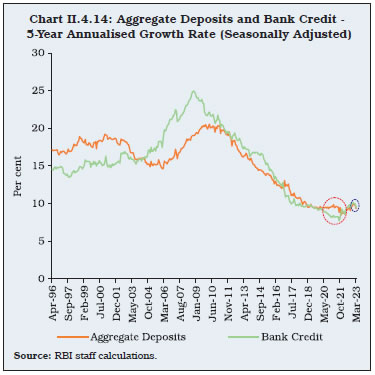

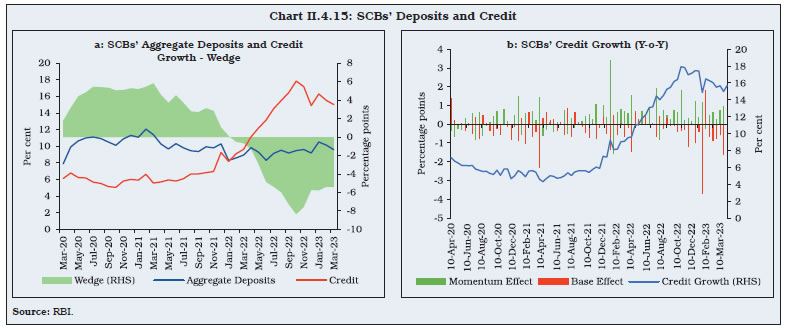

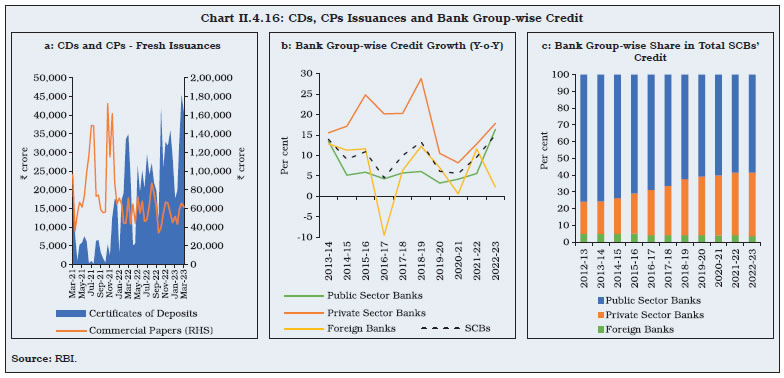

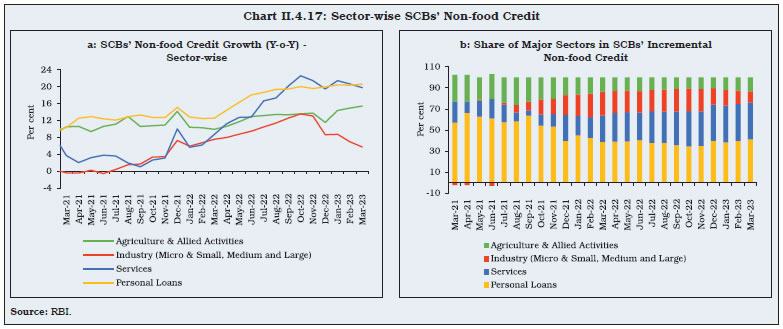

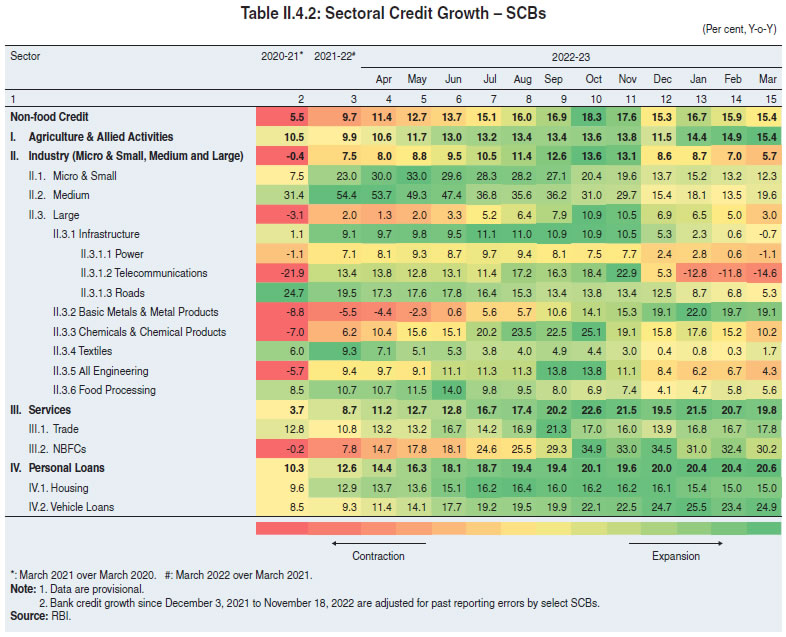

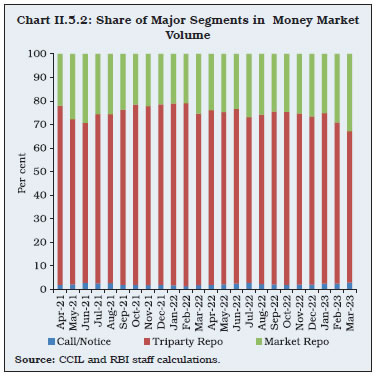

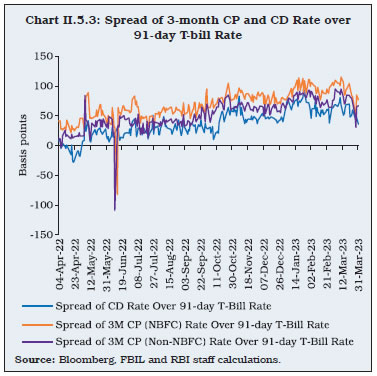

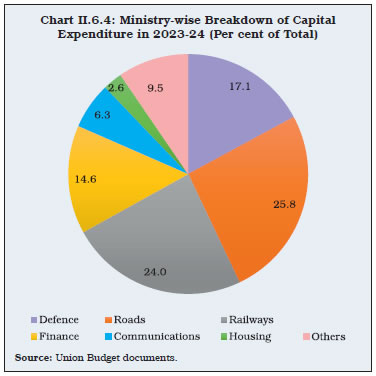

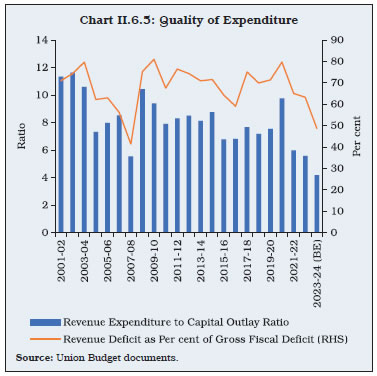

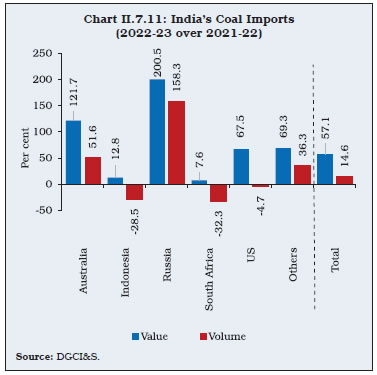

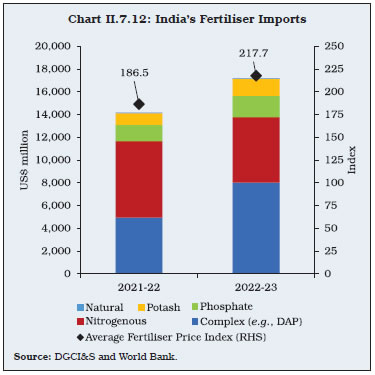

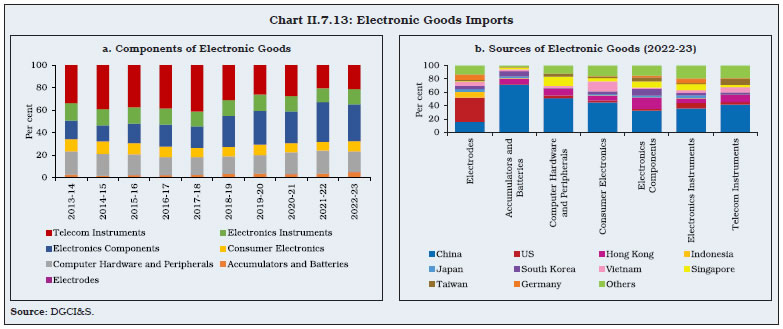

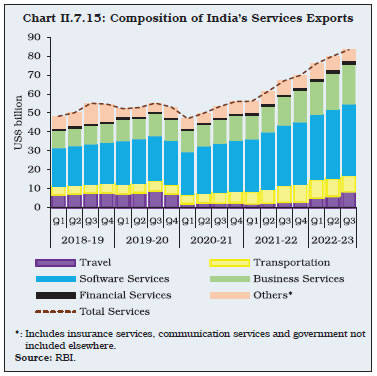

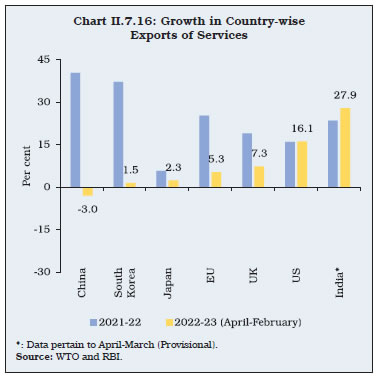

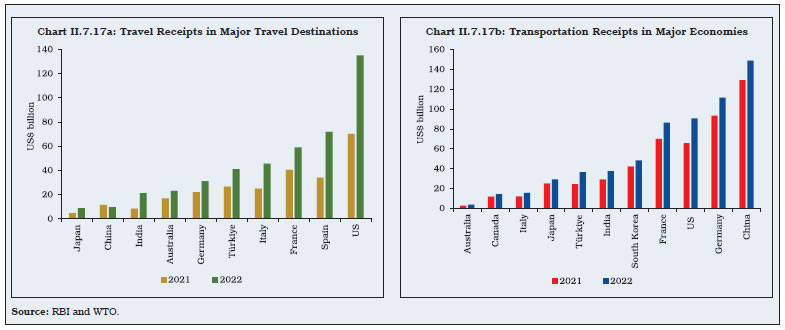

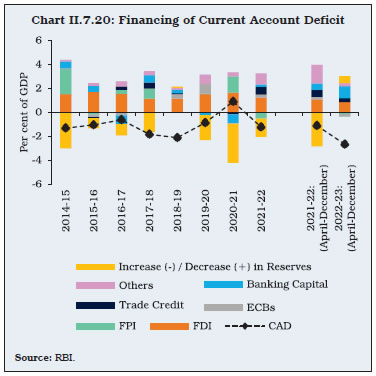

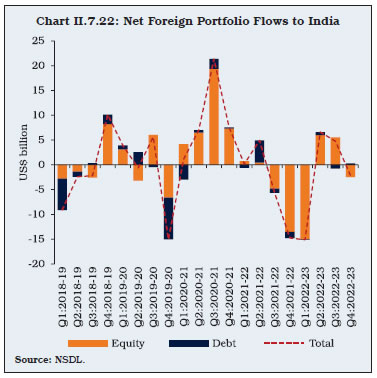

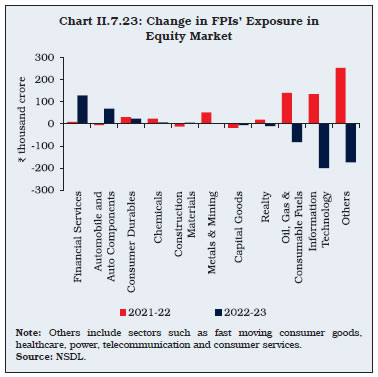

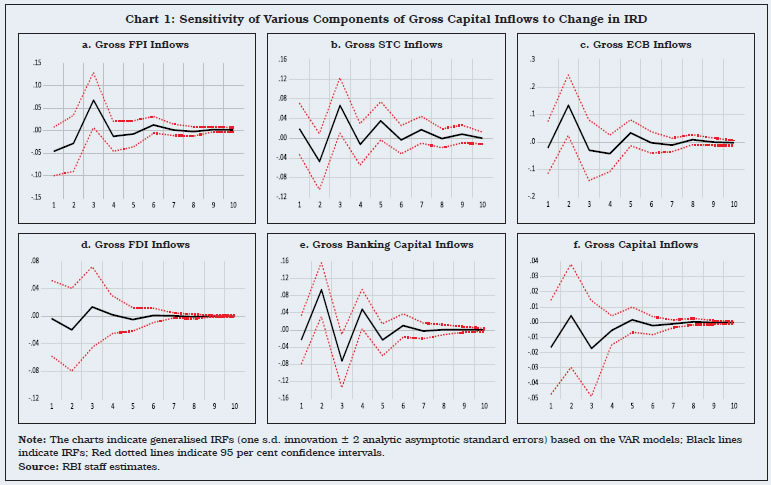

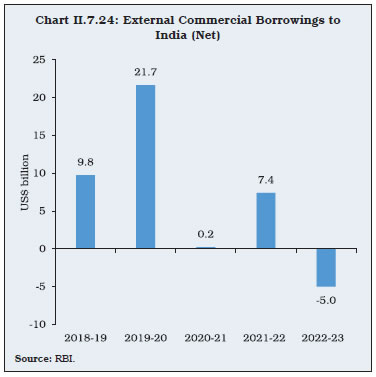

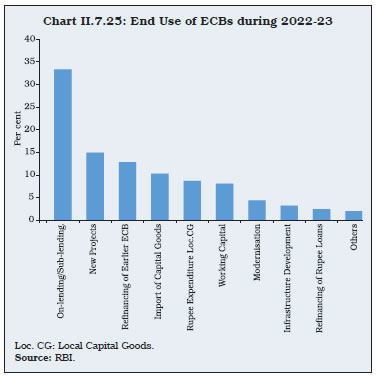

Inflation Excluding Food and Fuel II.3.24 Inflation excluding the volatile food and fuel items, i.e., core inflation, picked up to an average of 6.1 per cent in 2022-23 - a marginal increase from 2021-22, with a peak of 7.1 per cent in April 2022 (Chart II.3.14) [Appendix Table 4]. Core inflation remained sticky at around 6 per cent since May 2022 despite the excise duty cuts on petrol and diesel in May 2022, followed by a reduction in value added tax (VAT) by many state governments, with broad-based pressures observed across goods and services. II.3.25 Among the major constituents, inflation in transport and communication moderated gradually after the sharp spike in Q1:2022-23, reflecting increase in domestic prices of petrol and diesel in line with international prices (Chart II.3.15). Within transport and communication, prices of personal transport vehicles (viz., motor car, motor cycle and bicycle) increased, reflecting gradual pass-through of input costs pressures alongside a recovery in demand, while transport fares also increased with revisions in bus and taxi fares following the rise in the prices of petrol and diesel. Inflation in the health sub-group remained subdued as compared with the last year as the pandemic induced demand gradually eased with reduction in COVID-19 cases and normalisation of medical supplies. Broad-based increase in core prices was observed on account of pass-through of input costs to retail prices as more than 70 per cent of items registered higher than 4 per cent inflation rates during 2022-23 (Chart II.3.16).