by Anirban Sanyal, Shivangee Misra and Sanjay Singh^ This paper develops a quarterly Composite Leading Indicator (CLI) for GVA–Manufacturing using a two-stage procedure that combines systematic variable selection with subsequent aggregation. The indicator set—comprising commodity prices, survey-based expectations, industrial credit flows, and global variables—is identified through multiple validation techniques and then incorporated into machine-learning models, notably Random Forest and XGBoost. The resulting CLI exhibits a stronger leading property, yielding a cross-correlation of 0.86 at a one-quarter lead, compared with 0.72 contemporaneously. Its turning points consistently precede those of manufacturing GVA by one quarter, highlighting its usefulness for short-term monitoring and forecasting. Introduction Business cycle leading indicators are a vital component of macroeconomic surveillance, offering timely insights into emerging shifts in economic momentum. In particular, the leading business cycle indicators enable the identification of prospective turning points in the business cycle of the reference series, thereby providing early signals on evolving economic conditions. Against this backdrop, this article introduces a new leading indicator designed to track the real gross value added (GVA) growth of the manufacturing sector in India. Business cycle analysis has a long intellectual lineage, tracing its roots to the seminal contributions of Burns and Mitchell (1946) and the later empirical refinements of Stock and Watson (1989). Subsequent research by Moore (1982) and Zarnowitz & Boschan (1975) underscored the importance of cyclical synchronisation across economic indicators, setting the stage for systematic development of leading business cycle indicators across advanced and emerging economies. International experience highlights considerable heterogeneity: in Italy, monetary and financial variables have been found to lead domestic cycles by 12–16 months, with international cycles exhibiting a high degree of co-movement (Altissimo et al., 2000); for Turkey, a leading indicator index was constructed from nine key economic series spanning imports, monetary aggregates, and fiscal expenditures (Murutoglu, 1999). Many such indicators draw on business and consumer survey data, with evidence—such as Finland’s industry survey—demonstrating strong correlations between forward-looking expectations and subsequent industrial production (Penna Urrila, 2001). Collectively, composite leading indicators have proven useful in anticipating turning points in reference series, thereby strengthening short-term forecasting and policy assessment (Altissimo et al., 2000; Murutoglu, 1999). In the Indian context, Roy and Biswas (2012) developed a composite leading indicator (CLI) for the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), employing both growth-cycle and growth-rate-cycle approaches to track turning points in overall industrial activity. That indicator, constructed for the 2004–05 base, served as a timely gauge of cyclical dynamics of industrial growth in India at the time. Since then, however, the role of IIP in national accounts has diminished, and the index itself has undergone a base revision to 2011–12. Given the centrality of the manufacturing sector in gross value added (GVA) and the need for more robust high-frequency cyclical assessment, this article proposes a composite leading indicator for GVA-manufacturing at a quarterly frequency. The construction of the CLI for GVA–manufacturing in this study follows a structured two-step framework, supported by a range of cross-validation techniques. In the first stage, potential leading variables are identified on the basis of their signal strength vis-à-vis the reference series, complemented by a machine-learning-based kitchen-sink approach to further refine the selection. The cyclical characteristics of the shortlisted indicators are subsequently examined through wavelet analysis to ensure robustness of their leading properties. In the second stage, these selected variables are combined using multiple aggregation methods to derive the composite indicator. The resulting CLI encompasses indicators reflecting cost pressures, external demand, policy uncertainty, and credit flows to industry, and the proposed CLI exhibits a lead of one quarter over the growth rate cycle of GVA manufacturing. Rest of the article is organised as follows – Section II provides background and current practice of CLI. The empirical framework is noted in Section III. Section IV documents the data sources and frequency. Empirical findings are listed in Section V. Within empirical findings, the variables selected through various approaches are mentioned, followed by the findings of the wavelet analysis. Later, CLI is constructed using the selected variables through various aggregation approaches. The validation of the leading property of each CLI is assessed through turning point analysis. Lastly, the findings are summarised in the concluding remarks in Section VI. II. Literature Review and Current Practice of Composite Leading Indicator The construction of the leading indicator is guided by the requirement that it attain its turning points—both peaks and troughs—ahead of the coincident index, which captures contemporaneous economic conditions. This property underpins its usefulness in forecasting near-term fluctuations and supports forward-looking decision-making. As such, the leading indicator provides policymakers, financial analysts, investors, and firms with a systematic means of anticipating shifts in macroeconomic momentum. When used in conjunction with the coincident index, the leading economic indicator enhances the monitoring architecture for the Indian economy and delivers early warning signals of prospective expansions or contractions in activity (Dua and Banerji, 1999). The analytical foundations of this approach trace back to Mintz’s (1969, 1972 and 1974) development of the growth-cycle methodology for identifying cyclical turning points. Earlier work by Burns and Mitchell (1967) established the empirical significance of coincident and leading indicators for business-cycle analysis. Building on these contributions, Klein and Moore (1985) advanced the study of economic cycles at the National Bureau of Economic Research, setting the precedent for modern indicator-based monitoring systems. Among the existing studies for India, Chitre (1982) documents substantial synchronicity among a wide range of Indian macroeconomic indicators around their long-run trends using a growth-cycle framework. His analysis spans non-agricultural net national product, industrial output, capital formation, monetary aggregates, and bank credit, among others, from which fifteen variables were ultimately selected to construct a composite index intended to proxy aggregate economic activity. The study identifies five distinct growth cycles for the Indian economy between 1951 and 1975. Using annual data from 1950 to 1985, Hatekar (1993) similarly identifies turning points in major macroeconomic aggregates and examines their comovement patterns within a growth-cycle perspective. Dua and Banerji (1999), applying the traditional NBER methodology, derived both classical business cycles and growth-rate cycles for India and develop a composite leading index drawing on indicators from the monetary, construction, and corporate sectors. Expanding the empirical base, Chitre (2001) analyzes 94 monthly series for 1951–1982, and derived a reference cycle from eleven indicators using diffusion indexes, composite indexes, and principal components methods. This paper is closely related to Roy and Biswas (2012) which proposes a CLI for the Index of Industrial Production using eight high-frequency indicators (HFIs) (Table 1). To account for differences in scale across the HFIs and the IIP, the authors apply a cumulative density function transformation prior to aggregation. Lead–lag relationships are assessed through cross-correlation analysis between each candidate series and the reference series. Following indicator selection, the target series (IIP) is regressed on lagged values of the individual indicators; the resulting adjusted R2 values—interpreted as the share of variation in the target explained by each indicator and its lags—serve as a metric of leading performance. These adjusted R2 values are subsequently employed as weights in the construction of the composite index. III. Empirical Framework The CLI for GVA-Manufacturing, proposed in this article has been constructed in two phases. In the first phase, the HFIs are selected using various variable selection methods. The selected indicators are aggregated to derive CLI in the phase 2. The variable selection is carried out through signal extractions where the leading property of each variable is tested individually and in a collective manner. The signal strength of each HFI is validated using cross correlation analysis, regression estimates using ordinary least squares (OLS), quantile regression, mutual information criteria and dynamic time warping (DTW). Using the kitchen sink approach the information on the leading properties of multiple indicators is assessed through recursive feature eliminations (RFE) with k-nearest neighbour (k-NN), random forest and XGBoost approach. Further, different sets of HFIs are generated from the common variables selected by various methods. Lastly, HFIs having high wavelet coherence are selected as additional group of the selected variables. Additionally, indicators appearing in at least one criteria are taken together as separate sets of variables through various combinations to improve the information contents. A brief discussion of the methods used for variable selection is provided in Annex I. | Table 1: Indicators Used in CLI for Industry | | Sr. No. | Indicator | Weight | | 1 | Commercial Motor Vehicle Production | 11.4 | | 2 | Dollar/Rupee Exchange Rate (Monthly Average) | 13.3 | | 3 | Monetary Aggregate M1 | 19.7 | | 4 | Non-Oil Imports | 10.8 | | 5 | Railway Freight | 6.3 | | 6 | BSE SENSEX Index | 15.8 | | 7 | Steel Production | 18.0 | | 8 | CP Spread | 4.8 | | Source: Roy and Biswas (2012). | The aggregation of the selected indicators is conducted through various methods, namely, simple average, weighted average with various choices of weights and dynamic factor models (DFMs). The weighted average approach is developed using inverse standard deviations and correlation as weights. DFM is employed to extract the common signal strength from the selected variables. Lastly, the CLI is smoothened using HP filter to remove the irregular variations in the data. The lambda value in the HP filter (lambda=4) is selected based on the cross-validation technique used by Grehmann and Yetman (2018). Lastly, the performance of the proposed CLI is carried out using cross-correlation, coherence and turn-around point analysis proposed by Bry and Boschan (1971) and later, modified for quarterly data by Harding & Pagan (2012). IV. Data Used The high frequency economic indicators which are likely to influence the economic activities with a lead period, are selected from major dimensions, namely, i) Domestic demand condition; ii) Domestic industrial production; iii) Domestic price conditions; iv) Foreign trade; v) Employment condition; (vi) Trade, transport and other services indicators; (vii) Public finance and payment Indicators; (viii) Exchange rate; (ix) Global commodity price; (x) Policy uncertainty; (xi) Forward looking survey – Industrial Outlook Survey and PMI Manufacturing; (xiii) Cost of borrowing proxy; and (xiv) Global economic indicators. The variables are transformed into year-on-year (y-o-y) growth except for the borrowing cost (i.e. interest rate) proxy, policy uncertainty and exchange rate. The interest rate proxies, and policy uncertainties are used in level values. Exchange rates are transformed into quarter-on-quarter (q-o-q) annualized growth rate. The detailed list of the HFIs considered within each segment is provided in Annex II. The data used for this analysis spans from April 2013 to December 2024. As the reference series (i.e., GVA-manufacturing) is available at quarterly interval, the variable selection is carried out at quarterly frequency and the CLI is also calculated at quarterly frequency. V. Empirical Findings V.1 Variable Selection The correlation analysis of the HFIs show very high negative correlation of global commodity prices with GVA manufacturing. Within commodity prices, crude oil prices affect the manufacturing growth with lag of 1 – 2 quarters. IMF all commodity prices (excluding gold) also drags manufacturing growth with a lag of 1 - 2 quarters. Merchandise imports moderate manufacturing growth in 1-2 quarter lag, while non-oil exports improve growth in the manufacturing sector with a lag of one quarter. Among the global variables, US non-farm payroll employment has positive correlation with GVA manufacturing with one quarter lead (Table 2). | Table 2: Cross Correlation Estimates of GVA-Manufacturing Growth with Top 10 HFIs | | Variable | Pearson | Kendall | Spearman | | IMF Crude Oil Price (-2) | -0.48 | -0.40 | -0.53 | | IMF industrial Input (-2) | -0.50 | -0.39 | -0.56 | | IMF All Commodity Price (-2) | -0.48 | -0.38 | -0.53 | | IMF All (Excl. Gold) Commodity Price (-2) | -0.48 | -0.38 | -0.54 | | Non-oil exports (-1) | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.54 | | Real Credit to Industry (-2) | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.51 | | IMF Metal Prices (-2) | -0.41 | -0.37 | -0.49 | | Merchandize Imports (-2) | -0.44 | -0.35 | -0.52 | | US Non-farm Payroll Employment SA (-1) | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.57 | | WPI Industrial Raw Material (-2) | -0.42 | -0.33 | -0.45 | Note: The number indicated in the parentheses indicate the lags of the variables, measured in quarters.

Source: Authors’ calculation. | The variable selection using regression estimates is carried out using OLS regression and quantile regression (for median). The regression includes the lagged value of GVA - manufacturing as additional regressor to knock out any time persistent effects in the data generating process of GVA - manufacturing. The regression coefficient attached to the HFI is extracted if the coefficient estimate is statistically significant at 10 per cent level of significance.1 The regression estimates show similar effects of commodity prices on GVA – manufacturing growth. Railway freight and petroleum consumption appear to have significant positive relation with GVA - manufacturing. Non-food credit and real credit to industry also improves the manufacturing growth with a lead of 2 quarters. The borrowing cost proxy, namely, G-Sec 10-year yield and treasury bill rate increases the borrowing burden and thereby, moderates the manufacturing growth. Merchandise imports also moderate the manufacturing growth (Table 3). | Table 3: Regression Coefficients of GVA - Manufacturing with HFIs | | Variable | OLS Regression | Quantile Regression

(Median) | | Indian Basket Crude Oil Price (-1) | -1.40 | -0.54 | | WPI Manufacturing (-1) | -1.03 | -0.45 | | Railway Freight Traffic (-2) | 1.03 | 0.31 | | Petroleum Consumption (-1) | 0.86 | 0.26 | | Real Credit to Industry (-2) | 0.67 | 0.23 | | Real Non-food Credit (-2) | 0.62 | 0.22 | | G-Sec 10 Yrs Yield (-2) | -0.98 | -1.10 | | T-Bill 91 Days Rate (-1) | -1.05 | -0.94 | | WPI Headline (-1) | 0.64 | -0.29 | | Merchandize Imports (-2) | -0.43 | -0.48 | Note: The number indicated in the parentheses indicate the lags of the variables, measured in quarters.

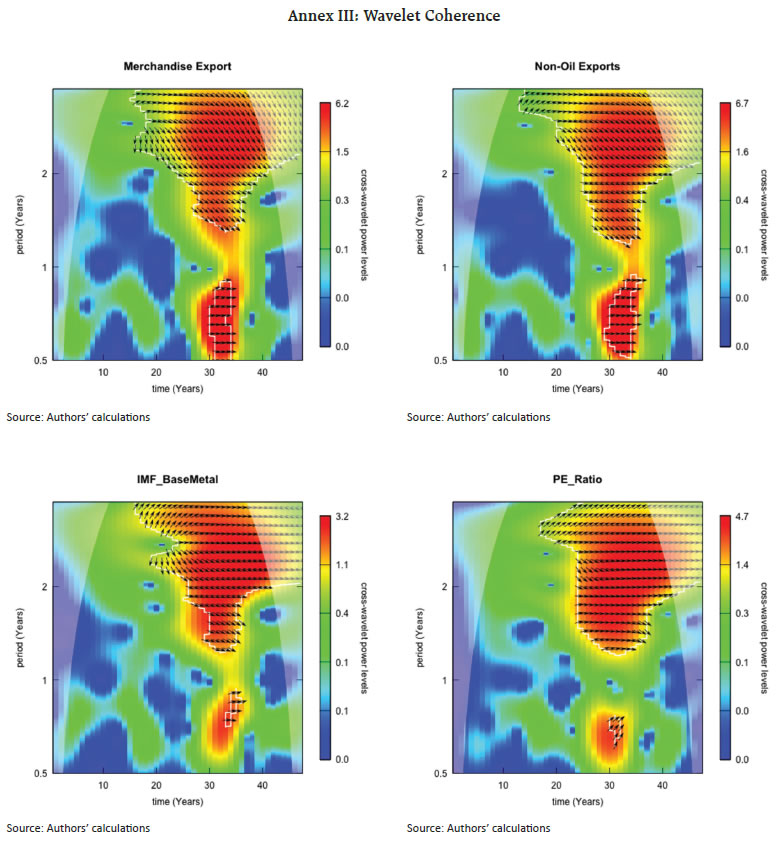

Source: Authors’ calculation. | Lastly, the variable selection using mutual information, cosine similarity and (L1 and L2) distance measure2 filters capacity utilization, outlook of raw material cost, PMI manufacturing index and its components, trade - transport indicators, borrowing cost proxy and commodity prices (Table 4). The variables selected from the signal strength of the individual HFIs ignores the interactions among HFIs. For that, all variables are used simultaneously in a single framework (with different lags) to identify the suitable variables. This kitchen-sink approach uses three broad methods to identify the important variables – recursive feature elimination (RFE), random forest (RF) and XGBoost. Apart from the commodity prices, global indicators and policy uncertainties are selected as leading variables of GVA - manufacturing growth. Real non-food credit and credit to industry are selected in RFE and Random Forest. The domestic economic indicators and borrowing cost proxies are also filtered (Table 5). V.2 Cross Validation of the Business Cycle Properties of Selected HFI Combining the variables selected through various methods provides a comprehensive list of HFIs having some leading information about GVA-manufacturing growth. The information content of the selected HFIs is verified using wavelet analysis. The cross-wavelet analysis provides the degree of coherence between the HFIs and the benchmark series (i.e., GVA-manufacturing).3 | Table 5: Variables Selected in RFE, RF and XGBoost | | Variables | Lead in Quarters | | Method = RFE | | US Non-farm Payroll Employment (SA) | 1 | | International Air Passenger Traffic | 2 | | European EPU | 2 | | Real Non-food Credit | 1 | | IOS Cost of Raw Material (Expectation) | 1 | | T-Bill 91 Days Yield | 2 | | IMF All (Excl. Gold) Commodity Prices | 1 | | Method = Random Forest | | Real Credit to Industry | 1 | | Global EPU | 1 | | Cement Production | 1 | | G-Sec 10 Years Yield | 2 | | USA EPU | 1 | | WPI Headline | 2 | | Commercial Motor Vehicle Sales | 1 | | India EPU | 1 | | Method = XGBoost | | International Cargo Traffic | 1 | | Global EPU | 1 | | WCMR | 1 | | Exports to Emerging and Developing Asia | 2 | | Domestic Air Passenger Traffic | 1 | | WPI Manufacturing | 1 | | High Speed Diesel | 1 | | US Non-farm Payroll Data | 1 | | IIP Consumer Durables | 1 | | IIP Consumer Non-durables | 1 | | Source: Authors’ calculations | The wavelet coherence estimates shows that GVA manufacturing growth shows high coherence with eight core industries, merchandise exports, IIP use-based classifications, employment from US Non-farm payroll, Indian basket crude oil price, cement production and US IIP (Table 6). | Table 6: Coherence from Cross Wavelet Analysis | | Series | Coherence Period

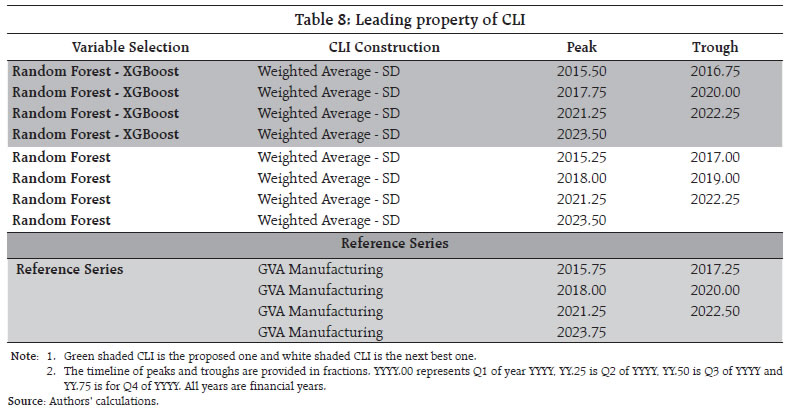

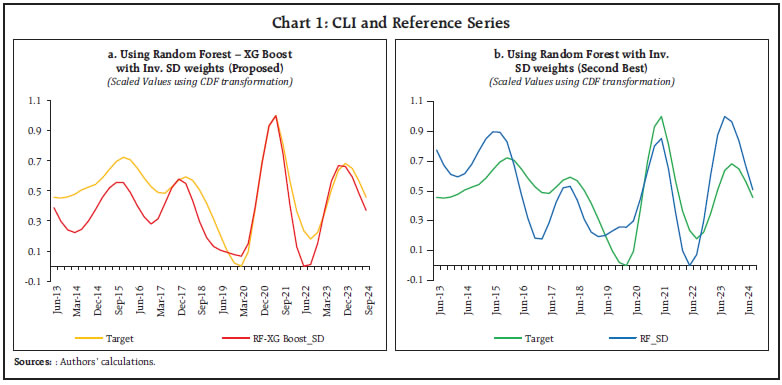

(in quarters) | Coherence | | Eight Core: Overall | 2 | 0.78 | | Merchandise Export | 2 | 0.75 | | IIP Intermediate goods | 2 | 0.73 | | IIP Primary goods | 2 | 0.73 | | US Non-farm Payroll (SA) | 2 | 0.68 | | IIP Infrastructure/ construction goods | 2 | 0.64 | | Indian Basket Crude Oil Price | 2 | 0.59 | | Cement Production | 2 | 0.59 | | WPI IRM | 2 | 0.59 | | US IIP | 2 | 0.59 | | Source: Authors’ calculations | The wavelet coherence plot also confirms the leading property of these indicators with GVA-manufacturing in 1-2 quarter lead. This common set of indicators having high coherence, are also selected as separate set of variables (along with various other subsets of variables from the previous selections) in the variable selection set (Annex III). A short description of interpretation of the wavelet charts is provided in Annex IV. a. Composite Leading Indicator The CLI is constructed using the selected HFIs from different methods. For each selection of HFI, CLI is constructed using simple average, weighted average and DFM. Following this approach, 48 different CLI are constructed and the performance of each CLI is validated using cross-correlation and turnaround point analysis for quarterly data. The cross-correlation is checked with lead of 1 quarter and 2 quarters. The cross-correlation results shows that variables selected from Random Forest - XGBoost and combined using inverse standard deviation weights, provide the highest tracking at 1-2 quarter lead. CLI from random forest also provide a better tracking than others (Table 7). The detailed list of cross-correlation estimates is provided in Annex V.  Next, the turnaround point analysis was carried out on the proposed CLI and the reference series using Harding & Pagan (2002) approach. The turnaround points of CLI are mapped with the reference series to track the leading property. CLI based on Random Forest with XGBoost has one quarter lead, whereas the Random Forest has lead of average one to two quarters (Table 8). Lastly, the time series plot of the proposed CLI and reference series establish the leading properties of the CLI visually except for the COVID period. The economic disruption during COVID pandemic led to broad based slowdown in Indian economy followed by a gradual recovery. The extent of recovery varied across segments which weakened the leading property of CLI during the recent pandemic period (Chart 1). Following the derivation, CLI is proposed using variables selected from Random Forest - XGBoost criteria and aggregating those using inverse standard deviation as weights. The selected variables are listed in Table 9.  It may be mentioned that the business cycle exhibits long-term pattern which evolves over time. For business cycle analysis using quarterly data, it is generally recommended to have a time series length of at least 30 to 50 years (i.e., 120 to 200 quarterly observations). This duration allows for the identification of multiple complete business cycles, which typically last between 5 to 10 years (OECD, 2008; Canova, 1998). A longer time series also helps in improving the reliability of statistical methods used in trend-cycle decomposition, filtering techniques (e.g., HP filter), and econometric modelling. In this analysis, 12 years data is used for deriving the leading indicator of GVA-manufacturing which is reasonable but may not be sufficient to study longer cycles, particularly due to the presence of COVID-19 led disruptions. The post pandemic data spans for two years which is insufficient to understand any changes in the data generating process of the economic variables. Following the data limitations and disruptions due to the COVID pandemic, it is recommended to revisit the construction of CLI at regular interval with better data availability.

| Table 9: Variables selected in Random Forest and Mutual Information | | Cement Production | WPI Headline | | Commercial Motor Vehicle Sales | WPI Manufacturing | | IIP Consumer Durable | G-Sec 10 Years Yield | | IIP Consumer Non-durable | WCMR | | High Speed Diesel | IMF All (Excl. Gold) Commodity Prices | | International Air Cargo | Exports to Emerging and Developing Asia | | Domestic Air Passenger Traffic | US Non-farm Payroll Employment | | Real Credit to Industry | Global EPU | | India EPU | | VI. Concluding Remarks This paper proposed a composite leading indicator for tracking the growth rate cycle of GVA Manufacturing using various high frequency indicators. Among the high frequency indicators, commodity prices, use-based classification of IIP, forward looking survey-based indicators, credit disbursed to industry, policy uncertainty and global commodity prices appeared to possess leading property on GVA manufacturing growth. The CLI constructed using random forest and XGBoost exhibits the highest tracking power with cross correlation of 86 per cent at lag of one quarter (contrary to 72 per cent contemporaneous correlation). The turnaround points of the constructed CLI leads the GVA-manufacturing turnaround points by one quarter. The leading property of the proposed CLI shows robustness in the pre-COVID period and post-pandemic recovery period. Reference Altissimo, Filippo, Alessandro Bassanetti, Roberto Cristadoro, Mario Forni, Marco Hallin, Marco Lippi, and Giovanni Veronese (2000). A Real Time Coincident Indicator of the Euro Area Business Cycle. European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 42. Frankfurt: European Central Bank. Berndt, D. J., and Clifford, J. (1994). Using Dynamic Time Warping to find patterns in time series. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (AAAI Workshop), 359-370. Boschan, Charlotte (1975). Cyclical Analysis of Time Series: Selected Procedures and Computer Programs. National Bureau of Economic Research Technical Paper No. 20. New York: NBER. Bry, G., & Boschan, C. (1971). Cyclical analysis of time series: Selected procedures and computer programs. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Burns, A. F., and Mitchell, W. C. (1946). Measuring Business Cycles. National Bureau of Economic Research. Canova, F. (1998). Detrending and business cycle facts. Journal of Monetary Economics, 41(3), 475-512. Chitre, V. S. (1982). Growth Cycles in the Indian Economy. Gokhale Institute of Politics & Economics / Artha Vijnana, 158 pp. Chitre, Vikas (2001). Indicators of Business Recessions and Revivals in India: 1951-1982. Indian Economic Review, 36(1), pp. 79–105. Cover, T. M., and Thomas, J. A. (2006). Elements of Information Theory (2nd ed.). Wiley. Diebold, Francis X., & Rudebusch, Glenn D. (1991). Forecasting Output with the Composite Leading Index: A Real-Time Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 86(415), 603–610. Drehmann, Mathias & Yetman, James (2018). Why You Should Use the Hodrick-Prescott Filter — At Least to Generate Credit Gaps. BIS Working Papers No. 744, Bank for International Settlements. Dua, Pami & Banerji, Anirvan (1999). An Index of Coincident Economic Indicators for the Indian Economy. Journal of Quantitative Economics, 15, 177-201. Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. Grehmann, K., & Yetman, J. (2018). How monetary policy affects economic conditions: Evidence from cross-country data. BIS Working Paper No. 729. Harding, Don & Pagan, Adrian (2002). Dissecting the Cycle: A Methodological Investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49(2), 365–381. Hatekar, N. H. (1993). The short-term dynamics of money and output in India. Mimeograph, University of Bombay, Bombay. Huang, A. (2008). Similarity measures for text document clustering. Proceedings of the Sixth New Zealand Computer Science Research Student Conference (NZCSRSC), 49-56. Klein, Philip A. & Moore, Geoffrey H. (1985). Monitoring Growth Cycles in Market-Oriented Countries: Developing and Using International Economic Indicators. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger / NBER Studies in Business Cycles. Koenker, R., and Bassett, G. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 33-50. Mintz, Ilse (1961). World Imports and United States Business Cycles. American Exports during Business Cycles, 1879–1958, pp. 35–41. National Bureau of Economic Research. Mintz, I. (1969). Dating postwar business cycles: Methods and their application to Western Germany, 1950–1967. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Mintz, I. (1972). Dating postwar business cycles: Methods and their application to France, 1949–1967. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Mintz, I. (1974). Dating postwar business cycles: Methods and their application to Italy, 1950–1967. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. Moore, Geoffrey H. (1982). Business Cycles, Inflation, and Forecasting. 2nd Edition. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Studies in Business Cycles, No. 24. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Penna Urrila, M. (2001). Business cycle asymmetry: An application of nonlinear models to the Finnish economy. Bank of Finland Discussion Paper No. 19/2001. Murutoglu, G. (1999). Business cycles: Persistence, asymmetries and international transmission. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. OECD (2008). OECD System of Composite Leading Indicators: A Revised Framework. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Roesch, A., & Schmidbauer, H. (2018). WaveletComp: computational wavelet analysis. R package version, 1(1). Roy, I., and Biswas, D. (2012). Construction of a composite index of leading indicators for the index of industrial production in India. Journal of Quantitative Economics, 10(1), 17-31. Stock, J. H., and Watson, M. W. (1989). New indexes of coincident and leading economic indicators. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 4, 351-393. Stock, J. H., and Watson, M. W. (1999). Business cycle fluctuations in US macroeconomic time series. Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1, 3-64. Urrila, Penna (2001). Suhdanneindikaattoreiden käyttö talouskehityksen seurannassa. (Working Paper No. 780). ETLA — Elinkeinoelämän tutkimuslaitos, Helsinki. Zarnowitz, Victor & Moore, Geoffrey H. (1986). Major Changes in Cyclical Behavior, The American Business Cycle: Continuity and Change, edited by Robert J. Gordon, 519–582. Chicago: University of Chicago Press / National Bureau of Economic Research

Annex I : Methods used for Variable Selection Cross-Correlation: Cross-correlation analysis is a statistical technique used to measure the relationship between two time series at different lags, helping to identify lead-lag relationships and synchronicity between variables. In business cycle analysis, it is often employed to examine how economic indicators move in relation to the overall cycle, determining whether they are leading, coincident, or lagging indicators (Stock and Watson, 1999). A high cross-correlation at a positive lag suggests that one variable tends to lead the other, while a strong correlation at zero lag indicates simultaneous movement. This method is widely used in macroeconomic research to assess the predictive power of economic indicators and understand transmission mechanisms across sectors. Regression Analysis Regression analysis using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is a fundamental statistical method for estimating relationships between dependent and independent variables in economic and financial research. OLS minimizes the sum of squared residuals to derive the best-fitting linear equation, making it widely used for business cycle analysis, forecasting, and policy evaluation (Greene, 2012). Quantile Regression Quantile regression is an econometric technique that extends traditional Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression by estimating the conditional relationship between variables at different points of the outcome distribution (Koenker and Bassett, 1978). Unlike OLS, which models the mean effect, quantile regression provides a more comprehensive view of the data by capturing heterogeneous effects across quantiles. This is particularly useful in business cycle analysis, where economic relationships may vary during recessions and expansions. Cosine Similarity Cosine similarity is a metric used to measure the similarity between two non-zero vectors by computing the cosine of the angle between them. It is widely applied in text analysis, machine learning, and economic research to compare patterns in high-dimensional data. Unlike Euclidean distance, cosine similarity focuses on the direction rather than the magnitude of vectors, making it useful for comparing time series with different scales. In business cycle analysis, it can be employed to assess the similarity of economic indicators or compare the cyclical patterns of different countries over time. A value close to 1 indicates high similarity, while a value near 0 suggests no correlation (Huang, 2008). Mutual Information Mutual information (MI) is an information-theoretic measure that quantifies the dependency between two random variables by capturing both linear and nonlinear relationships (Cover and Thomas, 2006). Unlike correlation, which only detects linear dependencies, MI assesses the reduction in uncertainty about one variable given knowledge of another. In business cycle analysis, MI can be used to evaluate the strength of associations between macroeconomic indicators, such as GDP growth and inflation, across different economic conditions. Dynamic Time Warping Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) is an algorithm used to measure the similarity between two time series by allowing non-linear distortions in the time axis (Berndt and Clifford, 1994). Unlike traditional distance metrics, such as Euclidean distance, DTW aligns sequences of different lengths or with temporal shifts by finding an optimal warping path that minimizes the cumulative distance between corresponding points. This makes it particularly useful in business cycle analysis, where economic indicators may exhibit phase shifts or different speeds of fluctuation across countries or industries. Annex II : List of HFI Considered for CLI | IIP Data | Exchange Rate | | IIP Manufacturing | REER | | IIP Headline Index | NEER | | IIP Primary Goods | INR - USD Exchange Rate | | IIP Capital Goods | Global Commodity Price | | IIP Intermediate Goods | IMF All Commodity Prices | | IIP Infrastructure Goods | IMF Commodity prices excluding Gold | | IIP Consumer Durables | IMF Commodity Price of Industrial Raw Material | | IIP Consumer Non-durables | IMF Commodity Price of Metals | | Global Trade | IMF Commodity Price of Base Metals | | Exports to Emerging and Developing Asia | IMF Commodity Price of Fuel | | Exports to Europe | IMF Commodity Price of Crude Oil | | US Non-farm payroll Data | IMF Commodity Price of Coal | | US IIP | World Bank Price - Aluminium | | China IIP | World Bank Price - Iron | | External Trade | World Bank Price - Copper | | Merchandize Exports | World Bank Price - Lead | | Merchandize Imports | World Bank Price - Tin | | Non-oil non-gold imports | World Bank Price - Nickel | | Non-oil exports | World Bank Price - Zinc | | Export of services | Indian Basket Crude Oil Price | | Import of services | WTI Crude Oil Price | | Import of Capital Goods | Brent Crude Oil Price | | Employment Condition | Dubai Crude Oil Price | | CMIE Labour Force Participation - All India | PMI Data | | CMIE Labour Force Participation - Urban | PMI Index | | CMIE Labour Force Participation - Rural | PMI Output | | CMIE Unemployment Rate - All India | PMI New Orders | | CMIE Unemployment Rate - Urban | PMI Employments | | CMIE Unemployment Rate - Rural | PMI Supplier Delivery Time | | CMIE Employment Rate - All India | PMI Stock of Purchase | | CMIE Employment Rate - Urban | PMI Input Prices | | CMIE Employment Rate - Rural | PMI Quantity of Purchase | | NAUKRI Job Speak Index | PMI Stocks of Finished Goods | | MGNREGA Work Demand | PMI New Export Orders | | Payment and Public Finance | PMI Output Prices | | RTGS Payments | PMI Backlog of Work | | UPI Payments | PMI Future Output | | E-Way Bills | Eight Core Headline | | GST Collection | Coal Production | | Revenue Expenditure (less interest payments and subsidy) of Central Government | Crude Oil Production | | Fertiliser Sales | Natural Gas Production | | | Petroleum Products production | | | Fertilizers production | | | Steel Production | | | Cement Production | | | Electricity Production |

| Domestic Price Condition | USA Policy Uncertainty - Newspaper Based | | WPI Headline Index | Chine Policy Uncertainty | | WPI Food Prices | European Union Policy Uncertainty - Newspaper | | WPI Primary Articles | Germany Policy Uncertainty - | | WPI Fuel and Power | Italy Policy Uncertainty - | | WPI Manufactured Items | UK Policy Uncertainty - | | WPI Industrial Raw Material | France Policy Uncertainty - | | CPI Headline | Spain Policy Uncertainty - | | CPI Index excluding Food, Fuel and Beverages | PE Ratio of listed companies | | Consumption Indicators | Realized volatility of BSE Companies | | Finished Steel Consumption | IOS and OBICUS Data | | Petroleum Consumption | Industrial Outlook Survey - Production (Expectation) | | High Speed Diesel Consumption | Industrial Outlook Survey - Order Book (Expectation) | | Motor Spirit Consumption | Industrial Outlook Survey - Capacity Utilization (Expectation) | | Aviation Turbine Fuel Consumption | Industrial Outlook Survey - Exports (Expectation) | | Trade, Transport and Demand Indicators | Industrial Outlook Survey - Imports (Expectation) | | Domestic Air Passenger Traffic | Industrial Outlook Survey - Inventory of Raw Material (Expectation) | | International Air Passenger Traffic | Industrial Outlook Survey - Inventory of Finished Goods (Expectation) | | Domestic Air Cargo | Industrial Outlook Survey - Employment (Expectation) | | International Air Cargo | Industrial Outlook Survey - Financial Condition (Expectation) | | Railway Freight | Industrial Outlook Survey - Cost of Finance (Expectation) | | Port Traffic | Industrial Outlook Survey - Cost of Raw Material (Expectation) | | Passenger Vehicle Sales (Wholesale) | Industrial Outlook Survey - Selling Price (Expectation) | | Passenger Vehicle Sales (Wholesale) - LMV | Industrial Outlook Survey - Profit Margin (Expectation) | | Two Wheeler Sales (Wholesale) | Industrial Outlook Survey - Overall Business Condition | | Two Wheeler Sales (Retail) | Capacity Utilization | | Three Wheeler Sales (Domestic) | Cost of Borrowing Proxy | | Tractor Sales | Weighted Average Call Money Rate | | Electricity Demand | 91 days T-Bill Rate | | Policy Uncertainty | G-Sec 10 Years Yield | | Global Policy Uncertainty | | | India Policy Uncertainty | | | USA Policy Uncertainty - Three factor model | |

Annex IV : Interpretation of Wavelet Charts Wavelet charts, or wavelet power spectra, are used to analyze signals in both time and frequency domains simultaneously. They help in detecting transient features, periodicities, and localized frequency variations in data. The x-axis of the wavelet charts plots the time whereas the y-axis shows the different periodicities. The wavelet charts plot the phase differences between two series which help to identify the business cycle leading – lagging properties between two economic indicators. The direction of arrows in the phase diagram indicates the relationship between the economic indicators (Chart A2).

|