by Amrita Basu, Akash Raj, Harshita Yadav, Debapriya Saha, Aayushi Khandelwal, Anoop K Suresh, Shromona Ganguly and Atri Mukherjee^ The fiscal position of the Centre and States remained resilient during H1:2025-26. Their receipts were broadly in line with trends observed during H1: 2024-25. Both the Centre and States have demonstrated commitment to prudent fiscal management through containment of revenue expenditure, while maintaining capital expenditure. This has resulted in improvement in the quality of expenditure for the Centre as well as States, which bodes well for medium-term growth prospects and fiscal consolidation. Introduction The Union Budget 2025–26 reaffirmed the Government's commitment to fiscal discipline while fostering inclusive, long-term economic growth in line with the vision of Viksit Bharat. Under the four engines of growth - agriculture, MSMEs, investment, and exports, the Budget contained several measures balancing the socio-economic needs with the long-term structural transformation of the economy. Continuing the thrust on infrastructure development, the Budget 2025-26 provisioned ₹11.2 lakh crore (3.1 per cent of GDP) for capital expenditure. Similarly, the effective capital expenditure1 was budgeted at 4.3 per cent of GDP for 2025-26, higher than 4.0 per cent of GDP as per the revised estimates (RE) for 2024-25. Further, towards incentivising States' capital spending, allocation under the scheme 'Special Assistance to States for Capital Investment' was enhanced from the previous year2. The revenue expenditure of the Centre was budgeted to increase marginally from 10.9 per cent of GDP in 2024-25 (provisional accounts, PA) to 11.0 per cent of GDP in 2025-26 (budget estimates, BE). Overall, the Union Budget aimed at fiscal consolidation, in line with the medium-term target to bring the gross fiscal deficit (GFD) below 4.5 per cent of the GDP by 2025-263. Recognising the importance of analysing sub-annual public finances for efficient fiscal and macro-economic outcomes, this article presents a synoptic view of the half yearly fiscal position for the Centre as well as States. During H1:2025-26, Centre's GFD stood at 36.5 per cent of BE in comparison with 29.4 per cent of BE in H1:2024-25, mainly attributable to robust growth in capital expenditure. On the receipts side, higher collections through non-tax sources and non-debt capital receipts helped in offsetting the moderation of tax revenue for the Centre. In the case of States, the GFD stood at 37.6 per cent of their BE in H1:2025-26, marginally higher than its level recorded during H1:2024-25, mainly attributable to sluggish growth in their revenue receipts. On the expenditure front, States sustained the pace of their revenue expenditure while capital expenditure recorded a marginal growth4,5. The rest of the article is structured as follows: Section II analyses the receipt and expenditure of the Centre and States (at a quarterly frequency) during H1:2025-26. Section III deals with the outcomes in terms of deficit indicators and their financing for the Centre as well as States. Section IV presents estimates on General government (Centre plus States) finances for H1:2025-26. Section V sets out the concluding observations. II. Fiscal Outcome in Q1 and Q2 During H1:2025-26, the Central government collected nearly 50 per cent of its total budgeted receipts, slightly below the collections in the past year. On a year-on-year (y-o-y) basis, total receipts during H1:2025-26 rose by 5.7 per cent. The Centre's total expenditure was contained below 50 per cent of the BE in H1:2025-26, in line with the pattern observed during the past three years (Chart 1a and b). States' total receipts as per cent of BE witnessed moderation in comparison to the previous year (Chart 1a). This was attributable to contraction in grants from Centre6 and slower growth in States' goods and services tax (SGST). On the expenditure side, States have expended 38.2 per cent of their budgeted outlay during H1:2025-26, remaining aligned with their past spending patterns (Chart 1b). a. Receipts The Centre's total receipts (i.e., 'total non-debt receipts') comprise revenue receipts and non-debt capital receipts. During H1:2025-26, the total non-debt receipts of the Central government stood at 49.5 per cent of BE, with the revenue receipts and non-debt capital receipts attaining 49.6 per cent and 45.8 per cent, respectively, of their budgeted target. Primarily on account of lower growth in tax receipts, the Centre's receipts (as per cent of BE) during H1:2025-26 stood marginally below the corresponding figure attained during H1:2024-25. During Q1:2025-26, the y-o-y growth in revenue receipts was slower than that of Q1:2024-25, which was partially offset by the strong growth of non-debt capital receipts7. However, in Q2:2025-26, both revenue receipts and non-debt capital receipts recorded contraction on y-o-y basis (Chart 2a and b).  States' revenue receipts posted modest growth of 6.3 per cent in H1:2025-26, partly due to the weak momentum in SGST collections (Chart 3a). Tax revenue, which accounts for more than two-third (Chart 2a and b). States' revenue receipts posted modest growth of 6.3 per cent in H1:2025-26, partly due to the weak momentum in SGST collections (Chart 3a). Tax revenue, which accounts for more than two-third of revenue receipts exhibited a growth of 7.3 per cent and 11.1 per cent in Q1:2025-26 and Q2:2025-26, respectively. At the same time, States' non-debt capital receipts8 registered robust growth in both the quarters (Chart 3b).  The Centre's direct tax collections grew by 3.0 per cent on y-o-y basis in H1:2025-26, primarily led by an increase of 4.7 per cent in income tax collections while corporate tax collections registered a growth of 1.1 per cent. Similar to the pattern witnessed in H1:2024-25, income tax collections exceeded the corporate tax collections in H1:2025-26, reflecting, inter alia, measures towards improving taxpayers' compliance and broadening the tax base9 (Chart 4a). States' own direct tax collection (comprising land revenue and receipts from stamp duty and registration fees) registered a steady growth driven largely by robust collections from stamp duty (Chart 4b). The Centre's indirect tax collections grew by 2.6 per cent (y-o-y) in H1:2025-2610. This was mainly attributed to growth in GST and excise duties, while revenue from customs declined. In particular, robust GST collections (y-o-y growth of 16.1 per cent) contributed to double-digit growth of 11.3 per cent in total indirect taxes in Q1:2025-26. However, revenue collection contracted on a y-o-y basis across all indirect tax categories in Q2:2025-26, except union excise duties. Overall, in H1:2025-26, the Centre could collect 44.6 per cent of its budgeted indirect taxes as compared to 46.6 per cent during H1:2024-25.  The gross GST collections (Centre plus States) in H1:2025-26 amounted to ₹ 11.9 lakh crore, registering a y-o-y growth of 9.8 per cent (9.5 per cent growth recorded in H1:2024-25), with average monthly collections of ₹2.1 lakh crore and ₹1.9 lakh crore in Q1:2025-26 and Q2:2025-26, respectively (Chart 5). GST revenues continue to draw support from reforms in digital integration, eased compliance processes and rate rationalisation measures undertaken since its inception in 2017 (Box A). In the case of States, the moderation in growth of tax revenues primarily reflected the impact of one-time negative settlement of SGST in April 2025 on collection of States' GST (SGST) (Chart 6a)11. In H1:2025-26, the assignment to States (i.e., tax devolution from the Centre to States) recorded a growth of 14.2 per cent over the corresponding period of the previous year (Chart 6b).

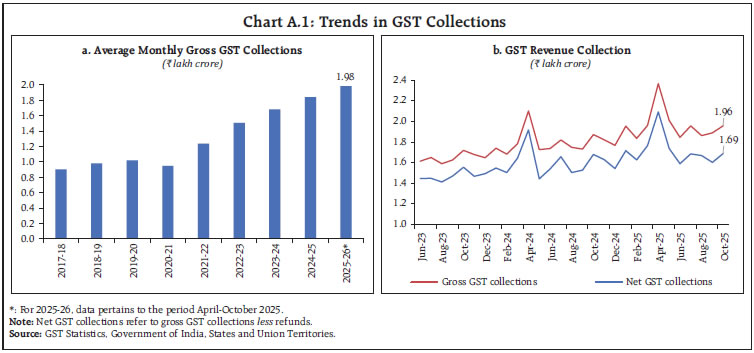

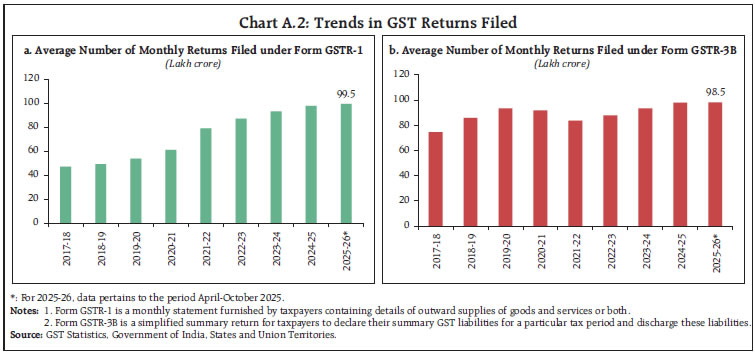

Box A: Tracing Eight Years of GST Reforms in India The goods and services tax (GST), rolled out on July 1, 2017, pan India, had replaced multiple taxes such as central value added tax, central sales tax, state sales tax and octroi. Eight years since its launch, GST has firmly established itself as simpler and more transparent framework, with recent evidence indicating its progressive distributional impact (Mukherjee, 2025). The consistent rise in revenue collections and a growing base of over 1.5 crore active taxpayers stand as testimony to its success. Average monthly GST collections have depicted an increasing trend over the years and stood at ₹1.98 lakh crore for the period April-October 2025, up from ₹1.82 lakh crore attained during April-October 2024. Net GST collections (gross GST collections less refunds) are largely in consonance with the trend in gross GST collections (Chart A.1 and A.2). Since its inception, the GST framework has been continuously evolving towards establishing a streamlined and comprehensive digital infrastructure; enhancing ease of compliance for taxpayers; augmenting a transparent and efficient federal structure; ensuring adherence to reforms by various stakeholders and addressing issues of inverted duty structure12 through rate rationalisation measures. The introduction of a single indirect tax system under GST marked a major digital transformation in India's tax administration by streamlining compliance and creating the foundation for integration of multiple government databases [through the establishment of goods and services tax network (GSTN), the central digital backbone of India's indirect tax ecosystem]. Through the common portal, GSTN supports taxpayers' registration, return filing, payments, and other compliances. The GSTN is a shared infrastructure between the Centre and States which aids transparency in tax collections, thereby promoting fiscal federalism (Government of India, 2019). The e-way bill13 system, introduced in 2018, significantly improved ease of doing business by enabling smooth inter-state and intra-state movement of goods, and reducing check-post paperwork. Subsequently, in September 2019, the GST Council approved the introduction of e-invoicing14, initially applicable to businesses with an annual aggregate turnover of ₹500 crore and above. The threshold has since been reduced to ₹5 crore, making the system more comprehensive. The introduction of e-invoicing has automated and simplified compliance as data from registered invoices is now auto-populated into GST returns such as form GSTR-3B. Furthermore, the system is integrated with the e-way bill portal, enabling faster and more accurate generation of e-way bills.

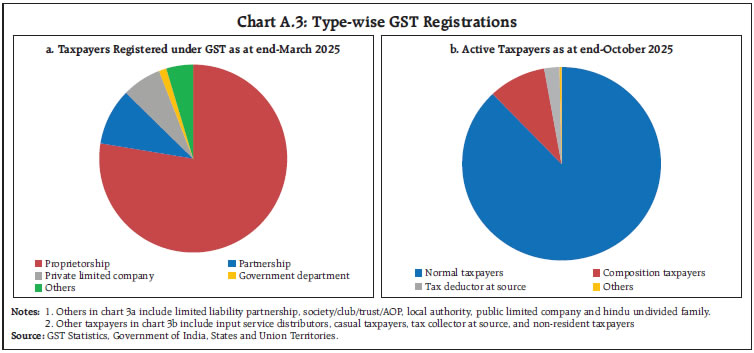

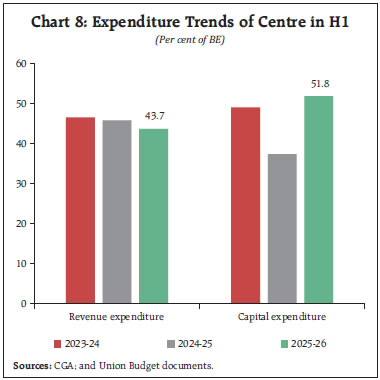

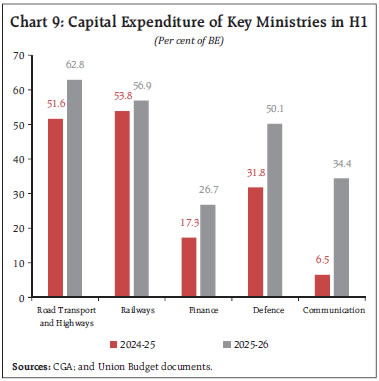

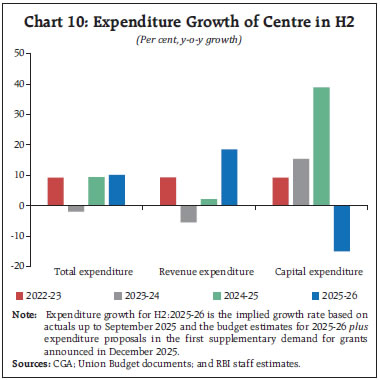

Beyond these, within system improvements, GSTN also connects with other government platforms for specified purposes. For instance, the Indian customs electronic gateway (ICEGATE) and GST systems exchange data necessary for processes such as input tax credit on imports and refund on exports. Similarly, the Udyam registration15 portal for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) draws on PAN/GST linked databases making it easier for enterprises to access government schemes. These digital linkages have reduced data gaps, streamlined coordination between tax and trade systems, and strengthened transparency.  Out of 1.5 crore registered taxpayers under GST16, 77.6 per cent are proprietorships, reflecting predominance of small businesses in the tax base and underscoring the need for simplified compliance mechanisms (Chart A.3a). Ease of compliance for small taxpayers is a key reform undertaken through the GST framework, paving the way for taxpayer-friendly formalisation of the economy. The GST composition scheme was introduced with the objective of easing the compliance burden on small taxpayers by allowing them to file GST returns based on annual turnover rather than individual transactions17. These composition taxpayers constitute about 9.3 per cent of total registered taxpayers under GST as on end-October 2025 (Chart A.3b). Around 6.2 per cent of total composition taxpayers were from the special category States18. Excluding the special category States, number of composition taxpayer, as per cent of total taxpayers was highest in Andhra Pradesh (19.9 per cent), followed by Chhattisgarh (15.8 per cent), Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (15.5 per cent in each case). Cross-country experience suggests that simplified tax regimes, when designed carefully, can potentially reduce compliance costs for small enterprises (Engelschalk and Loeprick, 2015). Over the past eight years, continuous efforts have been made to strengthen the tax system through periodic review of rates by the GST Council for addressing issues such as inverted duty structure, and to ensure due compliance by various stakeholders19. A key milestone in this direction was the reforms announced in September 2025, following the recommendations of the 56th GST Council meeting, which marked a shift from a four-slab rate structure20 to a simplified two-slab GST framework21. The reforms aim to reduce costs for consumers, ease compliance for traders and enhance competitiveness for Indian businesses. Going forward, the resultant rationalisation of GST rates is expected to stimulate demand and support economic activity. To sum up, India's GST framework has evolved as a dynamic and adaptive system, responding to the needs of its key stakeholders, viz., the Centre, States, businesses, and consumers. The reform journey continues with focus on simplification, transparency, and efficiency, aligning the structure progressively with international best practices while preserving the spirit of fiscal cooperation between the Centre and States. References Government of India (2019). The GST Saga: A Story of Extraordinary National Ambition, Ministry of Finance, Government of India. Government of India. Press Information Bureau. Various Press Releases. Engelschalk, M., and Loeprick, J. (2015). MSME Taxation in Transition Economies: Country Experience on the Costs and Benefits of Introducing Special Tax Regimes (Policy Research Working Paper No. 7449). World Bank. Mukherjee, S. (2025). Distributional Effects of GST in India: Evidence from the 2022-23 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey. Economic and Political Weekly. | During H1:2025-26, on the back of higher surplus transfer from the Reserve Bank, the Centre's receipts from non-tax revenue sources recorded strong growth which helped in offsetting the moderation in tax receipts. During Q1:2025-26 and Q2:2025-26, non-tax revenue recorded a y-o-y growth of 33.2 per cent and 20.5 per cent, respectively. The non-debt capital receipts22 recorded robust growth in H1:2025-26 (Chart 7). b. Expenditure In 2025-26, the total expenditure of the Central government is budgeted to grow by 8.8 per cent over 2024-25 (PA) with revenue expenditure and capital expenditure growth budgeted at 9.5 per cent and 6.6 per cent, respectively. In H1:2025-26, revenue expenditure as per cent of BE stood lower than the corresponding period of the previous year, on account of decline in food subsidies. Capital expenditure as per cent of BE was significantly higher than the previous year23, led by growth in loans and advances as well as capital outlay24 (Chart 8).  Capital expenditure of the top 5 ministries, which together comprise nearly 90 per cent of the total budgeted capital expenditure of the Centre for 2025-26, stood at 49.3 per cent of their BE during H1:2025-26, higher than 37.1 per cent of BE during H1:2024-25 (Chart 9). The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, and Ministry of Railways which together comprise 46.8 per cent of the total budgeted capital expenditure of the Centre for 2025-26 have registered a y-o-y growth of 21.7 per cent and 5.6 per cent, respectively, in H1:2025-26. The Union government had also proposed the first batch of supplementary demand for grants for 2025-26 during the winter session of parliament which involves a net cash outgo of ₹41,455 crore. Going forward, in comparison to H2:2024-25, the growth in total expenditure in H2:2025-26 is likely to be moderate, as the Centre aims to adhere to its budgeted deficit target for 2025-26. During H2:2025-26, the growth in revenue expenditure is expected to be higher than the growth recorded in H1:2025-26 to meet the budgeted revenue expenditure target for 2025-26. Since the major portion of budgeted capex for 2024-25 was undertaken during H2:2024-25, the capex growth during H2:2025-26 is likely to slow down on a year-on-year basis reflecting the base effect (Chart 10).

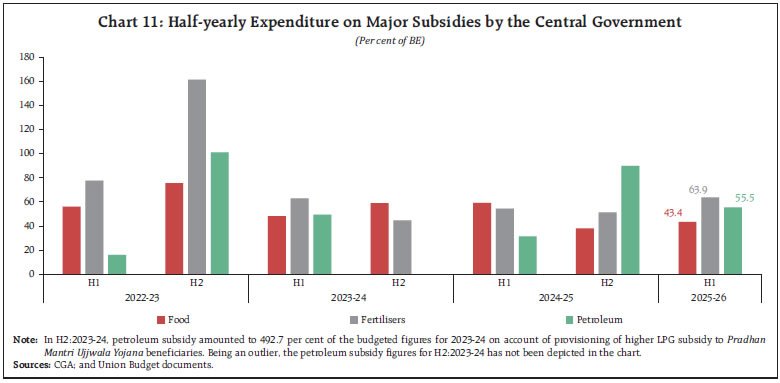

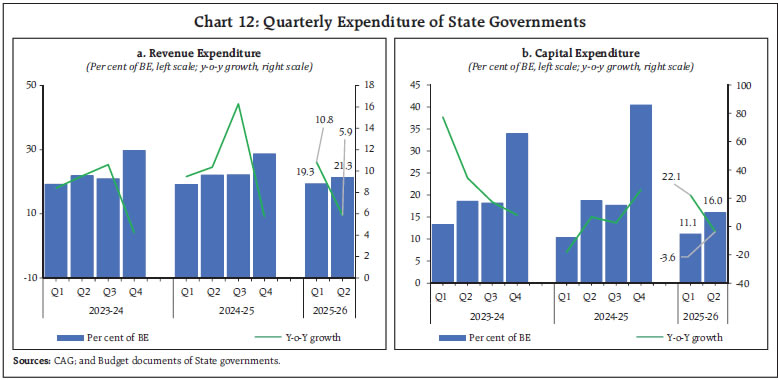

The outgo of the Central government on major subsidies, comprising food, fuel and fertilisers stood at 52.8 per cent of BE in H1:2025-26 as compared to 56.3 per cent of BE in H1:2024-25. This decline in major subsidies is primarily attributable to contraction in food subsidy. Fertiliser subsidy stood at 63.9 per cent of its budgeted amount in H1:2025-26 due to, inter alia, rising international prices of urea and nutrient based subsidy25. Petroleum subsidy, primarily comprising subsidy spending under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana26 stood at 55.5 per cent of its budgeted amount during H1:2025-26 (Chart 11). States' revenue expenditure remained healthy with y-o-y growth in H1:2025-26 (Chart 12a). Keeping in line with the spending behaviour of the previous year, States have exhausted 40.6 per cent of their budgeted revenue expenditure in H1:2025-26. Meanwhile, capital expenditure grew at 5.5 per cent during H1:2025-26, witnessing strong growth in Q1 on account of a lower base, while registering a contraction in Q2 (Chart 12b). Going forward, capital expenditure is likely to gather momentum, through Centre's interest free loan scheme for capital investment and the typical year-end spending concentration (Box B).

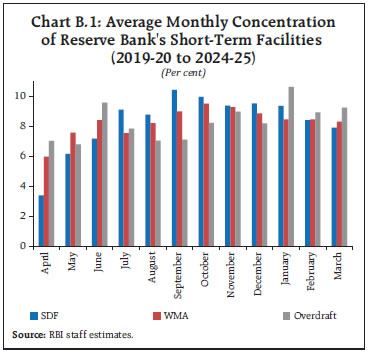

Box B: Seasonal Concentration of Fiscal Aggregates across Subnational Governments The seasonal concentration of fiscal aggregates is a central aspect of cash flow management across Indian States, often shaping their short-term borrowing needs. When the timing of revenue receipts and expenditure commitments diverges, States face temporary gaps that must be bridged to maintain payment continuity. Accordingly, States rely on their intermediate treasury balances before turning to Reserve Bank of India's liquidity facilities27, namely the special drawing facility (SDF), ways and means advances (WMA), and overdraft (OD). Between 2019-20 to 2024-25, there has been a steady rise in SDF usage till September. WMA usage peaks in October ahead of festive quarter, while Overdraft usage gathers pace in January-March, aligning with early stages of the year-end spending cycle, when expenditures typically record their year-end peak (Chart B.1).

To analyse how the mismatch between receipts and expenditure shapes States' short-term liquidity needs, monthly concentration of States' revenue receipts along with its major components such as tax devolution, States' goods and services tax (SGST) and grants from the Centre are considered for the period 2019-2025 (Chart B.2a). The overall pattern reveals a clear year-end concentration in aggregate receipts, reflecting the influence of both administrative and cyclical factors. Within components, the tax devolution from the Centre peaks in March, coinciding with the year-end settlement of Central tax devolution and advance tax inflow. This arises because Centre's corporate tax and income tax collections are themselves clustered around advance payment schedule and finalisation of accounts (Srivastava and Trehan, 2018; Srivastava et al., 2025). Grants-in-aid record a distinct local peak28 in June, followed by milder peaks in September and December, and a pronounced yearend surge in March, reflecting the typical bunching of scheme-related transfers. In contrast, SGST collections, being closely linked to consumption and economic activity, show relatively stable inflows with mild festive-season peaks. The month-wise expenditure pattern of States displays a distinct back-loaded concentration (Chart B.2b) with revenue expenditure remaining relatively stable, as a large part of it is committed in nature. In April and May, overall spending activity remains subdued as observed across various States. From June onwards, expenditure begins to pick up. State government expenditure witness year-end surge in February and March when departments expedite project execution, following the flow of funds from schemes under Grants and departments also clear pending bills to avoid lapse of funds. The sharp bunching of spending in these final months, especially in capital expenditure, intensifies liquidity pressures, often compelling States to rely on short-term borrowing. With regular cheaper borrowing facilities such as SDF and WMA nearing exhaustion, several States resort to overdraft mechanisms to bridge temporary cash gaps. This reinforces the need for smoother intra-year expenditure calibration to reduce reliance on temporary borrowing facilities. References Srivastava, D. K., and Trehan, R. (2018). Managing Central Government Finances: Asymmetric Seasonality in Receipts and Expenditures. Global Business Review, 19(5), 1322-1344. Srivastava, D. K., Bharadwaj, M., Kapur, T., and Trehan, R. (2025). Seasonal Concentration of Fiscal Aggregates: Case Study of India. Modern Economy, 16(9). | III. Fiscal Deficit and its Financing Central Government a. Fiscal Deficit The Central government budgeted for a GFD of 4.4 per cent of GDP in 2025-26 as compared with 4.8 per cent in 2024-25 (PA), in line with the glide path to achieve medium term GFD target of below 4.5 per cent of GDP by 2025-26. While GFD-GDP ratio in Q1:2025-26 was higher than the corresponding quarter of the previous year, the trend reversed in Q2:2025-26. During H1:2025-26, the GFD of the Central government stood at 36.5 per cent of the BE, higher than 29.4 per cent recorded during H1:2024-25, reflecting higher growth in Centre's capital expenditure (Chart 13a and b). b. Financing of GFD In H1:2025-26 (up to September 26, 2025), the Central government completed 48.2 per cent of the budgeted net market borrowings for 2025-26 (as against 43.9 per cent in the corresponding period last year), which financed a major chunk of its GFD. State Government a. Fiscal Deficit States budgeted a consolidated GFD of 3.3 per cent of GDP for 2025-26, lower than 3.5 per cent in 2024-25 (RE). States have exhausted a marginally higher proportion of their budgeted GFD in Q1:2025-26 and Q2:2025-26, respectively, as compared to Q1 and Q2 of 2024-25. Correspondingly, the fiscal space available to States for H2:2025-26 has slightly reduced to 62.4 per cent of their budgeted GFD, as against 62.9 per cent available during H2:2024-25 (Chart 14a and b). b. Financing of GFD States' net market borrowings during H1:2025-26 registered a growth of 22.3 per cent over the corresponding period of the previous year. During this period, States utilised 35.9 per cent of their budgeted net market borrowings, up from 32.1 per cent in the same period of 2024-25. Seventeen States utilised a higher proportion of their budgeted net borrowings as compared to the corresponding period of the previous year (Chart 15a and b). Gross market borrowings increased by 21.0 per cent over the previous year, representing 37.5 per cent of the budgeted amount. The financial accommodation availed by States through various facilities provided by the Reserve Bank increased by 52.7 per cent in H1:2025-26 over the corresponding period of the previous year. The ways and means advances (WMA) limits were revised effective from July 1, 2024. The aggregate WMA limit for States/UTs now stands at ₹60,118 crore, an increase of 27.9 per cent over the earlier limit of ₹47,010 crore. States utilised 8.1 per cent of the permissible WMA limit in Q1:2025-26 and 10.6 per cent in Q2:2025-26. The average utilisation by States under all the three facilities viz., special drawing facility, ways and means advances and overdraft rose during H1:2025-26 over the corresponding period of the previous year (Chart 16a and b).

Quality of Expenditure – Centre and States The revenue expenditure to capital outlay (RECO) ratio of the Centre declined to 3.7 in H1:2025-26 from 4.7, a year ago (i.e., in H1:2024-25), lowest in more than a decade29, reflecting the continued impetus of the government in improving the quality of its expenditure (Chart 17a). Similarly, in the case of States, the expenditure quality has been improving as reflected in declining RECO ratio in H1:2025-26 compared to the previous year (Chart 17b). IV. General Government Finances In continuation of the effort to provide timely fiscal data on the general government, the quarterly fiscal position of the general government has been compiled till Q2:2025-26. In Q1:2025-26, the increase in combined expenditure of the Centre and States, mainly on account of higher growth in capital expenditure, resulted in an uptick of GFD. However, in Q2:2025-26, the GFD as percent of GDP moderated on a y-o-y basis, primarily attributable to the containment of revenue expenditure (Chart 18).

V. Conclusion During H1:2025-26, moderation in tax receipts was partially offset by robust non-tax revenue as well as non-debt capital receipts of the Centre. Overall, the Centre has collected almost half of its budgeted revenue in H1:2025-26 while containing its expenditure to less than half of the budget estimates for 2025-26. This augurs well for the Centre to meet its GFD target of 4.4 per cent of GDP for 2025-26. In the case of States, their GFD as a per cent of BE during H1:2025-26 was only marginally higher than that of H1:2024-25 mainly attributable to lower growth in their revenue receipts. On the expenditure front, the States sustained their revenue expenditure while maintaining capex. Going forward, States need to maintain their capex momentum alongside fiscal consolidation to ensure overall stability.

Appendix Tables | Table I: Budgetary Position of the Central Government during April-September | | Item | (₹ thousand crore) | (Per cent) | | Actuals: H1 | Budget Estimates (BE) | Per cent of BE | Y-o-Y Growth | | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | | 1. Revenue Receipts | 1,622.4 | 1,695.4 | 3,129.2 | 3,420.4 | 51.8 | 49.6 | 16.1 | 4.5 | | (i) Net Tax Revenue | 1,265.2 | 1,229.4 | 2,583.5 | 2,837.4 | 49.0 | 43.3 | 9.0 | -2.8 | | (ii) Non-Tax Revenue | 357.2 | 466.1 | 545.7 | 583.0 | 65.5 | 79.9 | 50.9 | 30.5 | | (iii) Interest Receipts | 20.4 | 18.0 | 38.2 | 47.7 | 53.3 | 37.7 | 17.6 | -11.5 | | 2. Non-Debt Capital Receipts | 14.6 | 34.8 | 78.0 | 76.0 | 18.7 | 45.8 | -27.6 | 138.1 | | (i) Recovery of Loans | 11.4 | 11.4 | 28.0 | 29.0 | 40.8 | 39.1 | -13.5 | -0.7 | | (ii) Miscellaneous Capital Receipts | 3.2 | 23.4 | 50.0 | 47.0 | 6.3 | 49.8 | -54.4 | 639.4 | | 3. Total Receipts (1+2) | 1,637.0 | 1,730.2 | 3,207.2 | 3,496.4 | 51.0 | 49.5 | 15.5 | 5.7 | | 4. Revenue Expenditure | 1,696.5 | 1,722.6 | 3,709.4 | 3,944.3 | 45.7 | 43.7 | 4.2 | 1.5 | | (i) Interest Payments | 515.0 | 578.2 | 1,162.9 | 1,276.3 | 44.3 | 45.3 | 6.3 | 12.3 | | 5. Capital Expenditure | 415.0 | 580.7 | 1,111.1 | 1,121.1 | 37.3 | 51.8 | -15.4 | 40.0 | | (i) Loans and Advances | 55.4 | 118.9 | 192.4 | 225.8 | 28.8 | 52.6 | -25.9 | 114.6 | | (ii) Capital Outlay | 359.6 | 461.9 | 918.7 | 895.2 | 39.1 | 51.6 | -13.5 | 28.5 | | 6. Total Expenditure (4 + 5) | 2,111.5 | 2,303.3 | 4,820.5 | 5,065.3 | 43.8 | 45.5 | -0.4 | 9.1 | | 7. Revenue Deficit (4 - 1) | 74.2 | 27.1 | 580.2 | 523.8 | 12.8 | 5.2 | -68.0 | -63.4 | | 8. Fiscal Deficit (6 - 3) | 474.5 | 573.1 | 1,613.3 | 1,568.9 | 29.4 | 36.5 | -32.4 | 20.8 | | 9. Gross Primary Deficit {8 - 4(i)} | -40.5 | -5.1 | 450.4 | 292.6 | -9.0 | -1.7 | -118.6 | 87.5 | Note: Negative primary deficit indicates primary surplus.

Sources: Controller General of Accounts; and Union Budget Documents. |

| Table II: Quarterly Position of the Central Government Finances | | Item | (₹ thousand crore) | (Per cent) | | Actuals | Per cent of Budget Estimates | Y-o-Y Growth | | Q1 | Q2 | Q1 | Q2 | 2025-26 | | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | Q1 | Q2 | | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | | 1. Revenue Receipts | 829.7 | 913.4 | 792.7 | 782.1 | 26.5 | 26.7 | 25.3 | 22.9 | 10.1 | -1.3 | | (i) Net Tax Revenue | 549.6 | 540.3 | 715.5 | 689.1 | 21.3 | 19.0 | 27.7 | 24.3 | -1.7 | -3.7 | | (ii) Non-Tax Revenue | 280.0 | 373.1 | 77.2 | 93.0 | 51.3 | 64.0 | 14.1 | 16.0 | 33.2 | 20.5 | | (iii) Interest Receipts | 11.7 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 30.6 | 20.3 | 22.6 | 17.4 | -17.2 | -3.8 | | 2. Non-Debt Capital Receipts | 4.5 | 28.0 | 10.1 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 36.9 | 12.9 | 8.9 | 519.9 | -33.0 | | (i) Recovery of Loans | 4.5 | 5.4 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 16.1 | 18.6 | 24.7 | 20.5 | 19.5 | -13.9 | | (ii) Miscellaneous Capital Receipts | 0.0 | 22.6 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 48.1 | 6.3 | 1.7 | 5,65,475.0 | -74.9 | | 3. Total Receipts (1+2) | 834.2 | 941.4 | 802.8 | 788.8 | 26.0 | 26.9 | 25.0 | 22.6 | 12.9 | -1.7 | | 4. Revenue Expenditure | 788.9 | 947.0 | 907.7 | 775.6 | 21.3 | 24.0 | 24.5 | 19.7 | 20.0 | -14.6 | | (i) Interest Payments | 264.1 | 386.0 | 251.0 | 192.1 | 22.7 | 30.2 | 21.6 | 15.1 | 46.2 | -23.4 | | 5. Capital Expenditure | 181.1 | 275.1 | 233.9 | 305.6 | 16.3 | 24.5 | 21.1 | 27.3 | 52.0 | 30.7 | | (i) Loans and Advances | 30.0 | 69.8 | 25.4 | 49.0 | 15.6 | 30.9 | 13.2 | 21.7 | 132.7 | 93.2 | | (ii) Capital Outlay | 151.0 | 205.3 | 208.5 | 256.6 | 16.4 | 22.9 | 22.7 | 28.7 | 35.9 | 23.0 | | 6. Total Expenditure (4 + 5) | 969.9 | 1,222.1 | 1,141.6 | 1081.2 | 20.1 | 24.1 | 23.7 | 21.3 | 26.0 | -5.3 | | 7. Revenue Deficit (4 - 1) | -40.8 | 33.6 | 115.0 | -6.5 | -7.0 | 6.4 | 19.8 | -1.2 | 182.4 | -105.6 | | 8. Fiscal Deficit (6 - 3) | 135.7 | 280.7 | 338.8 | 292.4 | 8.4 | 17.9 | 21.0 | 18.6 | 106.9 | -13.7 | | 9. Gross Primary Deficit {8 - 4(i)} | -128.3 | -105.3 | 87.8 | 100.2 | -28.5 | -36.0 | 19.5 | 34.3 | 17.9 | 14.1 | Note: Negative revenue deficit and primary deficit indicate revenue surplus and primary surplus, respectively.

Sources: Controller General of Accounts; and Union Budget Documents. |

| Table III: Budgetary Position of the State Governments during April-September 2025 | | Item | (₹ thousand crore) | (Per cent) | | Actuals: H1 | Budget Estimates | Per cent of BE | Y-o-Y Growth | | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | | 1. Revenue Receipts | 1,682.8 | 1,788.5 | 4,231.3 | 4,636.0 | 39.8 | 38.6 | 7.2 | 6.3 | | 1.1. Tax Revenue | 1,395.3 | 1,523.6 | 3,244.7 | 3,605.8 | 43.0 | 42.3 | 12.1 | 9.2 | | 1.2. Non-Tax Revenue | 123.3 | 133.7 | 372.1 | 411.1 | 33.1 | 32.5 | -7.5 | 8.4 | | 1.3. Grants-in-aid and Contributions | 164.2 | 131.3 | 614.6 | 619.1 | 26.7 | 21.2 | -14.2 | -20.1 | | 2. Non-Debt Capital Receipts | 2.8 | 6.0 | 43.7 | 48.9 | 6.3 | 12.2 | -30.9 | 116.6 | | 2.1. Recovery of Loans and Advances | 2.7 | 5.9 | 20.6 | 24.0 | 13.1 | 24.7 | -26.0 | 119.9 | | 2.2. Other Miscellaneous Capital Receipts | 0.1 | 0.0 | 23.1 | 24.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | -82.1 | -27.9 | | 3. Total Receipts | 1,685.6 | 1,794.5 | 4,275.1 | 4,684.9 | 39.4 | 38.3 | 7.1 | 6.5 | | 4. Revenue Expenditure | 1,780.1 | 1,925.8 | 4,326.4 | 4,740.2 | 41.1 | 40.6 | 10.0 | 8.2 | | 4.1 Interest Payments | 230.6 | 257.9 | 527.8 | 586.1 | 43.7 | 44.0 | 11.8 | 11.8 | | 5. Capital Expenditure | 269.9 | 284.7 | 931.3 | 1,051.4 | 29.0 | 27.1 | -3.7 | 5.5 | | 5.1 Capital Outlay | 233.9 | 255.4 | 850.9 | 972.2 | 27.5 | 26.3 | -8.7 | 9.2 | | 6. Total Expenditure | 2,050.1 | 2,210.5 | 5,257.7 | 5,791.6 | 39.0 | 38.2 | 7.9 | 7.8 | | 7. Revenue Deficit (4-1) | 97.3 | 137.3 | 95.0 | 104.2 | 102.4 | 131.7 | 98.2 | 41.0 | | 8. Fiscal Deficit (6-3) | 364.5 | 416.0 | 982.6 | 1,106.7 | 37.1 | 37.6 | 12.1 | 14.1 | | 9. Gross Primary Deficit (8 - 4.1) | 133.9 | 158.1 | 454.8 | 520.6 | 29.4 | 30.4 | 12.4 | 18.1 | Note: Data Pertains to 23 States.

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General of India. |

| Table IV: Quarterly Position of State Government Finances | | Item | (₹ thousand crore) | (Per cent) | | Actuals | Per cent of BE | Y-o-Y Growth | | Q1 | Q2 | Q1 | Q2 | 2025-26 | | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | Q1 | Q2 | | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | | 1. Revenue Receipts | 820.4 | 874.3 | 862.4 | 914.2 | 19.4 | 18.9 | 20.4 | 19.7 | 6.6 | 6.0 | | 1.1. Tax Revenue | 701.2 | 752.5 | 694.0 | 771.0 | 21.6 | 20.9 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 7.3 | 11.1 | | 1.2. Non-Tax Revenue | 62.2 | 64.9 | 61.1 | 68.8 | 16.7 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 4.4 | 12.5 | | 1.3. Grants-in-aid and Contributions | 57.0 | 56.8 | 107.2 | 74.5 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 17.4 | 12.0 | -0.4 | -30.5 | | 2. Non-Debt Capital Receipts | 1.4 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 127.5 | 106.0 | | 2.1. Recovery of Loans and Advances | 1.3 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 6.4 | 12.7 | 6.6 | 11.9 | 130.4 | 109.8 | | 2.2. Other Miscellaneous Capital Receipts | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -6.8 | -45.6 | | 3. Total Receipts | 821.8 | 877.4 | 863.8 | 917.1 | 19.2 | 18.7 | 20.2 | 19.6 | 6.8 | 6.2 | | 4. Revenue Expenditure | 827.1 | 916.8 | 953.0 | 1,009.0 | 19.1 | 19.3 | 22.0 | 21.3 | 10.8 | 5.9 | | 4.1 Interest Payments | 101.0 | 106.3 | 129.7 | 151.5 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 24.6 | 25.9 | 5.3 | 16.9 | | 5. Capital Expenditure | 95.7 | 116.8 | 174.3 | 167.9 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 18.7 | 16.0 | 22.1 | -3.6 | | 5.1. Capital Outlay | 82.6 | 103.5 | 151.3 | 151.8 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 17.8 | 15.6 | 25.3 | 0.3 | | 6. Total Expenditure | 922.8 | 1,033.6 | 1127.3 | 1,176.9 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 12.0 | 4.4 | | 7. Revenue Deficit | 6.7 | 42.5 | 90.7 | 94.8 | 7.0 | 40.8 | 95.4 | 91.0 | 537.4 | 4.5 | | 8. Fiscal Deficit (6-3) | 101.0 | 156.2 | 263.5 | 259.8 | 10.3 | 14.1 | 26.8 | 23.5 | 54.7 | -1.4 | | 9. Gross Primary Deficit (8 - 4.1) | 0.0 | 49.9 | 133.9 | 108.3 | 0.0 | 9.6 | 29.4 | 20.8 | - | -19.1 | Note: Data pertains to 23 States.

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General of India. |

|