by Indrajit Roy and K. M. Neelima^ Nowcasting has become a useful tool for policymakers especially for macroeconomic variables like GDP for which data are released with considerable lags. A novel two-step approach for nowcasting India’s GDP is proposed using twenty-two high frequency indicators wherein the first factor is obtained based on the strength of each indicator in relation to GDP and a second factor is built from the residual information of the indicators which are otherwise generally discarded. The empirical exercise reveals that incorporating secondary information from residuals greatly improves accuracy of nowcasting GDP. Introduction Following overlapping shocks—COVID-19 pandemic, multiple and prolonged geopolitical conflicts, surge in inflation across the globe—policy makers, especially central banks, had their task cut out to prop up the economy while managing the ramifications emanating from the different shocks. With new challenges emerging often, associated uncertainty has made it difficult to assess the current and future outlook of the economy. For policymakers, having a clear picture of the underlying state of the economy is critical for undertaking appropriate policy responses. Gross domestic product (GDP) can be considered as the most authoritative measure of economic activity (Proietti, Giovannelli, Ricchi, & Citton, 2021). The national accounts provide a comprehensive view of the economy but are released with considerable lags. Therefore, forecasting macroeconomic indicators, especially GDP, is a necessity for optimal policy response and reliable short-term forecasts are generally high in demand when the economic environment is uncertain (Hindrayanto, Koopman, & Winter, 2016). Central banks and other policy makers track certain high frequency indicators to gauge the underlying state of the economy. However, divergence among various indicators make it difficult to accurately assess the extant condition of the economy. Essentially, separating meaningful information from noise is a humongous task and several techniques ranging from detecting business cycle turning points and constructing indexes of economic activity to forecasting comprehensive macroeconomic measures of the state of the economy with formal models and judgment have been applied to tackle it (Bok et al., 2017). Summarising the information content available from different indicators using modelling techniques in recent periods into a composite index, or nowcasting, was thus developed to respond to the policymakers’ need for a reliable indicator in advance of the release of the relevant macroeconomic variable. Hence, an important feature of nowcasting is the extraction of all the available information from a large information set and it provides an early estimate of the reference series before it is published. Most of the nowcast models generally reduces dimensions of large number of selected indicators into few factors. This can be done by dynamic factor modelling (DFM) or even using weighted average of indicators where weights are correlation of indicators with the target. High frequency indicators are generally selected for nowcasting based on convenience and timely availability of the indicators. As a result, for nowcasting a composite target, for example, GDP or gross value added (GVA), a sub-sector of the target may be over-represented by inclusion of greater number of selected proxy indicators vis-à-vis other sectors. Thus, factor modelling, which essentially reduces the dimensionality of large number of indicators and produces few common factors, is influenced by indicator selection bias as the chosen factor may identify the co-movement of the selected indicators very well, while not necessarily capturing the relationship with the target series truly. It may also be the case that in DFM, information contents of the selected indicators are not completely utilised as only the first few latent factors are chosen based on eigenvalues, and other factors with lower eigen values are ignored which, in turn, may be having strong correlation with the reference series but are not strongly correlated with majority of other indicators in the information set. In this article, an attempt has been made to nowcast India’s GDP using a two-step approach (two-stage maximum information model - TSMIM) wherein in the first stage a primary composite index (PCI) is computed, by linearly combining these indicators based on the strength of their association (correlation) with the targeted series. PCI may also be computed using DFM. In the second stage, to further extract relevant information from the indicators beyond what is already extracted and aggregated in PCI, each indicator is regressed on the PCI and the corresponding residuals are estimated which are, in turn, aggregated based on their association with the target series to form a secondary composite index (SCI). PCI and SCI are then jointly used to nowcast GDP. The novelty of our new approach lies in a) giving more weightage to those indicators that are correlated with the target series rather than co-movement of the indicators among themselves, and b) maximising information by utilising information which are discarded by the conventional modelling process by creating a secondary information source based on residuals. To compare the nowcasting performance of TSMIM, following four models are considered: -

TSMIM-1 with PCI as weighted average of chosen indicators and SCI as weighted average of residuals extracted from these indicators which are not part of PCI. -

Using only PCI as weighted average of chosen indicators and no SCI. -

TSMIM-2 with DFM based factor as the PCI and SCI as weighted average of residuals extracted from the indicators which are not part of DFM. -

Benchmark DFM. For ascertaining the efficiency of nowcasting exercise, out-of-sample prediction method is undertaken for the period Q4:2022-23-Q4:2024-25. This empirical exercise reveals a relatively improved performance of the new framework models (TSMIM-1 and TSMIM-2) when compared with one-step models (models b and d). We further check for robustness of the approach on real GVA growth and find that the new models demonstrate improved performance over DFM for GVA as well. Rest of the paper is organised as follows: brief literature review is undertaken in section II and section III elaborates the methodology and data used. Section IV discusses the results and the evaluation of the new model and section V concludes. II. Literature Review There are many nowcasting techniques available in the literature. Among these techniques, principal component analysis/dynamic factor models (PCA/DFM) to nowcast low frequency macroeconomic variable such as GDP is popular. PCA, which is the core of the DFM model for nowcasting, transforms original information set into uncorrelated factors, which are the weighted linear combination of constituent indicators. Thus, it resolves both the curse of dimensionality issue as well as the multicollinearity issues. A more prevalent approach of nowcasting currently is DFM. This method is widely used in summarising co-moving indicators, that cover the broad spectrum of economic activities in an economy, as latent factor(s) separated from idiosyncratic and measurement errors and can be interpreted as underlying state of the economy. In the model, a state-space framework is followed which involves a measurement equation linking the vector of observed indicators to a vector of unobserved state variables and a transition equation which specifies the dynamics of the unobserved state variables. Stock and Watson (1989) pioneered the use of factor models for construction of business cycle indexes. Giannone et al. (2008), introduced factor models for nowcasting in a mixed frequency setup and the nowcasting model was developed using monthly data on a large set of high-frequency indicators. Many central banks have developed nowcasting methods to get a fair idea about how the economy is performing in a given quarter much before the official data release. The nowcasting model of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York uses a dynamic factor model that generates estimates of current quarter GDP growth at a weekly frequency (Almuzara, Baker, O’Keeffe, & Sbordone, 2023). On the other hand, The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow model is a nowcasting model that uses a bridge equation approach that relates GDP subcomponents to monthly source data with factor model and Bayesian vector autoregression techniques (Higgins, 2014). In India too, several studies have been undertaken on nowcasting GDP as GDP data are released by the National Statistics Office (NSO) with a lag of two months. Bhattacharya et al. (2011) finds that a small set of pre-selected key monthly indicators, serving as proxies for the various sub-sectors of the economy perform satisfactorily in predicting current quarter growth. Several studies in India use DFM for nowcasting (Roy, Sanyal, & Ghosh, 2016; Bragoli & Fosten, 2017; Iyer & Sen Gupta, 2019; Kumar, 2020; Bhadury, Ghosh, & Kumar, 2021; Prakash, Bhowmick, & Thakur, 2022; Kaustubh & Ranjan, 2025). However, Matheson (2011) finds that forecasting performance of DFM for Australia and India was not on par with other countries which may be attributable to large data revisions of indicators in these countries. Bayesian vector autoregression (Iyer & Sen Gupta, 2019) and machine learning approaches (Ghosh & Ranjan, 2023) are also used for nowcasting. In DFM, the factors are linear combination of constituent indicators. However, as only first few components are chosen (with eigenvalue more than 1), and other factors with lower eigen values are ignored, there is an inherent loss of information since they might have good association with the reference series. It is likely that the factors with lower eigen value are those factors which are dominated (with higher loading/share) by indicators which may have strong correlation with the reference series but are not strongly correlated with majority of other indicators in the information set. As a result, there may be factors, which possess relevant information to explain variation in the reference series, but is discarded due to low eigen value which result in suboptimal performance in explaining the reference series. Our paper focuses on this aspect by obtaining additional information set from residuals which may help improve the nowcasting technique. III. Methodology and Data III.1 Two-stage Maximum Information Model (TSMIM) Following Roy and Narayanan (2018), we use a two-step process to construct a two-stage maximum information model (TSMIM). When the target series is of quarterly frequency and indicators are of monthly frequency, the indicators are averaged over three months to get quarterly series1. These quarterly indicators are then standardised by subtracting their mean and dividing by standard deviation. Let Xit and Yt denote ith indicator and the reference series at time t, respectively, where i = 1, 2….n; t=1, 2….T. Corresponding standardised series, xit and yt are defined as: In the first step, we calculate correlation coefficient (ρi) of each indicator with the target series. Then primary composite index (PCI) is defined as follows: Essentially, PCI is a certain linear combination of selected indicators, and it contains common information of interest pertaining to association of these selected indicators with the reference series. In the second step, we look for additional information in the information set beyond PCI. Certain components of the reference series may be under-represented or over-represented by the indicators selected, thus PCI may be influenced by this biased selection. We start with regressing each of the indicator on the PCI and estimating the corresponding residuals as follows: Notably, this additional information set is built from the residual information of the n-indicators which are not part of PCI. Therefore, PCI and SCI are two composite indices of coincident indicators for the reference series constructed out of many indicators and are linear combination of indicators. Also, by construction, PCIt and SCIt are uncorrelated, therefore, these can be used together to explain Yt without any multicollinearity issue. Nowcasted value of the reference series can be obtained as follows: Together, PCI and SCI can explain the reference series much better than PCI alone. The benchmark DFM model is described in Annex A. III.2 Data For nowcasting a reference series, a set of indicators is chosen based on the strength of their connection or relationship (correlation coefficients, visual inspection from scatter plot) with the reference series. We initially followed Kumar (2020) for variable selection as the 27 indicators in the model were based on whether they are tracked by NSO, their correlation with GDP, and availability of time series data. However, we find that five variables viz., US PMI, non-food credit, tractor sales, CPI excluding food and beverage and money supply were not significantly correlated with GDP and were dropped from the model (Annex Table A1). We use a set of 22 indicators2 which are significantly correlated with GDP (Table 1). | Table 1: List of Indicators | | Industry | Services | Global | Miscellaneous | | Index of Industrial Production | Domestic air passenger traffic | US Industrial Production | Gross taxes | | Automobile sales | Domestic air cargo traffic | Baltic Dry Index | JobSpeak Index | | Non-oil exports | Port cargo traffic | OECD Composite Leading Indicator | Crude price (average of Brent, Dubai and WTI) | | Non-oil-non-gold imports | Railway freight | US payrolls | | | Purchasing Managers’ Index - Mfg. | Foreign tourist arrivals | | | | Power supply | Purchasing Managers’ Index - Services | | | | | Fuel consumption | | | | | IIP Cement | | | | | Steel consumption | | | | Source: Authors’ compilation. | Broadly, these indicators cover major segments of domestic activity- directly or indirectly. The four blocks of data are a) industry; b) services, c) global and d) miscellaneous. The data includes a) hard data on economic activity for example, index of industrial production, automobile sales, port cargo traffic, domestic air cargo traffic etc., b) surveys representing economic activity like PMI, c) trade such as non-oil exports, non-oil imports, Baltic Dry Index etc., d) employment conditions as captured by JobSpeak Index and e) global conditions as captured by OECD composite leading indicator, US payroll data and US industrial production. All indicators are in year-on-year terms. The nowcasting exercise is undertaken separately for each quarter for the period Q4:2022-23 – Q4:2024-25 using data spanning Q1:2011-12 – Q4:2024-25. IV. Results: Nowcasting of India’s GDP and Model Evaluation Strength of association, in terms of correlation coefficients, of selected indicators with the chosen target series viz., GDP is given in Annex Table A1. Estimates of equation (3) for deriving second information set and equation (4) for correlation of residuals with GDP are reported in Annex Tables A2 and A3, respectively. IV.1 Model Evaluation To assess the performance of the proposed model, empirical exercise to nowcast real GDP using the following four models were undertaken: -

TSMIM-1 with PCI as weighted average of indicators and SCI as weighted average of residuals extracted from the indicators which are not part of PCI. -

Using only PCI as weighted average of chosen indicators and no SCI. -

TSMIM-2 with DFM based factor as the PCI and SCI as weighted average of residuals extracted from the indicators which are not part of DFM. -

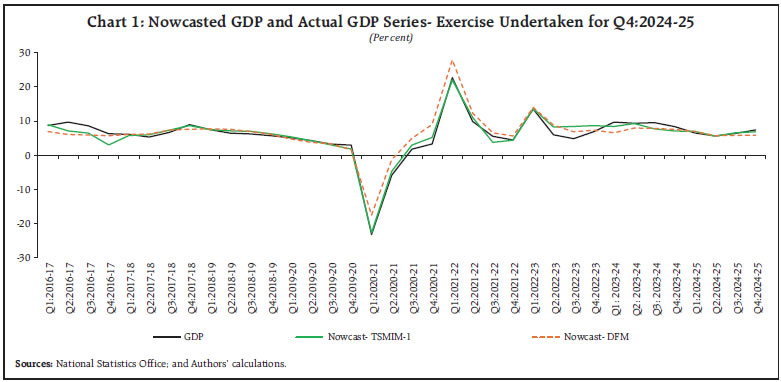

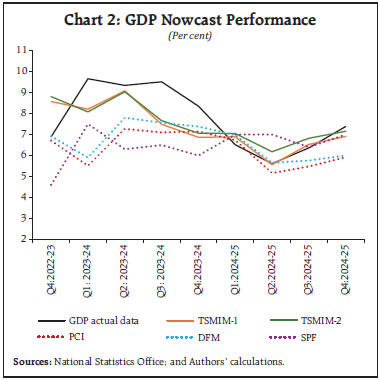

Benchmark DFM. The results were also compared with median forecasts of survey of professional forecasters (SPF). The in-sample model fit using results of the nowcast exercise undertaken for the latest quarter, viz., Q4:2024-25 is given below. The coefficients—PCI, SCI and dynamic factor (DF)— are significant suggesting that these factors can explain real GDP growth. Further, the different models for nowcasting GDP show that the in-sample fit of (model a) TSMIM-1, and (model c) TSMIM-2 are better than that of using benchmark DFM model (model d), and using only PCI (model b) on the basis of R-square. Using a single factor - DF or PCI - explains around 85 per cent of the variability of GDP (model b and model d) while using two factors together explain 94 per cent of the variability of GDP suggestive of superior performance of using secondary factor in both cases (Table 2). Visual presentation of nowcasted GDP series using both DFM and TSMIM-1 undertaken for the quarter Q4:2024-25 vis-à-vis actual GDP is provided in Chart 1. Nowcasted GDP using TSMIM-1 was found to be closely following the target variable. The results for out-of-sample nowcasts for the study period comparing the model estimates vis-à-vis the quarterly estimates of GDP data released by MOSPI on May 30, 2025 is given in Table 3. The nowcast performance is also compared against projections of the latest round of the survey of professional forecasters (SPF). We calculate error (actual-nowcast) for each quarter and average root mean squared error (RMSE) for all models for the period under study. | Table 2: GDP Regression Estimates | Dependent Variable: GDP

Method: Least Squares

Sample (adjusted): 2012Q2-2024Q4 | | Variable | TSMIM-1

(model a) | PCI

(model b) | TSMIM-2

(model c) | DFM

(model d) | | DF | | | 1.64*** | 1.63*** | | | | | (0.06) | (0.10) | | PCI | 0.40*** | 0.41*** | | | | | (0.02) | (0.02) | | | | SCI | 2.43*** | | 2.57*** | | | | (0.25) | | (0.29) | | | C | 6.17*** | 6.22*** | 6.24*** | 6.17*** | | | (0.18) | (0.31) | (0.179) | (0.30) | | Observations | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | | R-squared | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.85 | | Adjusted R-squared | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.84 | Notes: 1. Correlation of GDP with PCI is 0.9 and with SCI is 0.3.

2. Standard deviation of PCI is much higher than SCI.

3. Figures in parentheses are standard error.

4. * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.010.

5. Correlation coefficients of indicators greater than 0.1 with GDP is considered as significant while computing composite indicators PCI and SCI. |

| Table 3: GDP Nowcast Performance | | Period | Nowcast | GDP actual data | Error (Actual-Forecast)2 | | TSMIM-1 | PCI | TSMIM-2 | DFM | SPF | TSMIM-1 | PCI | TSMIM-2 | DFM | SPF | | Q4:2022-23 | 8.57 | 6.71 | 8.81 | 6.92 | 4.60 | 6.90 | 2.81 | 0.03 | 3.66 | 0.00 | 5.28 | | Q1:2023-24 | 8.21 | 5.51 | 8.08 | 5.90 | 7.50 | 9.66 | 2.11 | 17.20 | 2.49 | 14.12 | 4.67 | | Q2:2023-24 | 9.08 | 7.27 | 9.04 | 7.80 | 6.30 | 9.34 | 0.07 | 4.30 | 0.09 | 2.37 | 9.26 | | Q3:2023-24 | 7.49 | 7.10 | 7.66 | 7.56 | 6.50 | 9.51 | 4.10 | 5.83 | 3.43 | 3.82 | 9.09 | | Q4:2023-24 | 6.87 | 7.15 | 7.06 | 7.38 | 6.00 | 8.35 | 2.21 | 1.46 | 1.67 | 0.94 | 5.54 | | Q1:2024-25 | 6.89 | 6.73 | 7.05 | 6.98 | 7.00 | 6.51 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.24 | | Q2:2024-25 | 5.56 | 5.16 | 6.18 | 5.65 | 7.00 | 5.61 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 1.93 | | Q3:2024-25 | 6.53 | 5.48 | 6.82 | 5.76 | 6.40 | 6.37 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.00 | | Q4:2024-25 | 6.91 | 5.92 | 7.16 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 7.38 | 0.23 | 2.15 | 0.05 | 1.92 | 0.15 | | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | 1.14 | 1.89 | 1.16 | 1.62 | 2.00 | | RMSE excluding Q1: 2023-24 | 1.09 | 1.36 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.98 | Note: Single factor models recorded a large error in Q1:2023-24. Hence, RMSE excluding Q1: 2023-24 is also presented.

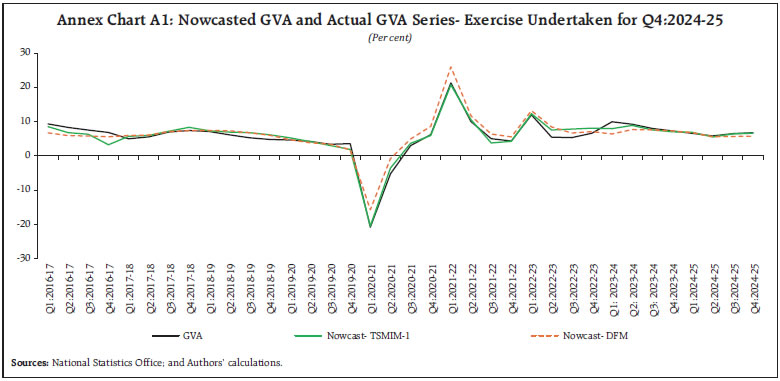

Sources: NSO; and authors’ calculations. | RMSE of SPF and model (b) were found to be the highest among all the sets of nowcasts. RMSE of DFM is the next highest primarily on account of the inability of the model to predict the growth in Q1:2023-24. TSMIM-1, followed by TSMIM-2 had the lowest RMSE in the period under study crucially underpinning the role of secondary information in improving nowcast accuracy even while excluding Q1:2023-24 from calculation of RMSE. The models using SCI have performed consistently better than the models using only single factor in most quarters in nowcasting GDP (closer to the actual estimates) from the information content available through the same set of twenty-two indicators. Chart 2 plots the nowcasts generated for each quarter vis-à-vis actual GDP and SPF forecast. Notably, during the period of high growth in 2023-24, TSMIM-1 and TSMIM-2 nowcasts were closer to the latest GDP estimates than those generated by using only DF and PCI in single-step models underpinning higher accuracy achieved due to the use of secondary factor. SPF forecasts were found to be less accurate till recently. IV.1.a Robustness Checks The same exercise was undertaken for nowcasting real gross value added (GVA) growth at basic prices for the same period. The regression estimates for Q4:2024-25 for GVA show that the coefficients of the variables of interest are significant in all models. As in the case of GDP, the model fit of TSMIM-1, and TSMIM-2 are better than that of using only DF in the case of GVA as well (Table 4).

| Table 4: GVA Regression Estimates | Dependent Variable: GVA

Method: Least Squares

Sample (adjusted): 2012Q2-2024Q4 | | Variable | TSMIM-1 (Model a) | PCI (Model b) | TSMIM-2 (Model c) | DFM (Model d) | | DF | | | 1.50*** | 1.50*** | | | | | (0.05) | (0.09) | | PCI | 0.37*** | 0.37*** | | | | | (0.01) | (0.02) | | | | SCI | 2.25*** | | 2.235*** | | | | (0.23) | | (0.26) | | | C | 6.03*** | 6.08*** | 6.11*** | 6.04*** | | | (0.16) | (0.28) | (0.16) | (0.27) | | Observations | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | | R-squared | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.86 | | Adjusted R-squared | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.86 | Notes: 1. Figures in parentheses are standard error.

2. * p<0.10, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.010

3. Correlation coefficients of indicators greater than 0.1 with GVA are considered significant while computing composite indicators PCI and SCI. | Further, like GDP, forecasted series of GVA using all models track actual GVA well for the exercise undertaken for Q4:2024-25 (Annex Chart A1). RMSE of nowcasts for real GVA growth generated using TSMIM-1 and TSMIM-2 are the lowest among all models, which improves further if Q1:2023-24 is excluded from the sample. Incidentally, RMSE of TSMIM for nowcasting GVA is lower than that of nowcasting GDP reflective of indicators capturing economic activity from supply side (Table 5). Visually, TSMIM-based nowcasts track GVA more closely than DFM based nowcasts, especially in the latest quarters, wherein the nowcasts generated for each vintage vis-à-vis actual GVA based on latest data are plotted (Chart 3). | Table 5: GVA Nowcast Performance | | Period | Nowcast | GVA actual data | Error (Actual-Forecast)2 | | TSMIM-1 | PCI | TSMIM-2 | DFM | SPF | TSMIM-1 | PCI | TSMIM-2 | DFM | SPF | | Q4:2022-23 | 7.99 | 6.51 | 7.96 | 6.73 | 6.70 | 6.60 | 1.92 | 0.01 | 1.84 | 0.02 | 5.28 | | Q1:2023-24 | 7.71 | 5.44 | 7.56 | 5.79 | 7.10 | 9.94 | 4.99 | 20.28 | 5.65 | 17.17 | 4.67 | | Q2:2023-24 | 8.84 | 7.11 | 9.02 | 7.56 | 6.20 | 9.22 | 0.15 | 4.46 | 0.04 | 2.76 | 9.26 | | Q3:2023-24 | 7.58 | 6.97 | 7.91 | 7.34 | 6.20 | 8.00 | 0.17 | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.43 | 9.09 | | Q4:2023-24 | 7.08 | 6.98 | 7.27 | 7.15 | 5.50 | 7.27 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 5.54 | | Q1:2024-25 | 6.94 | 6.57 | 7.35 | 6.76 | 6.40 | 6.55 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.24 | | Q2:2024-25 | 5.57 | 5.12 | 6.08 | 5.55 | 6.80 | 5.81 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.93 | | Q3:2024-25 | 6.41 | 5.42 | 6.61 | 5.66 | 6.40 | 6.49 | 0.01 | 1.16 | 0.01 | 0.70 | 0.00 | | Q4:2024-25 | 6.73 | 5.81 | 6.89 | 5.89 | 6.70 | 6.77 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0.15 | | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | 0.91 | 1.78 | 0.96 | 1.56 | 1.65 | | RMSE excluding Q1: 2023-24 | 0.56 | 1.01 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 1.44 | Note: Single factor models recorded a large error in Q1:2023-24. Hence, RMSE excluding Q1: 2023-24 is also presented.

Sources: National Statistics Office; and Authors’ calculations. | V. Conclusion Many important low-frequency macro-economic indicators such as GDP are subject to publication delays or lag. However, there are many high frequency coincident indicators which are correlated with the targeted macroeconomic indicator that are available at much shorter time lags. Monitoring all these coincident indicators and revising the assessment about the reference series is a difficult task for the policy makers. Combining all these coincident indicators into a composite index for nowcasting was thus developed to meet the need for reliable indication in advance of the release of the relevant macroeconomic indicator. This article uses a new framework (TSMIM), to extract maximum information relevant to nowcast the reference series. Coincident indicators are combined into a weighted composite index (PCI), which generally tracks the reference series well. However, residual information may contain some more information for the reference series which are not completely captured by PCI. Therefore, the new approach further extracts information which is not part of the already calculated composite index i.e., PCI, and has potential to be related to the reference series. These secondary indicators derived from the primary set of indicators are then again combined into a SCI with suitable weights. This article shows a relatively improved performance (both in-sample and out of sample) of the new framework (TSMIM) when compared with the baseline pure dynamic factor-based modelling (DFM) based nowcasting. TSMIM-based nowcasts track GDP and GVA more closely than pure DFM based nowcasts, when the nowcasts generated for each vintage vis-à-vis the actual official data are compared. Moreover, TSMIM framework can accommodate DFM model and can reduce forecast errors further. DFM can be used in the first stage of TSMIM and in the second stage, residual information are extracted from the coincident indicators which are not part of the dynamic factor obtained from DFM and these residuals are combined into a second factor with a suitable weights (such as correlation with the reference series). DF and second factor thus obtained produced improved nowcast of the reference series than nowcasts generated by benchmark DFM alone. Incorporating secondary information from residuals greatly improves accuracy of nowcasting and therefore, TSMIM is an important addition to the nowcasting toolkit. References Almuzara, M., Baker, K., O’Keeffe, H., & Sbordone, A. (2023). The New York Fed Staff Nowcast 2.0. New York Fed Staff Technical Paper. Bhadury, S. S., Ghosh, S., & Kumar, P. (2021). Constructing a coincident economic indicator for India: How well does it track gross domestic product? Asian Development Review. Bhattacharya, R., Pandey, R., & Veronese, G. (2011). Tracking India Growth in Real Time. National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, Working Papers 2011/90. Bok, B., Caratelli, D., Giannone, D., Sbordone, A., & Tambalotti, A. (2017). Macroeconomic Nowcasting and Forecasting with Big Data. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports. Bragoli, D., & Fosten, J. (2017). Nowcasting Indian GDP. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. Ghosh, S., & Ranjan, A. (2023). A Machine Learning Approach To GDP Nowcasting: An Emerging Market Experience. Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking. Giannone, D., Reichlin, L., & Small, D. (2008). Nowcasting: The Real Time Informational Content of Macroeconomic Data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 665-676. Higgins, P. (2014). GDPNow: A Model for GDP “Nowcasting”. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper. Hindrayanto, I., Koopman, S. J., & Winter, J. d. (2016). Forecasting and nowcasting economic growth in the euro area using factor models. International Journal of Forecasting, 1284-1305. Iyer, T., & Sen Gupta, A. (2019). Nowcasting economic growth in India: The role of rainfall. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series. Iyer, T., & Sen Gupta, A. (2019). Quarterly Forecasting Model for India’s Economic Growth: Bayesian Vector Autoregression Approach. ADB Working Paper Series. Kaustubh, K., & Ranjan, A. (2025). A multi-factor GDP nowcast model for India. Economic Modelling. Kumar, P. (2020). An Economic Activity Index for India. RBI Bulletin. Matheson, T. (2011). New Indicators for Tracking Growth in Real Time. International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. WP/11/43. Prakash, A., Bhowmick, C., & Thakur, I. (2022). Nowcasting of India’s GDP using dynamic factor model: Optimising the results. The Journal of Income & Wealth. Proietti, T., Giovannelli, A., Ricchi, O., & Citton, A. (2021). Nowcasting GDP and its components in a data-rich environment: The merits of the indirect approach. International Journal of Forecasting, 1376–1398. Roy, I., & Narayanan, K. (2018). Pull Factors of FDI: A Cross-Country Analysis of Advanced and Developing Countries. In N. Siddharthan, & K. Narayanan, Globalisation of Technology. India Studies in Business and Economics. Singapore: Springer. Roy, I., Sanyal, A., & Ghosh, A. K. (2016). Nowcasting Indian GVA Growth in a Mixed Frequency Setup. Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, 97-107. Stock, J., & Watson, M. (1989). New Indexes of Coincident and Leading Economic Indicators. Macroeconomics Annual, National Bureau of Economic Research, 351-409.

Annex A: Dynamic Factor Model A dynamic factor model assumes that many observed variables (yi,t, ..., yn,t) are driven by a few unobserved dynamic factors (f1,t, . . ., fr,t), and specific features of distinct series such as measurement errors, are captured by idiosyncratic errors (e1,t, ..., en,t). The general specification of a dynamic factor model is: where yis are the high-frequency indicators, fjs are the latent common factors, and λijs are factor loadings of factor fj on indicator yi. The error term, eit, captures the idiosyncratic component of each indicator i. Common factors and idiosyncratic components are modelled as autoregressive processes: Equations 6-8 constitute a state-space model with equation 6 being the observation equation and equations 7-8 representing transition equations. State variables and parameters of the state-space model are estimated using Kalman filter algorithm (Bok et al., 2017). The model is considered particularly suitable for monitoring macroeconomic conditions in real time as it provides flexibility to incorporate data with mixed frequency, missing values and nonsynchronous releases. In the second step, the dynamic common factor ft is used to nowcast current quarter GDP growth using a bivariate regression accounting for serial correlation in errors.3 The model specification is given below.

| Annex A Table A1: Correlation of Indicators with Real GDP Growth during June 2011- March 2025 | | Sl. No | Indicators | Correlation Coefficient | | 1 | IIP | 0.946*** | | | | (0.000) | | 2 | Domestic air cargo traffic | 0.868*** | | | | (0.000) | | 3 | Fuel Consumption | 0.851*** | | | | (0.000) | | 4 | US Payroll | 0.815*** | | | | (0.000) | | 5 | PMI Services | 0.792*** | | | | (0.000) | | 6 | Steel Consumption | 0.785*** | | | | (0.000) | | 7 | Port cargo traffic | 0.770*** | | | | (0.000) | | 8 | IIP Cement | 0.763*** | | | | (0.000) | | 9 | Automobile sales | 0.752*** | | | | (0.000) | | 10 | Power Supply | 0.741*** | | | | (0.000) | | 11 | PMI Manufacturing | 0.738*** | | | | (0.000) | | 12 | US IIP | 0.738*** | | | | (0.000) | | 13 | Naukri Jobspeak Index | 0.699*** | | | | (0.000) | | 14 | Domestic air passenger traffic | 0.692*** | | | | (0.000) | | 15 | Gross Taxes | 0.687*** | | | | (0.000) | | 16 | Railway freight | 0.668*** | | | | (0.000) | | 17 | Non-oil Non Gold Imports | 0.546*** | | | | (0.000) | | 18 | Non-oil Exports | 0.515*** | | | | (0.000) | | 19 | Foreign Tourist Arrivals | 0.449*** | | | | (0.001) | | 20 | OECD CLI | 0.405*** | | | | (0.002) | | 21 | Crude Prices | 0.398*** | | | | (0.002) | | 22 | Baltic Dry Index | 0.255* | | | | (0.057) | | 23 | US Purchasing Managers Index | 0.216 | | | | (0.110) | | 24 | Non Food Credit | 0.189 | | | | (0.163) | | 25 | Farm Tractor Sales | 0.126 | | | | (0.356) | | 26 | CPI Excluding Food and Beverage | 0.0764 | | | | (0.576) | | 27 | Money Supply M3 | -0.0874 | | | | (0.522) | Notes: 1. p-values in parentheses.

2. * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01 |

| Annex A Table A2: Coefficients of PCI and DF Regressed on Indicators | | Indicators | PCI | DF | | Coefficient | R2 | Adj_R 2 | Coefficient | R2 | Adj_R 2 | | Domestic air cargo traffic | 0.079*** | 0.853 | 0.851 | 0.316*** | 0.87 | 0.867 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Domestic air passenger traffic | 0.070*** | 0.677 | 0.671 | 0.274*** | 0.654 | 0.648 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Automobile sales | 0.067*** | 0.613 | 0.605 | 0.271*** | 0.639 | 0.632 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Baltic Dry Index | 0.037*** | 0.188 | 0.173 | 0.144** | 0.181 | 0.166 | | | (0.001) | | | (0.001) | | | | Crude Prices | 0.053*** | 0.382 | 0.371 | 0.190*** | 0.315 | 0.303 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Fuel Consumption | 0.068*** | 0.638 | 0.632 | 0.266*** | 0.615 | 0.608 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Gross Taxes | 0.067*** | 0.612 | 0.605 | 0.267*** | 0.621 | 0.614 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | IIP | 0.079*** | 0.866 | 0.864 | 0.319*** | 0.883 | 0.881 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | IIP Cement | 0.067*** | 0.617 | 0.61 | 0.258*** | 0.581 | 0.573 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Naukri Jobspeak Index | 0.069*** | 0.656 | 0.65 | 0.267*** | 0.622 | 0.615 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Non-oil Exports | 0.059*** | 0.484 | 0.474 | 0.227*** | 0.447 | 0.437 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Non-oil Non-Gold Imports | 0.064*** | 0.575 | 0.567 | 0.241*** | 0.505 | 0.496 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | OECD CLI | 0.042*** | 0.246 | 0.232 | 0.179*** | 0.279 | 0.265 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | US Payroll | 0.063*** | 0.543 | 0.534 | 0.240*** | 0.503 | 0.494 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | PMI Manufacturing | 0.068*** | 0.646 | 0.64 | 0.285*** | 0.704 | 0.699 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | PMI Services | 0.076*** | 0.794 | 0.791 | 0.310*** | 0.834 | 0.83 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Port cargo traffic | 0.067*** | 0.612 | 0.605 | 0.271*** | 0.64 | 0.634 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Power Supply | 0.065*** | 0.587 | 0.579 | 0.254*** | 0.56 | 0.552 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Railway freight | 0.073*** | 0.729 | 0.724 | 0.287*** | 0.716 | 0.711 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Steel Consumption | 0.071*** | 0.703 | 0.698 | 0.297*** | 0.766 | 0.762 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | Foreign Tourist Arrivals | 0.054*** | 0.405 | 0.394 | 0.204*** | 0.361 | 0.349 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | | US IIP | 0.068*** | 0.645 | 0.639 | 0.258*** | 0.578 | 0.57 | | | (0.000) | | | (0.000) | | | Notes: 1. p-values in parentheses.

2. * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01 |

| Annex A Table A3: Correlation of GDP with PCI Residual and DF Residual | | Variable | PCI | DF | | Domestic air cargo traffic | 0.0663 | 0.0663 | | | (0.627) | (0.627) | | Domestic air passenger traffic | -0.101 | -0.0867 | | | (0.459) | (0.525) | | Automobile sales | 0.0623 | 0.0291 | | | (0.648) | (0.831) | | Baltic Dry Index | -0.156 | -0.151 | | | (0.252) | (0.268) | | Crude Prices | -0.211 | -0.143 | | | (0.118) | (0.292) | | Fuel Consumption | 0.204 | 0.209 | | | (0.132) | (0.122) | | Gross Taxes | -0.0456 | -0.0641 | | | (0.739) | (0.639) | | IIP | 0.268** | 0.241* | | | (0.046) | (0.074) | | IIP Cement | 0.0763 | 0.0966 | | | (0.576) | (0.479) | | Naukri Jobspeak Index | -0.0675 | -0.0422 | | | (0.621) | (0.758) | | Non-oil Exports | -0.166 | -0.134 | | | (0.222) | (0.326) | | Non-oil Non-Gold Imports | -0.223* | -0.153 | | | (0.098) | (0.260) | | OECD CLI | -0.0540 | -0.0945 | | | (0.693) | (0.488) | | US Payroll | 0.212 | 0.231* | | | (0.118) | (0.087) | | PMI Manufacturing | 0.00938 | -0.0608 | | | (0.945) | (0.656) | | PMI Services | -0.0455 | -0.116 | | | (0.739) | (0.393) | | Port cargo traffic | 0.0906 | 0.0569 | | | (0.506) | (0.677) | | Power Supply | 0.0655 | 0.0794 | | | (0.631) | (0.561) | | Railway freight | -0.212 | -0.206 | | | (0.116) | (0.128) | | Steel Consumption | 0.0373 | -0.0406 | | | (0.785) | (0.766) | | Foreign Tourist Arrivals | -0.170 | -0.129 | | | (0.211) | (0.344) | | US IIP | 0.00924 | 0.0599 | | | (0.946) | (0.661) | Notes: 1. p-values in parentheses.

2. * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01 |

|