Anand Prakash*

Indian foreign exchange market has gone through a process of gradual liberalization during the

past two decades. With the adoption of market-determined exchange rate in 1993, the rupee has

faced episodes of heightened volatility, the latest being post May 22, 2013 volatility on fears of

tapering of quantitative easing by the US Fed. Excessive exchange rates volatility imposes real

costs on the economy through its effects on international trade and investment and could also

complicate the conduct of monetary policy. In view of this, there is a greater interest among

the policymakers and academia in exploring the policy space available to EMEs to deal with

any sharp volatility in the financial markets. Particularly, central bank responses to episodes of

volatility in the foreign exchange markets have come into sharper focus. Against this backdrop,

the paper analyses six major phases of volatility in Indian forex market during the period from

1993 to 2013, caused either by exogenous or endogenous factors, or a combination of both and

RBI’s response to contain the volatility. The analysis reveals that there has been a significant

increase in exchange rate volatility in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, signifying the

greater influence of volatile capital flows on exchange rate movements. An important aspect of

the policy response in India to the various episodes of volatility has been market intervention

combined with monetary and administrative measures to meet the threats to financial stability,

while complementary or parallel recourse has been taken to communications through speeches

and press releases. Availability of sufficient tools in the toolkit of a central bank is also a

necessary condition to manage crisis. The paper concludes that the structural problems present

in India’s external sector, especially the persistence of large trade and current account deficits,

will need to be addressed for a sustainable solution to the problem.

JEL Classification : F31, G15, C10

Keywords : Exchange Rate, Financial Market, Volatility

Introduction

Foreign exchange (forex) markets play a critical role in facilitating

cross-border trade, investment, and financial transactions. These markets allow firms making transactions in foreign currencies to

convert the currencies or deposits they have into the currencies or

deposits of their choice. The importance of foreign exchange markets

has grown with increased global economic activity, trade, and

investment, and with technology that makes real-time exchange of

information and trading possible. In a market determined exchange rate

system, excessive exchange rates volatility, which is out of line with

economic fundamentals, can impose real costs on the economy through

its effects on international trade and investment. Moreover, at times,

pressures from foreign exchange markets could complicate the conduct

of monetary policy.

Indian foreign exchange market has gone through a process of

gradual liberalization during the past two decades. It has indeed come a

long way since its inception in 1978 when banks in India were allowed

to undertake intra-day trade in foreign exchange (Reddy, 1999).

However, it was in the 1990s that the Indian foreign exchange market

witnessed far reaching changes along with the shifts in the currency

regime in India from pegged to floating. The balance of payments

crisis of 1991, which marked the beginning of the process of economic

reforms in India, led to introduction of Liberalized Exchange Rate

Management System (LERMS) in 1992, which was introduced as a

transitional measure and entailed a dual exchange rate system. LERMS

was abolished in March 1993 and floating exchange rate regime was

adopted. With the introduction of market-based exchange rate regime

in 1993, adoption of current account convertibility in 1994, and gradual

liberalization of capital account over the years, essential underpinnings

were provided for the foreign exchange market to flourish in India.

Today, it constitutes a significant segment of the Indian financial markets

with reasonable degree of integration with money market, government

securities market and capital market, and plays an important role in the

Indian economy. The conduct of exchange rate policy of Reserve Bank

of India (RBI) has mainly been guided by the objective of maintaining

orderly conditions in the foreign exchange market, to prevent the

emergence of destabilising and self-fulfilling speculative activities, and

allowing the exchange rate to reflect the macroeconomic fundamentals.

The alternating phases of exchange market pressure have been dealt with appropriate policy measures by the RBI partly to ‘lean against

the wind’ against speculative attacks and also to ‘lean with the wind’

in order to ensure soft landings of the exchange rate in the face of the

perceived need for correcting overvaluation (Patra & Pattanaik, 1998).

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the Euro zone

debt crisis, emerging market economies (EMEs) have faced enhanced

uncertainty. Capital flows to EMEs have become extremely volatile

with excessive capital inflows to EMEs in search of better yields

followed by sudden stops and reversals. Many major EM currencies,

including the Indian rupee, witnessed significant depreciation in the

recent period owing to the ‘announcement effect’ of the likely tapering

of quantitative easing (QE) by the US Federal Reserve (Fed). The

tightening in the overall financial market conditions started from May

22, 2013 following the testimony by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke about

the possible reduction in the bond purchases undertaken as quantitative

easing (QE). Typically, those EMEs with large current account deficits

(CAD) and relatively weaker macroeconomic conditions were worst

affected (like India, South Africa, Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia), though

currencies of countries with current account surplus (e.g., Malaysia,

Russia) were also been affected. As cited in the October 2013 Global

Financial Stability Report (GFSR), it was found that the currencies

that depreciated most were those that the 2013 Pilot External Sector

Report had assessed as overvalued. At the same time, the high foreign

exchange volatility raised the concern about the risk of overshooting

which could weigh negatively on investment and growth in the affected

economies. With the postponement of the tapering announced by the

US Fed on September 18, 2013, the markets recovered to a large extent.

The commencement of tapering by the US Fed starting from January

2014 and the subsequent announcements about the increase in its pace

has not affected the stability of the rupee, which indicates that the

markets have generally shrugged off QE tapering fears. The rupee has

remained relatively stable as compared to other major EME currencies

in the recent period.

In view of the heightened volatility in the forex market discussed

above, there is a greater interest among the policymakers and academia in exploring the policy space available to EMEs to deal with any sharp

volatility in the financial markets. Particularly, central bank responses

to episodes of volatility in the foreign exchange markets have come

into sharper focus. Against this backdrop, the paper attempts to identify

the major episodes of volatility in Indian forex market in the past

two decades, caused either by exogenous or endogenous factors, or a

combination of both. It tries to bridge the gap in the existing literature

in documenting the central bank measures in forex market, which

have hitherto focused more on empirical assessment of central bank

interventions for controlling volatility. However, besides intervention,

the central bank takes a number of monetary, administrative, moral

suasion and other kinds of measures, which are equally, if not more,

important in managing volatility. In view of the above, this paper

attempts to capture the broad gamut of measures the Reserve Bank

has taken to effectively manage various episodes of volatility in the

past two decades. It is a descriptive documentation of each episode

of forex market volatility with elaborate description of the backdrop,

detailed account of the central bank measures and enumeration of the

major outcomes. The information has been collected from various RBI

publications as well as internal notes. This format of presentation is

able to bring out clearly the various factors behind central bank actions

including the macro-financial conditions, such as, CAD, fiscal deficit,

level of forex reserves, inflation rate, etc., various measures taken by

the Reserve Bank and how effective were the measures in controlling

various episodes of volatility.

The period from 1993 to 2013 has been divided into six phases.

Accordingly, the paper has been organized in the following eight

sections. Section I provides measurement of daily annualized volatility

during various episodes of exchange market pressure. Section II sets

out the details of the first phase covering the period 1993-95 when the

rupee witnessed appreciating pressure on the back of surge in capital

inflows in post-exchange rate unification period. Section III documents

the second phase covering the period 1995-96 when the rupee witnessed

the first major episode of volatility in the Indian forex market resulting

from the contagion effect of Mexican Crisis. Section IV focuses on the

third phase covering the episodes of volatility during 1997-98 under the impact of East Asian crisis. Section V captures fourth phase covering

specific instances of volatility in the pre-crisis phase during the period

1998-2008, while Section VI captures the fifth phase covering volatility

during the global financial crisis of 2007-08 and also details lessons learnt

from the various past episodes of crises. The sixth phase covering the

recent episode of volatility following Chairman Bernanke’s testimony

of May 22, 2013 and the way forward are presented in Section VII.

Finally, Section VIII incorporates some concluding observations.

Section I

Measurement of Volatility: 1993-2013

Volatility in exchange rate refers to the amount of uncertainty or

risk involved with the size of changes in a currency’s exchange rate.

Volatility in the rupee-dollar exchange rate during various episodes of

heightened volatility in the forex market in the past two decades have

been computed using standard deviations of daily forex market returns,

which have been annualised. The rupee-dollar exchange rate data for

volatility computation have been sourced from Bloomberg. An analysis

of volatility in various phases of exchange rate pressures shows that

volatility in rupee-dollar exchange rate has exhibited mixed trends in

the past two decades of market determined exchange rate (Chart 1,

Table I). After the first major episode of volatility in 1995-96 in the wake of Mexican crisis when volatility touched the level of around 13-

14 per cent, volatility remained relatively subdued, even during the East

Asian crisis of 1997-98. However, there has been a significant increase

in exchange rate volatility in the aftermath of the global financial crisis,

signifying the greater influence of volatile capital flows on exchange rate

movements. EMEs like India, which have large current account deficit,

are particularly vulnerable to the vagaries of international capital flows

where a surge in capital flows in search of better yield is invariably

followed by reversals/sudden stops on sudden change in risk appetite

of international investors, thereby imparting significant volatility to the

EME financial markets. Volatility has increased significantly in the post

May 22, 2013 phase after Chairman Bernanke’s testimony about the

possibility of QE tapering. Among various episodes of volatility, the

annualized daily volatility was maximum at around 17.14 per cent during

the period from May 23 to September 4, 2013. However, it declined to

9.15 per cent during the period September 4, 2013 to April 2, 2014. In

terms of month-wise exchange rate volatility during the post May 22,

2013 phase, despite a sharp increase in volatility in June 2013 vis-à-vis

May 2013, measures announced in July 2013 had a dampening impact on volatility. However, despite RBI’s measures, August 2013 witnessed

intense exchange market pressure with the volatility in rupee-dollar

exchange rate touching an all time high. But the measures announced in

September and October 2013 after Governor Rajan assumed office on

September 4, 2013 have clearly led to a significant decline in volatility

from a high of 25.7 per cent in August 2013 to 18.7 per cent in September

2013 and further to 8.3 per cent in October 2013. This bears testimony

to the efficacy of RBI’s measures in controlling the recent episode of

volatility though other positive developments, both external as well as

internal, have also buoyed the market sentiment and contributed to the

strength of the rupee.

Table I: Annualised Daily Volatility in Rs-$ Exchange Rate during various Episodes of Volatility (1993-2014) |

(Per cent) |

Period |

Volatility |

September-October 1995 |

12.58 |

end-January to February 1996 |

13.94 |

August 1997 to January 1998 |

7.91 |

May to August 1998 |

7.63 |

September to November 2008 |

13.37 |

May 23 to September 4, 2013 |

17.14 |

September 4, 2013 to April 2, 2014 (after Governor Rajan took over) |

9.15 |

Monthly Volatility during the Recent Episode |

|

|

May 2013 |

|

4.47 |

|

June 2013 |

|

14.75 |

|

July 2013 |

|

10.38 |

|

Aug 2013 |

|

25.68 |

|

Sept 2013 |

|

18.71 |

|

Oct 2013 |

|

8.26 |

Section II

Post-Exchange Rate Unification Period (March 1993 to

July

1995): Surge in Capital Flows

A. Backdrop: The first phase of the post-exchange rate unification

period, spanning from March 1993 to July 1995, was marked

by a surge in capital inflows on account of liberalization in the

capital account and a move to a market determined exchange rate.

As against FDI and Portfolio flows of US$ 341 million and US$

92 million respectively, in 1992-93, the corresponding figures in

1993-94 were US$ 620 million and US$ 3490 million. Though the

CAD increased from 0.4 per cent of GDP in 1993-94 to 1.6 per

cent of GDP in 1995-96, the surplus on the capital account (3.8 per

cent of GDP in 1993-94) on account of the large capital inflows

more than compensated for the CAD, leading to large accretion

to forex reserves. The WPI inflation which stood at 8.4 per cent

in 1993-94 accelerated to 12.6 per cent in 1994-95 contributing

significantly to the overvaluation of the rupee as the rupee was

essentially range-bound during the period. The GFD which stood

at around 7 per cent of GDP in 1993-94 declined to around 5 per

cent of GDP in 1995-96. The GDP growth accelerated from 5.7 per

cent in 1993-94 to 7.3 per cent in 1995-96.

B. Actions Taken: To maintain the external competitiveness of

exports and stability of the rupee, which is a prerequisite for capital

inflows, RBI, under Governor Rangarajan, intervened in the spot market and purchased dollars and, thereafter, conducted Open

Market Operations to partly sterilize the expansionary impact on

domestic liquidity. The focus of exchange rate policy in 1993-94

was on preserving the external competitiveness of the rupee at a

time when the economy was undergoing a structural transformation

coupled with building up of the forex reserves.

C. Outcome: As a result of RBI’s intervention, India’s forex reserves

increased from US$ 6.4 billion at the end of March 1993 to US$

20.8 billion as at the end of March 1995, representing over 7 months

of import cover. There was a prolonged period of stability in the

rupee-dollar exchange rate from March 1993 to July 1995 (the

USD/Rupee rate remained range bound within Rs.31.37 and Rs

31.65 per US dollar), which was followed by a period of volatility

or reversal of the gains made by the rupee (Chart 2).

Section III

Impact of Mexican Crisis (August 1995 to March 1996)

The period from August 1995 to March 1996 has been divided

into two phases. In the first phase spanning from August to December

1995, as a result of RBI’s actions, stability was restored by October

1995 with rupee moving in range bound manner during the period

October-December 1995. However, renewed bout of volatility surfaced in January 1996 on the back of weak market sentiments and demandsupply

mismatch, which has been covered separately.

I. August-December 1995: Contagion of Mexican Crisis

A. Backdrop: The second phase spanning from August 1995 to

March 1996 was marked by intense volatility in the forex market,

which was mainly on account of the spread of the contagion

of the Mexican currency crisis in 1994, which entailed sharp

devaluation of the Mexican peso in December 1994 on account

of inappropriate policies, large CAD and weak macro-economic

fundamentals, leading to sharp slowdown in capital inflows, and

certain endogenous factors, which had accentuated the demand for

dollar. The exchange rate of rupee, which stood at 31.40 per US

dollar at end-July 1995 depreciated to 33.96 by end-September

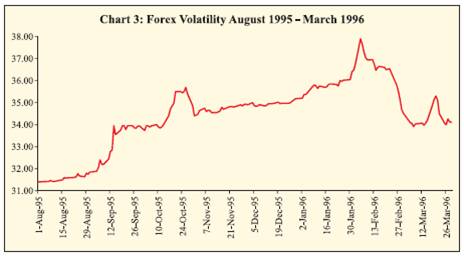

1995 and further to 36.48 by end-January 1996 (Chart 3). It may

be pointed out that the sharp depreciation of the rupee was despite

the benign macroeconomic scenario at that time with real GDP

growth accelerating from 5.7 per cent in 1993-94 to 7.3 per cent

in 1995-96. CAD as percentage of GDP, though quite sustainable,

increased from 1.0 per cent of GDP in 1994-95 to 1.6 per cent

in 1995-96 mainly because of increase in imports. GFD as a

percentage of GDP also moderated from around 6.96 per cent in

1993-94 to 5.05 per cent in 1995-96. However, the annual average

WPI inflation rate (base 1993-94=100) was quite high at 12.6 per cent during 1994-95, which contributed significantly towards the

overvaluation of the rupee in real terms, though in nominal terms

the rupee had remained mostly range bound for a substantial period

of time before the volatility episode.

B. Actions Taken: As the rupee was overvalued in REER terms, the

RBI allowed the rupee to depreciate but intervened in the market

to ensure that the market corrections were calibrated and orderly.

The RBI intervened in the second fortnight of October 1995 to

the tune of US$ 912.5 million. Further, certain administrative

measures were initiated to reduce the leads and lags in import

payments and export realization and to improve inflows. Some

of the major administrative/monetary measures taken by the RBI

under Governor Rangarajan in October/November 1995, inter

alia, included:

-

Imposition of interest surcharge on import finance with effect

from October 1995,

-

Tightening of concessionality in export credit for longer

periods,

-

Easing of CRR requirements on domestic as well as nonresident

deposits from 15.0 per cent to 14.5 per cent in

November 1995,

-

Foreign currency denominated deposits like FCNR(B) and

NR(NR)RD were exempted from CRR requirements, and

-

Interest rates on NRE deposits were increased.

C. Outcome: The decisive and timely policy actions brought stability

to the market and the rupee resumed trading within the range of

Rs.34.28 – Rs. 35.79 per US dollar in the spot segment during the

period, October 1995 to December 1995.

II. January-March 1996: Renewed Volatility on Weak Sentiments

A. Backdrop: Yet another bout of sharp depreciation of the rupee

was witnessed towards the end of January 1996 and in the first

week of February 1996, when the rupee touched a low of Rs.37.95

in the spot market while the three-month forward premia rose to

around 20 per cent. As already mentioned in the previous section,

the sharp depreciation in the exchange rate of the rupee took place despite benign macro-economic fundamentals like GDP growth

accelerating to 6.4 per cent in 1994-95 from 5.7 per cent in the

previous year, low CAD of 1.0 per cent in 1994-95 and reduction in

GFD to 5.7 per cent of the GDP in 1994-95 from around 7 per cent

in the previous year. However, the WPI inflation was quite high

at 12.6 per cent. The depreciation was triggered by weak market

sentiment coupled with demand-supply mismatch resulting from

buoyant imports on the back of acceleration in economic activities

and slowdown in capital flows to EMEs on a reassessment of the

credit risks involved in the wake of the Mexican crisis.

B. Actions taken: In order to curb the volatility in the spot as well

as forward market, spot sales followed by buy-sell swaps were

undertaken on several occasions. In addition, direct forward sales

were also resorted to. As at the end of March 1996, the RBI’s

cumulative forward sales obligations were to the tune of US$ 2.3

billion, spread over the next six months. As a result of the RBI’s

intervention operations to contain volatility in the forex market,

RBI’s foreign currency assets, which stood at 19.0 billion at end-

August 1995, declined to US$ 15.9 billion by end-February 1996.

Apart from the intervention efforts, a number of administrative

measures were also initiated on February 7, 1996 to encourage

faster realization of export proceeds and to prevent an acceleration

of import payments, i.e., to reduce the lags and leads.

The measures, inter alia, included:

-

Increase in interest rate surcharge on import finance from 15

to 25 per cent,

-

discontinuation of Post-Shipment Export Credit denominated

in US dollars (PSCFC) with effect from February 8, 1996,

-

Weekly reporting to the RBI of cancellation of forward

contracts booked by ADs for amounts of US$ 1,00,000 and

above.

-

Other measures included relaxation in the inward remittance

of GDR proceeds, relaxation in the external commercial

borrowing (ECB) norms, freeing of interest rate on postshipment

export rupee credit for over 90 days and upto 180

days, etc.

C. Outcome: These measures enabled the rupee to stage a strong

recovery in March-April 1996 and thereafter upto June 1996,

the rupee generally remained range-bound within Rs.34 – Rs.35.

The forward premia also declined and by the end of June 1996,

the premia were well within the 10-11 per cent range, reflecting

the interest rate differentials. Thus, the active intervention by

the Reserve Bank in spot, forward and swap markets during the

period did have an impact on the exchange market and domestic

liquidity situation and helped in smoothening the volatility rather

than propping up the exchange rate. The period from May 1996 to

mid-August 1997 was a period of stability with the rupee trading in

a narrow range of 35 - 36 per US dollar. As a result of substantial

capital inflows, forex assets of the RBI increased from US$ 17.0

billion at the end of March 1996 to US$ 22.4 billion at the end

of March 1997 and to around US$ 26.4 billion as at the end of

August, 1997.

Section IV

Impact of East Asian Crisis (August 1997 to August 1998)

The period from August 1997 to August 1998 has been divided into

two phases. In the first phase spanning from August 1997 to April 1998,

as a result of RBI’s actions, stability was restored by March 1998 with

rupee experiencing moving in a range-bound manner during March-

April 1998. However, renewed bout of volatility surfaced in May 1998

on the back of enhanced uncertainties emanating from spread of the

crisis, which has been covered separately.

I. August 1997 to April 1998: Volatility in the Wake of Outbreak of

Asian Crisis

A. Backdrop: The third phase spanning from mid-August 1997

to August 1998, posed severe challenges to exchange rate

management due to the contagion effect of the South-East Asian

crisis, economic sanction imposed by many industrialized nations

after the nuclear explosion in Pokhran (India) in May 1998 and

the downgrading of the sovereign rating of India by certain

international rating agencies. The monthly average Rs-$ exchange rate, which was quite stable prior to the onset of the crisis and stood

at 35.92 per US dollar in August 1997, depreciated continuously

during the crisis period and reached a low of 42.76 per US dollar

in August 1998, i.e., a depreciation of 16 per cent during the period

(Chart 4). This sharp depreciation took place against the backdrop

of worsening macroeconomic fundamentals, which was reflected

in significant deceleration in GDP growth to 4.3 per cent in 1997-

98 from 8.0 per cent in 1996-97. GFD increased sharply from

4.8 per cent of GDP in 1996-97 to 5.8 per cent in 1997-98. The

CAD, which stood at around 1.2 per cent of GDP during 1996-97,

increased marginally to 1.4 per cent of GDP in 1997-98. However,

WPI inflation was low at 4.4 per cent during 1997-98 (4.6 per cent

in 1996-97). It may be pointed out that the relative stability in

exchange rate for a prolonged period of time prior to the crisis led

to some complacency on the part of market participants who kept

their oversold or short position unhedged and substituted some

domestic debt with foreign currency borrowings to take advantage

of interest rate differential. However, in the wake of developments

in South East Asia and changed perception of a depreciating rupee,

there was a rush to cover un-hedged positions by the market

participants in the latter part of August 1997, which resulted in the

rupee coming under pressure and the forward premia firming up in

the first week of September 1997.

B. Actions Taken: In order to restore stability, the RBI intervened in

the spot, forward and swap markets. In September 1997 alone, RBI

was net seller in the forex market to the tune of US$ 978 million,

while during the period November 1997 to July 1998, RBI was net

seller to the tune of US$ 3.1 billion. As a result of RBI’s intervention

in the forward market to manage expectations and bring forward

premia down, RBI’s forward laibilities increased from US$ 40

million in August 1997 to a peak of US$ 3.2 billion in January 1998

but came down subsequently as normalcy returned to the market.

Apart from intervention operations, the RBI also initiated stringent

monetary and administrative measures to stem the unidirectional

expectation of a depreciating rupee and curb speculative attacks

on the currency. Some of the important measures taken by the

RBI under Governor Rangarajan (upto November 22, 1997) and

subsequently under Governor Jalan during the period from August

1997 to April 1998 are set out below:

-

With a view to reducing arbitrage opportunities between forex

market and the domestic rupee markets, and thereby reducing

the demand for dollars, the interest rate on fixed rate ‘repos’

was raised to 5 per cent from 4.5 per cent,

-

The CRR requirement of scheduled commercial banks was

raised by 0.5 percentage point.

-

Incremental CRR of 10 per cent on NRERA and NR(NR)

deposits were removed with effect from the fortnight beginning

December 6, 1997.

-

The interest rate on post-shipment export credit in rupees for

periods beyond 90 days and up to six months was raised from

13 per cent to 15 per cent,

-

In respect of overdue export bills, a minimum interest rate of

20 per cent per annum was prescribed,

-

An interest rate surcharge of 15 per cent on lending rate

(excluding interest tax) on bank credit for imports was

introduced.

On Jan 6/16, 1998, more measures were taken, which included

-

Raising of cash reserve ratio requirement for banks from 10

per cent to 10.5 per cent,

-

Raising Bank Rate from 9 per cent to 11 per cent,

-

Raising interest rate on fixed rate repos from 7 per cent to 9

per cent,

-

Reducing access of banks to export and general refinance

facility from RBI and

-

Prohibiting banks from taking any overnight currency position

from January 6, 1998.

C. Outcome: As a result of these measures, stability returned in the

foreign exchange market and more importantly, the expectations of

the market participants about further depreciation in the exchange

rate of rupee were contained and also reversed to a certain extent.

The exchange rate of rupee, which had depreciated to Rs. 40.36

per US dollar as on January 16, 1998, appreciated to Rs. 39.50 per

dollar on March 31, 1998. The exchange rate moved in a narrow

range around Rs.39.50 per US dollar in March-April 1998. The

six month forward premia, which reached a peak of around 20 per

cent in January 1998, came down to 7.0 by the end of March 1998.

Forward liabilities of the Reserve Bank declined from a peak of

US $ 3.2 billion at the end of January 1998 to US $ 1.4 billion by

April 1998.

II. May-August 1998: Renewed Volatility due to Spread of Asian

Crisis

A. Backdrop: In May 1998 there were again uncertainties in

market expectations due to the spread of the South –East Asian

crisis to Brazil and Russia, nuclear weapon testing in Pokhran

(India), which resulted in economic sanctions being imposed by

the US and certain other industrialized countries, suspension of

fresh multilateral lending (except for certain specified sectors),

downgrading of country rating by international rating agencies and

reduction in investment by Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs).

As a result of these developments, the forex market experienced

increased pressure during the period May-August 1998. The

exchange rate of the rupee, which was Rs 39.74 at the end of April

1998, depreciated to Rs 41.50 by the end of May 1998 and further to around Rs 42.47 by the end of June 1998, and continued to

remain at these levels till mid August 1998 when it crossed Rs 43

mark for a brief period prompting RBI to take certain measures.

B. Actions taken: Some important measures announced by the RBI

during the period have been set out below:

-

Export credit denominated in foreign currency was made

cheaper and banks were advised to charge a spread of not

more than 1.5 per cent above LIBOR as against the earlier

norm of not exceeding 2-2.5 per cent over LIBOR.

-

Exporters were also allowed to use their balances in EEFC

accounts for all business related payments in India and abroad

at their discretion,

-

Withdrawal of the facility of rebooking of cancelled forward

contracts for trade related transactions including imports, etc.

-

As a measure of abundant precaution and also to send a

signal to the world regarding the intrinsic strength of the

economy, India floated the Resurgent India Bonds (RIBs) in August 1998, which was very well received by the Non

Resident Indians(NRIs)/ Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) and

subscribed to the tune of US$ 4.2 billion.

C. Outcome: As a result of the measures announced by the RBI in

August 1998, the rupee, which crossed Rs 43 mark for a brief period

in August 1998, climbed back to Rs 42.50 level by end-August

1998. The rupee remained range bound after that and hovered

around 42.50 per US dollar up to March 1999 but depreciated a

bit and crossed the Rs. 43 per US dollar mark in the subsequent

months.

D. Lessons learnt from the Asian Crisis: On hindsight, one could

say that India was successful in containing the contagion effect of

the Asian crisis due to swift policy responses to manage the crisis

and favourable macroeconomic conditions. During the period

of crisis, India had a low CAD, comfortable foreign exchange

reserves amounting to import cover of over seven months, a

market determined exchange rate, low level of short-term debt, and absence of asset price inflation or credit boom. Apart from

prudent policies pursued over the years, sound capital controls

also helped in insulating the economy from contagion effect of

the East Asian crisis. Thus, sound macro-economic fundamentals,

especially sustainable level of CAD, and prudent capital controls

helped India to escape from the contagion effect of the Asian crisis

Section V

The Pre Crisis Phase (September 1998 till August 2008)

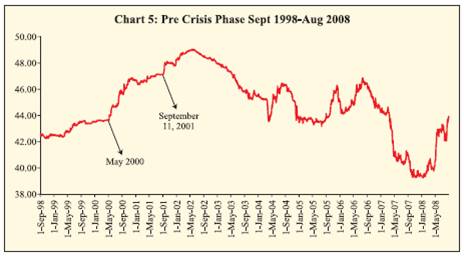

In the fourth phase, starting from September 1998 onwards (i.e., till

the advent of global financial crisis in 2008), the forex markets generally

witnessed stable conditions with brief phases of volatility caused due

to certain domestic and international events like the Indo-Pak border

tension in June 1999, terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre, New

York on September 11, 2001 and the attack on Iraq by America which

resulted in a oil price shock, etc. (Chart 5) The periods of volatility were

managed mainly by intervention in the spot and swap markets, floatation

of the India Millennium Deposit (IMD) in September/October 2000,

which helped in mobilizing US$ 5.5 billion, and appropriate monetary

/administrative measures. Due to continuous excess supply of dollars

in the period from April 2002 to May 2008 and intervention by RBI

to maintain the stability and external competitiveness of the rupee, the foreign currency assets of the RBI rose from US$ 51.0 billion as at end-

March 2002 to US$ 305 billion as at end-May 2008.

Two specific instances of volatility (i) during 2000 on higher imports

and reduced capital flows and (ii) after the terrorist attack at World

Trade Centre (WTC) on September 11, 2001 and RBI’s response have

been detailed below:

I. Episode of Volatility in 2000: Higher imports and Reduced

Capital Flows

A. Background: The stability in the foreign exchange market

exhibited during the latter part of 1999 was carried over to the

month of April 2000 with the rupee hovering within a narrow band

of 43.4 – 43.7 per US dollar. However, there was a sudden change

in market perception on the rupee from the second week of May

2000 due to higher import payments and reduced capital inflows.

The exchange rate depreciated from Rs.43.64 per US dollar

during April 2000 to Rs.44.28 on May 25, 2000 as the market was

characterised by considerable uncertainty.

B. Actions taken: Apart from intervention (net sales of US$ 1.9

billion during May-June 1998), the RBI under Governor Jalan took

a number of administrative measures to contain volatility in the

forex market, which had a salutary impact. The measures taken on

May 25, 2000 included:

(i) an interest rate surcharge of 50 per cent of the lending rate on

import finance was imposed with effect from May 26, 2000,

as a temporary measure, on all non-essential imports,

(ii) it was indicated that the Reserve Bank would meet, partially

or fully, the Government debt service payments directly as

considered necessary;

(iii) arrangements would be made to meet, partially or fully, the

foreign exchange requirements for import of crude oil by the

Indian Oil Corporation;

(iv) the Reserve Bank would continue to sell US dollars through

State Bank of India in order to augment supply in the market

or intervene directly as considered necessary to meet any

temporary demand-supply imbalances;

(v) banks would charge interest at 25 per cent per annum

(minimum) from the date the bill fell due for payment in

respect of overdue export bills in order to discourage any

delay in realisation of export proceeds;

(vi) authorised dealers acting on behalf of FIIs could approach the

Reserve Bank to procure foreign exchange at the prevailing

market rate and the Reserve Bank would, depending on market

conditions, either sell the foreign exchange directly or advise

the concerned bank to buy it in the market; and

(vii) banks were advised to enter into transactions in the forex

market only on the basis of genuine requirements and not for

the purpose of building up speculative positions.

Subsequently, the exchange rate of the rupee, which was moving

in a range of Rs. 44.67-44.73 per US dollar during the first half of July

2000 touched a low of Rs 45.07 per US dollar on July 21, 2000, the day

on which RBI announced certain monetary measures, which have been

set out below:

-

Raising of CRR by 0.5 percentage points to 8.5 per cent from

8.0 per cent;

-

Raising of bank rate by one percentage point from 7 per cent

to 8 per cent and

-

Reduction of 50 per cent in refinance facilities including

collateralised lending facility available to the banks.

C. Outcome: As a result of these measures, stability was restored

with the forex market remaining relatively quiet during September-

October 2000. During the months of November and December

2000, the exchange rate of the rupee displayed appreciating trend

in the midst of positive sentiments in the foreign exchange market

created by inflows coming from India Millenium Deposits (IMDs).

After opening the month of November 2000 at Rs. 46.85 per US

dollar, the rupee appreciated to the levels of Rs.46.53 per US dollar

before closing the month at Rs. 46.84 per US dollar, almost close

to the opening level of the month. The rupee closed the month of

December 2000 at Rs. 46.67 per US dollar. The orderly conditions

in the forex market continued in the last quarter of 2000-01 as well.

II. Episode of Volatility in 2001: September 11, 2001 Terrorist

Attacks

A. Background: The stability in the forex market witnessed during

the first five months of financial year 2001-02 (April-August) with

the rupee depreciating marginally from 46.64 at end-March 2001

to 47.15 per US dollar at end-August, 2001 could not be sustained

in September 2001. The unprecedented attacks by terrorists at

strategic locations in New York and Washington on September

11, 2001 brought international financial markets into turmoil. The

Indian financial markets also experienced repercussions of the

horrifying events. As a result, the exchange rate of Indian rupee,

which stood at 47.41 per US dollar on September 11, 2001 touched

the level of 48.43 on September 17.

B. Actions Taken: The Reserve Bank tackled the situation through

quick responses in terms of net sales in the forex market to the tune

of US$ 894 million in September 2001 and package of measures,

which have been set out below:

The measures taken by the Reserve bank under Governor Jalan

included:

-

Reiteration by the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates stable with

adequate liquidity;

-

Assurance to sell foreign exchange to meet any unusual supply demand

gap;

-

Opening a purchase window for select Government securities on

an auction basis;

-

Relaxation in FII investment limits upto the sectoral cap/statutory

ceiling;

-

A special financial package for large value exports of six select

products;

-

Reduction in interest rates on export credit by one percentage

point, etc.

C. Outcome: The above measures coupled with announcement of

the mid-term review of monetary and credit policy on October

22, 2001, which brought in easy liquidity conditions and softer interest rate regime and aided the market sentiment, helped in

restoring stability to the forex market quickly. During the last

quarter of 2001 (October-December), the forex market generally

witnessed stable conditions with the exchange rate of the rupee

hovering around Rs. 48 per US dollar amidst steady supply of

dollars and modest corporate demand. The benign macroeconomic

environment also helped in achieving stability quickly with GDP

growth accelerating from 4.3 per cent in 2000-01 to 5.5 per cent in

2001-02. The current account was in surplus at 0.7 per cent of the

GDP. WPI inflation was also quite low at 3.6 per cent in 2001-02

(7.2 per cent in 2000-01). However, GFD increased from 5.7 per

cent in 2000-01 to 6.2 per cent in 2001-02.

Section VI

The Global Financial Crisis (2008-09 To 2011-12)

I. Volatility in 2008-09: Collapse of Lehman Brothers

A. Background: Prior to the advent of global financial crisis in 2008,

external sector developments in India were marked by strong capital

flows, which resulted in the exchange rate of the Indian rupee witnessing

appreciating trend up to 2007-08. The robust macro-economic

environment with GDP expanding at over 9 per cent during 2006-07

and 2007-08, CAD standing at 1.3 per cent of GDP in 2007-08 (1.0 per

cent in 2006-07) and WPI inflation standing at a comfortable 4.7 per

cent during 2007-08 also facilitated strong capital inflows. However,

there was a sudden change in the external environment following the

Lehman Brothers’ failure in mid-September 2008. The global financial

crisis and deleveraging led to reversal and/ or modulation of capital

flows, particularly FII flows, ECBs and trade credit. Large withdrawals

of funds from the equity markets by the FIIs, reflecting the credit

squeeze and global deleveraging, resulted in large capital outflows

during September-October 2008, with concomitant pressures in the

foreign exchange market across the globe, including India.

After Lehman’s bankruptcy, the rupee depreciated sharply from around

Rs. 48 levels, breaching the level of Rs.50 per US dollar on October 27,

2008 (Chart 6). The Reserve Bank scaled up its intervention operations during the month of October 2008 (record net sales of US$ 18.7 billion

during the month). Despite significant easing of crude oil prices and

inflationary pressures in the second half of the year, declining exports

and continued capital outflows led by global deleveraging process and

the sustained strength of the US dollar against other major currencies

continued to exert downward pressure on the rupee. With the spot

exchange rates moving in a wide range, the volatility of the exchange

rates increased during this period.

B. Actions Taken: The Reserve Bank under Governor Subbarao took

a number of measures to control volatility, which included:

-

Announcement in mid-September 2008 by the Reserve Bank

about its intentions to continue selling foreign exchange (US

dollar) through agent banks to augment supply in the domestic

foreign exchange market or intervene directly to meet any

demand-supply gaps.

-

A rupee-dollar swap facility for Indian banks was introduced

with effect from November 7, 2008 to give the Indian

banks comfort in managing their short-term foreign funding

requirements. For funding the swaps, banks were also

allowed to borrow under the LAF for the corresponding tenor

at the prevailing repo rate. The forex swap facility, which

was originally available till June 30, 2009, was extended up to March 31, 2010; however, this was discontinued in

October 2009.

-

The Reserve Bank also continued with Special Market

Operations (SMO) which were instituted in June 2008 to

meet the forex requirements of public sector oil marketing

companies (OMCs), taking into account the then prevailing

extraordinary situation in the money and foreign exchange

markets; these operations were largely (Rupee) liquidity

neutral.

-

Finally, measures to ease forex liquidity also included those

aimed at encouraging capital inflows, such as, an upward

adjustment of the interest rate ceiling on foreign currency

deposits by non-resident Indians, substantially relaxing

the ECB regime for corporates, and allowing non-banking

financial companies and housing finance companies to access

foreign borrowing.

C. Outcome: As a result of the Reserve Bank’s actions in the foreign

exchange market, the pressure eased from December 2008 as

liquidity conditions in the foreign exchange market returned to

normal. With the return of some stability in international financial

markets and the relatively better growth performance of the

Indian economy, the rupee generally appreciated against the US

dollar during 2009-10 on the back of significant turnaround in FII

inflows, continued inflows under FDI and NRI deposits, better-than

expected macroeconomic performance in 2009-10 and weakening

of the US dollar in the international markets. The volatility in the

foreign exchange market declined after the introduction of the forex

swap facility. Additionally, the outcome of the general elections,

which generated expectations of political stability, buoyed market

sentiment and contributed towards the strengthening of the rupee,

especially from the second half of May 2009. As a result of these

developments, the rupee, which depreciated sharply by 21.5 per

cent from 39.99 as at end-March 2008 to 50.95 at end-March

2009 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, staged a smart

turnaround and appreciated by around 12.9 per cent in 2009-10 to

45.14 per US dollar as at end-March 2010.

II. Volatility in 2011-12: Deepening of Euro Zone Debt Crisis &

Weak Fundamentals

A. Background: After being largely range bound in the first four

months of the financial year 2011-12, rupee depreciated by about

17 per cent during August to mid-December of 2011, reflecting

global uncertainties and domestic macro-economic weakness. The

S&P’s sovereign rating downgrade of the US economy, deepening

euro area crisis and lack of credible resolution mechanisms led to

enhanced uncertainty and reduced risk appetite in global financial

markets for EME assets, which resulted in a flight to US dollar, as

it was considered a safe asset vis-à-vis the riskier EME assets by

investors, notwithstanding the economic woes of the US, as US

dollar is considered numero uno currency at the time of uncertainty

and crisis. With US dollar appreciating as a result, most currencies,

including the Indian rupee came under pressure.

B. Actions Taken: Considering the excessive pressures in the

currency markets, the Reserve Bank under Governor Subbarao

intervened in the foreign exchange market through dollar sale. It

also took several capital account measures to stabilise rupee that

included:

-

Deregulation of interest rates on rupee denominated NRI

deposits and enhancing the all-in-cost ceiling for ECBs with

average maturity of 3-5 years.

-

Ceilings for FIIs’ investment in government securities and

corporate bonds were raised by US$ 5 billion each to US$ 15

billion and US$ 45 billion, respectively.

Additionally, the Reserve Bank initiated various administrative

steps to curb speculation, which included:

-

Withdrawing the facility of cancellation and rebooking of

contracts available under contracted exposure to residents and

FIIs;

-

Reducing the limit under past performance facility for

importers to 25 percent of the limit available at that time;

-

Making the past performance facility available to exporters

and importers only on a delivery basis, mandating that all cash/ tom/ spot transactions by ADs on behalf of clients were

to be undertaken for actual remittances/ delivery only and

could not be cancelled/ cash settled;

-

Reducing the net overnight open position limit (NOOPL) of

ADs across the board;

-

Mandating that the intra-day position/ daylight limit of ADs

should not exceed the existing NOOPL approved by the

Reserve Bank.

-

The taking of position by banks, in the currency futures

segment, was also curbed, because it was rampantly used for

arbitrage between the OTC and the currency futures, which

exacerbated the volatility in the forex market.

C. Outcome: As a result of the series of measures undertaken to

improve dollar supply in the foreign exchange market as also to

curb speculation, the rupee appreciated by 11 per cent from 54.24

per US dollar on December 15, 2011 to 48.68 by February 6, 2012,

before weakening again. The renewed pressure on rupee was

mainly due to widening trade deficit, drying up of capital flows,

particularly FII flows and apprehension about the exit of Greece

from the euro.

Measures taken in May-June 2012

In order to improve the inflows as also to reduce the volatility in the

rupee, the Reserve Bank under Governor Subbarao took additional

measures in May-June, 2012.

The measures in May 2012 included increase in interest rate

ceiling on FCNR(B) deposits, deregulation of ceiling on interest

rate for export credit in foreign currency, and requirement to

convert 50 per cent of the balances in the EEFC accounts to rupee

balances.

Additional measures were taken In June 2012, in consultation

with the government, which included, inter alia, allowing ECB

for Indian companies for repayment of outstanding rupee loans

towards capital expenditure under the approval route, enhancing

the limit for FII investment in G-secs by US$ 5 billion to US$ 20

billion, rationalisation of FII investment in infrastructure debt in terms of lock in period and resident maturity, allowing Qualified

Foreign Investors (QFIs) to invest in mutual funds that held at least

25 per cent of their assets in infrastructure under the sub-limit for

investment in such mutual funds and broadening the investor base

for G-Secs to include certain long-term investor classes, such as,

Sovereign Wealth Funds, insurance funds and pension funds.

Outcome: The measures during May-June 2012 helped in

stabilizing the rupee, which moved in a range-bound fashion in the

subsequent months.

Some lessons from Various Past Episodes of volatility in the Forex

Market

An important aspect of the policy response in India to the various

episodes of volatility has been market intervention combined with

monetary and administrative measures to meet the threats to financial

stability while complementary or parallel recourse has been taken

to communications through speeches and press releases. Empirical

evidence in the Indian case has generally suggested that in the present

day managed float regime of India, intervention has served as a potent

instrument in containing the magnitude of exchange rate volatility of

the rupee and the intervention operations do not influence as much the

level of rupee (Pattanaik and Sahoo, 2001; Kohli, 2000; RBI, 2005-06).

The message that comes out from this discussion of various episodes

of volatility of exchange rate of the rupee and the policy responses

thereto is clear: flexibility and pragmatism have been the cornerstone of

exchange rate policy in developing countries, rather than adherence to

strict theoretical rules. It also underscores the need for central banks to

keep instruments/policies in hand for use in difficult situations. Thus,

availability of sufficient tools in the toolkit of a central bank is also a

necessary condition to manage crisis.

India was able to escape the contagion effect of various currency

crises in the second half of the nineties mainly because of prudent

forex and reserve management policies and also, to an extent, because

of relatively closed nature of its economy on account of sound capital

controls. Indian rupee is fully convertible so far as current account transactions are concerned, but the process of opening up of the

capital account has been gradual though a number of capital account

liberalization measures have been taken over the years. The capital

controls have worked well in the Indian case as they have helped in

insulating the economy, to an extent, from the vagaries of international

capital flows. India has consciously tried to reduce debt-creating flows,

especially those which are essentially short-term in nature.

The Asian crisis and the more recent global financial crisis have

underscored the importance of having certain necessary capital control in

place (even international financial institutions like the IMF have revised

their stance in this regard) as unfettered capital account liberalization

is no longer considered the most desirable thing. Additionally, the

various crises of the past two decades have highlighted the need for

the EMEs to maintain a healthy forex reserve cover as this helps in

inspiring confidence of the market in the ability of the central bank to

contain volatility at the time of any crisis. Since EMEs are especially

vulnerable to reversals and sudden stops in capital flows, this issue

assumes paramount significance for ensuring financial stability of the

EMEs. Even the debate surrounding the optimal level of reserves, based

on various yardsticks, such as, import cover of reserves, Guidotti-

Greenspan rule, liquidity-at-risk rule, etc., is inconclusive and, recent

developments have established that having a large quantum of reserves

has turned out to be beneficial for EMEs in dealing with various

episodes of crises, notwithstanding the costs associated with holding

large reserves, as the quasi-fiscal costs are miniscule in comparison

with the benefits in terms of financial stability and confidence.

It is noteworthy that most of the measures taken by the RBI during

the period of analysis aimed at curbing speculation and essentially

related to the external sector/entities and were not general in nature.

The measures, including the increase in fixed rate repo twice at the

time of Asian financial crisis, were basically aimed at curbing arbitrage

opportunity between money and forex market and not specifically as a

tool to induce greater capital flows for which a number of other measures,

including hike in NRI deposit rates to increase their attractiveness and

easing of ECB norms were taken.

Section VII

Episode of Volatility Post Chairman Bernanke’s

Testimony on May 22, 2013

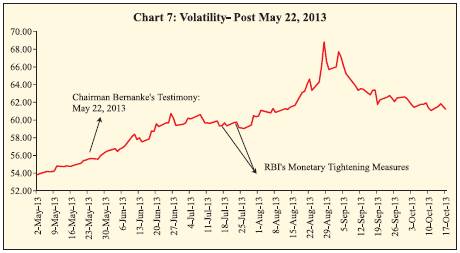

A. Backdrop to the Recent Episode of Volatility

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the Euro zone

debt crisis, EMEs have faced enhanced uncertainty. Capital flows

to EMEs have become extremely volatile with excessive capital

inflows to EMEs in search of better yields, resulting from massive

quantitative easing (QE) undertaken by the advanced economies

to pump prime their economies, followed by sudden stops and

reversals as witnessed in the post May 22, 2013 period on fears

of tapering of the QE programme. As a result of substantial

slowdown in capital inflows, the rupee experienced significant

depreciating pressure from the second half of May 2013 with the

rupee depreciating sharply by around 19.4 per cent against the US

dollar between May 22, 2013 when it stood at 55.4 per US dollar

and August 28, 2013 when it touched historic low of 68.85 per

US dollar on the back of sharp reversals in capital inflows and

unsustainable level of CAD (4.8 per cent of GDP in 2012-13)

coupled with weak macroeconomic environment in the form of

sharp deceleration in GDP growth rate (4.5 per cent in 2012-13

and 4.4 per cent in Q1 of 2013-14), high inflation (WPI inflation

of 7.4 per cent in 2012-13), large fiscal deficit (4.9 per cent of

GDP in 2012-13), etc (Chart 7). Though the rupee was generally depreciating in line with economic fundamentals even prior to

Chairman Bernanke’s testimony on May 22, 2013, his testimony,

which led to overarching concern about possibility of early tapering

of QE programme by the US Fed as signs of US recovery emerged,

triggered large selloffs by the FIIs in most EMEs, including India,

leading to heightened volatility in financial markets in the EMEs

and sharp depreciation of EME currencies, including the Indian

rupee, which was one of the worst performers during the period

from the second half of May 2013 to August 2013. The hardening

of long-term bond yields in the US and other advanced economies

increased their attractiveness prompting foreign investors to pull

funds out of riskier emerging markets, which received large capital

inflows in search of better yield, as a recovery in the US made

the EME fixed income assets less attractive vis-a-vis the US,

especially in the absence of large quantities of cheap money to

invest in the event of QE tapering. The sharp depreciation of the

rupee was not unique to India. A number of other emerging market

currencies, such as, South African rand, Brazilean real, Turkish

lira, Indonesian rupiah etc., witnessed similar trends. Many of

the EMEs, including India, resorted to forex market intervention

coupled with other policy measures, such as, hike in interest rates,

import compression of non-essential items, incentivisation of

capital inflows, removal of bottlenecks to inflows, etc., to stabilise

their currencies, which yielded mixed results.

B. Measures taken by the RBI to contain volatility

In view of the increased exchange rate volatility in the domestic

forex market, especially after Chairman Bernanke’s testimony

on May 22, 2013, the Reserve Bank under Governor Subbarao

announced a number of monetary policy measures on July 15,

2013. The measures, though intended to stem the volatility in the

forex market, primarily operated through their effect on liquidity

in the banking system by making it relatively scarce, thereby

reducing demand for foreign currency. The measures included:

-

Recalibration in MSF rate with immediate effect to 300 basis

points above the repo rate, i.e., the MSF rate was increased to

10.25 per cent from the earlier 8.25 per cent,

-

Limiting overall allocation of funds under LAF to 1.0 per cent

of NDTL of the banking system reckoned at Rs. 75,000 crore

with effect from July 17, 2013 and

-

Announcement to conduct open market sales of government

securities of Rs. 12,000 crore on July 18, 2013.

While the above set of measures had a restraining effect on

volatility with a concomitant stabilising effect on the exchange rate,

based on a review of these measures, and an assessment of the liquidity

and overall market conditions going forward, it was decided on July 23,

2013 to modify the liquidity tightening measures.

-

The modified norms set the overall limit for access to LAF

by each individual bank at 0.5 per cent of its own NDTL

outstanding as on the last Friday of the second preceding

fortnight effective from July 24, 2013.

-

Moreover, effective from the first day of the fortnight

beginning from July 27, 2013, banks were required to maintain

a minimum daily CRR balance of 99 per cent of the average

fortnightly requirement.

However, with the return of stability in the forex market, in the midquarter

review of Monetary Policy on September 19, 2013, a calibrated

unwinding of exceptional measures of July 2013 was undertaken,

Accordingly, MSF rate was reduced by 75 bps to 9.5 per cent and the

requirement of maintenance of minimum daily CRR balance by the

banks was reduced to 95 per cent along with a 25 bps increase in repo

rate to 7.5 per cent. In continuation with the calibrated unwinding,

MSF rate was reduced further by 50 bps to 9.0 per cent on October 7,

2013 along with introduction of 7 days and 14 days term repo facility

and liquidity injection to the tune of Rs. 99.74 billion through OMO

purchase auction.

Apart from the monetary measures, the Reserve Bank made net

sales to the tune of US$ 10.8 billion in the forex market during the

period May-August 2013 (around US$ 6.0 billion in July 2013 and

US$ 2.5 billion in August 2013). The Reserve bank also intervened in

the forward market with RBI’s outstanding net forward sales nearly doubling to US$ 9.1 billion as at end-August 2013 from US$ 4.7 billion

in July 2013. The Reserve Bank also took a number of administrative/

other measures to ease pressure on the rupee. Some of the key measures

included:

-

On July 8, 2013, banks were disallowed from carrying

proprietary trading in currency futures/exchange traded

options

-

To moderate the demand for gold for domestic use, measures

were taken to restrict import of gold by nominated agencies

on consignment basis on May 13 and June 4, 2013. On July

22, revised guidelines regarding import of gold by nominated

agencies was issued according to which at least 20 per cent of

every import of gold needs to be exclusively made available

for the purpose of export.

-

Special dollar swap window was opened for the PSU oil

Companies on August 28, 2013

-

Norms relating to rebooking of cancelled forward exchange

contracts for exporters and importers were relaxed on

September 4, 2013

-

A separate concessional swap window for attracting FCNR(B)

dollar funds was opened on September 4, 2013

-

Overseas borrowings limit was hiked from 50 per cent to

100 per cent of Tier I capital of the banks and concessional

swap facility with the Reserve Bank for borrowings mobilized

under the scheme was provided on September 4, 2013.

C. Outcome

The various measures taken by the RBI, both monetary as well

as administrative, lent some stability to the rupee with the rupee

exhibiting greater two way movements and stabilizing around the

level of 62 - 63 per US dollar in the second half of September 2013

and around 61-62 level during October 2013. The rupee has been

range-bound since then and has exhibited some strengthening bias

in the recent period, especially in March 2014. The stability of the rupee in the medium-term will depend on both external as well

as internal developments. The initial set of monetary tightening

measures taken on July 15, 2013 led to some strengthening of the

rupee vis-à-vis the US dollar. However, despite additional set of

monetary measures taken on July 23, 2013, the rupee continued

with its depreciating trend and touched historic lows during

August 2013. The rupee, based on RBI reference rate, appreciated

marginally by 0.6 per cent from 60.05 on July 15, 2013 to 59.69

per US dollar on September 23, 2013. However, despite RBI’s

monetary measures, the rupee depreciated continuously and touched

historic low of 68.85 per US dollar on August 28, 2013, a sharp

depreciation of around 13.3 per cent between July 23 and August

28, 2013. However, opening of dollar swap window for oil PSUs

on August 28, 2013 and announcement of additional measures by

the new Governor, Dr. Raghuram Rajan on September 4, 2013,

which inter alia included relaxation in rebooking of cancelled

forward contracts, concessional swap window for attracting FCNR

(B) deposits and enhancement in overseas borrowing limits of ADs

buoyed the market sentiment and reduced pressure on the rupee.

Positive domestic factors, such as, significant narrowing of trade

deficit in August 2013 on the back of rising exports, aided to some

extent by the sharp depreciation of the rupee against the US dollar,

and fall in imports, especially gold imports, turnaround in industrial

production for July 2013, improvement in CPI inflation rate, etc.,

coupled with positive external developments like deferment of

QE tapering by the US Fed in its FOMC meeting on September

18, 2013, easing of geopolitical tension over Syria and resolution

of the US budget impasse also aided the market sentiment, as a

result of which the rupee made a smart turnaround and appreciated

by 11.4 per cent to 61.81 per US dollar on September 27, 2013

from its historic low of 68.85 per US dollar on August 28, 2013,

indicating significant improvement in market sentiments.

The rupee has been range-bound and has exhibited strengthening

bias in the recent period on the back of sustained capital inflows.

The rupee has moved in the range of 59.65 and 63.65 per US

dollar during the period from mid-September 2013 to April 2, 2014. Despite the announcement on December 18, 2013 of

commencement of tapering by the US Fed starting from January

2014 and the subsequent announcements about the increase in its

pace, the rupee has generally remained stable, which indicates

that the markets have shrugged off QE tapering fears. The rupee

has remained relatively stable as compared to other major EME

currencies like Brazilian real, Turkish lira South African rand,

Indonesia rupiah and Russian rouble. The contagion effect of sharp

fall in Argentina peso against the US dollar in the second half of

January 2014 and the recent crisis in Ukraine also did not have any

major impact on the rupee.

Recent economic developments, such as, continued FII inflows

to the domestic equity markets and resumption of FII flows to

debt market as well, especially since December 2013 coupled

with substantial reduction in gold imports and increase in exports

leading to significant reduction in current account deficit to 0.9 per

cent of GDP in Q3 of 2013-14 have buoyed the market sentiment

and contributed to the stability of the rupee in the recent months.

As per RBI’s estimates, CAD narrowed to 1.7 per cent of GDP in

2013-14 from 4.7 per cent in 2012-13. The forex swap facilities

extended by the Reserve Bank along with enhancement in banks’

overseas borrowing limit, which led to forex inflows in excess of

US$ 34 billion, have bolstered forex reserves and aided the stability

of the rupee. Thus, a host of factors have led to the stability of the

rupee in the recent months.

The measures taken by the RBI, aided undoubtedly by both external

as well as internal positive developments, have had a stabilizing

impact on the forex market and have been successful in reversing

the unidirectional expectations of rupee’s depreciation.

Efficacy of Measures to contain the Recent Bout of Exchange Rate

Volatility and the Way Forward

The measures taken by the Reserve Bank have helped in stabilizing

the financial markets, in general, and the forex market, in particular. The

measures have been successful in countering the all pervasive negative

sentiment, which afflicted the markets during the period end-May to August 2013. The rupee staged a sharp turnaround in September 2013,

which continued in the subsequent months and also in Q1 of 2014. The

measures taken by the RBI (swap window for attracting FCNR (B) and

enhancement of overseas borrowing limits of banks) led to forex inflows

to the tune of US$ 34 billion, which helped in bridging the CAD during

2013-14. The measure to open special dollar swap window for oil PSUs

helped in removing a major chunk of demand from the forex market,

which went a long way towards stabilizing the rupee as bulk dollar

demand from oil PSUs is a major source of pressure on the rupee. These

measures buoyed the market sentiment, which got reflected in the sharp

turnaround made by the rupee from September 2014 onwards. Even

the monetary tightening measures taken by the RBI on July 15 and 23,

2013, which were subsequently relaxed in the mid-quarter review of

Monetary Policy on September 20, 2013, helped in reducing volatility

to an extent by making rupee expensive, thereby reducing speculation in

the forex market. Though monetary policy measures like hike in policy

rate is used by many central banks to attract capital, flows, its efficacy in

attracting greater capital flows is quite debatable. In this context, an RBI

Working Paper (May 2011) on ‘Sensitivity of capital flows to interest

rate differential’ has concluded that from the point of view of monetary

policy, FDI and FII flows are not impacted by interest rate changes

as they are primarily determined by growth prospects of the Indian

economy and returns on equities, respectively. During 2009-10, these

two, on a net basis, accounted for about 96 per cent of total net capital

inflows to India while for the 10-year period from 2000-01 to 2009-10,

they accounted for around 76 per cent of the total net capital flows.

The empirical results, however, corroborated the expectation that ECBs

and NRI deposits are interest sensitive, though policy interventions by

authorities do tend to reduce interest rate sensitivity. Thus, monetary

policy needs to take cognizance of the fact that debt flows like ECBs

and NRI deposits are impacted both by interest rate as well as exchange

rate movements, while sensitivity of capital flows like FDI and FII is

relatively less to interest rate changes.

The kind of intense volatility witnessed in the forex market during

May-August 2013 when the rupee experienced sharp depreciating

pressure is unlikely to recur anytime soon as the situation has improved significantly in the last 7 months. All the macro-economic parameters,

viz., current account deficit, fiscal deficit and inflation, which

contributed to the sharp depreciation of the rupee, have shown marked

improvement in the recent months. The stability of the rupee despite the

commencement of QE tapering and sharp depreciation in many EME

currencies bears testimony to the fact that the recent improvement in

fundamentals has stood the rupee in good stead. However, downside

risks in the form of still elevated retail inflation, continued weak

economic performance, uncertainty surrounding global economic

recovery, uncertainty surrounding capital flows to EMEs once QE is

completely withdrawn, etc., remain, which can cause intermittent

turbulence in the forex market.

Additionally, despite a sharp decline in CAD to a sustainable level

of 1.7 per cent of GDP in 2013-14 from 4.7 per cent in the previous

year, it remains to be seen if the positive momentum could be sustained

in the medium-to long-term, as this significant decline in CAD during

2013-14 has been mainly effected through a sharp compression in gold

imports through exceptional policy measures, including import duty

hike, taken by both the Government and the RBI, which may need to

be rolled back in due course. Thus, the need to bring the CAD down to

a sustainable level consistently for maintaining stable conditions in the

forex market needs no reiteration.

In this context, domestic structural factors, such as, inelastic

demand for POL and gold imports, which together account for a major

chunk of India’s imports coupled with large and increasing coal imports

despite India being one of the largest producers of coal in the world are

some of the important problems facing India’s external sector. Efforts

are already underway to reduce gold imports, deregulate POL pricing,

especially diesel prices, find new ways of increasing supply of POL

domestically through exploration and better use of existing facilities,

increase coal output in order to reduce imports, etc., which will have

a positive impact on CAD and, hence, on the exchange rate of the

rupee in the long-term. There is a need to increase and diversify India’s

exports and also to increase total factor productivity growth of India’s

exports in order to increase its competitiveness. A number of measures to address these important issues pertaining to structural transformation

of India’s external sector are already underway. The government and

the RBI have already taken a number of steps, such as, removal of

procedural bottlenecks, speedy clearance of FDI proposals, provision of

various incentives, pruning of negative list, etc., to facilitate FDI flows

to various sectors like FDI in retail, civil aviation, pension, insurance,

infrastructure sector, etc. All these measures, keeping in view the sound

economic fundamentals of the economy, should help in reducing the

CAD to sustainable levels in the medium-to long-term, thereby adding

significant strength to India’s external sector with concomitant stability

on the exchange rate front.

Apart from the measures that have already been taken, there are

talks about promoting invoicing of trade in domestic currency, which

has hitherto not been very successful. In this context, negotiating

bilateral currency swaps arrangements using domestic currencies with a

number of countries in the Asian region will give fillip to regional trade

and preclude the use of dollar for trade settlement purposes though such

a move will lead to internationalisation of the rupee, with its attendant

costs and benefits. India at present has swap arrangement with Japan to

the tune of US$ 50 billion, but that involves the use of dollar. China has

been aggressively internationalising renminbi since the onset of global

financial crisis and has successfully put in place swap agreements

involving local currencies with a number of countries (over 20 in

number) in the recent years and India can learn from their experience.

Governor Rajan in his statement on taking office on September 4, 2013

stated the following in regard to internationalization of the rupee: “As

our trade expands, we will push for more settlement in rupees. This

will also mean that we will have to open up our financial markets more

for those who receive rupees to invest it back in. We intend to continue

the path of steady liberalisation.’’ Thus, the issue of internationalisation

of the rupee in a careful and gradual manner needs to be taken up

proactively.

Section VIII

Concluding Observations

This paper has attempted to identify the major episodes of

volatility in Indian forex market in the past two decades, caused

either by exogenous or endogenous factors, or a combination of both.

The paper has attempted to capture the broad gamut of measures the

Reserve Bank has taken to effectively manage various episodes of

volatility in the past two decades. An analysis of the various episodes

of volatility in the Indian forex market reveals that there has been a

significant increase in exchange rate volatility in the aftermath of the

global financial crisis, signifying the greater influence of volatile capital

flows on exchange rate movements. An important aspect of the policy

response in India to the various episodes of volatility has been market

intervention combined with monetary and administrative measures to

meet the threats to financial stability while complementary or parallel

recourse has been taken to communications through speeches and press

releases.

In the end, structural problems present in India’s external sector,

especially the persistence of large trade and current account deficits,

will need to be addressed for a sustainable solution to the problem of

exchange rate volatility, as significant reliance on hot money in the