Balbir Kaur and Atri Mukherjee*

The objective of the paper is twofold. The first objective is to assess the sustainability of

public debt in India. In addition, an attempt has also been made to examine the relationship

between public debt and growth in the Indian context. The sustainability analysis, based on

empirical assessment of inter-temporal budget constraint and fiscal policy response function

at the general government level for the period 1980-81 to 2012-13, indicates that the debt

position in India is sustainable in the long run. The empirical results also reveal that there

is a statistically significant non-linear relationship between public debt and growth in India,

implying a negative impact of public debt on economic growth at higher levels. The threshold

level of general government debt-GDP ratio for India works out to be 61 per cent, beyond

which an inverse relationship is observed between debt and growth. This threshold level is

lower than the actual level of debt at 66.0 per cent of GDP in end March 2013. This calls for

a greater focus on a credible fiscal consolidation to safeguard against adverse debt dynamics

should the interest rate-growth differential turn less favourable, keeping in view the recent

slowdown in growth.

JEL Classification : H63, E62, O40

Keywords : public debt, gross fiscal deficit, growth

Introduction

The non-linear relationship between growth and debt has been

a subject of wide interest and debate since the time of publication

of the paper by Reinhart and Rogoff on the subject. In their paper

“Growth in a time of Debt” (2010), Reinhart and Rogoff (R&R) argue

that growth slows down sharply when the government debt to gross

domestic product (GDP) ratio exceeds a threshold level of 90 per cent.

The median growth falls by one per cent and the average growth falls by considerably more for debt-GDP ratios above the threshold of 90

per cent. The non-linear effect of debt on growth is considered to be

reminiscent of “debt intolerance” resulting in non-linear response of

market interest rates when debt tolerance levels are reached. These

results have been supported by a number of other studies (Kumar

and Woo, 2012; Cecchetti et al., 2011; Checherita and Rother, 2010

and Baum et al., 2012), although they differ, though not markedly, in

terms of the threshold level of debt-GDP ratio. Herdon, Ash and Pollin

(2013), however, point out that the conclusions of R&R may not hold

because of coding errors, selective exclusion of available data and

unconventional weighting of summary statistics in the methodology

used by the authors. After correcting for these statistical drawbacks,

they come to the conclusion that there is no evidence of a negative

relationship between debt and growth beyond the threshold level of 90

per cent.

Based on the most up-to-date work that incorporates the corrections

and latest set of data, R&R continue to hold that growth slows down

(by about 1 percentage point) when debt hits 90 per cent of GDP. In

other words, slower growth is associated with higher debt. However,

critiques1 are of the view that an association is definitely not a cause.

The direction of causality could be from growth to debt with slower

growth causing high debt. While this debate is still unsettled, this paper

seeks to test its validity, and estimate the threshold level of public debt

in India. In addition, the paper also provides a comprehensive analysis

of the sustainability of public debt in India through the use of different

approaches including inter-temporal budget constraint and fiscal policy

response function.

The paper is organised as follows. Section II provides a brief

description of various channels through which high public debt levels

are said to impact growth, inflation and other macroeconomic variables.

Section III presents a review of literature relating to determination of

threshold level of debt based on both debt-growth relationship and fiscal/

debt sustainability aspects. Section IV covers evolution of combined debt position of central and state governments in India from 1980-81

to 2012-13. It also analyses the impact of developments in the primary

balances along with interest rate and growth dynamics on the evolution

of public debt in India. Section V examines debt sustainability in the

Indian context in terms of various indicators of public debt sustainability,

inter-temporal budget constraint and fiscal policy response function of

the government. Section VI analyses the debt-growth relationship in

India. Concluding observations are covered in Section VII.

Section II

Interplay of High Public Debt and Macro-Economic Variables

Fiscal expansion financed through debt issuances and the resultant

public debt accumulation have important influences over the economy

both in the short-run as well as the long run. Debt per se may not be

bad. It depends on the utilisation of funds raised through borrowings.

In case it is used for capital formation, it could contribute to the real

income of future generation and add to repayment capacity of the

government as well. On the contrary, the use of borrowings to finance

only current expenditure poses the risk of debt rising to unsustainable

levels.

There are different channels through which elevated and rising

levels of public debt could operate and impact growth, viz., reduced

investment/capital accumulation following the pressure on longterm

interest rates (Baum et al., 2012), reduced (perceived) returns

on investment due to uncertainty about future prospects and policies,

and risk of introduction of distortionary taxes. Besides these, there

are other risk factors, such as, volatility in interest rates, reduced

present and future productive government spending, reduced scope for

countercyclical policies and vulnerabilities associated with debt buildup

that tend to contribute to slowdown in economic activity and growth

at higher levels of debt.

High public debt levels, through higher issuances of government

debt, crowd out private investment, in the absence of debt neutrality or

Ricardian equivalence, particularly when the economy is operating at

or near full employment situation. Pattillo et al., (2002) indicate that

the effect of debt on growth works through reduction in total factor productivity growth and physical capital accumulation. Cournede (2010)

points out the impact of high debt levels on cost of capital and in turn

on the intensity of capital in production. The lower productivity level

affects potential output and growth and the effect could be substantial

in case investment in research and development reduces in response to

higher cost of capital. Kumar and Woo (2012) also point argue that debt

accumulation has a larger adverse impact on domestic investment of

emerging market economies vis-a-vis advanced economies.

The persistence of debt overhang raises the risk of sovereign

insolvency, particularly during economic downturns. Higher the debt,

higher is the risk of repayment ability or probability of default which, in

turn, leads to widening of sovereign spreads, thereby making attainment

of debt sustainability all the more difficult to achieve. Moreover, higher

sovereign spreads get transmitted to higher private lending spreads,

affecting both investment and consumption.

High and rising public debt arising from unsustainable fiscal policies

also increases the risk of an eventual monetisation of persistent deficits,

with consequent impact on inflation. If the long-run interest rate-growth

rate differential turns positive, a higher debt-GDP ratio, for a given

primary deficit-GDP ratio, could increase the anticipated inflation tax

in the form of higher seigniorage revenue through increased issuance of

base money. It could also tempt the government to erode the real value of

current and future debt service through unanticipated burst of inflation,

with inflation having the largest impact on long-term, fixed-rate, and

local-currency denominated debt. Fear of the government inflating

away a part or the whole of its domestic currency denominated debt

burden in future could lead to a rise in nominal interest rates associated

with higher inflationary expectations and higher inflation risk premium

(Buiter and Patel, 2010).

In emerging markets, high public debt levels tend to generate

significant inflationary pressures. R&R (2010) point out that median

inflation more than doubles (from less than seven per cent to 16 per

cent), as debt in emerging markets rises from the low range of 0-30 per

cent to above 90 per cent. The existence of a strong and stable impact of debt growth on inflation in developing and some advanced economies

establishes the indirect negative impact of debt on growth in these

countries.

Section III

Review of Literature

In the theoretical and empirical literature, the threshold level of

debt has been defined based on two strands of thought viz., debt-growth

dynamics and fiscal/debt sustainability perspective in different countries

over a period of time. In terms of debt-growth dynamics, increases in

debt-GDP ratio beyond the threshold level are associated with a negative

impact on growth, while they give rise to debt servicing, liquidity and

solvency concerns from the view point of debt sustainability.

The recent empirical studies have primarily focused on the debtgrowth

relationship and been motivated by the R&R’s (2010) work,

raising concerns regarding negative impact of debt on growth when

debt-GDP ratio exceeds the threshold level of 90 per cent. Baum

et al. (2012) and Chang and Chiang (2009) have looked at the impact

of debt on short-term growth, while the focus of other studies is on

medium-term/long-run economic growth. The short-term growth

effect is studied in terms of either direct impact of debt on growth or

indirect impact running through fiscal multipliers linked to shocks to

government expenditure or taxes while also being influenced by the

initial level of debt.

Reinhart and Rogoff (2010) show that growth rates in both

developed and developing countries with the public debt to GDP ratio

higher than 90 per cent are about 1 percentage point lower than in the

less indebted countries. Growth in emerging markets (EMs) slows down

by an annual two percentage points when their external debt reaches 60

per cent of GDP and the decline is even sharper for external debt levels

in excess of 90 per cent of GDP. Other empirical studies also establish

that public debt beyond a certain threshold is negatively correlated

with economic growth (Egert, 2012; Elmeskov & Sutherland, 2012;

Greenidge et al., 2012; Kumar & Woo, 2012; Cecchetti et al., 2011;

Checherita & Rother, 2010; Baum et al., 2012; Cordella et al., 2005).

The negative effect of debt on growth is attributed, among others, to both the crowding out effect and the debt overhang effect. However,

the direction of causality has not been unambiguously established.

Elmeskov and Sutherland (2012) admit that high debt levels have a

negative impact on growth but they argue that correlation is not the same

as causation. While high levels of public debt could be detrimental to

growth, low economic growth could itself lead to high levels of public

debt i.e., reverse causality. Easterly (2001) argues that the causality

runs from growth to debt. In the Indian context, while Singh (1999)

found that the domestic debt held by the public and economic growth

are not causally related, Rangarajan and Srivastava (2005) indicate

that growth may be adversely impacted on account of large structural

primary deficit and interest payments relative to GDP.

The non-linearity in the impact of debt on growth has been

examined in empirical studies based on various model specifications.

Reinhart and Rogoff (2010) use correlations between debt and growth

while Kumar and Woo (2012) and Egert (2012) study the impact of

public debt on growth along with other determinants of growth in a

general growth framework. The statistical techniques used in empirical

exercises include OLS, quadratic, spline and panel regressions, besides

using exogenously/endogenously determined threshold debt levels

and calculating debt thresholds based on credit ratings of major rating

agencies2. The threshold level of debt varies for different regions/

country groups as also across countries.

The determination of public debt thresholds, based on the

concept of sustainable public debt level, has primarily been guided by

necessary and sufficient conditions of debt sustainability as defined in

the theoretical literature. In the pioneering work on debt sustainability,

Domar (1944) said that GDP should grow faster than public debt for

debt to be sustainable. Subsequently, Buiter et al. (1985) suggested that

sustainable fiscal policy is the one that is capable of keeping the public

sector net worth to output ratio at its current level. Blanchard et al.

(1990) introdicate two conditions for a sustainable fiscal policy: (i) the

ratio of debt to GNP should converge in the long run to its initial level, and (ii) the present discounted value of the ratio of primary budget

deficit to GNP should be equal to the negative of the current level of

debt to GNP.

The debt sustainability conditions revolve around the government’s

inter-temporal or the present value budget constraint (PVBC). This

has been put differently in various empirical studies. In Lengrenzi and

Milas (2011) work, the PVBC requires that the present value of outlays

(current and future) equals the present value of revenues (current and

future). The transversality condition under the PVBC constrains the

debt to grow at a slower rate than the interest rate (Chalk and Hemming,

2000). Buiter and Patel (2010) refer to the standard solvency constraints

viz., (i) the present discounted value of the terminal government nonmonetary

debt be non-positive and (ii) the outstanding value of the

government’s non-monetary debt cannot exceed the present discounted

value of its future primary surpluses. In terms of the first constraint, the

growth rate of public debt cannot be greater than the effective interest rate

on the public debt. Gerson and Nellor (1997) define fiscal sustainability

as a situation of overall fiscal balance rather than a constant debt ratio.

In the Indian context, the sustainability of public debt has been

empirically examined based on various approaches including the Domar

stability condition and time series methods, such as, stationarity of debt

series, unit root and co-integration tests. While the earlier studies of the

1990s (Buiter and Patel, 1992, 1995; Jha, 1999 and Cashin and Olekalns,

2000) drew attention to non-stationarity of debt series and violation of

solvency conditions/inter-temporal budget constraint, the subsequent

studies based on the co-integration and other techniques have admitted

a weakly sustainable condition or sustainable public debt situation (Jha

and Sharma, 2004). After addressing the issue of regime shift, Goyal,

Khundrakpam and Ray (2004) find that while fiscal stance of the

central and state governments at the individual level is unsustainable,

it is weakly sustainable for the combined finances of centre and states.

Some of these studies indicate that the stationarity - based sustainability

tests are satisfied when structural or regime-based breaks in debt-GDP

series are accounted for. Tronzano (2012) finds the existence of firstorder

cointegration between revenue and expenditure flows but could not confirm the existence of a deeper long-run equilibrium between

stock and flow fiscal variables and cautioned that an adverse shock on

the real economy may destabilise the debt pattern in India.

Bohn (2008) argues that the failure of stationarity and co-integration

could not be interpreted as evidence of unsustainable fiscal policy.

The time series tests are backward looking and do not fully exploit

the implications of uncertainty in deriving appropriate tests of fiscal

sustainability. He suggests that the positive response of primary balance

relative to GDP to public debt relative to GDP of a country be considered

as an indicator of dynamic sustainability3. Using this framework and

Fincke and Greiner’s model of time-varying coefficients4 for testing

public debt sustainability, Tiwari (2012) did not find any clear-cut

evidence on the sustainability of public debt in India during the period

1970-2009.

Section IV

Debt Dynamics in India

IV.1: Evolution of India’s Public Debt5

The fiscal position of the central and state governments had

remained comfortable in the first three decades since Independence.

The revenue account of the central government turned into deficit in

the year 1979-80, while the state finances exhibited signs of fiscal

stress since the mid-1980s. Given this backdrop, both the centre and

states started with moderate debt levels, with the consolidated public

debt to GDP ratio at 47.9 per cent in end March 1981. However, the

debt position deteriorated steadily thereafter to reach a high of 72.9

per cent in end March 1992. This was also the period characterised by

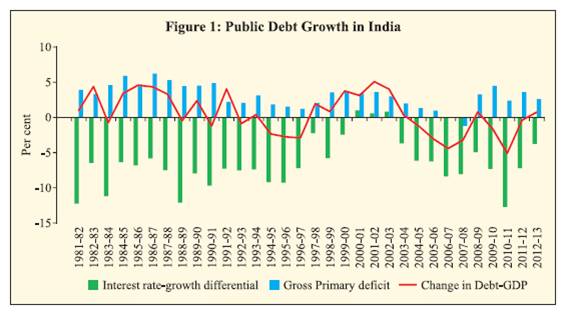

high primary deficits with the primary deficit-GDP ratio at 6.2 per cent in 1986-87 (Figure 1), giving rise to concerns regarding high growth

in public debt of India (Seshan, 1987; Report of the Comptroller and

Auditor General of India, 1988).

There was some improvement in debt position during the period

1992-93 to 1997-98, which reflected the impact of macro-economic

and structural reforms undertaken in the aftermath of the balance of

payments crisis in the early 1990s. However, this improvement could

not be sustained, as all the key deficit indicators of the central and

state governments deteriorated sharply thereafter, due to additional

expenditure liabilities linked to the implementation of the Fifth Pay

Commission award as also sluggish revenue growth on account of

poor performance of public sector undertakings. Reflecting these

developments, the debt liabilities accumulated sharply and the public

debt-GDP ratio increased to 83.2 per cent in end March 2004.

IV.2: Fiscal Consolidation and Public Debt Growth

Fiscal reforms at the central government level were led by the

enactment of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM)

Act, 2003. Around the same time, most states also operationalised fiscal

rules with a focus on a phased improvement in their fiscal deficit and debtgross

state domestic product (debt-GSDP) ratios. The state government

initiatives were also supported by the implementation of Debt Swap Scheme (DSS) from 2002-03 to 2004-05 and Debt Consolidation and

Relief Facility (DCRF) from 2005-06 to 2009-10. While the DSS

allowed the state governments to pre-pay their high cost loans from

the central government, the DCRF provided for debt consolidation and

debt/interest relief on outstanding central government loans, subject to

the enactment of the FRBM Act and reduction in revenue deficit, as per

stipulated rules, during the award period. As a result of these measures,

the outstanding debt-GDP ratio of the states at the consolidated level

declined from 31.8 per cent in end March 2004 to 26.6 per cent in end

March 2008. A similar improvement was evident in debt position of

the central government. This trend has continued thereafter (barring

2008-09) with the public debt-GDP ratio of the general government

(central and state governments) declining to 66.0 per cent in end March

2013.

IV.3 Features of Public Debt in India

It is important to analyse the composition, ownership, and maturity

pattern of public debt that provide an idea about liquidity and pricing

risks associated with the level of debt and its profile. In the Indian

context, the central government debt accounts for around 70 per cent

of the total public debt of the general government. Within public debt,

domestic/internal liabilities remain the predominant component, with

external debt accounting for less than 3 per cent of the total public debt

(Annex Table A.1). Market loans of the central and state governments

account for over 50 per cent of the total public debt in India.

As regards ownership pattern of central and state government

securities, more than 50 per cent of these securities are held by the

scheduled commercial banks, reflective of the mandatory statutory

liquidity reserve requirements. Insurance companies hold about 20 per

cent of these securities (Annex Table A.2). Notwithstanding an increase

in the share of short-term debt in the recent period, it accounts for less

than 10 per cent of the total public debt in India (Annex Table A.3).

The long maturity profile of India’s public debt along with a small

share of floating rate debt (less than 5 per cent) tends to limit rollover

risks, and insulate the debt portfolio from interest rate volatility (Annex

Table A.4).

IV.4: Inflation and Interest Rates: Impact on Public Debt

The declining debt levels across countries during the 1970s were

attributed to the negative real interest rates following high inflation

rates in these countries (Hall and Sargent 2011). In the context of EMs,

empirical studies refer to the phenomenon of the government inflating

away a part or the whole of its domestic currency denominated debt

burden in future, in case financial markets are characterised by financial

repression. Financial repression refers to a set of government policies

that keep the real interest rates low or negative than would otherwise

prevail, for the purpose of reducing the interest burden on government

debt. An environment of low or negative real interest rates, characterised

as financial repression, can be achieved either through lower nominal

interest rates or through higher inflation rate or through a combination

of the two (Reinhart and Sbrancia, 2011). The negative real interest

rates help to liquidate or erode the real value of government debt. The

year, in which the real interest rate turns negative, is considered as a

liquidation year. During the liquidation years, the negative real interest

rate on government debt generates savings to the government, which is

also known as financial repression revenue.

In this section, following the methodology of Reinhart and

Sbrancia (2011), an attempt has been made to examine the presence

of financial repression in the Indian context and if so, its benefit to the

government in terms of lower interest burden. The time period covered

for the analysis is 1982-83 to 2012-13. For this purpose, the real interest

rate in India has been worked out using the Fisher equation such that:

r t = (1+i t-1) / (1+π t) -1

Where i = nominal interest rate; r = real interest rate; and

π = inflation rate. Effective interest rate on general government debt

has been used as a proxy for nominal interest rate. Inflation rates have

been measured in terms of GDP deflator. The calculations reveal that

real interest rates in India were negative during the period 1982-83 to

1995-96 but turned positive thereafter. The real interest rate has again

turned negative in the recent period (Figure 2). The years marked by

negative real interest rates are considered as liquidation years.

The savings/revenues to the government during these years through

liquidation effect are measured in terms of real interest rate times the

stock of outstanding debt of the government. The financial repression

revenues, thus calculated, are expressed as a share of GDP as well as a

share of tax revenues (Table 1).

It may be observed from Table 1 that in India, during the period

1982-83 to 1995-96, the annual liquidation of debt via negative real

interest rates amounted to 1.5 per cent of GDP and 10.3 per cent of the

tax revenues of the government6. Annual debt reduction of 1.5 per cent

of GDP accumulates to around 21.2 per cent reduction in the debt to

GDP ratio during this period7.

Table 1: Government Revenue from Liquidation Effect |

(per year) |

Period |

Financial Repression

Revenues/GDP (%) |

Financial Repression

Revenues/Tax Revenues (%) |

1982-83 to 1995-96 |

1.5 |

10.3 |

1996-97 to 2007-08 |

-2.5 |

-17.0 |

2008-09 to 2012-13 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

Following a gradual development of market-based instruments

to finance government deficits, move towards a market-determined

interest rate system through auction of government securities, phasing

out of the automatic monetisation of fiscal deficit through the two

Supplemental Agreements between the Government and the Reserve

Bank and discontinuation of the Reserve Bank’s subscription to primary

issuances of government securities from April 1, 2006, the liquidation

effect ceased to exist during the period 1996-97 to 2007-08, when

the real interest rates turned positive. During the last 5 years (except

2009-10), the real interest rate has again turned negative, despite sharp

increases in market borrowings of the central government. The annual

financial repression revenue accruing to the government was, however,

of much smaller magnitude at 0.1 per cent of GDP and 0.3 per cent of

tax revenues during this period.

IV.5: Growth and Interest Differentials: Impact on Public Debt

The growth of public debt in nominal terms depends on two

parameters, viz., interest rate on public debt and the size of the primary

surplus/deficit. In case the primary balance is in deficit, both interest

liabilities and primary deficits contribute to accumulation of additional

debt liabilities in any economy. However, when public debt relative to

GDP is considered, its evolution also depends on an additional variable

i.e., the growth-interest rate differential. This implies that in case the

interest rate is lower than the growth rate of the economy, it helps

to offset the impact of primary deficit on debt growth and it may be

possible to keep debt to GDP ratio stable even in a situation of primary

deficits.

Theoretically, in case the real (nominal) rate of interest is lower than

the rate of growth of real (nominal) GDP, the debt stabilising primary

balance can be negative8. However, it is desirable that government

primary expenditure minus government revenue as a proportion to GDP

is less than or equal to zero, on an average, so that the debt burden is

ultimately liquidated.

In the Indian context, it has been observed that the favourable

growth-interest rate differential has muted the impact of persistence

of primary deficits on public debt-GDP ratio (Table 2). Rangarajan

and Srivastava (2003, 2005) in their study covering the period

1955-2000 find that even with persistence of primary deficits for a long

period of time, the debt to GDP ratio could be contained in India as the

GDP growth exceeded the interest rates. Available data shows that the

primary surplus was recorded only in two years: 2006-07 and 2007-

08. Considering the fact that the interest rate - growth rate differential

has gradually narrowed down with a progressive move towards market

determination of yields on government debt issuances and given the

difficulties in sustaining high rates of growth, it would be challenging to

maintain fiscal/debt sustainability in absence of a turnaround in primary

balance position in the medium to long run.

IV.6: Public Debt in India vis-a-vis Other Country Groups

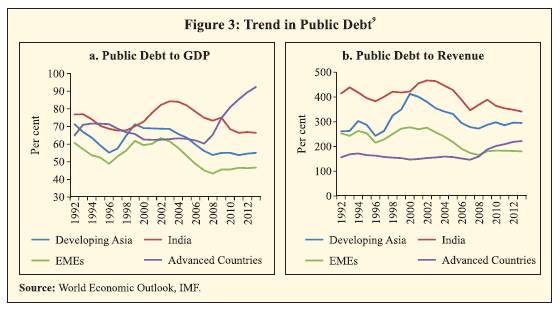

Public Debt in India (as a per cent to GDP) has witnessed a steady

decline since 2004, aided, in large part, by the FRBM Act 2003 of

the central government and similar fiscal responsibility legislations

at the state level and high nominal GDP growth vis-à-vis incremental

debt. Although fiscal deficit to GDP ratio increased in 2008-09 and 2009-10 due to counter-cyclical measures taken by the government to

insulate Indian economy from the adverse impact of global economic

crisis, the declining trend in debt-GDP ratio was maintained, which

was largely supported by higher nominal GDP growth up to 2011-12.

In 2012-13, with the nominal GDP growth in India falling below the

growth in public debt, the debt-GDP ratio increased again. India’s

public debt - GDP ratio has, in general, been significantly higher than

the average for emerging markets, developing Asia and advanced

economies (Figure 3a).

Table 2: Decomposition of Debt Accumulation Relative to GDP |

(per cent) |

|

Changes in

Debt-GDP ratio |

Cumulative

Primary

deficit-

GDP ratio |

Cumulative

Interest rate

and Growth

differential |

1980-81 to 1989-90 |

22.13 |

48.01 |

-38.34 |

1990-91 to1999-00 |

2.00 |

26.15 |

-41.03 |

2000-01 to 2009-10 |

-3.36 |

20.87 |

-28.66 |

2010-11 to 2012-13 |

0.46 |

8.58 |

-13.70 |

Memo: |

|

|

|

Debt-GDP Ratio at the end of |

|

|

|

1980-81 |

47.94 |

|

|

2012-13 |

66.00 |

|

|

Source: Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, RBI, and National Accounts Statistics,

CSO. |

Public debt to government revenue ratio, which is a useful indicator

of the vulnerability of a country’s public finances and the solvency of

the government, shows that India’s public debt as a ratio to revenue

is very high, although it has declined during the recent period (Figure

3b). So, the country’s capacity to support high levels of public debt is

constrained by its ability to raise revenues.

A comparison of debt and other fiscal indicators across major

emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) suggests that

India is an outlier in almost all parameters. Countries which have high

debt-GDP ratio, such as, Brazil and Hungary have a lower debt-revenue

ratio than India (Table 3).

Table 3: Fiscal Indicators for Select Emerging Market Economies |

(Per cent) |

Countries |

2006 |

2012 |

2013 |

Debt-

GDP |

Debt-

Revenue |

Overall

Balance-

GDP |

Primary

Balance-

GDP |

Debt-

GDP |

Debt-

Revenue |

Overall

Balance-

GDP |

Primary

Balance-

GDP |

Debt-

GDP |

Debt-

Revenue |

Overall

Balance-

GDP |

Primary

Balance-

GDP |

Argentina |

76.4 |

256.4 |

-1.1 |

4.0 |

47.7 |

118.7 |

-4.3 |

-0.9 |

47.8 |

114.6 |

-3.6 |

-1.3 |

Brazil |

67.0 |

193.6 |

-3.5 |

3.3 |

68.0 |

180.4 |

-2.7 |

2.2 |

68.2 |

183.8 |

-3.0 |

1.9 |

China |

16.2 |

89.0 |

-0.7 |

-0.2 |

26.1 |

115.0 |

-2.2 |

-1.4 |

22.9 |

103.2 |

-2.5 |

-1.8 |

Colombia |

36.8 |

134.8 |

|

1.7 |

32.8 |

115.9 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

32.5 |

115.7 |

-1.0 |

0.7 |

Egypt |

90.3 |

315.7 |

-9.2 |

-4.2 |

80.6 |

356.6 |

-10.7 |

-5.2 |

88.7 |

371.1 |

-14.7 |

-7.3 |

Hungary |

65.9 |

154.0 |

-9.4 |

-5.7 |

79.2 |

170.3 |

-2.0 |

2.0 |

79.8 |

167.6 |

-2.7 |

1.2 |

India |

77.1 |

379.8 |

-6.2 |

-1.3 |

66.7 |

343.8 |

-8.0 |

-3.6 |

67.2 |

342.9 |

-8.5 |

-3.8 |

Indonesia |

39.0 |

192.1 |

0.2 |

2.6 |

24.0 |

134.8 |

-1.7 |

-0.4 |

25.8 |

142.5 |

-2.2 |

-0.8 |

Malaysia |

41.5 |

172.2 |

-2.7 |

-1.7 |

55.5 |

219.4 |

-4.5 |

-3.1 |

57.1 |

229.3 |

-4.3 |

-3.0 |

Mexico |

37.8 |

175.0 |

-1.0 |

1.8 |

43.5 |

184.3 |

-3.7 |

-1.2 |

43.6 |

193.8 |

-3.8 |

-1.2 |

Pakistan |

54.4 |

400.0 |

-3.4 |

-0.5 |

63.8 |

487.0 |

-8.4 |

-4.0 |

66.5 |

503.8 |

-8.5 |

-3.9 |

Peru |

33.1 |

164.7 |

1.9 |

3.7 |

20.5 |

94.5 |

2.1 |

3.0 |

18.3 |

88.4 |

0.3 |

1.1 |

Philippines |

51.6 |

271.6 |

0.0 |

4.8 |

41.9 |

234.1 |

-0.9 |

1.7 |

41.0 |

226.5 |

-0.8 |

1.8 |

Poland |

47.7 |

118.7 |

-3.6 |

-1.0 |

55.6 |

144.8 |

-3.9 |

-1.1 |

57.8 |

157.1 |

-4.6 |

-1.9 |

Russia |

9.0 |

22.8 |

8.3 |

8.9 |

12.5 |

33.9 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

13.8 |

37.5 |

-0.7 |

-0.2 |

South Africa |

32.6 |

111.6 |

1.2 |

4.1 |

42.3 |

151.6 |

-4.8 |

-2.1 |

43.0 |

154.7 |

-4.9 |

-2.1 |

Thailand |

42.0 |

188.3 |

2.2 |

3.5 |

45.4 |

197.4 |

-1.7 |

-0.8 |

47.2 |

219.5 |

-2.7 |

-2.2 |

Turkey |

46.5 |

141.8 |

-0.7 |

4.4 |

36.1 |

103.7 |

-1.6 |

1.2 |

36.1 |

99.7 |

-2.3 |

0.7 |

Source: World Economic Outlook Database and Fiscal Monitor, 2013, International Monetary Fund. |

Section V

Public Debt Sustainability

Sustainable level of public debt varies across different countries

depending on the country-specific circumstances. Besides the magnitude

of debt, the characteristics of public debt – currency composition,

maturity pattern and debt servicing at fixed or floating rates – also

contribute significantly to determining the sustainable level of debt.

This section looks at public debt sustainability in the Indian context,

based on different approaches to assessment of sustainability of public

debt.

V.1: Indicator Analysis

Following the conventional debt sustainability analysis, the

sustainability of public debt in India has been examined using indicator

analysis, taking period averages of various indicators during four

different phases (Table 4). These phases have been identified on the

basis of the inflexion points in the general government debt. Phases I and

III witnessed distinct pressure on debt sustainability, with the average

nominal public debt growth exceeding the average nominal GDP

growth during these periods. The stability condition which requires the real interest rate to remain below the real output growth, was, however,

satisfied in all the four phases.

Table 4: Fiscal Sustainability of General Government :

Indicator-based Analysis |

Sl.

No. |

Indicators |

Symbolic

Represe ntation |

Phase-I

(1981-82

to

1991-92) |

Phase II

(1992-93

to

1996-97) |

Phase III

(1997-98

to

2003-04) |

Phase IV

(2004-05

to

2012-13) |

1 |

Rate of growth of public debt (D) should be lower than rate of growth of nominal GDP (G) |

D - G < 0 |

4.45 |

- 2.84 |

4.14 |

- 2.98 |

2 |

Rate of growth of public debt (D) should be lower than effective interest rate (i) |

D - i < 0 |

12.94 |

5.26 |

5.82 |

4.21 |

3 |

Real rate of interest (r) should be lower than real output growth (g) |

r - g < 0 |

-7.67 |

-7.58 |

-1.57 |

-6.67 |

4(a) |

Primary balance (PB) should be in surplus |

PB / G > 0 |

-0.05 |

-0.02 |

-0.03 |

-0.02 |

4(b) |

Primary revenue balance (PRB) |

PRB / G > 0 |

-0.01 |

-0.01 |

0.00 |

-0.02 |

|

should be in surplus and should be adequate enough to cover interest payments (IP) |

PRB/IP>100 |

-42.93 |

-29.05 |

3.47 |

-36.42 |

5(a) |

Revenue Receipts (RR) as a per cent to GDP should increase over time |

RR/ G ↑↑ |

18.41 |

17.76 |

17.22 |

19.86 |

5(b) |

Revenue variability should decline over time |

CV (RR/G) ↓↓ |

4.86 |

2.54 |

4.40 |

4.31 |

5(c) |

Public debt to revenue receipts ratio should decline over time |

D / RR ↓↓ |

3.37 |

3.90 |

4.34 |

3.63 |

5(d) |

Public debt to tax revenue ratio should decline over time |

D / TR ↓↓ |

4.22 |

4.88 |

5.41 |

4.45 |

6(a) |

Interest burden defined by interest payments (IP) as a per cent to GDP should decline over time |

IP / G ↓↓ |

3.28 |

4.86 |

5.71 |

5.06 |

6(b) |

Interest payments (IP) as a per cent of revenue expenditure (RE) should decline over time |

IP / RE ↓↓ |

15.84 |

22.92 |

24.66 |

22.10 |

6(c) |

Interest payments (IP) as a per cent of revenue receipts (RR) should decline over time |

IP / RR ↓↓ |

17.72 |

27.38 |

33.13 |

25.54 |

The necessary conditions for sustainability as given in indicators 1

and 3 of Table 4 were fulfilled during the periods of fiscal consolidation,

viz., phases II and IV, but the sufficient condition of generating

primary surpluses was not met during any of the four phases. In fact,

with the exception of 2006-07 and 2007-08, primary balances of the

general government remained in deficit during the last three decades

(Figure 4). Favourable interest rate-growth differential has, however,

more than compensated for the absence of primary surpluses, resulting

in a sharp decline in debt-GDP ratio between 2004-05 and 2010-11,

barring a brief increase in the immediate aftermath of the global financial

crisis. With a decline in the interest rate-growth differential and an

increase in primary deficits, the growth in public debt has increased in

2012-13.

Although the debt-GDP ratio declined in phase II reflecting the

impact of reforms, debt sustainability indicators in terms of debt service

burden (as expressed by indicators 5 and 6 in Table 4) deteriorated.

There was a regime shift from large dependence on monetised

financing (through the issuance of 91-day Treasury bills (T-bills)) to bond financing, resulting in a rise in the average effective cost of

debt during this phase. This was also evident from the decline in the

share of T-bills (91-day and 182/364-day T-bills) in outstanding debt

of central government to 6.6 per cent in phase II (from 10.5 per cent in

phase 1). The debt service burden deteriorated further in phase III as it

was characterised by an up-trend in interest rates. However, this trend

reversed in phase IV due to the combined impact of improvement in

revenue buoyancy and reduction in interest rates from the highs seen

in the 1990s and early 2000s. The average interest payments have,

however, continued to pre-empt around one-fourth of revenue receipts

during phase IV, which is higher than the tolerable ratio of interest

burden10. The high level of incremental debt which was acquired during

2008-09 and 2009-10 has contributed significantly to the rising interest

burden in recent years.

Post-crisis fiscal correction in India had been slow and the observed

improvement in 2010-11 was primarily due to large one-off receipts

from spectrum auctions. The central government has, however, reverted

to a revised path of medium-term fiscal consolidation in line with the

Kelkar Committee recommendations in 2012-13. A progressive move

towards fiscal sustainability, if maintained, would facilitate further improvement in the public debt-GDP ratio. This would be more credible

and sustainable from the viewpoint of debt sustainability in case it is

driven by the objective of achievement of primary surpluses.

V.2: Inter-temporal Budget Constraint

Going beyond the indicator - based analysis, the fiscal/debt

sustainability issue has been examined empirically through the

assessment of inter-temporal government budget constraint. In the

empirical work, this is analysed through test of stationarity properties

of the government debt stock (in level and first difference), examination

of the long-term relationship between government revenues and

expenditures and that between primary balances and debt.

In this Section, we have made an attempt to test empirically,

whether India’s fiscal policy stance is sustainable, i.e., whether it

satisfies the inter-temporal budget constraint. This test of fiscal policy

sustainability examines whether the past behaviour of government

revenue, expenditure and the fiscal deficit could be continued indefinitely

without prompting an adverse response from the investors who finance

government borrowings. The inter-temporal budget constraint as

derived by Cashin and Olekalns (2000) is as follows:

Where G is government expenditure including interest payments,

R is government revenue, B is the stock of debt, and r is the real rate

of interest. The inter-temporal budget constraint, under the assumption

that the funding of interest payments are not made from the new debt

issuances (i.e., no-ponzi scheme), imposes restrictions on the time

series properties of government expenditures and revenues. This

requires that government expenditure, revenue and stock of debt are all

stationary in the first differences. The stationarity property also restricts

the extent of deviation of Gt from Rt over time. In case Gt and Rt are

I (1) and cointegrated, then the error correction mechanism would push

government finances towards the level required by the inter-temporal

budget constraint and ensure fiscal and debt sustainability in the long

term.

The stationarity properties of the stock of government debt,

government expenditure and revenues in the Indian context have been tested using annual data for the period 1980-81 to 2012-13. The variables

have been converted into real terms with logarithmic transformation.

The results of the Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) unit root test

indicate that the null hypothesis of unit root cannot be rejected for all

the three variables. It was also found that all the series are integrated of

order 1, i.e., stationary in the first difference (Table 5).

Since log Rt and log Gt were found to be I (1), the cointegration

between the two series has been tested through the standard Engle

and Granger’s (1987) procedure. Following Hakkio and Rush (1991),

cointegration between log Rt and log Gt is tested by estimating the

regression:

Log (Rt) = α + β log (Gt) + ε t, where 0 < β ≤ 1

Cointegration requires that residuals from the above equation are

stationary. The equation is estimated using simple OLS. The residuals

series obtained from the estimated equation was found to be stationary

I(0)11. Thus, the two series, viz., log Rt and log Gt were found to be

cointegrated indicating a long-term co-movement between the two series

and suggesting that the current fiscal policies in India are sustainable

in the long run. This result is also supported by the study of Jha and

Sharma (2004)12.

Table 5: Unit Root Test |

Variable (X) |

ADF |

Log X |

D log (X) |

Stock of Government Debt (B) |

-0.90 |

-3.71* |

Government Expenditure (G) |

0.65 |

-5.20* |

Government Revenue (R) |

0.86 |

-5.52* |

Note: * denotes significant at 1% level. |

V.3: Fiscal Policy Response Function

The time series tests of fiscal sustainability have been criticised in

the empirical literature for not explicitly identifying the fiscal policy

reaction functions that underlie the data. Bohn (1995, 1998), therefore,

suggested an alternative model-based approach to fiscal sustainability.

This approach looks at the inter-temporal budget constraint in terms of a

feedback relationship from the stock of initial debt to the primary surplus

in an economy characterised by risk-averse lenders and uncertainty. In

this fiscal reaction function approach, it is analysed whether primary

surplus relative to GDP is a positive function of public debt (relative to

GDP). In case fiscal authorities take corrective measures in response to

deterioration in debt position, rising debt ratios lead to higher primary

surpluses relative to GDP that indicates a tendency towards mean

reversion. According to Bohn, a stable and strictly positive feedback

from debt stock to primary surplus is a sufficient condition for fiscal

(debt) sustainability. We have also used this approach in the following

analysis.

Model Specification: The following equation is estimated:

St = α 0 + β D t-1 + α1 GDPGAP t + α2 EXPGAP t + ε

Here S is the primary surplus to GDP ratio; D is the public debt to

GDP ratio; GDPGAP is the deviation of actual output from the trend;

EXPGAP is the deviation of actual primary expenditure from the trend;

and ε is the error term. The business cycle variable GDPGAP has

been included to account for the fluctuations in revenues. The variable

EXPGAP captures the impact of deviations of real primary expenditure

from its long-term trend on the primary surplus ratio. Here ‘β’ is the key

coefficient, which measures the response of primary surplus to debt.

A value of this coefficient between zero and unity is consistent with a

sustainable fiscal policy response to debt. A negative coefficient implies

potentially destabilising response.

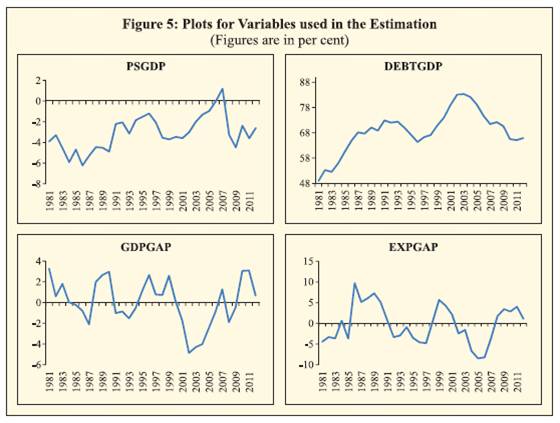

Data: Annual data for the period 1981-82 to 2012-13 has been used

for the analysis. All the data pertain to the general government (centre

and states combined). Primary balance of the general government has

been considered as the dependent variable. Combined liabilities of the

central and state governments have been used to represent public debt

of India. GDP at market prices has been used for the analysis. GDPGAP

has been worked out by extracting the deviation in real GDP from its trend through HP-filter. The deviation is expressed as a per cent of

real GDP. EXPGAP has been calculated in a similar manner using real

primary expenditure of the general government. The movements in the

dependent and the explanatory variables are plotted in Figure 5.

Results: Before proceeding with the estimation, all the series

were tested for stationarity. While all the explanatory variable series

were found to be stationary, i.e., I (0), the dependent variable series,

i.e., primary surplus to GDP ratio was found to be non-stationary.

However, after controlling for the years 2006-07 and 2007-08 (which

were the years when the general government in India recorded primary

surpluses), the series became stationary. In view of this, a dummy

variable (d surplus) has been introduced in the model to control for

the impact of these years. In addition, allowance has been made in the

estimations for the response of primary balance to GDP ratio to be nonlinear

and vary with debt levels by introducing a square term of the debt

to GDP ratio as an additional explanatory variable.

The OLS estimation results of the fiscal policy response function

are presented in Table 6. The coefficients of all the explanatory variables were found to be significant at one per cent level. Positive coefficient

of D indicates that primary surplus increases (or primary deficit falls)

in India in response to rising debt ratios. This implies that the primary

balance in India responds in a stabilising manner to increases in debt.

Positive coefficient of GDPGAP implies that primary balance improves

when GDP is above the trend. The negative coefficient of EXPGAP,

on the other hand, indicates that primary balance deteriorates when

primary expenditure is above the trend. These findings are in line with

the a priori expectations.

Table 6: Estimation Results |

Explanatory Variables |

Estimated Coefficients |

Model 1 (Linear) |

Model 2 (Non-linear) |

Constant |

-10.59* |

-30.83* |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

Dt-1 |

0.11* |

0.71* |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

Dt-1 2 |

|

-0.004* |

|

|

(0.01) |

GDPGAP |

0.25* |

0.19* |

|

(0.00) |

(0.01) |

EXPGAP |

-0.22* |

-0.25* |

|

(0.00) |

(0.00) |

d surplus |

1.69* |

1.62* |

|

(0.01) |

(0.00) |

AR(1) |

|

-0.25 |

|

|

(0.18) |

Adjusted R2 |

0.81 |

0.88 |

DW |

2.05 |

2.24 |

p-value of LM statistics (1st lag) |

0.49 |

0.10 |

Note: 1) Figures in the parentheses represent respective P values.

2) * denotes significant at 1% level. |

In the non-linear equation approach (Model 2), the response of the

primary balance to debt is better represented in terms of a quadratic

function rather than a linear response function. The results suggest that

the primary balance function has an inverted ‘u’ shape, implying that

the adjustment parameter first rises and then falls.

Both the models exhibited no residual serial correlation at the first

lag included. The p-values of the Breusch-Godfrey LM-statistics (as

presented in Table 6) are insufficient to reject the null hypothesis of no

autocorrelation.

Section VI

Impact of Public Debt on Growth: Threshold Level of Debt

There is a general belief among the economists that slower growth

is associated with higher level of debt. Several economists argue that

growth slows down sharply when the government debt to GDP ratio

exceeds a certain threshold level. There is, however, no consensus

regarding the threshold level of debt, beyond which the growth suffers.

In addition, the threshold level may vary widely across advanced and

emerging market economies. In this section, an attempt has been made

to examine the link between government debt real economic growth

in India during the period 1981-82 to 2012-13. In India, the level of

government debt seems to have an inverse relation with the growth in

GDP at market prices (Figure 6).

Model Specification: Empirical studies have considered different

set of control variables to analyse the impact of public debt on economic

growth. Some of these control variables include: population, investment,

export, openness, fiscal balance and years of schooling. In this paper, the impact of public debt on growth has been assessed by estimating the

following equation:

yt - yt-1 = α Dt + β1 Dt2 + β2 (it - it-1) + β3 πt + β4 (Tt –Tt-1) + β5 GFDt +εt

where y is the real GDP; D is public debt to GDP ratio; D2 is the

square of public debt to GDP ratio13; i is real investment; π is inflation

rate; T is international trade in real terms; GFD is the ratio of gross

fiscal deficit to GDP.

Data: The dependent variable real GDP is measured by GDP at

constant market prices. Combined outstanding liabilities of the central

and state governments of India have been used as a measure of the level

of public debt. Gross domestic capital formation at constant prices has

been used as a proxy for real investment. Inflation rate is measured by

growth in WPI. International trade is measured as the sum of non-oil

exports and imports in rupee terms at constant prices. Gross fiscal deficit

pertains to the general government. All the data are obtained from the

Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy. Summary statistics of

the relevant variables are furnished in Table 7. The correlation matrix

given in Annex 2 indicates absence of any serious multicollinearity

problem in the selected set of explanatory variables. It has been observed

that there is no statistically significant contemporaneous correlation

between debt-GDP ratio and GFD-GDP ratio.

Results: Before estimation, all the variables have been tested for

their stationarity properties. Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) unit analysis are stationary or not. The results of the ADF test indicate that

the null hypothesis of unit root can be rejected for all the variables.

After ensuring that all the series are I (0), the equation is estimated by

OLS and the results are presented in Table 8.

Table 7: Summary Statistics |

Variable |

High |

Low |

Mean |

Standard

Deviation |

Real GDP Growth |

10.5 |

1.1 |

6.2 |

2.3 |

Public Debt to GDP |

83.3 |

48.9 |

68.8 |

8.3 |

Growth in Real Investment |

29.8 |

-16.5 |

8.4 |

9.3 |

Inflation rate |

13.7 |

3.3 |

6.8 |

2.6 |

Growth in international trade |

35.6 |

-0.4 |

18.7 |

9.1 |

Gross fiscal Deficit to GDP |

9.6 |

4.0 |

7.6 |

1.4 |

The coefficients of all the explanatory variables are significant and

on the expected lines. The positive sign of Dt indicates that accumulation

of public debt leads to higher growth in real GDP up to a certain level.

The negative sign of Dt2 shows that the association of public debt and

real GDP turns negative beyond a certain threshold. The growth in real

investment has the expected positive sign which is significant at 1 per

cent level. Trade openness, as expressed in terms of growth in non-oil

exports and imports, also has a significant positive impact on growth.

High inflation and high fiscal deficit, on the other hand, have adverse

impact on growth. The dummy variable (d97) which has been used to

control the impact of growth slowdown in 1997-98 was found to be

significant.

Based on the coefficients of Dt and Dt2, the threshold level of public

debt for India works out to be around 61 per cent of GDP.

Table 8: Estimation Results |

Explanatory Variables |

Estimated Coefficients |

P-Value |

Public Debt to GDP Ratio (Dt) |

0.32* |

0.00 |

Square of Public Debt to GDP ratio (Dt2) |

-0.003* |

0.00 |

Growth in Real Investment (it – it-1) |

0.14* |

0.00 |

Inflation rate (πt) |

-0.36* |

0.01 |

Growth in international trade (Tt –Tt-1) |

0.08** |

0.03 |

Gross fiscal Deficit to GDP (GFDt) |

-0.46** |

0.04 |

Dummy Variable (d97) |

-4.24* |

0.01 |

Adjusted R2 |

0.57 |

|

DW Statistics |

2.13 |

|

LM statistics (1st lag) |

|

0.53 |

Note: * and ** denote significant at 1% and 5% level, respectively. |

These econometric findings are broadly in line with the results

on threshold level of debt of Mohanty (2013) and debt simulation

forecasts of Topalova and Nyberg (2010). While Mohanty has placed the threshold level of debt for India at 60 per cent of GDP, Topalova and

Nyberg have estimated the general government debt target/ceiling of at

most 60-65 per cent of GDP to signal commitment to fiscal discipline.

The debt simulation exercises undertaken by this IMF study are based

on the premise that the interest rate-growth differential would remain

favourable and contribute, on average, about 3 percentage points

reduction in the debt to GDP ratio per annum. It may be pertinent to

note that the Thirteenth Finance Commission (FC-XIII) had set a target

of 68 per cent of GDP for the combined debt of centre and states to be

attained by 2014-15.

Section VII

Conclusion

In this study, the sustainability of public debt in India at the general

government level was assessed through indicator-based analysis as well

as empirical exercises.

The empirical analysis carried out in this paper focused on

estimation of inter-temporal budget constraint and fiscal policy

response function to assess the sustainability of the present fiscal policy

in India. The estimation results reveal that there is a co-integrating

relationship between general government expenditure and revenue in

India, which satisfies the inter-temporal budget constraint. Moreover,

the estimated fiscal policy response function reveals that the primary

fiscal balance in India responds in a stabilising manner to the increase

in debt. Thus, both the results indicate that the current fiscal policies in

India are sustainable in the long run. However, it would be interesting

to take up a more comprehensive sustainability analysis covering

broader aspects, viz., costs of high public debt levels with respect to,

inter alia, crowding out of private investment, distortions on account of

large sectoral interventions like National Food Security Act, Mahatma

Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, etc, as areas of

further research.

The paper has also examined empirically the impact of public debt

on growth in the Indian context. The results of the empirical exercise

revealed that there is a statistically significant non-linear relationship

between public debt and growth, implying a negative impact of public debt on economic growth at higher levels. The threshold level of

general government debt-GDP ratio for India has turned out to be 61

per cent, i.e., the level beyond which an inverse relationship is observed

between debt and growth. This threshold level is lower than the actual

level of debt at 66.0 per cent in end March 2013. There are other risks

linked to volatility in international financial markets, and the narrowing

down of the interest rate-growth differential domestically. In these

circumstances, it would be desirable to strengthen the process of fiscal

consolidation both at the level of centre and states in the medium-term

so that borrowing is used only to meet capital expenditure which would

aid future growth. In addition, a turnaround in primary balance position

from deficit to surplus in the medium-term would be critical. It would

be important in the context of inter-temporal budget constraint faced

by the government and the need to provide for fiscal space to meet

challenges in an uncertain domestic and global environment.

References

Adams, Charles, Benno Ferrarini, and Donghyun Park. 2010. “Fiscal

Sustainability in Developing Asia”. ADB Economics Working Paper

Series No. 205, June 2010.

Aschauer, David Alan. 1988. “Is Public Expenditure Productive?”.

Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 23 (1989).

Aschauer, David Alan. 1989. “Does Public Capital Crowd Out Private

Capital?”. Journal of Monetray Economics, Vol. 24 (1989).

Baum, Anja Westphal, Cristina Checherita and Rother, Philipp. 2012.

“Debt and Growth: New Evidence for the Euro Area”. 14th Public

Finance Workshop, Banca DÍtalia, 29-31 March 2012.

Blanchard, Olivier J., Jean-Claude Chouraqui, Robert P. Hagemann and

Nicola Sartor. 1990. “The Sustainability of Fiscal Policy: New Answers

to an Old Question”. OECD Economic Studies, No. 15 (Autumn).

Boamah, D., and W. Moore. 2009. “External Debt and Growth in the

Caribbean”. Money Affairs, Jul–Dec.

Bohn, Henning. 1995. “The Sustainability of Budget Deficits in

a Stochastic Economy”. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking,

Vol. 27, No.1.

Bohn, Henning. 1998. “The Behavior of U.S. Public Debt and Deficits”.

Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 113 (August).

Bohn, Henning. 2008, “The Sustainability of Fiscal Policy in the United

States”. In: R. Neck and J. Sturm, “Sustainability of Public Debt”, MIT

Press.

Buiter, W. H. and U. Patel. 1992. “Debt, Deficits and Inflation: An

Application to Public Finances in India”. Journal of Public Economics,

Vol. 47, No.2.

Buiter, W. H. and U. Patel. 1995. Public Economics in India. Oxford

University Press, chapter Solvency and Fiscal Correction in India: An

Analytical Discussion.

Buiter, W. H. and U. Patel. 2010. “Fiscal Rules In India: Are They

Effective?”. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper

No. 15934, April 2010.

Cashin, Paul and Nilss Olekalns. 2000. “An Examination of the

Sustainability of Indian Fiscal Policy”. University of Melbourne

Department of Economics Working Papers No. 748.

Cecchetti, Stephen G., M. S. Mohanty and Fabrizio Zampolli. 2011.

“The Real Effects of Debt”. Monetary and Economic Department, BIS

Working Papers No 352, September 2011.

Chalk, Nigel and Richard Hemming. 2000. “Assessing Fiscal

Sustainability in Theory and Practice”. IMF Working Paper No.

WP/00/81.

Chang, T. and G. Chiang. 2009. “The Behavior of OECD Public Debt:

A Panel Smooth Transition Regression Approach”. The Empirical

Economics Letters 8 (1).

Checherita, C. and P. Rother. 2010. “The Impact of High and Growing

Government Debt on Economic Growth - An Empirical Investigation

for the Euro Area”. ECB Working Paper No. 1237.

Cordella, Tito, Antonio Ricci Luca and Marta Ruiz-Arranz. 2005. “Debt

Overhang or Debt Irrelevance? Revisiting the Debt-Growth Link”. IMF

Working Paper, WP/05/223, December 2005.

Cournède, Boris. 2010. “Gauging The Impact of Higher Capital and

Oil Costs on Potential Output”. Economics Department Working

Papers Eco/Wkp(2010)45, Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development.

Dholakia, R. H., T. T. Ram Mohan and Navendu Karan. 2004. “Fiscal

Sustainability of Debt of States”. Report submitted to the Twelfth

Finance Commission, New Delhi.

Domar, Evsey D. 1944. “The Burden of the Debt and the National

Income”. American Economic Review, Vol. 34, No.4.

Easterly, William R. 2001. “Growth Implosions and Debt Explosions:

Do Growth Slowdowns Cause Public Debt Crises?”. Contributions to

Macroeconomics, Vol. 1, No.1.

Égert, Balázs. 2012. “Public Debt, Economic Growth and Nonlinear

Effects: Myth or Reality?”. 14th Public Finance Workshop, Banca

DÍtalia, 29-31 March 2012.

Elmeskov, Jørgen and Douglas Sutherland. 2012. “Post-Crisis

Debt Overhang: Growth Implications Across Countries”. Second

International Research Conference on “Monetary Policy, Sovereign

Debt and Financial Stability: The New Trilemma”, 1-2 February, 2012,

Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, India.

Engle, Robert F. and C. W. J. Granger. 1987. “Co-Integration and Error

Correction: Representation, Estimation, and Testing”. Econometrica,

Vol. 55, No.2.

Gerson, Philip and David Nellor. 1997. “Philippine Fiscal Policy:

Sustainability, Growth, and Savings” in Macroeconomic Issues Facing

ASEAN Countries, edited by John Hicklin, David Robinson and Anoop

Singh (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Giovannini, Alberto and Martha de Melo. 1993. “Government Revenue

from Financial Repression.” American Economic Review, Vol. 83, No.4.

Goyal, R., J.K. Khundrakpam and Partha Ray. 2004. “Is India’s Public

Finance Unsustainable? Or, are the Claims Exaggerated?” Journal of

Policy Modeling, Vol. 26 (2004).

Greenidge, Kevin, Roland Craigwell, Chrystol Thomas and Lisa

Drakes. 2012. “Threshold Effects of Sovereign Debt: Evidence from

the Caribbean”. IMF Working Paper No. WP/12/157.

Hakkio, Craig S. and Mark Rush. 1991. “Cointegration: How short

is the long-run?”. Journal of International Money and Finance,

Vol. 10, No.4.

Hall, G. J. and T. J. Sargent. 2011. “Interest Rate Risk and Other

Determinants of Post-WW II U.S. Government Debt/GDP Dynamics”.

American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 3, No.3.

Herndon, Thomas, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin. 2013. “Does High

Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of

Reinhart and Rogoff”. Political Economy Research Institute, Working

Paper Series, Number 322.

Jha, R. 1999. Fifty Years of Development Economics. Himalaya

Publishing Company, chapter Some Rudimentary Macroeconomics of

the Budgetary Deficit and Debt.

Jha, R. and A. Sharma. 2004. “Structural Breaks, Unit Roots and

Cointegration: A Further Test of the Sustainability of the Indian Fiscal

Deficit”. Public Finance Review, Vol. 32, No.2.

Kumar, Manmohan S. and Jaejoon Woo. 2012. “Public Debt and

Growth”. 14th Public Finance Workshop, Banca DÍtalia, 29-31 March,

2012.

Legrenzi, G. and C. Milas. 2011. “Debt Sustainability and Financial

Crises: Evidence from the GIIPS”. The Rimini Centre for Economic

Analysis, WP 11-42.

Mohanty, M. 2013. “Public Debt Management and Macroeconomic

Stability”. Paper presented at the 2nd meeting of SAARC Public Debt

Managers’ Forum at Jaipur, India, during December 6-7, 2013.

Pattillo, C., H. Poirson and L. Ricci. 2002. “External Debt and Growth”,

IMF Working Paper 02/69.

Rangarajan, C and D. K. Srivastava. 2003. “Dynamics of Debt

Accumulation in India: Impact of Primary Deficit, Growth and Interest

Rate” . Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 38, No.46, November.

Rangarajan, C. and D. K. Srivastava. 2005, “Fiscal Deficits and

Government Debt in India: Implications for Growth and Stabilisation”,

NIPFP, Working Paper No. 35.

Reinhart, C. and K. Rogoff. 2010. “Growth in a Time of Debt”. American

Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, Vol. 100, No.2.

Reinhart Carmen M. and M. Belen Sbrancia. 2011. “The Liquidation of

Government Debt”. NBER Working Paper No. 16893.

Seshan, A. 1987. “The Burden of Domestic Public Debt in India”.

Reserve Bank of India, Occasional Papers, Vol. 8, No.1.

Singh, Charan. 1999. “Domestic Debt and Economic Growth in India”.

Economic and Political Weekly, No. 23, June 5, 1999.

Tiwari, Aviral Kumar. 2012. “Debt Sustainability in India: Empirical

Evidence from Estimating Time Varying Parameters”. Economics

Bulletin, 2012, Vol. 32, No.2.

Topalova, Petia and Dan Nyberg. 2010. “What level of Public Debt

Could India Target?”. IMF Working Paper, WP/10/7, January.

Tronzano, Marco. 2012. “Multicointegration and Fiscal Sustainability

in India: Evidence from Standard and Regime Shifts Models”.

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_

name=ICEEE5&paper_id=27.

Annex 1

Table A.1: Liabilities Position of the Centre and States

(Amount outstanding at the end of March) |

(Per cent of GDP) |

|

Components |

1990-91 |

2000-01 |

2004-05 |

2010-11 |

2011-12

RE |

2012-13

BE |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

I. |

Centre (1+2) |

62.7 |

53.9 |

61.5 |

50.5 |

49.8 |

49.5 |

|

1 Internal liabilities (A+B) |

56.4 |

50.8 |

59.6 |

48.5 |

47.9 |

47.7 |

|

A) Internal debt (i+ii) |

30.7 |

37.1 |

39.4 |

34.2 |

35.7 |

36.8 |

|

i) Market loans & bonds |

27.8 |

35.0 |

37.2 |

30.8 |

31.4 |

32.6 |

|

ii) Ways & means from the RBI |

2.9 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

|

a. Treasury bills |

1.6 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

3.1 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

|

b. Securities issued to International Financial Institutions |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

|

B) Other liabilities of which |

25.7 |

13.8 |

20.3 |

14.3 |

12.2 |

10.9 |

|

i) Small savings |

10.0 |

0.3 |

10.2 |

7.3 |

6.3 |

5.5 |

|

ii) Provident funds |

2.3 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

|

2 External debt |

6.3 |

3.0 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

II. |

States |

10.9 |

16.4 |

26.3 |

21.6 |

20.6 |

20.3 |

|

1. Market loans & bonds |

3.1 |

4.0 |

7.5 |

7.9 |

8.4 |

9.1 |

|

2. Ways & means from the RBI |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

3. Provident funds etc. |

3.4 |

4.3 |

4.0 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

2.7 |

|

4. Loans from banks & other institutions |

0.5 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

5. Special securities issued to NSSF |

0.0 |

2.6 |

8.7 |

6.3 |

5.4 |

4.8 |

|

6. Reserve funds and deposits & advances |

3.7 |

3.8 |

4.0 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

III. |

Total |

68.9 |

73.7 |

82.1 |

65.5 |

65.5 |

66.0 |

Notes: Total debt of centre and states may not add up due to adjustments on account of intergovernmental

transactions.

Source: Indian Public Finance Statistics, Government of India and Handbook of Statistics on

the Indian economy, RBI. |

Table A.2: Ownership Pattern of Central and State Government Securities |

(Per cent of Total Securities) |

Category of Holders |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

1. Reserve Bank of India (own account) |

6.6 |

7.1 |

8.9 |

8.6 |

10.4 |

2. Scheduled commercial banks |

51.0 |

50.4 |

52.0 |

51.4 |

53.8 |

3. Primary Dealers |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

2.8 |

4. Insurance Companies |

19.7 |

17.6 |

18.3 |

20.6 |

20.3 |

5. Financial Institutions |

1.0 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

6. Mutual Funds |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

7. Provident Funds |

4.0 |

4.0 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

8.Others |

17.1 |

18.9 |

14.2 |

12.4 |

7.3 |

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, RBI |

Table A.3: Short Term Debt of the General Government |

Year |

Amount (` billion) |

Per cent of Public Debt |

Per cent of GDP |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2007-08 |

1345 |

5.2 |

2.7 |

2008-09 |

2604 |

8.6 |

4.6 |

2009-10 |

3178 |

8.9 |

4.9 |

2010-11 |

2796 |

6.9 |

3.6 |

2011-12 |

4330 |

9.1 |

4.8 |

Source: Status Paper on Government Debt, GoI |

Table A.4: Floating Rate Debt of the Central Government |

Year |

Internal Floating Debt |

External Floating Debt |

Total Floating Debt |

Per cent

of Public

Debt |

Per cent

of GDP |

Per cent

of Public

Debt |

Per cent

of GDP |

Per cent

of Public

Debt |

Per cent

of GDP |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2001-02 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

3.7 |

1.7 |

3.9 |

1.9 |

2005-06 |

2.3 |

1.0 |

1.8 |

0.8 |

4.1 |

1.7 |

2009-10 |

1.6 |

0.6 |

2.1 |

0.8 |

3.7 |

1.5 |

2011-12 |

1.6 |

0.6 |

2.4 |

0.9 |

3.9 |

1.6 |

2012-13 RE |

1.2 |

0.5 |

2.3 |

0.9 |

3.5 |

1.4 |

Source: Status Paper on Government Debt, GoI |

Annex 2

Correlation Matrix for Debt Threshold Equation |

Variables |

Public

Debt to

GDP |

Growth

in Real

Investment |

Inflation

Rate |

Growth in

International

Trade |

Gross

Fiscal

Deficit to

GDP |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Public Debt to GDP |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

Growth in Real Investment |

0.33 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

(0.07) |

|

|

|

|

Inflation Rate |

-0.02 |

-0.18 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

(0.92) |

(0.31) |

|

|

|

Growth in International Trade |

0.26 |

0.06 |

0.49* |

1.00 |

|

|

(0.15) |

(0.73) |

(0.00) |

|

|

Gross Fiscal Deficit to GDP |

0.24 |

-0.06 |

-0.10 |

-0.14 |

1.00 |

|

(0.18) |

(0.75) |

(0.59) |

(0.46) |

|

Note: 1. Figures in the parentheses indicate respective p values.

2. * indicates significant at 1 per cent level. |

|