Terms of Reference of the Committee • To review the existing state of mortgage backed securitisation in India, including the regulations in place, and to make specific recommendations on suitably aligning the same with international norms; • To analyse the prevalent structures for mortgage backed securitisation transactions in India including legal, tax, valuation, and accounting related issues, and suggest modification to address requirements of both originators and investors; • To identify critical steps required for standardisation of mortgage backed securitisation practices such as conforming mortgages, mortgage documentation standards, digital registry for ease of due diligence and verification by investors; • To assess the role of various counterparties, including the servicers, trustees, rating agencies, etc in the securitisation process and suggest measures required, if any to address the key risk viz structural, fiduciary, and servicer risk; • To recommend specific measures for facilitating secondary market trading in mortgage securitisation instruments, such as broadening investor base, and strengthening market infrastructure ; • To analyse inter-linkages between securitisation and other related financial market segment. Instruments and recommend necessary policy interventions to leverage these inter-linkages; and • To identify any other issue germane to the subject matter and make recommendations thereon Committee Members Dr Harsh Vardhan, Senior Advisor, Bain & Co

Chair Shri Chandan Sinha, Additional Director, CAFRAL

Member Ms Bindu Ananth, Chair & Trustee, Dvara Trust

Member Ms Pranjul Bhandari, Chief Economist India, HSBC

Member Shri Sanjaya Gupta, MD & CEO, PNB Housing Finance Ltd

Member Shri Naresh Takkar*, Former MD & CEO, ICRA

Member The Committee held 7 meetings between 12 June and 30 August, 2019 (*Shri Takkar did not attend any meetings after the second meeting of the Committee)

Acknowledgements The Committee expresses its gratitude to the RBI Governor Shanktikanta Das for his initiative to focus on the development of securitisation for housing finance, which is a key element of the overall development of the financial sector in India. It would also like to thank N S Vishwanathan, Deputy Governor and Lily Vadera, Executive Director for sharing their views and providing support to the Committee. T Rabi Shankar, SP Mohanty, Manoj Kumar, and Ankush Andhare from the RBI provided inputs on important regulatory issues. Vaibhav Chaturvedi, Sooraj Menon, and Arun Babu from the RBI provided all the logistical support as also access to important documents and people. The Committee expresses its heartfelt gratitude to the RBI team. The committee benefitted from the perspectives and insights of several individuals that are experienced and deeply knowledgeable about securitisation globally and in India. They made presentations or engaged in discussions with the Committee, which helped it develop a comprehensive view of the issues in securitisation. The Committee thanks these individuals and organisations they represent: -

Shabnum Kajiji and Nihas Bashir of Wadia Ghandy -

Bobby Parikh and Anand Laxmeswar of Bobby Parikh Associates -

Kshama Fenandes, Remika Agrawal, Shakeel Ahmed, Anshul Gupta of Northern Arc Capital -

Vinod Kothari, Kamal Baheti, Abhirup Ghosh of Indian Securitisation Forum -

VS Rangan of HDFC -

Mahesh Misra, Sovon Mandal, Shrikant Srivastava of Indian Mortgage Guarantee Corporation -

Loic Chiquier, Simon Christopher Wally, Mehnaz Safavian, of the World Bank and Poorna Bhattacharjee of the IFC -

Christine Engstrom of the Asian Development Bank -

James Pedly of Clifford Chance -

Rahul Goswami of ICICI Prudential Mutual Fund & R Sivakumar of Axis Mutual Fund -

Bhadresh Kulhalli of HDFC Standard Life & Vidya Iyer of ICICI Prudential Life Insurance -

K Chakravarty of the National Housing Bank The Committee also thanks several others who contributed the committee’s thinking through conversations, sharing notes and white papers, providing data, etc with individual members of the committee. They are: -

Pankaj Jain of the Ministry of Finance -

Raj Vikas Verma, former CMD of National Housing Bank -

Vibhor Mittal and Abhijeet Ajinkya of ICRA -

M B Mahesh & Dipanjan Ghosh of Kotak Institutional Equities -

Seema Iyer & Jian Johnson of ICICI Bank -

Srivatsan Bhaskaran, PH Ravikumar, Sandeep Menon of Vaastu Home Finance -

Raman Uberoi & Krishnan Sitharaman of CRISIL -

Deep Nagpal, Kyson Ho, Madhur Malviya, Chetan Joshi of HSBC -

Aditi Bagri & Bijal Ajinkya of Khaitan & Co -

Charanjit Attra of E&Y -

Nipa Sheth, Hani Jalan, Chetan Rao, Parag Kothari of the Trust Group -

Anjali Sharma, Bhargavi Zaveri of Finance Research Group at IGIDR -

Malavika Raghavan, Nandini Vijayaraghavan, Madhu Srinivasan of Dvara Research -

Kapish Jain and Krishan Gopal of PNB Housing Finance Limited -

Akhilesh Tilotia, Jayesh T

Chapter 1: Executive Summary & List of Recommendations 1. Housing development and democratised home ownership are important economic and social policy objectives in India. Economic development and rising per capita income has created a new aspirational India. Owning a home is an essential part of Indian aspirations. Housing is also one of the key priority areas for governments, both at the Centre and the States, since the Independence and will continue to remain so. Housing development is a key driver of broader economic and community development, employment creation, asset creation, and wealth accumulation. 2. Despite policy focus and sustained government efforts, India still suffers from a housing shortage that could increase with a rising population. Analyst and Government of India estimates suggest that India will need anywhere between 8 crore to 10 crore additional housing units by 2022; the costs of building these additional units could be from ₹100 lakh crore to ₹115 lakh crore. To meet the ambitious target of ‘Housing for All’ by 2022, enhanced efforts will be needed on issues that relate to housing, as also those that relate to finance for housing. 3. India has predominantly private ownership of housing (i.e. the state does not provide it). Buying a house is the largest expenditure for most homeowners and hence needs access to credit. Increasing home ownership will require wider and easier access to credit, i.e. loans for home buying. Presently, in India, housing finance companies (HFCs) and commercial banks are the main providers of home loans. For these providers to be able to meet the growing demand for home loans, they must have funding (or liability) sources that keep up with the growth of loans. Banks’ main funding source is deposits (time and demand) that they use to mobilise household savings. HFCs, on the other hand, are wholesale funded in that they rely primarily on banks and, to some extent, on debt capital markets for sourcing liabilities. Refinance provided by the National Housing Bank (NHB) is also a source of funding, especially for smaller HFCs. 4. The home loan business of HFCs is highly concentrated with the top five HFCs accounting for over 85 per cent of the loans. These large HFCs have access to bond markets in addition to banks’ borrowing and refinance as their source of funding. However, of the hundred or so HFCs, those beyond the top ten are almost entirely reliant on banks and NHB refinance for funding. These smaller HFCs play a critical role in providing home loans to economically weaker sections in dispersed geographies. In order for the home loan business to grow, lenders, especially the small and medium sized HFCs, will need access to a diverse set of capital pools to source funding. 5. Home loans have a unique characteristic that creates challenges for the lenders. They have long maturity that can go up to 30 years. For the lender, such long maturity assets need matching maturity liabilities to avoid the asset liability mismatch problem. Most of the funding sources of banks and HFCs have maturity of up to five years. Growth of home loans, thus, presents a growing, structural asset liability management (ALM) challenge for the lenders. In addition to being a source of funding, securitisation could be an instrument that allows lenders to address, at least partially, the ALM challenge. 6. Securitisation involves pooling of loans and selling them to a special purpose vehicle (SPV) which then issues securities called pass-through certificates (PTCs) backed by the loan pool. For lenders of home loans, securitisation would involve pooling of home loans. Securitisation is a mechanism to convert illiquid loans on the lenders’ balance sheet into tradeable securities. Creation of tradeable securities allows wider pools of capital, especially those that have longer maturity liabilities (e.g. insurance and pension funds) to invest in housing loans. A well-developed securitisation market can emerge as a reliable complement to other sources of funding for home loan lenders. Experience from countries with developed securitisation markets shows that securitisation tends to be countercyclical; volumes go up when liquidity in the overall capital markets is low and vice versa. A well-developed securitisation market can thus reduce volatility in funding for lenders. 7. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) provides regulatory oversight over securitisation transactions in India. It issued guidelines in 2006 and 2012 that together define the regulatory framework for securitisation. These guidelines cover two types of transactions within the ambit of securitisation – direct assignment (DA) and pass through certificates (PTC). The common feature of these two types of transactions is that they both involve pooling of loans and selling them to a counterparty, therefore transferring credit risk. However, in case of DA, no intermediary (ie an SPV) is involved nor are any securities issued. Thus, DA is more in the nature of a ‘loan sale’ and will not be considered as securitisation as per the most widely accepted definition. 8. Securitisation volumes in India have grown significantly since 2006 when RBI issued its first securitisation guidelines. The total volume of securitisation has grown from ₹23,545 crore in 2006 to ₹266,264 crore in 2019. The growth, especially in the last decade, has been dominated by DA transactions, and PTC share of the total volume in 2019 was just about a quarter. The skew towards DA is even stronger in home loans where less than 10 per cent of the home loan securitisation transactions (~two per cent of all securitisation transactions) by volume are PTC. 9. Characteristics of a DA model dominated securitisation is that most transactions are customised, bilateral transactions where the originator and the investor engage in extensive discussions and diligence on the loan pools that are securitised. Such customised, bilateral transactions rule out the possibility of ‘arm’s length’ capital pools (eg mutual funds, insurance, and pension funds) from participating. Further, information about the transactions (valuation, pool performance, prepayment levels, etc) remains in the private domain and is not available to market participants. For wider pools of capital to participate in securitisation, the transaction has to be efficient and transparent. 10. Review of the status of securitisation for housing finance reveals some clear priorities for its development - (1) Banks represent a very large capital pool, which will remain very important for housing finance securitisation. However, it is important for the overall development of the securitisation market to balance banks’ participation between the direct assignment (DA) model and the pass-through certificate (PTC) model (2) banks‘ pursuit of securitisation is currently motivated primarily by the need to acquire priority sector compliant loan pools. For broader development of securitisation, capital pools must have economic incentives beyond just regulatory compliance (eg the priority sector lending obligations) and should invest in housing loan pools of all types (3) investor base for housing finance securitisation must be broadened, especially to include pools with longer maturity funds such as pension and insurance. 11. Enhancing efficiency of securitisation transaction requires elimination or minimising of transaction costs. These costs arise from several sources including legal and regulatory requirements, activities and documentation, structure of the transaction itself, uncertainty in taxation, accounting standards, etc. In order to reduce the transaction costs, all these issues have to be carefully assessed making sure that any steps taken to reduce the transaction costs do not increase risks. 12. Lack of transparency in any transaction is an outcome of lack of standardisation and inadequate disclosures. As discussed earlier, securitisation in India hitherto has been dominated by customised, bilateral DA transactions that have very little standardisation and almost no disclosures. Lack of standardisation is also prevalent in the underlying home loan business where the documentation and the data related to the loans vary greatly across lenders. Development and scaling up of securitisation will depend on standardisation of the process, the documents, the data, and the disclosures related to the transaction. 13. Recent decision of moving the regulatory functions for HFCs from the NHB to RBI would, over the course of time, align and converge regulatory framework for banks and HFCs related to the home loan business. It will also provide an opportunity to take significant steps towards standardisation of the securitisation process across banks and HFCs. 14. The perspective of enhancing efficiency and transparency of securitisation transaction guided the Committee’s thinking. It looked at the entire life cycle of the transaction and all the parties involved in it. The recommendations are divided into three buckets - those related to the originator of the transaction, the investor in the transaction, and some enablers that do not directly impact securitisation but can help it develop. The list of the recommendations is below: I. Originator-related Recommendations 1. Stamp duty: (a) The Central government can exempt a mortgage-backed securitisation transaction from Stamp Duty in the same manner that assignment stamp duty towards asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) and stamp duty for factoring transactions (which also entail assignment of receivables) have been exempt; or (b) Stamp duty on assignment of mortgage pools in a securitisation should be standardised and capped at a reasonable level across all states. 2. Registration requirements: (a) The Central Government can exempt the transfer of mortgage debt from compulsory registration under the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 and the Registration Act, 1908 based on the rationale that the mortgage loans are essentially movable assets unlike the underlying security and hence transferring them should not require registration as the underlying mortgages are, wherever mandatorily required, anyway registered. (b) In order to ensure that public records are maintained for such exempt transactions, a requirement to register such transactions through a digital registry such as Central Registry of Securitisation Asset Reconstruction and Security Interest of India (CERSAI) with a nominal registration fee can be considered. 3. Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) benefit for enforcing security interest should be extended, through a notification, to securitisation trustee in a mortgage-backed securitisation transaction and its agents (for collection). 4. Regulatory treatment for DA and PTC should be distinct with separate guidelines prescribed for DA and PTC transactions. Guidelines on securitisation should apply only to PTC transaction and not DA transactions, which should not be treated as securitisation. 5. Regulatory treatment should be distinct for mortgage-backed securitisation (MBS) and other asset-backed securitisation. RBI should issue clear and separate guidelines for mortgage-backed securitisation. 6. Assigned assets should be eligible for securitisation by the assignee as long as the underlying mortgage pool satisfies all the other relevant regulatory conditions for securitisation. 7. For mortgage-backed securitisation, the minimum holding period should be reduced to six months/six-monthly instalments (permanently). 8. For mortgage-backed securitisation, the minimum retention requirement (MRR) should be reduced to five per cent or equity (non-investment grade) tranches, whichever is higher. Any first loss credit enhancement provided by the originator will be included in the MRR. If the equity tranche and credit enhancement together are less than five per cent, then the difference must be held pari passu in other tranches. 9. Home loans pricing should be linked to an external, objectively observable benchmark (such as the repo rate). Lenders should be mandated to publicly disclose the external benchmark that is used to price floating rate loans and the periodicity of repricing. 10. For mortgage-backed securitisation, first reset in credit enhancement should be allowed at 25 per cent of repayment of the underlying pool and subsequent reset at every 10 per cent further repayment. 11. It would be prudent to implement Basel III guidelines for securitisation exposures along with the rest of the Basel III package as and when it is implemented in India, after understanding the implications of the revised risk weight prescriptions that continue to rely on external ratings, through an impact analysis. 12. RBI should align its securitisation guidelines to the standards set by IndAS. Specifically, the guidelines related to the accounting for upfront profits in securitisation transactions should be aligned. 13. RBI should continue to use its own standards of true sale to determine de-recognition for the purposes of computing capital requirement for the originator, even if under IndAS the assets are not de-recognised. 14. The post securitisation risk capital requirements for the originators should be capped at a level that it would have to maintain if the underlying pool had not been securitised. 15. Section 115JB of the Income Tax Act, 1961 should incorporate a carve-out in respect of EIS recognised as income as per IndAS; instead, such income should be deemed to be recognised in the books over a period of time until the transaction is complete and the exact extent of EIS is known. 16. The tax administration may issue a circular clarifying that originators, as hitherto, may be allowed to offer EIS to tax on the basis of the revenue recognition schedule provided. 17. The tax administration may also issue a circular clarifying that no part of EIS is to be treated as servicing fees and hence attract GST. II. Investor related recommendations 18. Banks should be allowed to classify mortgage-backed securities with the original maturity of over a predefined threshold (eg five years) or as per the declared intent at the time of acquiring the securities, under the Held to Maturity (HTM) category. 19. A separate and specific limit of five per cent should be allowed for MBS in the provident fund, pension fund and insurance investment guidelines. EPFO, PFRDA, and IRDAI should issue notifications for these new limits. 20. Regulatory directions on Repurchase Transactions (Repo) should include PTCs issued through a mortgage-backed securitisation transaction as eligible securities. 21. Credit Default Swap (CDS) guidelines should include PTCs issued in a mortgage-backed securitisation transaction as eligible reference obligation. 22. Income received by the securitisation trustee should continue to be exempt from income-tax. 23. Investments in the PTCs should be regarded as having been made in debt instruments and tax treatment on receipts from PTCs should be consistent with nature of receipts; ie interest should be taxed as per the applicable provisions of the Income Tax Act, 1961 and principal repayments should remain untaxed (since there is no income element involved). 24. PTCs issued in mortgage-backed securitisation should be on par with corporate bonds. As with such bonds, interest payments made to resident investors in listed PTC should not be liable for tax withholding. Interest payments to non-resident investors in PTC should be aligned with the tax withholding rate that applies to interest income earned by non-resident holders of units of Real Estate Investment Trusts or Infrastructure Investment Trusts (which is five per cent currently). 25. PTCs issued in mortgage-backed securitisation should be mandatorily listed if the securitisation pool is larger than ₹500 crore. 26. Financial sectors regulators should prescribe standardised methods for valuation of PTCs of mortgage-backed securitisation that are based only on the characteristics and the performance of the pool and are not influenced by the financial status of the originator. III. Enabler Recommendations 27. Any law for resolving bankruptcy of financial firms must ensure that the assets underlying a securitisation transaction, as well as any exposures in the form of credit enhancement, should be bankruptcy remote and not become a part of firms’ liquidation or resolution process under the law. 28. Standardisation: -

Loan documentation must be standardised for housing loans. Documents for the three alternative forms of underlying mortgages (equitable mortgage that is registered, equitable mortgage that is not registered, and registered (legal) mortgage) should be standardised and adopted by all lenders -

Housing loan related data and the format of capturing that data must be standardised so that aggregation of this data becomes easy for the purpose of creation of loan pools -

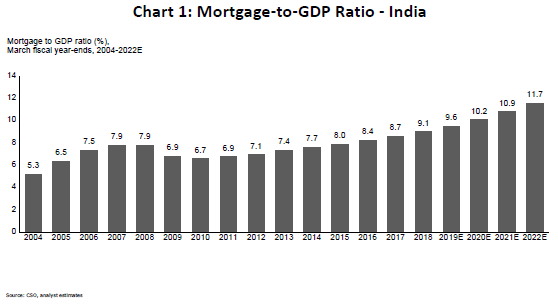

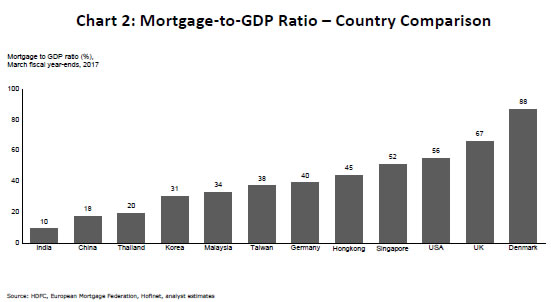

Minimum standards for loans qualifying to be securitised must be defined. Loans conforming to these standards would be eligible to be pooled for securitisation. 29. Loan servicing process should be standardised and be adapted by all mortgage lenders. A Master Servicing agreement describing the standardised servicing process should be developed and adhered to by all lenders. 30. NHB should undertake efforts to establish the loan origination standards (at least for the affordable housing loans) on a priority basis and set up the infrastructure for obtaining and disseminating pool performance data for all securitisation transactions. 31. An intermediary to promote housing finance securitisation with the primary functions of standard-setting and market making should be established by NHB. Chapter 2: Overview of Housing and Housing Finance I. Introduction Housing is a fundamental need of human existence. It is one of the key priority areas for governments, both at the Centre and the States, since the Independence and will continue to remain so. Housing development is a key driver of economic and community development, jobs, and wealth accumulation. A house is not merely a place to live and build a life; it is also one of the most significant assets for a family. An investment in a house roots a family to a location, giving them a significant stake in the economic and social development of the local area. The house can also be an appreciating asset and can create a wealth-effect allowing families to stretch themselves somewhat in times of need or increase in consumption. It is important to recognise that housing policies of the day can have a significant bearing on the trajectory of their prices and hence on the relative incentives and security coverage for various stakeholders like owners, lenders, builders, etc. The development of a housing and housing finance market entails the conversion of a physical unit of infrastructure into a bundle of economic rights and liabilities that are standardised. The standardisation of economic agreements and legal architecture can lead to the creation of a tradeable market in such rights and liabilities. The rights in a property can create significant economic value and allow various players like lenders, tenants, service providers, etc. to take economic interest in a property. Standardised loan agreements also allow pooling, sharing and diversification of risks by bringing together different types of borrowers in a portfolio. This reduces the costs of ownership and increases the purchasing ability, as lenders have comfort in financing home-equity owners. II. Current Status of Housing in India Like any other market, housing comprises many segments that have their unique characteristics and requirements. The various segments of housing, in the context of India, are commonly defined as ‘Economically Weaker Section’ (EWS), ‘Low Income Group’ (LIG) and ‘Middle Income Group (MIG) and above’ (MIG+). These segments are typically defined either with the income range of the principal home-owner or the loan value taken; the two variables tend to be correlated. The typical EWS, LIG and MIG+ segments have annual incomes of up to ₹three lakh, between ₹three lakh and ₹three lakh, and above ₹six lakh, respectively. The loan value cut-off in each segment is ₹10 lakh, between ₹10 lakh and ₹25 lakh, and above ₹25 lakh, respectively. This segmentation also provides a good sense of the typical profile of the borrower/homeowner in each category. RBI’s definition of a housing loan to qualify as priority sector lending is ‘Loans to individuals up to ₹35 lakh in metropolitan centres (with a population of 10 lakh and above) and loans up to ₹25 lakh in other (non-metro) centres for purchase/construction of a dwelling unit per family, provided the overall cost of the dwelling unit in the metropolitan centre and at other centres does not exceed ₹45 lakh and ₹30 lakh, respectively.’ The current housing finance market in terms of value and numbers of houses has two divergent segments in terms of value and numbers. The total value of housing finance is large in the high-value segment that has relatively low numbers of houses while the very large number of houses in the informal or low-value housing tend not to command large market value. The total value of housing in India is estimated to be ~₹150 lakh crore, which is far greater than the market capitalisation of equity markets. Housing continues to remain one of the largest investment avenues for the citizens of India. In spite of its large numbers, the current housing base does not meet housing needs of all citizens of India leaving many of them in either poor-quality housing, or in some cases, without housing altogether. The shortage of housing is material both in terms of number of houses and the value of housing as detailed in Table 1. The stock of housing in India requires significant upgrades especially as incomes rise with economic growth. Poor or non-justiciable legal and economic rights to the property can lead to shortage and poor quality of housing. | Table 1: Shortage of Housing Units in India | | | 2007 | 2012 | | Shortage and requirement (mn) | | | | EWS | 21.8 | 10.6 | | LIG | 2.9 | 7.4 | | MIG and above | 0.0 | 0.8 | | Total | 24.7 | 18.8 | | Value of units, LTV to be financed by HFCs, SCBs (Rs Lakh Cr) | | | | EWS | 10.9 | 5.3 | | LIG | 2.9 | 7.4 | | MIG and above | 0.2 | 4.1 | | Total | 14.0 | 16.8 | | Total (US$ tn) | 0.2 | 0.2 | | Construction costs (Rs Lakh Cr) | | | | EWS | 10.9 | 5.3 | | LIG | 2.2 | 5.6 | | MIG and above | 0.1 | 1.6 | | Total | 13.1 | 12.5 | | Total (US$ tn) | 0.2 | 0.2 | | Source: Planning Commission, Kotak Institutional Equities | Shortage of housing is pervasive across all states and all segments even as the intensity of the shortage may vary. It is noteworthy that the states that have higher per-capita incomes tend to have lower housing shortages. However, even such states have a significant unmet need for housing upgrades. Table 2 details the projected housing requirement across the various economic segments. As can be seen, the quantity of housing and the value of housing shortages are meaningfully different across all segments. Depending on the projection, the requirement can vary between ₹100 lakh crore and ₹115 lakh crore. | Table 2: Projected Housing Requirement by 2022 | | | Analyst estimate | Govt of India estimate | | Shortage and requirement (mn) | | | | EWS | 33.6 | 45.0 | | LIG | 44.0 | 50.0 | | MIG and above | 6.4 | 5.0 | | Total | 80.0 | 100.0 | | Value of units, LTV to be financed by HFCs, SCBs (Rs Lakh Cr) | | | | EWS | 25.2 | 33.8 | | LIG | 88.0 | 100.0 | | MIG and above | 51.2 | 40.0 | | Total | 164.4 | 173.8 | | Total (US$ tn) | 2.3 | 2.5 | | Construction costs (Rs Lakh Cr) | | | | EWS | 26.9 | 36.0 | | LIG | 55.0 | 62.5 | | MIG and above | 19.2 | 15.0 | | Total | 101.1 | 113.5 | | Total (US$ tn) | 1.4 | 1.6 | | Source: Planning Commission, analyst estimates | III. Penetration of Housing Finance Across Segments One of the key ownership methods for houses is through home loans (ie mortgages). Mortgages have become a popular means of facilitating the purchase of a house across all segments – even though the needs and product requirements vary significantly across the segments. India has a very low mortgage-to-GDP ratio compared to other countries. This ratio is expected to grow significantly over the next few years (charts below provide the details).

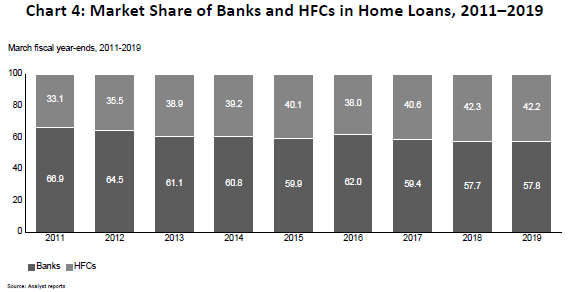

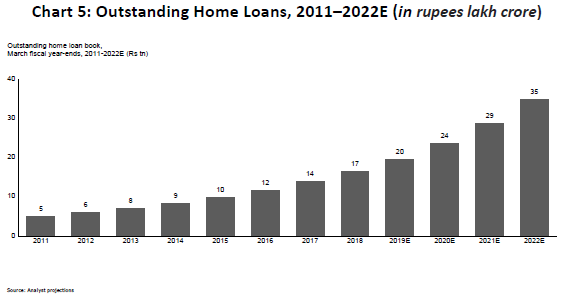

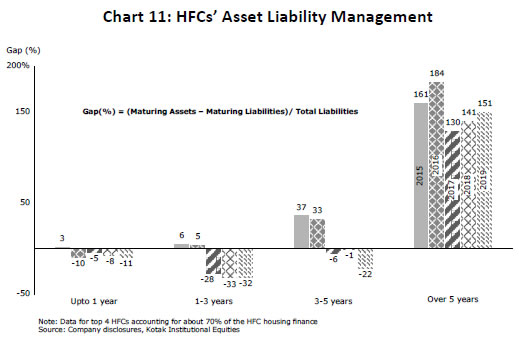

Table 3 provides estimates of mortgage financing in various housing market segments by 2022. These estimates suggest that the market is large in the MIG+ segment driven by the bigger ticket-sizes and similarly it is large in LIG due to the larger number of houses. These estimates also suggest that EWS category could continue to see low credit penetration even though the objective of the Governments at both Centre and States will be to address this market failure. The total incremental demand of ₹50 lakh crore to ₹60 lakh crore suggests significant growth considering the total outstanding home loan amount at the end of FY2019 was ₹20 lakh crore. By the end of FY2022, the total outstanding home loans are expected to reach ₹35 lakh crore, which is over 20 per cent compounded annual growth over the FY2019 number. Different segments also have different providers catering to the housing market; the real estate developers in one segment typically do not serve other segments. The geographical catchment area, even within a city, may be meaningfully different across the various segments. The income profile across segments also materially varies not just in terms of the income level but also the volatility or riskiness of the income. Given these differences, specialized providers have emerged to cater to the unique needs in the different segments. | Table 3: Estimates for Aggregate Demand for Housing (rupees in lakh crore) | | | Analyst estimate | Govt of India estimate | | Units required (mn) | | | | EWS | 36 | 45 | | LIG | 38 | 50 | | MIG and above | 5 | 5 | | Total | 79 | 100 | | Value of units (Rs Lkh Cr) | | | | EWS | 27 | 34 | | LIG | 56 | 75 | | MIG and above | 40 | 40 | | Total | 123 | 149 | | LTV (%) | | | | EWS | 40 | 40 | | LIG | 50 | 50 | | MIG and above | 65 | 65 | | Credit penetration (%) | | | | EWS | 40 | 40 | | LIG | 80 | 80 | | MIG and above | 85 | 85 | | Aggregate loan demand (Rs Lakh Cr) | | | | EWS | 4 | 5 | | LIG | 23 | 30 | | MIG and above | 22 | 22 | | Total | 49 | 58 | | Source: Kotak estimates | The penetration of housing finance differs across segments and each segment is served very differently by banks and HFCs. The housing finance market is relatively well-served in the MIG+ segment by commercial banks and some larger and more matured housing finance companies. As we move to the LIG and EWS, we find the proportion of loans given by HFCs, especially smaller HFCs, increases. Some of these loans are bought by banks from the HFCs to meet their priority sector lending obligation. However, in terms of disbursements, HFCs take the lead in the non-MIG+ segments. There is also a difference in the penetration of housing finance between urban and rural areas. While the finance penetration in rural areas has lagged behind, it is catching up. This trend suggests that rural areas could have a relatively greater share of future growth in housing finance. IV. Providers of Housing Finance: Banks, HFCs In India, home loans are provided mainly by commercial banks and housing finance companies. HFC as a model came into being in the early 1980s and were pioneers in home loans. Commercial banks entered this business in a significant way in early 2000’s. Rapid growth of housing loans in banks’ portfolio over the last two decades has resulted in these loans becoming a significant component of the overall loan portfolio of banks. By financial year 2019 total home loans outstanding in the banking system were ~₹11.5 lakh crore, representing around 58 per cent of the total home loans outstanding. HFCs, on the other hand, had outstanding home loans of ₹8.5 lakh crore, around 42 per cent of the total home loans.  Chart 4 shows the market share of home loans outstanding between banks and HFCs over the years. As can be seen, the HFCs have gained the market share. Banks also purchase housing loan portfolios from other intermediaries and so the stock of loans outstanding may not reflect the proportion of disbursements. Even though these numbers appear large and growing, as discussed above, India has a low mortgage-to-GDP ratio, compared even to peer developing countries. This reflects the low penetration of housing finance that can be attributed to several reasons; it also points to a very large opportunity for growth. Since HFCs address more over 40 per cent of the mortgage market, the recent liquidity challenge in non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) and HFCs may create a temporary blip in the secular growth story. V. Growth in Housing Finance Given the unmet demand for housing and low penetration of mortgages in India, the housing market, and the financing market associated with it, is expected to see secular growth over the next many years. According to analysts’ estimates, home loan outstanding is expected to increase from ~₹20 lakh crore in FY2019 to ₹35 lakh crore by FY2022. Chart 5 details the total projection of the mortgage market over the next few years.  In addition to rapid growth, another important change in the housing market over the next decade will be the impact of increased urbanisation. Chart 6 details the levels of urbanisation in India over the last many census years and the projections going forward. As Indian cities expand to take in more people, business will start to shift towards the current peri-urban areas. This shift has given rise to the affordable housing finance segment, with more than 100 institutions, comprising both banks and HFCs as of March 2018. In terms of volumes, HFCs in the affordable new housing segment had a total outstanding of ₹41,363 crore as of March 2019. This represents a 19 per cent year-on-year (YoY) growth compared to the previous year. However, it should be noted that growth in this segment has slowed down from an annualised YoY growth rate of 96 per cent in March 2016 to only 19 per cent in March 2019. In terms of composition, home loans comprised 62 per cent of the affordable housing portfolio, while LAP and construction finance comprised 20 per cent and 15 per cent, respectively. The NPA levels of the AH sector has been consistently higher than the overall NPA level of the HFCs. From a GNPA level of two per cent in March 2014, it reached a peak of five per cent as on December 2018. Some improvement can be seen since then, with the ratio dropping to 4.7 per cent as of March 2019. However, this improvement was largely supported by write offs and sale of NPAs by some HFCs. (All data in the paragraph above from Indian Mortgage Finance Marker report of ICRA, June 2019) VI. Funding Models of Banks and HFCs Home loans are important and attractive products for banks and HFCs for several reasons. They have grown steadily at over 17 per cent for the last decade. They are secured and since the value of the property generally tends to increase over time, the security cover for the home loans increases. Over economic cycles, home loans have had among the lowest non-performing asset (NPA) levels among all classes of loans. For banks, there is the added attractiveness of some (smaller ticket size) home loans qualifying as priority sector lending. Finally, given the lower risk weights on home loans (currently between 50 per cent and 75 per cent, depending on the size of the loan and the loan to value ratio), they deliver good return on equity (RoE) for the lender despite very competitive pricing. Balancing these attractive features, home loans also present some challenges for the lenders. The most important challenge is posed by the long maturity of these loans. Most home loans have maturity of 15 to 20 years at the time of origination. For younger borrowers, the maturity can go up to 25 or even 30 years. While prepayments are quite common, even after adjusting for prepayments, home loans have a maturity of 8 to 10 years making them the longest maturity assets for banks and HFCs. In addition to the long maturity, prepayments and balance transfers also create competitive pressure as well as a degree of uncertainty regarding maturity of home loans. The challenge posed by longer and somewhat unpredictable maturity of home loans is better understood in the context of the funding model of banks and HFCs. Primary source of funding for banks are deposits – time (term or fixed) deposits and demand deposits, which includes current and savings account, commonly referred to as CASA accounts. Of the total deposits in the Indian banking system presently, term deposits account for ~58 per cent, savings account deposits for ~33 per cent and current account deposits ~nine per cent. Savings accounts grew rapidly post demonetisation in 2016. If one looks at the data for the financial year 2016, the share of term, savings, and current deposits were 63 per cent, 28 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively. About 85 per cent of term deposits of banks have maturity of less than five years. Even if we assume ‘behavioural’ maturity of around 3 years for savings accounts (as most banks do for the purpose of their asset-liability management analysis), over 90 per cent of all deposits of banks have a maturity of less than five years. In fact, the weighted average maturity of banking system deposits works out to around 2.5 years. Unlike banks, HFCs are wholesale funded, i.e. they do not have access to public deposits. Table 4 provides details of the funding mix of HFCs as a group. It shows that about 40 per cent of funding for HFCs is from banks (including debentures issued to banks) and ~30 per cent is from debentures issued to non-banks (e.g. mutual funds). Thus, the main source of funding is bank borrowing. Only a handful of HFCs are permitted to raise public term deposits. However, the share of funding raised through public deposits for HFCs is below 10 per cent. This data is for all HFCs - there are over 100 registered HFCs. Of these, only the top ten or so have the ratings and market standing to have reliable and stable access to debt capital markets ie placing debentures with funds or individuals. Majority of smaller HFCs rely on bank borrowing as their only source of funding. They also have access to refinance facilities of the National Housing Bank. Bank lending to HFCs generally has a maturity of less than five years. Thus, for both banks and HFCs home loans present an asset liability mismatch problem – the maturity of assets (ie home loans) is much longer than that of liabilities. The challenge is much more acute for HFCs, especially those that are not among the top ten, where the only source of funding for them is banks and if for any reason this source dries up, they cannot grow their home loan books. | Table 4: Composition of Borrowings of all HFCs, 2016–2018 | | | Rs crore | Proportion | | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | | NHB borrowings | 26,440 | 36,347 | 39,259 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.2 | | Foreign borrowings | 9,398 | 14,135 | 15,291 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.6 | | Banks | 166,744 | 163,090 | 223,079 | 27.0 | 21.6 | 23.7 | | Debentures | 247,864 | 334,383 | 405,261 | 40.1 | 44.2 | 43.1 | | - subscribed to by banks | 73,258 | 98,559 | 122,592 | 11.9 | 13.0 | 13.0 | | - subscribed to by others | 174,606 | 235,824 | 282,669 | 28.3 | 31.2 | 30.1 | | Other borrowings | 93,093 | 121,923 | 164,332 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 17.5 | | Public deposits | 74,222 | 86,573 | 93,143 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 9.9 | | Total | 617,761 | 756,451 | 940,365 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | | Source: National Housing Board's Report on Trend and Progress of Housing in India, 2018 | If ambitious targets of housing and housing ownership have to achieved, then banks and HFCs have to build funding models that have larger capacity ie can raise much larger quantum of funding, that are stable and reliable and with longer maturity. Securitisation can play an important role in allowing lenders to address the maturity mismatch issue. For smaller HFCs, securitisation can be a critical source of funding in situations where bank funding is constrained. Securitisation can contribute to making access to home loans wider and easier, thus supporting the achievement of targets of housing and home ownership. VII. Conclusion Housing is an economic and social priority for any society. The Indian government has publicly announced its aspirations of creating shelter for all by 2022 – the 75th year of India’s independence. Achieving this ambitious goal will require significant public and private investments. While the government will continue to create housing in both rural and urban areas for people, such construction will cater only to a small proportion of the underlying demand. A large proportion of the demand will have to be met by the private sector - private individuals buying from private builders and financed by various banks and HFCs. Creating a vibrant mortgage market and allowing a secondary market where mortgages can be sold to the appropriate risk-taking entities, will support the development of a stable funding model for the lenders, thereby significantly increasing the number of people who can access funding to own their homes. Such democratisation of home ownership will give people an incentive to be invested in their community. Many players will play a critical role in such democratisation including both banks and HFCs as the originators of the mortgage product. The emergence of specialised HFCs for the low-income and informal segments of the economy is an important trend that must be encouraged given the need for alternative under-writing approaches. Sustainable funding models will be especially critical here because these entities will, at least initially, have weak balance sheets, even if they have strong operations and under-writing. There are parallels here to the experience of Micro Finance NBFCs whose growth in the last decade has been fuelled by diversification of liabilities, including securitisation. While the relative shares of the banks and HFCs continue to change over time, HFCs are and will continue to remain especially critical in the unbanked segment. The funding sources for both entities hence need to be stable and reliable for achieving their business objectives while meeting the social objective of ‘Housing for All’. Chapter 3: Securitisation for Housing Finance: Opportunities and Challenges I. Introduction A securitisation transaction involves pooling loans of a kind, selling them to a special purpose vehicle (SPV), and issuing securities (pass-through certificates or PTCs) backed by the pool of loans. The flow chart in Chart 8 depicts a typical securitisation transaction. Key parties to any securitisation transaction are: -

The Originator is the entity that has made the original loan and is entitled to the receivable towards interest and principal repayments from the borrower. The originator is the entity that typically initiates the securitisation transaction and is a major beneficiary of it. -

The Borrower (alternatively called the Obligor) is the individual (or an enterprise) that has taken a loan from the originator and entered into contractual agreement with the originator to repay the interest and the principal. In case of secured loans, the Borrower also provides a collateral (a physical asset) as a security for the loan. In case of housing loans, the house that is bought with the loan is typically the collateral. -

The Investor is the entity (or individual) that buys the securities issued (ie the PTCs) by the SPV as a part of the securitisation transaction and could include banks, mutual funds, insurance companies, pension funds, alternate investment funds, etc. -

The Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) is an entity specifically created for the securitisation transaction. It buys the pool of assets from the originator and issues securities to the investor. It can be a company, a partnership firm, or a trust. Most commonly, the SPV is a trust. -

Facilitator for credit enhancement is an entity that provides credit enhancement to the securities issued by the SPV in order to improve their ratings. Any shortfall in the cash flows from the securitised pool is made up by funds from the credit enhancement facilitator. -

Servicer is the entity that services the loan pool after it has been securitised. Servicing primarily involves collecting interest and principal repayments from the borrowers, dealing with delays or defaults, enforcing security interest where necessary and operational issues such as issuing statements and tax certificates to borrowers. Servicing can be provided by a third party servicer, which is an independent entity that provides this service. However, in India, in almost all cases of securitisation, the originator continues as the servicer. In addition to the key parties depicted in the flow-chart and described above, some other entities play an important role in the securitisation transaction. They include: -

Rating agencies who provide the credit rating for the securities issued, and in the process of doing so, determine the extent and the nature of credit enhancement needed in order to support the ratings. -

Trustees (of the SPV Trust) oversee the performance of all the parties and supervise the distribution of cash to the investor. The asset pool is created by pooling loans that are similar in nature, and regulations impose a homogeneity condition on the loan pool. Securitised loans could include unsecured loans such as micro finance loans, or secured loans such as housing loans, auto loans, etc. All securitisation transactions have some essential features: • Under securitisation regulations, the sale of the asset pool from the originator to the SPV must be a ‘true sale’ so that all the benefits and obligations of the underlying loans are transferred to the SPV and the loans in the pool are removed from the balance sheet of the originator. The originator can continue to remain the ‘servicer’ for the SPV, collecting repayments from the borrowers in the pool but bears no risk and gets no reward from the performance of the pool, except for the part it retains as per regulatory requirements. • The transaction is ‘bankruptcy remote’ which means that in the event that the originator of the loans in the pool becomes insolvent and undergoes bankruptcy process, the asset pool that underlies a securitisation transaction, is excluded from the process of resolution or liquidation of assets of the originator. • All the payments to the security holder are ‘pass through’ from the underlying pool. The special purpose vehicle (SPV) does not alter the payments and merely collects them and allocates them to the various classes of security holders as per the norms laid down as a part of the securitisation transaction. • Securitisation structure often includes credit enhancement arrangement that is needed to improve the credit rating of the securities that are issued. The nature and the extent of credit enhancement is determined by the rating agencies as a part of the rating process of the PTCs. Credit enhancement can be of two types – external or internal. External credit enhancement is one where the exposure of credit risk is created on counter-parties other than the borrowers of the loan. Such credit enhancement can be provided through a cash collateral where a cash deposit is made into an account which is accessed only by the trustee of the securitisation who can draw on it to make up for any shortfall in the investor payouts. Alternatively, the external enhancement is provided through a guarantee issued by a bank or a corporate. The trustee for the securitisation sends a notice to the guarantor in the event of any shortfall in the investor payouts and the guarantor is expected to make up the shortfall. Internal credit enhancement is one where the enhancement arises from the structure of the securitisation transaction. There are two ways such enhancements can be provided – through subordination and over-collateralization and through ‘excess interest spread’. Subordination is achieved in a securitisation transaction when the securities are issued in ‘tranches’ with different seniorities of claim on the cash flows from the underlying loan pool. The senior tranches have first claim on the cash flows. The junior tranches, thus, by subordinating their claim on the cash flows enhance the credit quality of the senior tranches. Subordination is commonly referred to as ‘credit tranching’. ‘Excess interest spread (EIS)’ arises if there is a positive difference in the payments received from the pool and the payouts committed to the investors ie the cash-flows from the pool exceed the payouts to the investors. Any such difference in the cash flows accrues with the originator and can be used to meet any shortfall in payouts to the investor that may arise later, as a part of credit enhancement. Credit enhancement is often structured in a tiered manner where the ‘first loss’ credit enhancement is triggered before the ‘second loss’ credit enhancement. It is quite common for the originator to provide the first loss credit enhancement (FLCE) through cash collateral and to get a third party (a bank or an insurer) to provide the second loss credit enhancement (SLCE) through a guarantee. In such a setup, any short fall in the payouts will be first met by the FLCE and only when it is exhausted the SLCE is invoked. • Issuance of securities (the pass through certificates) could occur in separate tranches. The tranches can be of two type – time tranches and credit tranches. Time tranches are securities issues with varying maturities. Credit tranching is based on subordination that is a form of internal credit enhancement and involved issuance of securities with varying seniority of claims on the underlying cash flows (discussed above). In India, credit tranching is quite common while time tranching is rare. II. Overview of securitisation regulation in India Securitisation is relatively recent in India. Until 2006, there were no formal regulatory guidelines for securitisation. There were no formal securitisation transactions prior to 2006. Reserve Bank of India issued its first securitisation guidelines in February 2006. These guidelines were foundational in that they set out the broad framework for securitisation. Specifically, the 2006 guidelines: -

Described the securitisation process and the role and obligations of all key participants – originators, SPV, credit enhancement and liquidity providers -

Established baseline criteria for true sale, SPV construction, credit enhancement, liquidity provision, underwriting, representations and warrantees, etc -

Defined prudential norms for investments in securities issued by SPV -

Set out accounting treatment and income recognition norms -

Set out disclosure requirements for all the parties In 2008, the world faced a financial crisis that had its roots in the American housing and housing finance markets. The whole process of securitisation and the role of agencies engaged in it came under scrutiny as the financial sector regulators across the world reacted to the gaps and shortcomings in regulations revealed by the crisis. Although, Indian financial sector did not suffer any direct impact from the global financial crisis, Indian financial sector regulators tweaked regulations to avoid similar crisis from occurring in the country. RBI issued modified securitisation guidelines in May 2012 that were intended to be a revision and extension of the 2006 guidelines. These guidelines: -

Establish the minimum retention requirement (MRR) and minimum holding period (MHP) standards. -

Established the limits on total retained exposure by the issuer -

Provided guidelines on the treatment of profits booked upfront -

Refined disclosure norms -

Established standards for loan origination, due diligence, stress testing and credit monitoring -

Provided baseline guidelines for DA transactions One important feature of these guidelines is that it includes two different types of transactions under securitisation – the Direct Assignment (DA) transaction and the Pass-through Certificate (PTC) transaction. A DA transaction involves originator entity pooling loans and then selling them to another entity. Essentially, both DA and PTC transactions involve transfer of credit risk in a loan pool between two entities. However, there are two crucial differences between DA and PTC transactions. In a DA transaction, no intermediary (such as an SPV) is involved and the transaction is between the seller of the loan pool (ie the originator) and the buyer (ie the investor). Further, no securities are issued in a DA transaction. DA transaction, thus, does not fit within the generally accepted definition of securitisation. The MRR and MHP were the most important features of the 2012 guidelines and were influenced by the global financial crisis. MRR defines the minimum amount of ownership of the pool that the originator must retain in a securitisation transaction. It is, in essence, the originator’s ‘skin in the game’ even after most of the risk in the loan pool has been transferred. MHP defined the minimum length of time that a loan must stay on the books of an originator before it can become a part of a pool that will be securitised. MHP is essentially an instrument to avoid ‘originate to distribute’ model being followed by an originator; making a loan and immediately securitising it. The 2006 and 2012 guidelines together describe the regulatory regime governing securitisation in India. In addition to these major regulations, there have been a few others that dealt with specific aspects of securitisation. Most notably, July 2013 guidelines defined the rule of reset of credit enhancement over the life of the securitisation transaction and the January 2018 guidelines laid out the rules for foreign investors for investing in securities. In 2015, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision issued comprehensive framework for securitisation. This framework (called the Basel III securitisation framework) aims to provide standards for financial sector regulators for treatment of securitisation transactions. If broadly convers three aspects – (1) definition of the requirements for credit risk transfer on originator that should result in de-recognition of the asset pool underlying securitisation from the originator’s balance sheet (2) computation of capital requirements for entities that have exposure to securitisation, and (3) capital treatment for what it calls ‘simple, transparent, and comparable (STC)’ securitisation. Only Europe has adopted the Basel standards with some modification to capital requirements for securitisation exposure. Several other jurisdictions (eg Australia) have adopted some aspects of the framework while the US and China have not adopted these standards at all. We discuss the issue of implementation of the Basel framework in India later in this report. III. Growth of Securitisation in India Since the first securitisation guidelines were issued in 2006, the volumes of securitisation have seen significant growth in India. The total volume of securitisation increased from ₹23,545 crore in financial year 2005–06 to ₹266,264 crore in the financial year 2018–19, an eleven–fold growth in 13 years. While the overall securitisation volumes have grown strongly in the last few year, the growth was driven largely by DA transactions. PTC’s are less than a third of the overall securitisation volume. In the financial year 2019, which saw very strong growth in securitisation, primarily driven by liquidity challenges in the NBFC / HFC segment, only about a quarter were PTC transactions. Of these, mortgage backed PTCs were merely ~two per cent. Large proportion of DA transactions suggests that the buyers / investors in these transactions would be entities with balance sheets – mostly banks and some NBFCs. Other pools of capital – mutual funds, insurance, pension funds, and individuals have not been significantly participating in securitisation. This is especially true for mortgage-backed securitisation, where there is virtually no participation of the non-bank capital pools. IV. Securitisation for Housing Finance (Home Loans) Buying or building a home is the largest expense for most individuals. Borrowing money for home buying is, thus, very common. In India, commercial banks and housing finance companies (HFCs) have been the providers of home loans. Home loans are the longest maturity assets issued by any lender. Most home loans have a contractual maturity of 15 to 20 years and it can go as high as 30 years for younger borrowers. While prepayment of the home loan is very common, even after adjusting for prepayments, these home loans could have actual maturity of eight to 10 years, which is still the longest in the loan books of most lenders. Long maturity of home loans creates a structural asset liability management (ALM) challenge for the lenders – lenders do not have funding sources that can match such a long maturity of these loans. HFCs, which rely on a mix of bank borrowings and bond issuance, can borrow with maturity that does not typically exceed five years. Banks have access to public deposits but even for them a large proportion of these deposits have contractual maturity of less than three years. As the share of home loans in the overall credit book of banks grows over the coming years, even banks will start facing increasing pressure to manage this ALM challenge.  Chart 10 depicts maturity profile of term deposits of Indian banks over the last 13 years. It clearly shows that long term deposits – over the maturity of five years are just about 15 per cent of the total deposits, and deposits with maturity of less than two years are nearly two thirds of the total term deposits. Thus, the banking sector liabilities are predominantly short term relative to the maturity of the home loans.  Chart 11 shows the asset liability maturity profile of a sample of housing finance companies. It is clear that they are funding long-term assets through short-term liabilities and this trend has become more pronounced in the last few years. Presently there are over 100 registered HFCs in India. Of these, top five have over 85 per cent share of the housing loans from HFCs. There is a long tail of several small HFCs who primarily focus on servicing economically weak and geographically dispersed customer segments. These small NBFC do not have access to debt capital markets and rely almost entirely on funding from banks. The ALM challenge faced by them is even more acute than that for the larger HFCs and hence diversifying the sources of funding is much more critical for them. This structural ALM challenge can be addressed by the lenders in two ways. The first is pricing – making most loans ‘floating rate’ reduces the pricing risk posed by asset liability mismatches. It also reduces the probability of pre-payment in the event of downward movement in interest rates, relative to ‘fixed rate’ loans. Floating rate pricing, however, does not address the funding challenged posed by the asset liability mismatch. For this, maturity of assets has to be matched by the maturity of liabilities in order to ensure stable funding of the loan book. For home loans, thus, the lender needs liabilities that can have maturity matching the effective maturity of home loans, which could be eight to 10 years. However, as the data above shows neither HFCs nor even banks have such long maturity sources of liabilities. There are two mechanisms that this maturity mismatch can be addressed – by accessing long maturity liabilities with other types of financial institutions to fund home loans and by reducing the ‘holding period’ maturity of the home loans. Both these mechanisms can be delivered through securitisation. In the financial system, the institutions that has the longest maturity liabilities are life insurers and pension funds. Both insurance companies and pension funds can invest their funds into securities issued through securitisation of home loans. A well-developed secondary market can impart liquidity to these securities that will also reduce the holding period maturity for the investor. Thus, in addition to emerging as a reliable source of funding to complement existing sources, securitisation of home loans can play a crucial role in addressing the structural asset liability management challenge faced by lenders of home loans. This will be critically important for small and new HFCs, especially those that focus on the lower income customer segment. Securitisation for housing finance will mean pooling of housing loans (home loans), selling them to a SPV, and then issuing securities backed by these loans to investors. There are some critical differences between securitisation of housing loans (more commonly called ‘mortgage-backed securitisation (MBS)’) and that for other kind of loans such as micro finance loans, auto loans, etc. -

Home loans are generally of much longer maturity (up to 25 years) than these other loans which mature typically within five years -

The underlying security for home loans is much stronger and is on stronger legal foundations through creation of the mortgage than for the other types are loans which are either unsecured or are secured with a charge on moveable assets -

The value of underlying security ie the property in the case of MBS generally appreciates increasing the security cover for the PTCs over their life unlike other asset backed securities where the value of the underlying security depreciates over the life of the loan -

The ratio of loan to value (LTV) for home loans generally tends to be lower than for other classes of loans such as vehicle loans -

The performance of home loans as an asset class in terms of levels of non-performing assets (NPAs) across business cycles is much better than other types of loans Given these differences, if can be argued that securities issued through securitisation backed by housing loans are a fundamentally different asset class from securitisation for other types of loans, and should be treated differently. V. Committee’s Approach The mandate for this Committee is to comprehensively review securitisation for housing loans and make recommendations for its development and growth. The Committee has taken a longer-term view where securitisation can develop as a reliable, stable, safe, and large source of funding for housing loan providers. Data on securitisation in India clearly highlights two skews – (1) the domination of DA transactions, especially in housing loans, and (2) the domination of banks (and some large NBFCs) as investors. As has been explained earlier, DA is not a true securitisation transaction. The preponderance of DA as preferred model of securitisation can be attributed to the need for banks as investors to build their loan book; DA assets become a part of the loan book while investments in PTCs are a part of the investment book. Furthermore, a significant proportion of DA transactions are motivated by the banks’ need to acquire asset pools that qualify under the priority sector obligations. On the originator side, the transactions are often driven by liability side considerations, more so during times of funding constraints. Some of the recent regulatory developments like co-origination of loans with banks and finance from banks for on-lending to certain sectors are likely to mitigate their funding needs. Development of securitisation for housing finance must address this skew in the current securitisation model. It must (1) create economic incentives for participants to pursue securitisation all types of housing loans and not just those that fall under the priority sector definition, (2) move the participants away for DA to PTC, and (3) attract broader pools of capital beyond banks. Securitisation should develop as a reliable source of funding a complement and not a substitute to the current funding sources. With these overall objectives in mind, the perspective that guided the Committee’s thinking on mortgage-backed securitisation is that of promoting efficiency and transparency of the transaction so that all the participants find it in their economic interest to pursue the transaction. Increasing efficiency in a securitisation transaction will mean reducing transaction costs. Transaction costs arise from the intrinsic nature of the transaction –activities and documentation, actual financial costs involved in providing credit enhancement, etc. Transaction costs also arise from legal and regulatory requirements that the transaction must meet. The Committee’s approach was to look at all the possible sources of transaction costs and make recommendations to minimize them without compromising on the robustness of the transaction. The Committee was acutely aware of the risks inherent in a securitisation transaction and ensured that while making recommendations to reduce transactions costs the risks in the transaction will not be amplified. Transparency in the securitisation transaction is critical for all the stakeholders in the transaction – the originator, the investor, the trustees, regulators, rating agencies, etc – to develop confidence in it. Presently, almost all securitisation transaction in India, whether under DA or PTC, are customized bilateral transactions between the originator (the seller) and the investors (the buyer). The buyer performs extensive diligence on the securitisation pool that the seller offers and they engage in extensive discussion on valuation. Such bilateral transactions are not scalable. They also rule out from participation those ‘arms–length’ capital pools that have neither the appetite nor the ability to engage in such an extensive diligence process. In order to scale and be a relevant source of funding, securitisation process must attract broader capital pools. It has to match the level of transparency in the issuance of other instruments such as equity and bonds. The Committee reviewed all aspects of securitisation from the point of view of enhancing transparency and considered opportunities of standardisation as well as disclosures as instruments of transparency. The committee, thus, took a comprehensive view of the entire life cycle of securitisation. In addition to looking at the issues faced by the originators and the investors, the Committee also looked at some enablers that do not directly affect a securitisation transaction but could significantly influence the development of securitisation in India. In addition to short-term issues, the Committee also reviewed longer term institutional development issues that will have to be addressed in order to realise the growth and development of housing finance securitisation. The conceptual approach of the Committee is depicted in Chart 12. There are two main stakeholders in a securitisation transaction – the originator and the investors. In addition to the issues faced by these main stakeholders, there are other enablers that can influence the securitisation transaction. Across these three broad buckets run a wide range of topics that the Committee reviewed – legal and regulatory issues, accounting and taxation related issues, issues related to secondary market development, issues related to data and information, etc An alternative to securitisation is the so-called ‘covered bond’, which has gained some popularity, especially in Europe. A covered bond is a bond that is secured by a pool of assets on the originators balance sheet. Like in securitisation a distinct pool of assets (ie loans) that is ring-fenced from the rest of the assets of the originator provides security to the bond. However, unlike securitisation, the pool remains on the balance sheet of the originator and is not transferred to an SPV. The most attractive feature of the covered bond is that it allows banks to issue secured debt. In most jurisdictions (including India), banks as depository institutions are not permitted to issue secured debt. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, most banks in the US and Europe witnessed significant downgrades in their ratings making it very hard for them to access funding through unsecured bond issuances. Covered bonds provided an avenue to issue bonds with much higher ratings as they were backed by a distinct and high rated pool of assets. The Committee carefully considered if it should review covered bond issuance and make any recommendation. It decided not to do so for two reasons; First, banks in India have not faced a challenge in bond issuance that should lead them to demand an instrument like covered bond. Prohibiting or permitting secured debt issuance by banks is a much a larger regulatory issue that did not fall within the remit of the Committee. Second, HFCs have been permitted issuance of secured debt and have been doing so, and hence issuance of covered bonds does not add any significant flexibility to their funding model. The Committee primarily focused on PTC model of securitisation. While many of the recommendations made with PTC transaction in mind can be extended to the DA transactions, the Committee did not review issues that specifically arise only in the DA transactions. Securitisation for housing finance could include pooling of housing loans as well as loan against property (LAP) where the property is residential. For the purpose of the Committee’s discussions, the focus has been on pooling of home loans (mortgages) and not LAP. This report uses the term mortgage-backed-securitisation (MBS) interchangeably with securitisation for housing finance. In Chapter 4, we review international experience in mortgage-backed securitisation and draw some lessons for India. In Chapters 5 and 6 we provide a summary of all the key issues related to originators and investors in a securitisation transaction, and make recommendations that will drive efficiency and/or transparency in the transaction. Chapter 7 reviews the important enablers that could play a catalytic role in the development of mortgage-backed securitisation in India. Chapter 8 offers an implementation path, essentially identifying the agencies that need to act on specific recommendations. Chapter 4: International experience in developing a housing securitisation market I. Introduction Many markets around the world are ahead of India in the development of their mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market. Their experiences and the path of development have been diverse. A few have started and soared, some have not taken off sustainably, and the others have learnt important lessons and made changes along the way. The 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), in particular, was a watershed event, which forced many regulatory and system wide changes across MBS markets. The evolution of MBS in other countries provides a rich source of experience and learning for India. In this chapter, we focus on five specific issues, which any country trying to develop its MBS market will have to grapple with. These issues are: -

Structure, state support and catalysts for take-off -

Secondary Market Models -

Accompanying regulation -

Data and process standardisation -

Qualifying criteria for securitisation Within each issue, we discuss the experience of select countries, such as the US, South Korea, Malaysia and Colombia. Our study helps us filter specific implications for developing India's MBS market. Towards the end of the chapter, we summarize our key lessons for India from the international experience. II. Structure, State Support and Catalysts for Take-off Securitisation is an intermediated transaction. The intermediary plays a crucial role in executing the transaction, and core functions vary by country. We focus on the specific intermediary model adopted by a host of countries that have experienced some success in growing the MBS market. We discuss the different kinds of state assistance, ranging from state ownership to tax breaks, and highlight their pros and cons. We identify the factors that tend to act as catalysts to enable the sector to take off. We divide this section into three models of MBS with varying state guarantee - (A) strong state guarantee, (B) weak or implicit state guarantee, and (C) no state guarantee. II.A. Strong State Guarantee: The Case of United States of America (US) The US is an important case study as it highlights possible pitfalls that led them into the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC). They are also a good study for the changes that were made post-2008, on the back of which, the market for MBS has revived. The three main MBS agencies in the US are Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association, FNMA), Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, FHLMC), and Ginnie Mae (Government National Mortgage Association, GNMA). These ‘agencies’ are government or government-sponsored enterprises (GSE) created by the Congress to ‘support the mortgage market’. Together, they cover ~90 per cent of the US MBS market. The remaining 10 per cent, known as 'non agency', are intermediated by private sector players without implicit/explicit state guarantee. The agencies provide credit guarantees to mortgage investors, effectively replacing the borrower’s credit with their own. Any MBS facilitated by one of these three entities is called ‘Agency MBS’. The agencies charge a fee to provide this credit wrap, which essentially functions like an insurance premium. If the borrower defaults, the agency will make up the shortfall in the investor payout. These agencies were in spotlight during the global financial crisis. Many believed them to have contributed to its start and spread. Careful analyses of the causes and consequences of the crisis revealed that poor consumer protection allowed risky, low-quality mortgage products, and predatory lending to proliferate. Inadequate regulatory regime failed to keep the system in check. A complex securitisation chain lacked transparency, standardisation, and accountability. Inadequate capital and lack of credit risk transfer left financial institutions unprepared to absorb the losses. Also, the servicing industry was ill equipped to serve the needs of borrowers, lenders, and investors, once housing prices fell. Recognition of these shortcomings resulted in significant reforms to the functioning of these agencies as well as the regulatory oversight over them. State support. Ginnie Mae is formally a part of the U.S. Government. Securities guaranteed by Ginnie Mae have an explicit guarantee from the US government. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are not part of the US government, but because they are created by Congress, they are referred to as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Securities guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac are said to have an implicit guarantee from the U.S. Government. On September 6, 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were taken into conservatorship by the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). Catalyst for take-off. Despite the 2008 crisis, the Agency MBS market in the US is large, at US $6.7 trillion in March 2019. (The non-agency MBS market is about US $0.5 trillion). Prior to the 2008 crisis, the main catalyst for their growth was the explicit and implicit state guarantees. Since the crisis, several important changes have been made, which have allowed the MBS market to develop again. Some of the changes are as follows: -

Taking the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into conservatorship brought in stability right after the fallout, albeit at a large fiscal cost -

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, 2010 has modernised the regulatory structure, making it much stricter than before. One of the steps is to mandate a 5 per cent credit risk retention, so that the sponsor has skin in the game. -

Tightly defined ‘Ability to Repay’ criteria and ‘Qualified Loans’ have harmonized and upgraded data and process standards -