General public and the stakeholders are requested to furnish their specific and actionable comments by 15th April 2016 to the Chief General Manager, Department of Payment and Settlement Systems, Reserve Bank of India, Central Office, 14th Floor, Shahid Bhagat Singh Marg, Fort, Mumbai – 400 001. Comments may also be furnished by email by 15th April 2016. PREFACE The Reserve Bank of India (the Bank) has been encouraging reforms in the payment and settlement systems of the country, leveraging on the benefits derived from developments in technology. The policy and regulatory framework addresses the need to put in place a bouquet of payment options both for individual as well as institutional users while addressing the safety and security requirements of the systems and the users. The Bank has also been sharing and signalling the desired developments in payment and settlement systems in the country through its Payment Systems Vision Documents. An over-arching Vision for payment systems in recent times has been the need to ensure greater adoption of electronic payments and migrate towards becoming a “less-cash” society. The efforts of all stakeholders have resulted in a growing trend in electronic payments. The question of importance is whether further developments in this regard should be left to the users themselves (market forces) or whether this growing trend should be “managed” through appropriate policy framework. While market-forces led growth may address the “economics” of the payments eco-system, it may not always meet the requirements of all segments of users. A structured policy intervention to promote electronic payments may have the advantage of not only addressing the requirements of all sections of society but also enable setting of achievable targets within a definite time-span which can be monitored, reviewed and changed, if necessary. The Reserve Bank of India has prepared this concept paper on policy framework for expansion of card acceptance infrastructure in the country in consultation with a few stakeholders. The paper outlines the broad contours of a multi-pronged strategy to enhance the growth in acceptance infrastructure and usage of cards including further rationalisation of merchant discount rates (MDR) or merchant fees for debit card transactions. In the Fourth Bi-monthly Monetary Policy Statement, 2015-16 it was announced that in order to promote electronic payments and use of cards for transactions, the Reserve Bank will put in the public domain a concept paper for proliferation of card acceptance infrastructure in the country, especially in the tier III to tier VI centres. Chapter - 1

Introduction 1.1 The use of electronic channels for accessing banking and payment services is on the rise and is poised for significant growth in the country. The Reserve Bank has been initiating new policies as well as reviewing existing policy measures for facilitating demand and supply of electronic payment services and also ensuring safety and security of such transactions. Recent announcements of the Government also support and reinforce the migration from cash payments to promotion of card and other electronic payments. 1.2 In the eco-system of electronic / alternate payment mechanisms, card payments are perhaps most recognizable. Further, the developments in e-commerce sector have also been significant in encouraging electronic payments, including card payments (credit/debit), which are gradually gaining significance. With the implementation of Prime Minister Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), the card issuance under RuPay network has seen a tremendous growth in a short span of time. Given the high issuance of debit cards to accounts opened under the PMJDY, with benefits to account holders linked to usage of their RuPay debit cards, the imperative to ensure greater usage of cards as well as enhance growth of infrastructure is significant. 1.3 Card payments include payments made using debit cards, credit cards or prepaid / stored value cards. Further, card payments could be done face-to-face (card present / proximity payments) or carried out remotely (card not present / online payments). In all situations, card payments involve a card holder, a merchant / entity with infrastructure to accept card payments, a bank/institution which issues the card and a bank/institution which sets up the infrastructure for accepting card payments. 1.4 As such, even as the growth in ATM infrastructure may be necessary in the short and medium term to meet the cash requirements of consumers, the focus of this paper is on card payments and possible strategies to enhance its acceptance as a means of payment for purchase of goods and services including increasing the growth of related acceptance infrastructure. Policy framework for safety and security of transactions 1.5 In the context of encouraging card payments and also to ensure that safety and security requirements of card transactions provide the necessary confidence to its users, the Bank has put in place specific policy measures over the last few years for both card-present (CP) transactions (face-to-face, proximity payments) as well as card-not-present (CNP) transactions (remote, online payments). 1.6 Some of these measures include: -

Online alerts to the cardholder for all card transactions – both CP and CNP transactions irrespective of value of transaction to alert customers for transactions done using their card/s; particularly in case of fraudulent transactions, customers are made aware immediately so that preventive / corrective steps can be taken by them immediately; -

Requirement for additional factor of authentication (AFA) for all CNP transactions to authenticate transactions based on information that the customer alone is supposed to know; -

Requirement of PIN@POS for all card present transactions using debit cards to prevent usage of cloned cards and to authenticate transactions with the PIN which the customer alone is supposed to know; -

Issuance of cards for international usage only on specific request by customers, and if issued, it has to be EMV chip and PIN card to prevent fraudulent usage of cloned magnetic stripe cards or online use of cards in other countries where AFA is not required / mandated; -

Setting threshold value for international transactions done using existing magnetic stripe cards enabled for international usage so as to reduce / minimise loss in case of fraudulent use of such cards; and -

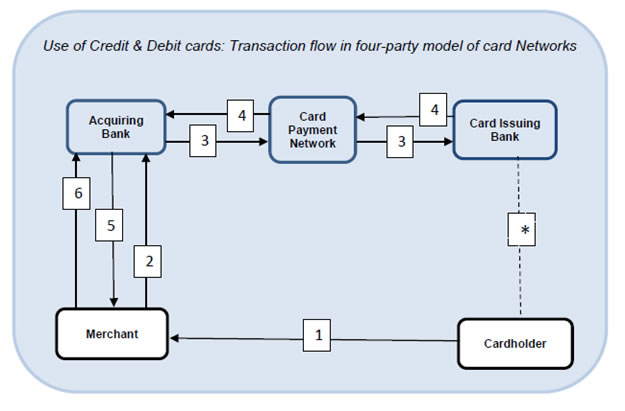

Migration of all cards to EMV Chip and PIN to reduce fraudulent use of cloned cards and increase safety in CP transactions Extant regulatory framework for MDR 1.7 In order to encourage all categories of merchants to deploy card acceptance infrastructure and also to facilitate acceptance of small value transactions through card payments, the Reserve Bank had rationalized the Merchant Discount Rate (MDR)1 for debit cards with effect from September 2012. 1.8 Since then, the MDR for debit card transaction has been capped at 0.75% for transaction values upto Rs.2000/- and at 1% for transaction values above Rs.2000/-. Card transaction: Illustrative Work Flow 1.9 In order to appreciate the economics of card payments, it may be useful to have a perspective on the entities involved in a card transaction and the generic work flow in a card transaction. Entities involved in the transaction: -

Merchant location: Entity selling goods and services -

Acquiring Bank: The bank which has installed the POS terminal at the merchant location -

Card network: RuPay/ Visa / MasterCard, etc. (transaction routing and settling agency) -

Customer / Consumer: Cardholder -

Issuing Bank: The bank which has issued the card to the customer Type of transactions:

-

A consumer purchases some goods / services and uses a debit / credit card to pay the merchant. -

The merchant (terminal) sends the encrypted transaction data to the acquiring bank system / switch for authorization. -

The acquiring bank sends the transaction data to the consumer’s (card issuing) bank over the card payment network. -

The issuing bank authenticates the card / cardholder details; based on successful authentication and after checking availability of balance (for debit card) or credit limit (for credit card) authorizes the amount and issues an authorization code or declines the transaction. -

The acquiring bank notifies the merchant that the transaction either has been authorized or declined; the merchant then completes the transaction (if successful, then print receipt and hand over the goods, etc.) -

Subsequently, the merchant, through the acquiring bank, will claim the settlement for funds. The inter-bank settlement (between issuing bank and acquiring bank) will take place through the card network. * In case of debit card, the customer’s account is debited by the card issuing bank after authentication of the credentials and if balance is available; in the case of credit card, the bank will reduce the available credit limit in the customer’s card account and the same will be reflected in the credit card statement. Economics of card payments 1.10 Any policy framework structured to drive acceptance of card payments both from merchant as well as from the consumer side, has to balance the concerns, issues and challenges arising from all stakeholders. The economics of card payments has significant costs and benefits to all stakeholders, a brief outline (illustrative but not exhaustive) of which is given below: Benefits of electronic / card payments: 1.11 The benefits accrue not only to individual users of card payments but also have potential of benefits for the economy as a whole by: -

Providing faster, more secure and convenient way of payment for purchase of goods and services; -

Reducing in cash handling costs leading to increased savings; -

Lowering transaction costs through greater operational efficiency; -

Facilitating better financial intermediation; and -

Providing greater financial transparency by enabling recording of all economic activity, helping in reducing the proliferation of grey economy and increasing tax revenue. Costs and issues associated with card payments: 1.12 Even though there is the potential to reap the above benefits, there are certain costs and issues that are associated with card payments which inhibit their greater adoption. Some of these are outlined below for different stakeholder segments: -

Merchants – costs related to payment of merchant fees, transparency and taxation, KYC documentation, certification process related to safety and security of transactions/systems, etc. Other issues that act as deterrents include the fact that there could be various stages in supply chain where cash payments are still made; through cash payments transactions are completed immediately whereas settlement of card payments takes some time for processing; etc. -

Consumers – annual fees for cards, levy of convenience charges / surcharge on use of cards, feel of convenience generally associated with cash payments, etc. Other related issues pertain to safety and security concerns, fraud protection mechanisms, concerns regarding consumer grievance redressal mechanism, etc. Last but not the least is the lack of availability of card payment option especially where the consumer spends for day-to-day personal consumption. -

Card issuing banks – costs associated with card issuance, replacement / maintenance, ensuring security requirements at all times, system for addressing consumer complaints and grievances, education and marketing, promotions, putting in place risk and fraud monitoring systems, processing chargeback claims and fraud liability, etc. -

Merchant acquiring banks – costs related to acquiring merchants including capital cost of equipment and maintenance, integration with merchant systems, ensuring compliance with certification, education and training, etc. In addition, investment and constant upgradation of security and risk management systems, fraud protection (underwriting risk), credit evaluation risk, regulatory compliance, etc. are also issues that acquiring banks have to deal with. 1.13 The subsequent chapters address the various issues coming in the way of enhancing the usage and acceptance of card payments, and examine certain strategies that may facilitate in enhancing the card payments infrastructure. Chapter - 2

Issues in Card Payments 2.1 Though there is significant increase in electronic transactions, the growth is not uniform across all segments of electronic payments nor is it visible at all locations across the country. Particularly, in the context of cards, while the card base is increasing rapidly, activation or usage rates are quite low, especially for purchase of goods and services. Card usage at ATMs, on the other hand, is quite high. 2.2 Thus, with the substantial growth in the issuance of the cards, there is an urgent need to ensure quick, equitable and sustainable growth in card acceptance infrastructure across the country. Further, along with the measures to increase availability of card acceptance infrastructure it is also essential to ensure that cards payments are accepted seamlessly for all types of payments irrespective of amounts. Growth in cards and acceptance infrastructure 2.3 The tables2 below indicate the position regarding card issuance, growth of card acceptance infrastructure (ATM as well as POS machines), and card usage in the country for last three years: | Table 2.1: Growth in Card Issuance | | Category of Bank | No. of Debit Cards (in mn) as on | No. of Credit Cards (in mn) as on | Oct'13

(% of Total) | Oct'14

(% of total) | Oct'15

(% of total) | Oct'13

(% of Total) | Oct'14

(% of total) | Oct'15

(% of total) | | Public Sector Banks | 299.31

(79.99) | 356.94

(80.83) | 513.26

(83.41) | 3.68

(19.83) | 3.95

(19.80) | 4.74

(20.71) | | Private Sector Banks | 71.50

(19.11) | 81.49

(18.45) | 99.02

(16.09) | 10.05

(54.08) | 11.31

(56.67) | 13.42

(58.64) | | Foreign Banks | 3.37

(0.90) | 3.17

(0.72) | 3.07

(0.50) | 4.84

(26.09) | 4.69

(23.53) | 4.73

(20.65) | | Total | 374.18 | 441.6 | 615.35 | 18.57 | 19.95 | 22.88 | | (figures in brackets indicate percentage share in total cards issued) | 2.4 While debit cards registered a growth of 64% between Oct 2013 and Oct 2015, credit cards grew at 23% during the same period. As at end-December 2015, the total number of credit cards stood at 22.74 million while debit cards stood at 636.85 million cards in the country. | Table 2.2: Growth in Card Acceptance Infrastructure | | Category of Bank | No. of ATMs as on | No. of PoS machine as on | Oct'13

(% of Total) | Oct'14

(% of total) | Oct'15

(% of total) | Oct'13

(% of Total) | Oct'14

(% of total) | Oct'15

(% of total) | | Public Sector Banks | 85,748

(64.32) | 1,22,324

(70.42) | 1,36,682

(71.61) | 1,76,349

(18.30) | 2,55,649

(23.00) | 4,06,373

(32.85) | | Private Sector Banks | 46,334

(34.76) | 50,229

(28.92) | 53,108

(27.83) | 7,32,443

(76.02) | 8,02,236

(72.17) | 7,81,763

(63.20) | | Foreign Banks | 1,231

(0.92) | 1,144

(0.66) | 1,069

(0.56) | 54,699

(5.62) | 53,691

(4.83) | 48,797

(3.94) | | Total | 1,33,313 | 1,73,697 | 1,90,859 | 9,63,491 | 11,11,576 | 12,36,933 | | (figures in brackets indicate percentage share in total ATMs and POS) | 2.5 Between Oct 2013 and Oct 2015, ATMs increased by around 43% while POS machines increased by around 28%. As of end-December 2015, the number of ATMs has increased to 193,580 while POS machines had increased to 1,245,447 in the country. | Table 2.3: Debit card usage | | Debit Card Usage | 2012-13

(April – March) | 2013-14

(April – March) | 2014-15

(April – March) | Volume

(mn) | Value

(bn) | Volume

(mn) | Value

(bn) | Volume

(mn) | Value

(bn) | | Debit card Usage at ATMs | 5530.16 | 16650.08 | 6088.02 | 19634.54 | 6996.08 | 22278.64 | | Debit card Usage at ATMs (as % of total debit card usage) | 92.18 | 95.73 | 90.77 | 95.37 | 89.65 | 94.83 | | Debit card usage at POS | 469.05 | 743.36 | 619.08 | 954.09 | 808.06 | 1213.42 | | Debit card usage at POS (as % of total debit card usage) | 7.82 | 4.27 | 9.23 | 4.63 | 10.35 | 5.17 | 2.6 During the current year too, from April 2015 to December 2015, the usage of debit cards at ATMs continues to account for around 88% of the total volume and around 94% of total value of debit card transactions. Usage of debit cards at POS machines accounts for only around 12% of total volume and 6% of total value of debit card transactions. This is despite the fact that between FY2012-13 and FY 2014-15 the debit card usage at POS machines registered a growth of 72% in terms of volume and 63% in terms of value. | Table 2.4: Credit card usage | | Credit card usage | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | Volume

(mn) | Value

(bn) | Volume

(mn) | Value

(bn) | Volume

(mn) | Value

(bn) | | Credit card Usage at ATMs | 2.52 | 14.42 | 2.96 | 16.87 | 4.3 | 23.47 | | Credit card Usage at ATMs (as % to total credit card usage) | 0.63 | 1.16 | 0.58 | 1.08 | 0.69 | 1.22 | | Credit card usage at POS | 396.61 | 1229.51 | 509.08 | 1539.85 | 615.13 | 1899.15 | | Credit card usage at POS (as % to total credit card usage) | 99.37 | 98.84 | 99.42 | 98.92 | 99.31 | 98.78 | 2.7 During the current year from April 2015 to December 2015, credit card usage at ATMs accounted for around 0.73% of volume and 1.25% of value of total credit card transactions. Use of credit cards for POS transactions accounted for 99.27% of volume and 98.75% of value of total credit card transactions in the country. Observations 2.8 Based on the above data and also some additional inputs obtained from the stakeholders, the following observations can be made on the present status of card usage and deployment of acceptance infrastructure: -

Debit cards vastly outnumber the volume of credit cards issued in the country. Further, a high number of debit cards have been issued in recent times under the PMJDY, especially to customers in rural areas and smaller towns. -

The growth in acceptance infrastructure has not kept pace with the growth in cards. While debit cards registered a growth of 64% between Oct 2013 and Oct 2015, during the same period ATMs increased by around 43% while POS machines increased by around 28%. Another disconcerting feature is that the rate of growth in setting up card acceptance infrastructure has also slowed down during these three years. -

Additionally, the growth in the acceptance infrastructure has not been uniform across all locations in the country with higher concentration of such infrastructure noted in urban areas and larger towns and with larger merchants. Thus, the usage of cards has been constrained by lack of accessible acceptance infrastructure, especially in rural areas where the growth in card issuance has been very high in recent times. -

Debit cards usage is predominantly taking place at ATMs as compared to POS; as a result there are issues of costs and risks associated with cash management of ATMs. The usage of debit cards at ATMs account for nearly 90% of the overall debit card transactions in terms of volume and around 95% in terms of value. -

While almost every bank is a card issuer, very few banks are engaged in the activity of merchant acquiring and setting up of card acceptance infrastructure. Thus, there is concentration in acquiring business with the top 5 acquirer banks accounting (as at end-December 2015) for nearly 81% of the POS infrastructure and top 10 acquirers’ share of POS being above 90%. At the same time, the share of these banks in terms of their debit card issuance was around 41% (top 5 acquirer banks) and around 51% (top 10 acquirer banks). -

In terms of merchant establishments accepting card payments, the number has increased from 0.85 million merchant establishments in Oct 2013 to around 1.15 million establishments in Oct 2015, a growth rate of 34%. As on Dec 2015, the number of such merchant establishments was 1.26 million. This increase is largely driven by increasing share of public sector banks in merchant acquisition. However, due to multiple terminalisation of the same merchant by different banks, the actual number of unique merchant establishments could be quite lower. -

Based on inputs provided by card networks, it is understood that growth in debit card usage is largely witnessed in the CNP segment driven by e-commerce. 2.9 From the above, it can be noted that the while there has been significant growth in number of cards, the growth of infrastructure has been lower both numerically and in terms of geographic spread, and this has impacted the card usage. Cross-country comparison 2.10 Apart from the above observations in respect of the present status of card usage and acceptance in the country, a comparison with a few advanced countries as well as emerging economies also reveals that better penetration of infrastructure remains to be achieved. 2.11 As per the cross-country statistics in the Red Book3 the number of card payment transactions (including debit and credit cards at both ATM and POS) per inhabitant in India is 6.7, whereas the corresponding data for a few other countries reveal a much higher level of card usage – Australia (249.3), Canada (247.9), Korea (260.8), France (143.4), Sweden (270), United Kingdom (201.7), Brazil (54.8), China (14.4), Mexico (16.6), Russia (47), etc. Even in terms of available infrastructure, the comparative position as at end-2014 is as below: 2.12 Thus by any yardstick, there is no gainsaying the fact that the acceptance infrastructure has to be vastly improved in the country so that the benefits – both individual as well as macro-economic – of card payments accrue to the entire economy. What are the factors inhibiting growth in acceptance infrastructure? 2.13 The possible reasons for such poor growth in acceptance infrastructure are: -

High cost of acquiring business that include high capital cost of POS machine, recurring maintenance / servicing cost, difficulty of servicing POS machines in rural areas, etc. is a major constraint. -

Low utilization of cards makes acceptance for small merchants and / or in rural areas unviable due to low card footfalls and low transaction values besides other costs associated with merchant acquiring, ultimately forcing acquiring banks to withdraw the POS terminal. -

Lack of adequate and low cost telecommunication infrastructure makes it difficult for merchants to access networks which are required to accept electronic payments and process these transactions. Poor telecom connectivity in many areas lead to fewer transactions and consequently affect revenue of acquirers. -

Lack of incentive for merchants to accept card payments is another inhibiting factor. Further, transparency and audit trails associated with card payments often act as deterrent for accepting card payments by merchants. -

Insufficient awareness about the costs associated with use of cash and cash handling is also a contributing factor. -

Factors from consumer perspective, such as, low levels of awareness, apprehension of using non-cash payments, especially concerning its safety and security, anonymity associated with cash payments, surcharge / convenience fees being levied for use of card / electronic payments, difficulties in changing consumer behavior, etc. also inhibit growth / usage of card of payments for purchase of goods and services. -

Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) also often acts as a disincentive. Though the regulatory policy on MDR (issued in September 2012) had indicated a cap on MDR, it is generally treated as floor, with the benefit of lower MDR not really accruing to smaller merchants. In certain segments like mutual funds, insurance, etc. a flat fee structure of charges has also been established by the industry. 2.14 Hence, cash continues to be the predominant mode of payment as it appears to be “costless” in comparison to the visible costs associated with card / electronic payments. 2.15 In light of the above, the succeeding chapters outline the broad contours of a multi-pronged strategy to enhance the growth in acceptance infrastructure including further rationalisation of MDR or merchant fees. Chapter - 3

Strategies for enhancing acceptance infrastructure 3.1 Cards payments exhibit a high level of network effect, thus there needs to be a critical mass of both issuance and acceptance of such payments. Presence of a large card base loses significance if it is not coupled with adequate and accessible infrastructure. 3.2 There can be two broad types of strategies to ensure “managed” expansion of the acceptance infrastructure for card payments. The contours of these strategies are outlined below along with specific issues that need to be addressed in respect of each of the strategies. 3.3 While the first strategy indicated below seeks to address the concentration issue highlighted earlier in the acquiring business and increase the breadth of participants in the acquiring segment, the second strategy addresses the issue related to “economics” or cost elements involved in setting up the card acceptance infrastructure. Card payments necessitate infrastructure in terms of hardware, software and communication elements all of which involve both capital investment as well as recurring operational expenses. Hence, this strategy envisages the reduction in the cost for acquirers by subsidising some of the costs involved in acquiring business. Strategy 1: Mandate terminalisation to issuers in proportion to their card issuance 3.4 Prima facie this strategy mandating banks to install / acquire terminals in some proportion to the number of cards they have issued may seem to be the answer to all the problems. 3.5 After all, the cards issued by them are the ones that need to be used! Further, as it would be easy to obtain the data on number of cards issued, it would also be easier to monitor the implementation program of banks in setting up POS terminals / card acceptance infrastructure. 3.6 Although the above strategy may appear an easier option to expand the POS base, there are a few strong impediments to its implementation: -

Oftentimes cards are issued by the banks on account of some mandate; as a result, banks incur high costs associated with card issuance with low commensurate revenue on card usage (as card activation rate is very low) -

Not every bank is equipped to run merchant acquisition business; lack of expertise may lead to some banks entering this business through outsourcing model but very soon the poor economics of the business makes it unviable -

The basis for setting targets could be either on the total number of cards issued by banks or on the basis of actual usage of cards. If the targets are set on the basis of cards issued, then it would not take into account the levels of dormant / inactive cards, multiple cards issued to single account, etc. thereby adding to the cost burden of the issuers. On the other hand, if targets are set on the basis of card usage, then issues such as whether card usage at ATMs or usage only at POS is to be considered. Further, it also needs to be considered whether repetitive use of same cards or only unique card usage should be the basis. Thus, there would be difficulties in selecting the basis for setting targets for terminalisation. Strategy 2: Promote setting up of Acceptance Development Fund 3.7 The other strategy, which has also been successfully implemented in some countries, is the use of Acceptance Development Funds (ADFs). The ADFs are market-driven initiatives (sometimes with regulatory recognition) where different stakeholders in the card payment value chain come together to set up a program to encourage wider deployment of card acceptance infrastructure. 3.8 Typically, these ADFs are generally funded by card issuers to build a corpus by diverting a percentage of their transaction revenue into the fund which is then invested in structured initiatives to expand acceptance infrastructure in the country. ADFs are usually managed by third parties who establish the framework for use of funds which include subsidies for installation of terminals, development of new technologies / segments / geographies, marketing and education to increase awareness for acceptance as well as for usage. 3.9 The main objective of the ADF program is to subsidise the cost of acceptance infrastructure such that it enables banks to speed up their merchant acquiring activities and increase penetration in both existing market segments as well as new markets. Essentially, ADF functions as a financial pool which can be accessed to address some of the economic constraints associated with acquiring / setting up infrastructure to acquire card payments. This helps to reduce the stress on thin margins and also helps in reducing the payback period of investment for acquirers. 3.10 ADFs have been used successfully in some countries like Poland and Indonesia where the card payments ecosystem has seen a higher penetration of card acceptance, especially in newer market segments after the launch of the ADF. Recently Malaysia has also set up such a Market Development Fund to set up 800,000 new terminals by 2020. 3.11 In the interest of having a well-established ADF with in-built transparency in its functioning, it is important to establish ‘Operating Guidelines’ or ‘Standard Operating Procedure’ by addressing the following issues: (i) Organisation and management of the ADF – The ADF could be set up with active participation of all card payment networks authorised in the country to meet the objective of developing the acquiring infrastructure and ecosystem. There could be a governing council / body, drawn from banks and industry bodies, set up to manage the ADF as well as set the rules for deployment of resources. Oversight of the activities could be entrusted to any existing industry association (say, the Indian Banks Association) with suitable regulatory reporting mechanism in place. (ii) Source of funds / contribution to the ADF – Contributions to the fund should originate from the card issuers; card payment networks may also be co-investors to the fund. There could be different methods to determine the level of contribution - as a percentage of card spends or as a percentage of interchange revenue generated when cards are used. Usage of both debit as well as credit cards could be considered or only one type of card may be considered. Ideally, the contribution could be deducted at source during the settlement of interchange to the issuers by the card payment networks. Contribution based on card usage / spends at POS will ensure that issuers with large number of inactive cards are not unduly burdened with additional costs. The funds could be escrowed as determined by the ADF management. Perhaps, contribution from the Financial Inclusion Fund (FIF) could be also considered to give a boost to the sources available to the ADF particularly for setting up acceptance infrastructure in rural areas and hilly terrains. Similarly, certain resources from the Depositors’ Education and Awareness Fund could be also be used to contribute to the ADF to be specifically used for building awareness amongst customers. (iii) Validity period of the fund – The ADF could be set up with a fixed period within which a specific number of terminals need to be deployed or it could be an on-going process with yearly targets set for widening acceptance infrastructure. (iv) Parameters for application / utilisation of ADF resources – Eligible acquirers who deploy terminals / acquiring infrastructure can obtain resources from the ADF as per set parameters. These conditions or rules for availing grants or subsidies from the ADF would need to be determined taking into account the segments, merchants, channels and geographies which need to be prioritised for widening deployment and availability of infrastructure. Some of the parameters that could be considered include: -

Geographic segments – rural and semi-urban targets only, or include urban and metro areas too for specific merchant and market segments -

Market segments – healthcare, utilities, public distribution system, markets / kirana stores / convenience stores, and such other areas where non-discretionary or involuntary spends of day-to-day requirement occur; these are also areas where large volumes of small value transaction take place in significant proportion (presently undertaken in cash) -

Merchant segments – small merchants, big merchants, SMEs, etc. if focus is to be given to encouraging card acceptance by these entities; whether e-commerce segment should be considered also needs to be examined. -

Channel segments – depending on the geographies and the existing telecommunication infrastructure, focus could be on terminalisation using existing POS, contactless payments, mobile-based POS and so on so as to support new POS technologies and applications. -

Type of expenses to be covered – both capital and operating expenses or only either of them; marketing and education expenses, merchant training, etc. could be covered. -

Deployment locations – subsidy to be given only for new deployment of terminals or replacements also; unique merchant locations to be considered or additional terminalisation at merchants already terminalised also needs to be subsidised. -

Time of granting subsidy – immediately after deployment of terminal or after a certain agreed period during which time the activation / utilisation rate is monitored -

Amount and frequency of subsidy – subsidy to be given on monthly basis or a one-time grant; if given on monthly basis then the amount and duration need to be fixed (based on monitoring of progress in terminal utilisation) and taking into account the possibility of low frequency and volume of transactions in certain geographic segments. Further, the amount of subsidy could also vary depending upon the technology that is used (for instance, m-POS may be less cost intensive as compared to regular terminal). | Questions for public feedback Specific feedback with rationale and examples may be provided on the following: Q.1) Which strategy is preferable – mandate acquiring in proportion to card issuance or widening acceptance infrastructure through setting up of ADF? Q.2) If ADF is the chosen strategy, who could be entrusted with its management? Q.3) In case of ADF, who should contribute and at what levels? Q.4) What could be the specific parameters to determine the eligibility criteria for receiving grants from the ADF? Q.5) What could be an achievable target for POS expansion through ADF over a period of three to five years? Q.6) Any other workable strategy that could be considered. | Chapter - 4

Rationalisation of Merchant Discount Rate 4.1 As can be seen from the previous chapter, high cost of acquisition and poor revenue from the acquisition business is one of the most significant reasons for low growth in acceptance infrastructure. The major source of revenue in the card business is the Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) or Merchant Service Fee. MDR comprises other cost segments such as the interchange fee (fee paid by acquirer to card issuing bank), processing and other fees payable to the card network, and other costs incurred by the acquirer along with acquirer’s margin. While merchants feel that MDR is an inhibiter (to the exclusion of other possible reasons) for card acceptance acquirers too are of the opinion that thin margins on MDR often make their business unviable. 4.2 Hence, it is felt that the issue of MDR also needs to be addressed in the context of enhancing the acceptance infrastructure in the country. Therefore, taking into account the dynamics of this market and the economics underlying this activity, multiple options for rationalization of MDR for debit card transactions are outlined below. Certain advantages as well as disadvantages of these options are also indicated. Option 1: Uniform ad-valorem MDR across all merchant categories & locations 4.3 In order to encourage all categories of merchants to deploy card acceptance infrastructure and also to facilitate acceptance of small value transactions through debit card payments, the Reserve Bank had rationalized MDR by fixing a cap on the charges for debit card usage as under: - not exceeding 0.75% of the transaction amount for value upto Rs. 2000/-

- not exceeding 1% for transaction amount for value above Rs. 2000/-

4.4 The mandate was issued taking in to account the fact that debit card is a secured product with the card usage being linked to the availability of funds in the accounts of the customers. The move was expected to encourage small merchants to deploy POS terminals and also encourage them to accept small ticket size transactions. 4.5 The first option could be to retain status quo in the regulatory structure for MDR for debit cards. 4.6 However, as indicated earlier, the data reflects that the year-on-year growth of deployment of POS terminals has come down in recent years with lower MDR being cited as one of the reasons making this business unviable. 4.7 While having a uniform lower MDR across all merchant categories has the beneficial potential to encourage small merchants to accept card payments including for small ticket transactions, it also has the downside that larger merchants in the cities (who anyway have a better negotiating power) are the ones who stand to gain. This can drive down the revenue margins for acquirers, thus making the business unviable. Option 2: Differentiated MDR at select merchant categories at all locations 4.8 The other possible approach is to have a differentiated MDR framework for some select merchant categories across all locations. This approach may provide some scope to the acquiring banks to make their business viable and also help in increasing the infrastructure in segments which have the potential but have not shown encouraging growth. 4.9 Illustratively, the specific merchant categories could include those segments which constitute a bulk of non-discretionary spends by individuals on essential goods and services, such as, utility bill payments (electricity, water, gas, telephone), municipal taxes, primary hospitals and health centres, primary educational institutions, public distribution system outlets ( like ration shops), fertilizers, seeds and similar agricultural products, public transport, etc. 4.10 The potential benefits of this approach include the possibility that lower MDR would encourage merchant establishments of specific segments to accept card payments; uniform MDR for specific segments across the country would benefit even the urban population; and impact on stakeholder revenues would be relatively lower as they would have option to charge higher MDR for other segments, of course, within regulatory ceilings where applicable. 4.11 However, unless there are specific targets for deployment, this approach could lead to further expansion of acceptance infrastructure only in cities with higher card usage, and this may further skew the concentration around the cities and bigger towns. Option 3: Differentiated MDR at select merchant categories in Tier III to VI locations 4.12 The third alternative is to rationalise MDR in select categories in Tier III to VI locations with the objective of ensuring wider deployment of POS terminals in specific locations and also minimising the revenue impact on the industry. 4.13 Under this approach specific merchant categories which have regular footfalls of customers can be targeted in deeper geographies to ensure wider acceptance of card payments and also to move away from cash payments for these generally small ticket transactions. As the volume of transactions increase the economies of scale will reduce payback period (to the acquirer). 4.14 On the downside of this approach, the lower MDR coupled with logistics of deployment and maintenance and other related concerns of operating in deeper geographies may not encourage the acquirers to deploy POS terminals in these locations unless there is a specific mandate to do so. Option 4: Setting MDR for debit cards as a fixed / flat fee for transactions beyond a certain value 4.15 Prior to regulatory intervention / rationalisation of MDR in September 2012, the MDR for both debit and credit cards was the same. As debit card is a secured product wherein the card usage is directly linked to the availability of funds in the accounts of the customers, there is no direct credit risk involved in the processing of debit card transactions. Hence, it is often questioned as to why the concept of fixed fee per transaction cannot be considered for debit cards instead of the ad-valorem MDR presently charged. 4.16 However, the downside to this is that if the fixed fee is set too low across the board, it would make acquiring business unattractive, thus, defeating the very purpose of rationalising MDR. On the other hand, if set higher, the fixed / flat fee could be detrimental in adoption of card payments for low value payments and, particularly, by those segments of merchants operating on thin margins, which would make acceptance of card payments further unattractive. 4.17 Apart from this, stakeholders also often express concern that the suggestion of fixed fees does not take into account the fact that many of the costs associated with acquiring business (besides the capital and operational expenses for hardware, software, network and communication), such as, risk and fraud monitoring and underwriting thereof, merchant training and education, etc. continue to remain the same irrespective of whether it is a debit or a credit card. 4.18 Taking into account the above, the option of levying a flat / fixed fee as MDR for transactions above a certain threshold value can be considered. For transactions below this value, MDR at ad-valorem basis may continue. 4.19 As a variant of the above, it may also be possible to consider a combination structure of MDR for debit card consisting of a minimum flat / fixed fee plus an ad-valorem fee as MDR for transactions exceeding a specified threshold value. Other Issues 4.20 In addition to the above options which explore the different combination of specific merchant categories and specific locations, there are other issues which also merit some review or reconsideration in this regard. Some of these pertain to: Issue A: Whether there should be differentiated MDR for C2G payments? 4.21 Wider adoption of electronic payments in Customer-to-Government (C2G) segment would have a positive demonstration effect on other merchants too to accept electronic payment instruments. 4.22 A view is that the Government not being a commercial entity should not be charged MDR like other business entities. Presently, in some segments, these charges are borne by the customer in the form of convenience charge or surcharge levied for electronic transactions including card payments, and this comes in the way of higher adoption of card payments for C2G payments. 4.23 In the context of the Government’s declared intention of moving away from cash to promoting card transactions, there is a case for the Government bearing the cost, particularly given that it would reap the benefits of lower cash handling cost and transparency in its customer-facing transactions. 4.24 In light of the above, whether a differential MDR for C2G payment segments can be considered, at least for a few years? This would not only help in encouraging electronic payment habits in consumers but also facilitate speedier electronification of government receipts thus leading to reduction in cost incurred by Government in collection of its receipts through non-electronic channels. Issue B: Whether merchant charges should be unbundled? 4.25 Often times, merchants are charged a composite fee by acquiring banks by bundling or combining the charges for debit cards, credit cards, prepaid cards, international and domestic cards, depending upon the usage of such cards at the merchant location. This results in lack of transparency in arriving at the charges for specific cards at the merchant. It also makes it difficult to ensure adherence to the regulatory mandate on MDR for debit cards. 4.26 Further, where there are instances of surcharging, the merchants pass on these composite charges to the customers irrespective of the type of card used and the underlying differences in merchant charges. 4.27 Therefore, it is to be considered whether such distortions need to be addressed by way of a mandate to unbundle the MDR for each category of cards so as to reflect the right cost structure of transactions using respective type of card. Issue C: Whether MDR for credit cards should be rationalised? 4.28 As indicated earlier, the regulatory intervention in MDR was focused on debit cards taking into account the larger proliferation of such cards and the absence of direct credit risk in such cards. 4.29 However, taking into account the above feature of bundled charges to merchants, it is to be examined whether there is a need to rationalise MDR on credit card transactions as well. | Questions for public feedback Specific feedback with rationale and examples may be provided on the following: Q.1) Which of the above options would be most suited to meet the requirements of encouraging merchant acceptance of card payments while meeting acquirer viability requirements? Q.2) Which merchant categories could be considered for differentiated MDR under Option 2? Q.3) In case of Option 2, what could be the level of rationalised MDR? Q.4) Is there a case of fixed / flat fee for debit card transactions? If yes, should it be across the board or after a certain threshold? Q.5) Will a hybrid MDR structure of fixed upto a threshold amount and then ad-valorem charges beyond this threshold or the reverse should be considered? Q.6) What should be the MDR for C2G payments? Q.7) Whether merchant charges should be unbundled? Q.8) Is there a case of rationalising MDR for credit card transactions? Q.9) Any other combination or workable solution that can be considered. |

|