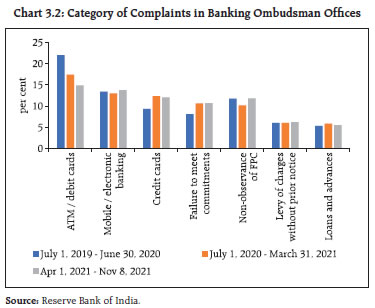

As economic activity charts an uneven and recently slowing path of recovery, global regulatory efforts focus on enhancing resilience of sectors which showed vulnerability during the pandemic. In India, the thrust of policy measures is to revive credit, widen investor bases in the G-Sec and securitisation markets and sharpen and harmonise the NBFC regulatory framework for focussed supervisory attention. The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) addressed fragilities of open-ended mutual funds through market-based mechanisms. The Insurance and Regulatory Development Authority of India’s (IRDAI) initiatives cover the governance of insurance companies and cyber and trade credit insurance. The Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority’s (PFRDA) focus was on expanding the coverage of the National Pension Scheme (NPS). The International Financial Services Centres Authority (IFSCA) continued to improve the regulatory framework for entities operating under it. The Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC) remained committed to enhancing the robustness and stability of the financial system. Introduction 3.1 An uneven economic rebound is losing steam against an inflation outlook clouded with upside risks. Transition challenges also include elevated levels of indebtedness across sovereigns, non-financial corporates and households, structural vulnerabilities in market-based finance structures, probability of higher insolvencies and credit losses when policy support is wound up and moral hazard from heightened expectations of more policy support. This chapter reviews regulatory initiatives globally and in India that are navigating this inflection point. III.1 Global Regulatory Developments and Assessments 3.2 Global regulatory institutions mobilised in three distinct forms. Firstly, considerable regulatory attention is being paid to distil the lessons from the pandemic. Secondly, efforts are being directed towards increasing resilience of sectors and market segments which have faced difficulties in coping with the dislocations caused by the pandemic. Thirdly, attention is also being paid to the financial stability implications of COVID-19 support measures and their withdrawal. III.1.1 Lessons from the Pandemic 3.3 According to the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the global financial system has shown resilience and endured the pandemic by virtue of swift policy responses1. Inadequacies have been observed in respect of capital and liquidity buffers as well as in the non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) sector. There are concerns about excessive procyclicality in the financial system, highlighted by asset market dislocation during the pandemic. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) and the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) have analysed the margining practices of central counterparties (CCPs) covering initial margins (IMs) and variation margins (VMs), including from the point of view of transparency, predictability, and volatility2. A broad based and rapid increase in margin calls across the financial system has been noted across asset classes, particularly with regard to CCPs while margining requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives remained stable during the period. The FSB is taking forward a comprehensive work programme to improve functionality of international financial standards, reduce vulnerability and pro-cyclicality to safeguard global financial stability and support an equitable recovery from the pandemic. 3.4 Central counterparties are highly interconnected with financial institutions and markets and, therefore, too important to fail. The increased volumes of trades being cleared through CCPs and their increasing global connectivity highlight the need for prudent management. In this regard, the size and composition of CCP liquidity buffers and the payment obligations of the CCP, if a clearing member defaults, is a pointer to the CCPs’ own estimate of the probability of such dislocation and the markets available to CCPs to meet their payment obligations. 3.5 The public disclosure templates put together by the CPMI and the IOSCO require CCPs to report the size and make-up of their qualifying liquid resources on a quarterly basis. It defines eight sources of liquidity for CCPs: central bank cash; secured cash at commercial banks; unsecured cash at commercial banks; secured credit lines; unsecured credit lines; highly marketable collateral; supplementary liquidity; and other resources. Aggregate liquidity buffers maintained by three large global CCPs {viz., the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), Eurex Exchange and London Clearing House (LCH)} have declined after a sharp rise during the pandemic (Chart 3.1). Though the gross pool of liquidity buffers may per se not reflect procyclicality, an analysis of the composition of such buffers reflects a surge in the proportion of cash deposits at central banks. The aggregate proportion of cash deposits with commercial and central banks rose to 80 per cent of the liquidity pool at the expense of highly marketable collateral held in custody, the share of which in the total liquidity pool dropped from 46 per cent in Q4:2019 to 17 per cent in Q2:2021. III.1.2 Systemic Resilience of Money Market Funds (MMFs) 3.6 The March 2020 market turmoil exposed vulnerabilities in money market funds (MMFs). The FSB has explored policy proposals to enhance resilience of MMFs to help address systemic risks and minimise the need for future extraordinary central bank interventions to support the sector3. The range of policy options to address MMF vulnerabilities include swing pricing imposed on redeeming fund investors; capital buffers to absorb credit losses; mechanisms to address regulatory thresholds that may give rise to cliff effects; and limits on eligible assets and additional liquidity requirements to reduce liquidity transformation. III.1.3 Pandemic Measures: Financial Stability Implications 3.7 The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) has noted the significant rise in gross European bank debt, partly due to guaranteed loans that have eased liquidity risks and reduced firm defaults and provisioning4. However, if loans with public guarantees mature and are renewed without public guarantee, risk weights will increase, and the level of provisioning might turn out to be lower than required. III.1.4 Other International Regulatory Developments A. Banks 3.8 The FSB has offered suggestions to harmonise cyber incident reporting5 to obviate (a) fragmentation across sectors and jurisdictions; (b) diversity in methodologies to measure its severity; and (c) variation in timeframes for reporting incidents and use of incident information. Greater convergence in reporting can be achieved by developing global best practices, identifying and understanding the difficulties in sharing common types of information across jurisdictions, and developing a taxonomy for cyber incident reporting with a common definition for ‘cyber incident’. 3.9 On the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) cessation, the FSB has emphasised the need for market participants to act urgently to ensure that they are fully prepared for transition by the end of this year, with certain key USD settings continuing until end-June 2023 to support the rundown of legacy contracts, executed before January 1, 20226. Continued reliance of global financial markets on LIBOR poses risks to global financial stability. The transition should be primarily to overnight risk-free rates (RFRs), the most robust benchmarks available, to avoid reintroducing the weaknesses of LIBOR. The FSB also underlines the need for potential alternative rates to reflect credible underlying markets underpinned by a sufficient volume of transactions. B. Asset Markets 3.10 In the context of the growing role and influence of environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings and data products providers in the financial markets responding to increased investor sensitivity to the potential financial risks posed by climate change and other ESG considerations, the IOSCO has recommended that regulators focus more attention on the use of ESG ratings and data products and the activities of the providers of such products and services7. It also recommends that the rating and data product providers should consider factors related to issuing high quality ratings and data products, including publicly disclosed data sources, defined methodologies, management of conflicts of interest, high levels of transparency and the handling of confidential information. Users of ESG ratings and data products could consider conducting due diligence on their usage in their internal processes. It also recommends improving information gathering processes, disclosures and communication between providers and entities subject to assessment. 3.11 The IOSCO has provided guidance to support its members in regulating and supervising the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) by market intermediaries and asset managers, in view of its potential to create or amplify certain risks which can undermine financial market efficiency and consumer protection8. Regulators should a) consider stipulating that designated senior management should be made responsible for the oversight of AI and ML development, testing, deployment, monitoring and controls; (b) require firms to have adequate skills to develop the AI and ML as per needs and oversee controls; (c) stipulate oversight and monitoring of the performance of third party service providers; and (d) require firms to disclose meaningful information to customers around their use of AI and ML that impact client outcomes. C. Crypto Currencies – Stablecoins 3.12 The President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) set up by the US Treasury9 acknowledged the rise of market capitalisation of stablecoins and outlined recommendations to protect against prudential risks. Stablecoins are digital assets that are designed to maintain a stable value relative to a national currency or other reference assets. They are predominantly used in the United States to facilitate trading, lending and borrowing of other digital assets. The market capitalisation of stablecoins issued by the largest stablecoin issuers exceeded $127 billion as of October 2021, a nearly 500 per cent increase over the preceding twelve months. The report states that if well-designed and appropriately regulated, stablecoins could support faster, more efficient, and more inclusive payments options. However, it raises concerns related to the potential for destabilising runs, disruptions in the payment system and concentration of economic power. It also highlights that stablecoins pose anti-money laundering (AML) / combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) risks, thereby raising concerns for market integrity and investor protection. It has recommended legislative changes to address the gaps in the authority of regulators to reduce these risks. D. Climate Risk 3.13 The International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) analysed the impact of climate change on the asset side exposures of the insurance sector, based on data covering 75 per cent of the global insurance market10. It finds that more than 35 per cent of insurers’ investment assets, including equities and corporate debt, loans and mortgages, sovereign bonds and real estate could be exposed to climate risks, with housing and energy-intensive sectors accounting for the major share. The recommendations for insurers include (a) incorporation of climate related risk in insurers’ own risk and solvency assessment; (b) assessment of the impact of physical and transition risk on their investment portfolio and asset liability management; and (c) disclosure of material risks. 3.14 The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) has highlighted that central banks and supervisors may increasingly be exposed to the risk of climate-related litigation involving substantial financial implications11. Financial institutions may increasingly face claims relating to disclosures for green financial products and potentially breach-of-contract claims relating to such products as well as breaches of fiduciary duties if, for instance, they decide to continue to finance polluting projects. Accordingly, supervisors need to ensure that their supervised entities adequately manage financial and operational risks resulting from potential climate-related litigation against themselves as well as against institutions to which they are exposed. III.2 Domestic Regulatory Developments 3.15 During the period since July 2021, the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC) chaired by the Union Finance Minister met once on September 3, 2021. The meeting deliberated on the various mandates of the FSDC, viz., financial stability; financial sector development; inter-regulatory coordination; financial literacy; financial inclusion; and macro prudential supervision of the economy, including the functioning of large financial conglomerates. The Council, inter alia, discussed issues relating to management of stressed assets, strengthening institutional mechanisms for financial stability analysis, financial inclusion, framework for resolution of financial institutions and issues related to IBC processes, banks’ exposure to various sectors, data sharing mechanisms of government authorities, internationalisation of the Indian Rupee and pension sector related issues. The Council also took note of the activities undertaken by the FSDC Sub-Committee chaired by the Governor, Reserve Bank and the action taken by members on the past decisions of the FSDC. III.3 Initiatives from Regulators/Authorities 3.16 Financial sector regulators launched several initiatives for the development of the financial system and enhancement of its robustness and resilience (Annex 3). III.3.1 Transfer of Loan Exposures 3.17 The Reserve Bank issued directions governing transfer of loan exposures, both stressed and those not in default, in September 2021, harmonising the extant guidelines on such transfers and making them consistent with the current paradigm on resolution of stressed assets. 3.18 In terms of the directions in case of loans in default, transfer can be effected only through assignment or novation. While commercial banks, non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), all India financial institutions (AIFIs) and asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) have general permission to be transferees, specific permission has been given for transfer to any entity12 permitted to hold loan exposures in terms of a statutory provision or under the regulations issued by a financial sector regulator, including corporates. The Swiss Challenge method has been made mandatory for price discovery where the aggregate exposure of all lenders is not less than ₹100 crore as well as in cases of transfer of loan exposures undertaken as a resolution plan under the prudential framework. ARCs have been permitted to acquire loans where frauds have been detected, on the lines of banks and NBFCs, so as to provide a level playing field, subject to all operational responsibilities related to frauds being transferred to them. 3.19 As regards loans not in default, the directions restrict transfer of loans by lending institutions regulated by the Reserve Bank to scheduled commercial banks (SCBs), NBFCs and AIFIs, with the permitted routes being through assignment, novation or loan participation. Transfers under loan syndications have also been brought under the ambit of the directions. The requirement of minimum holding period (MHP) for transfer of loans has been simplified. III.3.2 Securitisation of Standard Assets 3.20 The Reserve Bank issued revised guidelines on securitisation of standard assets in September 2021, with a view to aligning the regulatory framework with Basel III guidelines and developing a robust securitisation market while incentivising simpler securitisation structures. The directions permit only those securitisation transactions which are traditional securitisations i.e., securities issued by a special purpose entity (SPE) where the cash flows are from a specified pool of underlying loans acquired from a lender. The Minimum Holding Period (MHP) and Minimum Retention Requirement (MRR) conditions have been simplified in line with the Master Direction on Transfer of Loan Exposures. The revisions also include permission for single asset securitisation, simplified instructions governing reset of credit enhancements, concessional capital regime in case of simple, transparent and comparable (STC) securitisations and capital framework in line with the Basel III norms. III.3.3 Credit Risk Mitigation (CRM) for Derivative Transactions of Foreign Bank Branches 3.21 A Credit Risk Mitigation (CRM) mechanism was put in place through guidelines issued in September 2021 whereby the gross exposure of foreign bank branches in India to their head office (HO) [including overseas branches] can be offset by CRM while reckoning Large Exposure Framework (LEF) limits. The CRM will comprise of cash / unencumbered approved securities the sources of which should be interest-free funds from HOs or remittable surplus retained in the Indian books (reserves) held with the Reserve Bank13. As part of the grandfathering arrangement, foreign bank branches are permitted to exclude all derivative contracts executed prior to April 1, 2019 while computing derivative exposure on the HO / overseas branches. III.3.4 Scale Based Regulation for NBFCs 3.22 The regulatory framework for NBFCs was revised in October 2021 to introduce scale-based regulation. Under the new framework, NBFCs are placed in four layers, based on their size, activity, and perceived riskiness, viz., Base Layer (BL), Middle Layer (ML), Upper Layer (UL) and a possible Top Layer (TL). The regulations are progressively tighter for the higher layers. Regulations for NBFCs in the Base Layer (NBFC-BL) are broadly in line with extant regulations for non-deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-ND), except for changes in governance and prudential guidelines. NBFCs in the Middle Layer (NBFC-ML) will be regulated on the lines of systemically important non-deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-ND-SI), deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-D), core investment companies (CICs), standalone primary dealers (SPDs) and housing finance companies (HFCs), as the case may be, except for changes in capital, prudential and governance guidelines. NBFCs lying in the Upper Layer (NBFC-UL) are subject to regulations applicable to NBFCs in the Middle Layer (NBFC-ML) with additions such as introduction of common equity tier 1 and leverage requirements, mandatory listing, qualification of board members and the like. For NBFCs falling in the Top Layer (ideally vacant), while no specific regulation has been provided, they will, inter alia, be subjected to higher capital charges and enhanced supervisory engagement. III.3.5 Opening of Current Accounts by Banks 3.23 In order to instil credit discipline and prevent diversion of funds, the Reserve Bank had issued revised instructions in August 2020, introducing restrictions on opening of current accounts and cash credit (CC) / overdraft (OD) facilities by banks. With a view to ensuring non-disruptive compliance with the spirit of the regulations, the guidelines were revised on October 29, 2021 permitting (a) borrowers where the aggregate exposure of the banking system is less than ₹5 crore, to open current accounts and CC/OD accounts without any restrictions; and (b) borrowers availing CC/OD facilities to maintain current accounts with any one of the banks with which they have CC/OD facility, provided it has at least 10 per cent of the exposure of the banking system to that borrower; and to maintain collection accounts with other lending banks. Specified current accounts are exempted from the purview of the instructions. III.3.6 Retail Direct Scheme 3.24 The Reserve Bank launched the RBI Retail Direct Scheme (RBI-RD) in November 2021 which allows individual investors to open a Retail Direct Gilt (RDG) Account with the Reserve Bank using an online portal to facilitate investing in G-Secs in the primary and secondary markets. By providing a safe, simple, direct and secured platform, the Scheme aims to ease the access of G-Sec market to retail investors. III.3.7 Customer Protection 3.25 In the wake of the pandemic and the increased convenience of online transactions, financial transactions through the digital mode grew manifold. Concomitantly, complaints related to electronic and digital banking transactions viz., ATM/debit cards, credit cards and mobile/electronic banking collectively witnessed a spurt and comprised more than 40 per cent of the total complaints received in Ombudsman offices (Chart 3.2). Complaints related to ATM/debit cards alone, however, declined as compared to the previous two years reflecting proactive measures undertaken by the Reserve Bank and the service providers. III.3.8 Integrated Ombudsman Scheme, 2021 3.26 The Reserve Bank - Integrated Ombudsman Scheme (RBI-OS) for providing cost free redress of customer complaints involving deficiency in services rendered by entities regulated by the Reserve Bank was launched in November 2021. The new scheme integrates the three existing ombudsman schemes pertaining to banking (launched in 2006), non-banking financial companies (introduced in 2018) and system participants14 (notified in 2019). The Scheme, which has also been extended to cover non-scheduled primary urban co-operative banks with a deposit size of ₹50 crore and above, adopts a ‘One Nation One Ombudsman’ approach by making the redressal mechanism jurisdiction neutral. III.3.9 Default Fund (DF) of CCIL 3.27 The Clearing Corporation of India Limited (CCIL) maintains prefunded default handling resources as a CCP for each of its clearing services that could be accessed if the losses on a defaulting member’s portfolio exceed the resources made available by that member. These resources are maintained in excess of Cover-1 and Cover-2 stress loss15. They are funded by members’ contributions as well as by the CCIL’s own funds termed as Skin-In-The-Game (SITG) allocated from its Settlement Reserve Fund (SRF). CCIL’s SITG corresponding to each clearing service default waterfall is computed as the higher of 25 per cent of the respective member’s default fund or the highest contribution from a single member, subject to availability of resources in the SRF. The total default fund for each clearing service, comprising member contributions and the respective SITGs, is generally 125 per cent of Cover-1 / Cover-2 stress loss (along with stress loss of five weak entities). The default fund is revised on an intra-month basis in case stress loss (as per the segment’s cover) exceeds a specific threshold.  3.28 Prior to October 2021, the methodology used by CCIL for the intra-month revision could have resulted in total prefunded resources going below 125 per cent of the Cover-1 / Cover-2 stress loss. From October 2021, as advised by the Reserve Bank, the CCIL has modified the methodology to ensure that the total prefunded resources are 125 per cent of Cover-1 / Cover-2 stress loss by increasing members’ contributions even beyond 100 per cent, if required, in case the CCIL’s SITG goes below 25 per cent of Cover-1 / Cover-2 stress loss due to shortfall in the SRF. The CCIL makes annual additions to the SRF, based on its estimate of resources required. The SRF balance stood at ₹1,750 crore as on March 31, 2021. The CCIL’s SITG as a proportion to members’ default fund contribution is much higher than most other global CCPs (Table 3.1). 3.29 The modified framework is expected to enhance financial stability and considering the systemic importance of financial market infrastructures like the CCIL, this will improve the resilience of the financial ecosystem. III.3.10 Fintech 3.30 Fintech has accelerated transformation in the financial sector. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) defines Fintech as “technologically enabled financial innovation that could result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on financial markets and institutions and the provision of financial services”. India is amongst the fastest growing fintech markets in the world. A recent survey indicates that 87 per cent of the digitally active population has adopted fintech, placing it as a leader in the world16. Several factors have contributed to the spectacular growth of fintech in India. They range from copious funding by venture capital, private equity and institutional investors driving innovation; increasing telecom, internet and smartphone penetration; favourable demographics17; and the emergence of the IndiaStack - a set of open APIs [e-KYC, e-Sign, DigiLocker, and Unified Payments Interface (UPI)] that allows governments, businesses, startups and developers to utilise digital infrastructure The Reserve Bank’s calibrated regulatory approach has kept pace with the rapid developments in the fintech space (Box 3.1). III.3.11 Enforcement 3.31 During the period July-November 2021, the Reserve Bank undertook enforcement action against 90 regulated entities (seven public sector banks, ten private sector banks, 64 co-operative banks, three foreign banks, one small finance bank and five non-bank finance companies) and imposed an aggregate penalty of ₹35.63 crore for non-compliance with / contravention of statutory provisions and directions issued by the Reserve Bank from time to time. | Table 3.1: SITG Ratios for selected CCPs | | Sr. No. | CCP Name | SITG/DF Ratio* (per cent) | | 1 | LCH SA | 0.65 | | 2 | LCH | 1.01 | | 3 | OCC | 1.36 | | 4 | Eurex Clearing | 2.61 | | 5 | CME | 3.33 | | 6 | NASDAQ | 10.87 | | 7 | Shanghai Clearing House | 28.59 | | 8 | SGX DC | 41.75 | *In cases where resources are segregated by CCP at clearing service level or by currency, the resources are aggregated for determining the ratio.

Source: CCIL, CCP’s Public Quantitative disclosures |

Box 3.1: Fintech Regulation in India – The Evolving Landscape The Reserve Bank recognised the need for an enabling regulatory and supervisory framework to ensure orderly development of the fintech sector and address the associated issues such as financial stability, customer protection, cyber security and data protection as early as 2018 when a broad roadmap to leverage on the developments in fintech space was laid down in the Report of the Working Group on Fintech and Digital Banking. 2. The policy response to fintech so far has involved the following approaches, viz., (i) applying existing regulatory frameworks to new innovations and their business models, often by focusing on the underlying economic function rather than the entity; (ii) adjusting existing regulatory frameworks to accommodate new entrants and the re-engineering of existing processes to allow adoption of new technologies; and (iii) creating new regulatory frameworks or regulations to include (or prohibit) fintech activities. 3. As fintech adoption picked up in the country, the Reserve Bank issued regulations/ guidelines for emerging areas such as payments banks (2014), account aggregators (2016), mobile wallets (2017), pre-paid instruments (2017), peer-to-peer (P2P) lending (2017) and invoice based lending (Trade Receivable and Discounting System-TReDS) (2018). The regulations span requirements on legal form, ownership and group structure, initial capital, fit and proper criteria for directors and senior management, prudential requirements on capital, liquidity, leverage, governance and risk management, cyber-security and disclosure, market conduct and data protection, grievance redressal mechanism and AML / CFT. 4. The Reserve Bank introduced a Regulatory Sandbox (RS) in 2019 to foster responsible innovation in financial services, promote efficiency and expand benefits to consumers. The first cohort on the theme ‘Retail Payment’ successfully tested products that can potentially revolutionise the digital payment landscape by using feature phone and offline payments. The second cohort on ‘Cross Border Payments’ is in progress and aims to address challenges of high cost, low speed, limited access and insufficient transparency in cross border payments. The third cohort on ‘MSME Lending’ envisages improved access to finance for micro, small and medium sized enterprises. The Reserve Bank has also set up the RBI Innovation Hub (RBIH), which is working towards creating an eco-system for idea generation and development through collaboration with tech innovators and academia for promoting access to financial markets and financial inclusion. The Hub would also develop internal infrastructure to promote fintech research. 5. Digitalisation of financial services can also bring in its wake various risks such as greater reliance on third-party service providers, mis-selling of financial products, breach of data privacy, unethical business conduct and illegitimate operations. The regulatory landscape for fintech is evolving to address such risks. The recently released report of the Working Group on Digital Lending is a pointer in this direction, through its thrust on enhancing customer protection and making the digital lending ecosystem safe and sound while encouraging innovation. 6. With a view to further channelising the potential of the country in fintech while managing attendant risks and ensuring effective regulation and supervision of entities, products and services, the Reserve Bank is currently in the process of consolidating all fintech related work under one umbrella. The new set up will be tasked with managing the entire gamut of fintech related activity in co-ordination with its regulatory and supervisory departments. | III.3.12 Swing Pricing Framework for Mutual Fund Schemes 3.32 With a view to ensuring fairness in treatment of incoming, existing and outgoing investors in mutual fund schemes, particularly during market dislocation, the SEBI introduced a swing pricing framework, which shall be effective from March 1, 2022, for open ended mutual fund schemes (with specified exceptions) for scenarios related to net outflows from the schemes. It provides for an optional partial swing during normal times and a mandatory full swing during periods of market dislocation for high-risk open-ended debt schemes. When swing pricing is triggered, net asset value (NAV) for incoming and outgoing investors is adjusted for the swing factor. III.4 Other Developments III.4.1 Deposit Insurance 3.33 The Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) Act, 1961 was amended in August 2021 to provide for time bound payment (interim) of deposits to depositors up to the amount insured in the case of banks with restrictions on withdrawal of deposits imposed by the Reserve Bank. In terms of the amendment which came into effect from September 1, 2021 the insured bank is required to submit its claim within 45 days of imposition of such restrictions and the Corporation has to get the claims verified within 30 days and pay the depositors within the next 15 days. The amendment empowers the DICGC to make interim deposit insurance pay-outs to troubled banks, even if they are under the Reserve Bank’s All Inclusive Directions (AID), within 90 days of imposition of such directions. In case the Reserve Bank finds it expedient to bring the bank under a scheme of amalgamation/compromise or arrangement/reconstruction, the liability of the Corporation will get extended by a further period of 90 days. The other amendments include raising the limit of 15 paise per ₹100 of deposits on insurance premium with the approval of the Reserve Bank of India. Furthermore, the DICGC, with the approval of its Board, may defer or vary the repayment period for the insured bank to discharge its liability to DICGC and charge penal interest of 2 per cent over the repo rate in case of delay. Consequent to these amendments, regulations on the procedure relating to claims settlement and granting time to insured banks for recovery of claims have also been amended. As of December 20, 2021, DICGC has paid ₹1,374 crore in respect of 1.09 lakh depositors of 16 out of 21 troubled banks that were eligible to receive such pay-outs. 3.34 The number of registered insured banks as on September 30, 2021 stood at 2,049 comprising 140 commercial banks (including 43 RRBs, two LABs, six payment banks and 11 small finance banks) and 1,909 co-operative banks. With the present limit of deposit insurance at ₹5 lakh, 98.1 per cent of the total deposit accounts, amounting to 267.2 crore, and 49.0 per cent, amounting to ₹78.02 lakh crore, of the total assessable deposits are fully protected. 3.35 During H1:2021-22, deposit insurance premium of ₹9,561 crore was collected, of which 93.5 per cent was contributed by commercial banks and the rest by co-operative banks. The settlement and recovery of claims from banks in H1: 2021-22 was significantly higher than a year ago. The Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF), built out of the premia paid by insured banks and coupon income received on investments in G-Secs, stood at ₹1.41 lakh crore, yielding a reserve ratio (ratio of DIF to insured deposits) of 1.81 per cent (Tables 3.2 to 3.4). | Table 3.2: Claims Settled and Recovery of Claims | | (in ₹ crore) | | Period | Claims Settled | Recovery of Claims | | 2021-22 (H1) | 393 | 267 | | 2020-21 (H1) | 27.4 | 33.7 | | Source: Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC). |

| Table 3.3: Deposit Insurance Premium | | (in ₹ crore) | | Period | Commercial Banks | Co-operative Banks | | 2021-22 (H1) | 8,939.1 | 621.6 | | Source: Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) |

| Table 3.4: Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) | | (in ₹ crore) | | As on | Deposit Insurance Fund | Reserve Ratio (per cent) | | September 30, 2021 | 1,40,831 | 1.81 | | March 31, 2021 | 1,29,904 | 1.70 | | Source: Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC). | III.4.2 Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process 3.36 Since the inception of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code in December 2016, 4708 CIRPs have commenced (as on September 30, 2021), of which 65 per cent have been closed. Of these, 23 per cent were closed on appeal or review or settled, 17 per cent were withdrawn, 46 per cent ended in orders for liquidation and 14 per cent culminated in approval of resolution plans (Table 3.5). 3.37 In case of the 421 CIRPs which ended in resolution, financial creditors (FCs) realised 36 per cent of their claims and 167 per cent of the liquidation value (Table 3.6). | Table 3.5: Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process | | (Number) | | Year / Quarter | CIRPs at the beginning of the Period | Admitted | Closure by | CIRPs at the end of the Period | | Appeal/ Review/ Settled | Withdrawal under Section 12A | Approval of Resolution Plan | Commencement of Liquidation | | 2016-17 | 0 | 37 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | | 2017-18 | 36 | 706 | 94 | 0 | 20 | 91 | 537 | | 2018-19 | 537 | 1157 | 153 | 97 | 79 | 306 | 1059 | | 2019-20 | 1059 | 1986 | 343 | 216 | 139 | 542 | 1805 | | 2020-21 | 1805 | 537 | 83 | 157 | 122 | 349 | 1631 | | Apr-Jun, 2021 | 1631 | 141 | 9 | 33 | 45 | 74 | 1611 | | Jul-Sep, 2021 | 1611 | 144 | 18 | 24 | 16 | 57 | 1640 | | Total | NA | 4708 | 701 | 527 | 421 | 1419 | 1640 | Note: 1. These CIRPs are in respect of 4593 CDs.

2. This excludes 1 CD which has moved directly from BIFR to resolution.

3. This Includes Dewan Housing Finance Corporation Limited data, the application filed by Reserve Bank was admitted under section 227 read with Financial Service Provider Rules of the Code.

Source: Compilation from website of the NCLT and filing by IPs. |

| Table 3.6: Outcome of CIRPs initiated Stakeholder-wise, as on September 30, 2021 | | Outcome | Description | CIRPs initiated by | | Financial Creditor | Operational Creditor | Corporate Debtor | Total | | Status of CIRPs | Closure by Appeal/Review/Settled | 189 | 507 | 5 | 701 | | Closure by Withdrawal u/s 12A | 152 | 368 | 7 | 527 | | Closure by Approval of Resolution Plan# | 241 | 135 | 44 | 420 | | Closure by Commencement of Liquidation | 628 | 628 | 163 | 1419 | | Ongoing | 809 | 759 | 72 | 1640 | | Total | 2019 | 2397 | 291 | 4707 | | CIRPs yielding Resolution Plans | Realisation by FCs as per cent of Liquidation Value | 181.5 | 115.2 | 140.8 | 166.6 | | Realisation by FCs as per cent of their Claims | 38.5 | 17.2 | 25.5 | 35.9 | | Average time taken for Closure of CIRP | 499 | 484 | 503 | 495 | | CIRPs yielding Liquidations | Liquidation Value as per cent of Claims | 6.3 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 7.1 | | Average time taken for Closure of CIRP | 395 | 364 | 341 | 375 | Note: # - This excludes Dewan Housing Finance Corporation Limited data, the application filed by Reserve Bank was admitted under section 227 read with FSP rules, of the Code.

Source: Compilation from website of the NCLT and filing by Insolvency Professionals |

| Table 3.7: Growth in SIPs (FY:2021-22) | | Particulars | Existing at the beginning of 2021-22 (Excluding STP) | Registered during 2021-22 | Matured during 2021-22 | Terminated prematurely during 2021-22 | Closing no. of SIPs at the end of Oct 31, 2021 | AUM at the beginning 2021-22 | AUM at the end of Oct 31, 2021 | | (in ₹ lakhs) | (in ₹ crore) | | SIPs | 368 | 137 | 13 | 33 | 458 | 4,24,817 | 5,49,518 | | Source: Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). | III.4.3 Mutual Funds 3.38 The asset base of the MF industry exhibited robust sequential growth for the last five consecutive quarters and stood at ₹37,33,204 crore at the end of October 2021, an increase of 32 per cent y-o-y. 3.39 Investments in MFs through systematic investment plans (SIPs) saw a significant leap both in terms of the number of SIPs added during the period April-October 2021 and in AUM (Table 3.7). III.4.4 Commodity Derivatives 3.40 As on December 21, 2021, the benchmark domestic commodity derivative indices, MCX iCOMDEX composite and Nkrishi index, rose by 12.5 per cent and 27.3 per cent respectively, over March 2021 closing, reflecting strong demand (Chart 3.3). 3.41 Driven by the increase in crude oil and natural gas prices, the iCOMDEX energy index moved up by 27.0 per cent during the period, while the iCOMDEX base metal index surged by 23.8 per cent over March 2021. In comparison, the iCOMDEX bullion index rose more tepidly, reflecting plateauing investor sentiment in the wake of rise in interest rates and strengthening of the U.S. dollar (Chart 3.4). 3.42 The aggregate turnover in commodity derivatives (across all exchanges) increased by 7.6 per cent over the corresponding period of the previous year, with energy derivatives being the driving factor (Table 3.8 and Chart 3.5).

| Table 3.8: Segment-wise Aggregate Turnover (Futures + Options) | | (₹ crore) | | FY Period/Turnover | Agri. | Bullion | Energy | Metals | Gems & Stones | Total Turnover | | 2020-21 (Apr-Nov) | 2,33,199 | 36,51,498 | 11,92,105 | 9,74,567 | 554 | 60,51,924 | | 2021-22(Apr-Nov) | 4,44,235 | 26,31,306 | 23,56,489 | 10,77,780 | 0 | 65,09,810 | | Change (per cent) | 90.5 | -27.9 | 97.7 | 10.6 | -100.0 | 7.6 | | Share (per cent) in 2021-22 | 6.8 | 40.4 | 36.2 | 16.6 | 0.0 | - | Note: Turnover includes Futures + Option turnover wherein Option Turnover is based on Notional value.

Turnover of Index Futures at MCX and NCDEX added in the respective sector.

Source: MCX, NCDEX, BSE, National Stock Exchange (NSE), Indian Commodity Exchange Ltd. (ICEX) |

III.4.5 Corporate Bond Market 3.43 The total capital raised in primary markets during the period April - November 2021 through equity [mainly qualified institutional placements (QIPs) and rights issues] and debt issuances stood at ₹5.5 lakh crore (Chart 3.6). 3.44 Issuances of listed NCDs at nearly ₹3.5 lakh crore were 22 per cent lower than those in the corresponding period last year. Conversely, CP issuances by corporates grew by 39 per cent over the same period. Highly rated instruments dominated the issuances (Charts 3.7 and 3.8).

3.45 The major issuers of corporate bonds were NBFCs and PSUs, accounting for 59 per cent of outstanding corporate bonds as on September 30, 2021 (Chart 3.9 a) whereas qualified institutional buyers (QIBs), body corporates and mutual funds were their major subscribers (Chart 3.9 b). III.4.6 Credit Ratings 3.46 A quarterly analysis of the credit ratings of debt issues of listed companies by major credit rating agencies (CRAs) between Q4:2019-20 and Q2:2021-22 shows that on an aggregate basis, there has been a fall in the share of downgraded issues in general (Chart 3.10). 3.47 Rating downgrades (23 issuers) during the period April-September 2021 spanned across sectors, with NBFCs and HFCs accounting for the major share during Q2:2021-22 (Chart 3.11).

III.4.7 Insurance 3.48 As of September 2021, the life insurance industry recorded growth of 5.82 per cent in new business premium (Chart 3.12). The total premium, which includes renewal premium, also recovered after a dip (Chart 3.13). 3.49 During the period April 2020 - September 2021, the life insurance industry received 1.38 lakh claims aggregating to ₹13,347 crore for COVID related deaths. Of these, 1.29 lakh death claims amounting to ₹11,059 crore were settled. The claim paid ratio in the above cases stood at 94.7 per cent in number and 84.7 per cent in amount. III.4.8 Pension Funds 3.50 As on November 30, 2021, the National Pension System (NPS) and the Atal Pension Yojana (APY) recorded growth of 22.5 per cent y-o-y in number of subscribers and 29.1 per cent in the corpus (Charts 3.14 and 3.15).

Summary and Outlook 3.51 The pandemic tested financial sector resilience in unparalleled ways. The financial system has, however, emerged healthier than was the case after the global financial crisis. As the economic outlook remains clouded, the global regulatory regime, which was on a pause mode with regards to ushering in more robust architecture, is putting the process back on course. Significant regulatory and supervisory attention to understand the layered impact of climate change on the economy and financial sector is also an ongoing endeavour. 3.52 Domestically, efforts to develop the regulatory architecture to increase resilience of the financial sector continue apace. The resilience of open-ended mutual funds, managing debt overhangs in the non-financial corporate sector and management of stressed assets remain policy priorities going forward. The new area of sustainable finance is also receiving due importance.

|