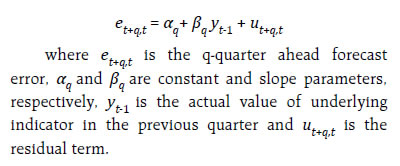

This article presents an analysis of annual and quarterly forecasts of major macroeconomic variables in the Reserve Bank’s bimonthly survey of professional forecasters (SPF). Forecast of output growth and CPI inflation for 2018-19 and 2019-20 was revised down. The forecast path of exclusion based CPI inflation was gradually revised up for 2018-19 but lowered for 2019-20. Forecast performance improves with reduction in forecast horizon, indicating forecasters’ tendency to update their forecasts with incoming information and provide more accurate estimates as they approach closer to the final estimate of the underlying indicator. The forecasts are found efficient for headline CPI inflation and exclusion based CPI inflation. Disagreement measures for GVA growth have remained close to its medium term average for all the forecast horizons in the recent period. The general behaviour of the inflation uncertainty largely shows that uncertainty moderated since November 2018. Introduction Economic agents have to often form expectations about the future trajectory of an economy to be able to take rational economic decisions, with complete prior knowledge, though the future is uncertain and the actual evolution of the economy may deviate from their expectations. For the conduct of monetary policy, given the challenges of long and variable lags in transmission, aggregated information on expectations of economic agents about the key economic parameters can be a useful input for setting the near to medium-term outlook for the economy. Unlike other forward looking surveys conducted by the Reserve Bank that collect information on expectations of households and firms, the survey of professional forecasters directly collects forecasts of key macro-economic parameters. Since professional forecasters generally monitor multiple domestic and global parameters, it is perceived that they can give forward looking views with better precision. The Reserve Bank has been conducting its survey of professional forecasters since the second quarter of 2007-08. The SPF panellists are drawn from both financial and non-financial institutions, which have established research set up and bring out regular updates on the Indian economy. Initially, the survey was conducted at a quarterly frequency, which was changed to bi-monthly in 2014-15 (28th round) after the change was introduced in the periodicity of the monetary policy review cycle. The survey questionnaire has broadly retained its character on major parameters, but certain modifications were incorporated to meet the evolving requirements. In every bi-monthly round, the survey collects annual quantitative forecasts for two financial years (current year and next year) and quarterly forecasts for five quarters (current quarter and the next four quarters). It covers 25 macroeconomic indicators including national accounts aggregates, inflation, money and banking, public finance and external sector. The survey solicits expectations of inflation, in terms of consumer price index (CPI) and wholesale price index (WPI), and economic growth, in terms of gross value added (GVA) and gross domestic product (GDP). The results are summarised in terms of the median of the responses received from the SPF panellists. The survey questionnaire also includes questions on the estimate of probability distribution of annual output growth for two financial years (current and next year) and quarterly inflation based on the consumer price index - combined (for four quarters ahead). For these density forecasts, respondents are asked to provide a probability distribution of forecast outcomes along a given set of intervals for each macroeconomic variable (viz., output growth and inflation). The estimated probability distribution helps to assess the extent of uncertainty in their forecasts. This article presents an analysis of SPF responses received since March 2018, when the number of survey responses ranged from 25 to 32 in different rounds of the survey. Section II presents a brief review of similar surveys conducted by other central banks. Section III discusses revisions in median forecasts of major macroeconomic indicators for the years 2018-19 and 2019-20 over successive rounds. Section IV evaluates the forecast performance while measures of uncertainty and disagreement are presented in Section V. Section VI sets out concluding observations. II. Review of Similar Surveys Conducted by Other Central Banks In the United States of America, the American Statistical Association (ASA) and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) jointly conducted the first quarterly SPF for the US economy in 1968. Subsequently it is being continued by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia since 1990. The survey collects comprehensive forecasts of economic and financial market indicators for both short and longterm1. The point forecasts include forecasts of output growth, non-farm payroll employment, unemployment rate, yield on government bills/bonds, corporate bond yields, corporate profits, private sector housing starts, inflation, etc. Besides these point forecasts, the survey also collects information on mean probability of unemployment rate, real output growth and inflation. The European Central Bank (ECB) has been conducting their quarterly SPF since 1999. It collects point forecasts and mean probability of real GDP growth, unemployment rate and inflation rate, both headline and excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco in the euro area2. Point forecasts are also solicited for labour cost, Brent crude oil price, USD/EUR exchange rate and the ECB’s interest rate for its main refinancing operations. The Bank of England has been conducting the quarterly Survey of External Forecasters since 1996, covering participants from city firms, academic institutions and private consultancies, predominantly based in London. The survey collects point forecasts of inflation, GDP growth, unemployment rate, Bank Rate, etc., for the next three years. The results of the survey are regularly published in the Bank’s Inflation Report. The Central Bank of Brazil conducts the ‘Focus Survey’ for monitoring the market expectations on inflation, output growth and other fiscal and external indicators on a daily basis3. The survey is canvassed among 140 banks, asset managers and other institutions including real sector companies, brokers, consultancies, etc. The quarterly Survey of Expectations conducted by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand collects point forecasts of inflation, real output growth, unemployment rate, besides a few financial market variables with a focus on inflation indicators. Inflation forecasts are collected for the short-term and longterm4, while real GDP growth forecasts are collected for the next two-years. The survey covers both business managers and professionals. The review suggests that central banks in many countries widely use the survey of professional forecasters to assess their expectations on important macroeconomic indicators. Such surveys also enable to assess the uncertainty prevailing in the economy. Their views provide valuable insights in setting the near to medium-term economic outlook. III. Revisions in SPF Median Forecasts of Select Macroeconomic Indicators During March 2018 to March 2019, seven SPF rounds were conducted (51st round to 57th round) by the Reserve Bank. The annual forecasts for national accounts aggregates for 2018-19 were collected till the March 2019 round5. III.1. Annual Forecasts for 2018-19 Forecasts of real GDP growth for 2018-19 remained unchanged at 7.4 per cent during the survey rounds conducted during May 2018 to November 2018. These were subsequently revised down by 20 basis points (bps) each over the subsequent two rounds to 7.0 per cent by March 2019 (Table 1). Concomitantly, the forecast path of growth in real gross value added (GVA) was also revised down. The downward revisions in the GDP growth forecasts since the November 2018 round of the survey coincided with the downward revision in the real GDP growth published by the National Statistical Office (NSO)6. The initial median SPF forecast of GDP growth in 2018-19 was about 50 bps higher when compared to the official estimate of 6.8 per cent (provisional) released subsequently. The lowering of growth forecasts by the professional forecasters was concomitant with the downward revision in the real gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) growth rate by the NSO7 and decline in certain high frequency indicators such as domestic production of capital goods8 and consumption of finished steel. Incidentally, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) also revised down the world GDP growth forecast for 2019 from 3.7 per cent projected in October 2018 to 3.5 per cent in January 2019, which is an indication of global demand conditions turning adverse for India’s outlook for GDP growth and exports. The median forecast of average headline CPI inflation for 2018-19 remained in the range of 4.5- 4.7 per cent during the survey rounds conducted during March-September 2018, which was revised down to 3.4 per cent in the March 2019 round of the survey. While March 2019 forecasts matched the realised inflation rate, initial forecasts overestimated it by about 110 to 130 bps. Forecast of inflation in ‘CPI excluding food and beverages, fuel and light, pan, tobacco and intoxicants’ (hereinafter called ‘exclusion based CPI’) was revised up from 5.1 per cent in the March 2018 round to 5.8 per cent in the March 2019 round, which matched the actual print. The consistent downward revision in forecasts of headline inflation, combined with the stability in forecasts of exclusion based CPI inflation since the September 2018 round, suggest consistent moderation in inflation assessment for food and fuel during the course of the year9. The subdued realised food inflation, and the deflation over five consecutive months starting with October 2018, contributed to the downward revisions in the headline inflation projection path. | Table 1: Annual Median Forecasts of Important Economic Variables for the Year 2018-19 | | Survey Period | Mar-18 | May-18 | Jul-18 | Sep-18 | Nov-18 | Jan-19 | Mar-19 | | Survey Round | 51st Round | 52nd Round | 53rd Round | 54th Round | 55th Round | 56th Round | 57th Round | | GDP growth at market prices at constant prices | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.0 | | GVA growth at basic prices at constant prices | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 6.8 | | CPI headline inflation | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | | CPI excluding food & beverages, fuel & light and pan, tobacco & intoxicants inflation | 5.1 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.8 | | WPI headline inflation | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.3 | | WPI non-food manufactured products inflation | 3.3 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.2 | | Current account balance (as per cent of GDP) | -2.1 | -2.4 | -2.5 | -2.7 | -2.7 | -2.5 | -2.4 | | Centre’s fiscal deficit (as per cent of GDP) | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 | | Combined fiscal deficit (as per cent of GDP) | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.4 | The current account deficit (CAD) for 2018-19 was pegged at 2.1 per cent (as per cent of GDP at current market value) in the March 2018 round of the survey, which was gradually revised up to 2.7 per cent in the November 2018 round, in tandem with the rise in crude oil prices and the depreciation of the Indian Rupee during this period. The Indian crude oil basket prices increased by about 25.0 per cent from US$ 63.9 per barrel in March 2018 to around US$ 80.0 per barrel in October 2018. During the same period, the Indian Rupee also depreciated by around 12.0 per cent against the US Dollar. With the subsequent drop in the Indian crude oil basket prices and appreciation of the Rupee, forecast of CAD was revised down to 2.4 per cent in the March 2019 round of the survey. The actual CAD for the year turned out to be 2.1 per cent of GDP, which is what the professional forecasters had projected at the beginning of the year. Forecasts of centre’s fiscal deficit (as per cent of GDP at current market prices) remained unchanged at 3.3 per cent till the November 2018 round of the survey and subsequently revised up to 3.4 per cent in the March 2019 round, which was same as the actual outcome. Forecasts of combined fiscal deficit of central and state governments remained in the range of 6.1- 6.4 per cent all through the year, which was in line with the actual print of 6.2 per cent. III.2. Annual Forecast for 2019-20 The median GDP growth forecast for 2019-20 was placed at around 7.5 per cent in the initial four rounds of the survey conducted during May 2018 to November 2018 (Table 2), which was revised down by 20 bps to 7.3 per cent in the January 2019 round and further by 30 bps to 6.9 per cent in the July 2019 round. After the release of the GDP growth numbers for the first quarter of 2019-20 (5.0 per cent) by the NSO, in the September 2019 round, median forecast of GDP growth for 2019-20 was further revised down to 6.2 per cent, about 130 bps lower than initial forecasts reported during May 2018 to November 2018 round. The downward revision in GDP growth forecast reflected both subdued domestic demand conditions and weak consumer sentiments. Forecast of real private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) growth was revised down by 250 bps from 8.0 per cent in the May 2019 round to 5.5 per cent in the September 2019 round, reflecting lower households demand as indicated by moderation in the production of consumer durables10. Forecast of real GFCF growth rate was revised down cumulatively by 340 bps during March 2019 to September 2019. | Table 2: Annual Median Forecasts of Important Economic Variables for the Year 2019-20 | | Survey Period | May-18 | Jul-18 | Sep-18 | Nov-18 | Jan-19 | Mar-19 | May-19 | Jul-19 | Sep-19 | | Survey Round | 52nd Round | 53rd Round | 54th Round | 55th Round | 56th Round | 57th Round | 58th Round | 59th Round | 60th Round | | GDP growth at market prices at constant prices | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.2 | | PFCE growth at constant prices | - | - | - | - | - | 8.1 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 5.5 | | GFCF growth at constant prices | - | - | - | - | - | 9.4 | 9.2 | 7.6 | 6.0 | | GVA growth at basic prices at constant prices | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 6.0 | | CPI headline inflation | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.5 | | CPI excluding food & beverages, fuel & light and pan, tobacco & intoxicants inflation | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 4.2 | | WPI headline inflation | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1.8 | | WPI non-food manufactured products inflation | 3.1 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.5 | | Current account balance (as per cent of GDP) | -2.4 | -2.5 | -2.5 | -2.6 | -2.3 | -2.3 | -2.2 | -2.0 | -1.9 | | Centre’s fiscal deficit (as per cent of GDP) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | | Combined fiscal deficit (as per cent of GDP) | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 6.1 | The median forecasts of inflation for 2019-20 were also revised down significantly since the November 2018 round of the survey. During the September 2018 round and November 2018 round, the average inflation for 2019-20 was pegged at 4.8 per cent by the professional forecasters, which was revised down gradually over the next five rounds by 130 bps to 3.5 per cent in the September 2019 round. The forecast of exclusion based CPI inflation was revised down successively from 5.2 per cent in the January 2019 round to 4.1 per cent in the July 2019 before revising up marginally to 4.2 per cent in the September 2019 round, in synchrony with the successive downward revision in GDP growth during the period. Headline CPI inflation forecast remained reasonably stable during last four rounds of the survey even as exclusion based CPI inflation forecasts were revised down, implicitly suggesting higher food inflation expectation during this period. The downward revision in the exclusion based CPI inflation forecasts were attendant to the widening of negative output gap, softening of crude oil prices and an appreciation of the Indian Rupee against the US Dollar during the period. Inflation forecasts for WPI headline and WPI non-food manufactured products for 2019-20 were also revised down over this period and stood at 1.8 per cent and 0.5 per cent, respectively, in the September 2019 round. The median forecast of CAD to GDP ratio for 2019-20 was revised up from 2.4 per cent in the May 2018 round to 2.6 per cent in the November 2018 round. The forecast was subsequently revised down to 1.9 per cent in the September 2019 round, on account of softening of crude oil prices, appreciation of the domestic currency as well as lower domestic demand. III.3. Revisions in Quarterly Growth Path Quarterly output growth forecast path for the first three quarters of 2018-19 broadly remained unchanged, with forecast for Q3:2018-19 remaining within the range of 6.9-7.2 per cent in the survey rounds conducted during March 2018 to January 2019 (Table 3). For Q4:2018-19, growth forecast was successively revised down from 7.3 per cent in the May 2018 round to 6.5 per cent in the March 2019 round, while the actual print was lower at 5.8 per cent. For the year 2019-20, the output growth forecast path was revised down significantly since the January 2019 round of the survey. For Q1:2019-20, growth forecast was revised down from 7.2 per cent in the November 2018 round to 6.1 per cent in the July 2019 round. The extent of downward revision in the last three rounds of the survey was more prominent for the near term11, while the downward revision for three and four quarter horizons has been relatively less. The continued slowdown in the domestic private consumption demand and investment growth, coupled with likely lower global output growth, led to downward revision in the GDP growth forecast path. | Table 3: Quarterly Median Forecasts of GDP Growth | | Survey period | Mar-18 | May-18 | Jul-18 | Sep-18 | Nov-18 | Jan-19 | Mar-19 | May-19 | Jul-19 | Sep-19 | | Survey Round | 51st Round | 52nd Round | 53rd Round | 54th Round | 55th Round | 56th Round | 57th Round | 58th Round | 59th Round | 60th Round | | GDP growth rate | | Q1: 2018-19 | 7.3 | 7.3 | | | | | | | | | | Q2: 2018-19 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.4 | | | | | | | | Q3: 2018-19 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.9 | | | | | | Q4: 2018-19 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.5 | | | | | Q1: 2019-20 | | | 7.5 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.1 | | | Q2: 2019-20 | | | | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.7 | 5.8 | | Q3: 2019-20 | | | | | | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 6.4 | | Q4: 2019-20 | | | | | | | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.2 | | Q1: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.2 | III.4. Revisions in Quarterly Inflation Path Taking into account the evolving macroeconomic conditions and incoming economic data, the professional forecasters revised their forecasts of quarterly inflation path for 2019-20 and for Q1:2020-21 in different rounds of the survey (Table 4). Median forecasts for quarterly CPI headline inflation path were generally revised down in every successive round for all the quarters of 2019-20 as also for Q1:2020-21. | Table 4: Quarterly Median Forecasts of Inflation | | Survey Period | Mar-18 | May-18 | Jul-18 | Sep-18 | Nov-18 | Jan-19 | Mar-19 | May-19 | Jul-19 | Sep-19 | | Survey Round | 51st Round | 52nd Round | 53rd Round | 54th Round | 55th Round | 56th Round | 57th Round | 58th Round | 59th Round | 60th Round | | CPI Headline Inflation | | Q1: 2018-19 | 5.1 | 5.0 | | | | | | | | | | Q2: 2018-19 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.1 | | | | | | | | Q3: 2018-19 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.1 | | | | | | | Q4: 2018-19 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 2.4 | | | | | Q1: 2019-20 | | | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | | | | Q2: 2019-20 | | | | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | | Q3: 2019-20 | | | | | | 4.4 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.7 | | Q4: 2019-20 | | | | | | | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.9 | | Q1: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.9 | | Q2: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | | | 4.0 | | CPI ex Food, Fuel, Pan, Tobacco and Toxicants Inflation | | Q1: 2018-19 | 5.5 | 6.1 | | | | | | | | | | Q2: 2018-19 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.0 | | | | | | | | Q3: 2018-19 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 6.0 | | | | | | | Q4: 2018-19 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.3 | | | | | Q1: 2019-20 | | | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.5 | | | | Q2: 2019-20 | | | | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 4.2 | | Q3: 2019-20 | | | | | | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 3.9 | | Q4: 2019-20 | | | | | | | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 4.2 | | Q1: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | 5.0 | 4.4 | 4.4 | | Q2: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | | | 4.3 | | WPI Headline Inflation | | Q1: 2018-19 | 3.8 | 4.1 | | | | | | | | | | Q2: 2018-19 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 4.8 | | | | | | | | Q3: 2018-19 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 5.0 | | | | | | | Q4: 2018-19 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.9 | | | | | Q1: 2019-20 | | | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.0 | | | | Q2: 2019-20 | | | | 3.6 | 4.4 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 1.1 | | Q3: 2019-20 | | | | | | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.0 | | Q4: 2019-20 | | | | | | | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 2.2 | | Q1: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | 3.9 | 2.8 | 2.2 | | Q2: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | | | 2.8 | | WPI Non-food Manufactured Products Inflation | | Q1: 2018-19 | 3.6 | 3.8 | | | | | | | | | | Q2: 2018-19 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | | | | | | | | Q3: 2018-19 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.8 | | | | | | | Q4: 2018-19 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | | | | | Q1: 2019-20 | | | 2.6 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 2.0 | | | | Q2: 2019-20 | | | | 3.3 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | | Q3: 2019-20 | | | | | | 4.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.5 | -0.2 | | Q4: 2019-20 | | | | | | | 3.0 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.6 | | Q1: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | | Q2: 2020-21 | | | | | | | | | | 2.0 | CPI headline inflation forecast for Q1:2019-20 was revised down from 5.1 per cent in the July 2018 round to 3.1 per cent in the May 2019 round12, with substantial downward revision made during the November 2018 to the March 2019 rounds. The decline in headline inflation forecasts may be attributed to low food inflation as well as softening in energy prices. Forecasts of exclusion based CPI inflation for Q1:2019-20 were also sequentially revised down from the November 2018 round to the May 2019 round. Headline inflation forecast for Q2:2019-20 was revised down successively from 5.1 per cent in the September 2018 round to 3.3 per cent in the September 2019 round, while forecast of exclusion based CPI inflation was revised down from 5.4 per cent in the November 2018 round to 4.2 per cent in the September 2019 round. The initial uncertainty surrounding the progress of South-west monsoon for 2019 led to some firming up of food inflation expectations, which led to upward revision in the headline inflation forecast during the May 2019 round for the near term forecast horizon. On the other hand, forecast for exclusion based CPI inflation continued to be revised down, despite an increase in the crude oil prices during January 2019 to May 2019, reflecting lower than expected growth in domestic demand. The quarterly forecast paths for WPI headline inflation and WPI non-food manufactured products inflation were revised up during March 2018 to November 2018, for all the quarters till Q2:2019-20 and revised down thereafter. The actual prints of WPI headline inflation and WPI non-food manufactured products inflation turned out to be higher than the forecasts for Q1 and Q2 of 2018-19, but matched the final estimates of 2.9 per cent and 2.7 per cent, respectively, for Q4:2018-19. The quarterly forecast paths for 2019-20 have largely been revised down since the November 2018 round. IV. Empirical Assessment of Forecasts IV.1. Accuracy of the Quarterly Forecasts The accuracy of the median SPF forecasts during Q1:2014-15 to Q2:2019-20 has been empirically tested for three important quarterly indicators, viz., (i) output growth measured using real GVA, (ii) headline CPI inflation, and (iii) exclusion based CPI inflation. Forecast errors have been analysed in terms of three alternative criteria, viz., (a) the mean error (ME), (b) the mean absolute error (MAE) and (c) the root mean squared error (RMSE) as described below: MAE and RMSE are more popular measures since they do not allow for cancelling out of errors in opposite directions. Even though these two measures assess the absolute size of errors quite well, they do not measure the important aspect of average bias in forecasts, which is estimated by the mean error (ME). Recently, these measures have been used to compare the inflation forecast performance of India with some other countries (Raj, et. al., 2019). The comparison of forecast accuracy for GVA13 growth, CPI inflation and exclusion based CPI inflation are presented in Table 5. All measures indicate that forecast performance improves with reduction in forecast horizon, indicating forecasters’ tendency to update their forecast with incoming new information and provide more accurate updated estimates as they approach closer to the final official data release of the underlying indicator. During the reference period, the SPF panellists over-predicted headline CPI inflation, as reflected in negative mean errors, where the average upward bias was (-)100 bps (Table 5, panel a). In contrast, the forecasts of exclusion based CPI inflation had no systematic bias during the reference period. GVA growth forecasts had marginal upward bias, with average mean error of (-)10 bps. | Table 5: Forecast Errors | | (Percentage points) | | Item | GVA | Headline CPI inflation | Exclusion based CPI inflation | | a. Mean Error | | | | | 1-quarter ahead error | 0.1 | -0.5 | -0.3 | | 2-quarter ahead error | 0.0 | -0.9 | -0.1 | | 3-quarter ahead error | -0.1 | -1.3 | 0.1 | | 4-quarter ahead error | -0.2 | -1.4 | 0.2 | | Average | -0.1 | -1.0 | 0.0 | | b. Mean Absolute Error | | | | | 1-quarter ahead error | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | | 2-quarter ahead error | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | | 3-quarter ahead error | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | | 4-quarter ahead error | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.1 | | Average | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | | c. Root Mean Squared Error | | | | | 1-quarter ahead error | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | | 2-quarter ahead error | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | | 3-quarter ahead error | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.6 | | 4-quarter ahead error | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | | Average | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.3 | Mean absolute error as well as RMSE were generally lower for GVA growth as compared to CPI inflation for all forecast horizons. The mean absolute error (averaged across all the four forecast horizons) was 90 bps for GVA growth as compared to 110 bps and 80 bps, for headline CPI inflation and exclusion based CPI inflation, respectively (Table 5, panel b). The RMSE for GVA growth was 100 bps whereas for CPI inflation and exclusion based CPI inflation, it averaged 150 bps and 130 bps, respectively (Table 5, panel c). The statistical significance of the errors has been addressed in the next section, with the caveat of relatively small sample period. IV.2. Testing for Efficiency of the Forecasts An efficient forecast makes use of all the available information at the time of making the forecast and its error should ideally not be systematically correlated with the information which is available at the time of generating forecasts. Accordingly, the realised inflation / growth should not be related to the forecast error (Raj, op. cit. (2019)). Consider,  For an efficient forecast, the coefficient βq should be statistically insignificant. In view of the relatively limited sample size, we restrict the analysis only to one- and two- quarters ahead forecasts. The forecasts are found to be efficient for headline CPI inflation and exclusion based CPI inflation for both the forecast horizons. On the other hand, GVA growth forecasts are found to be efficient for two-quarters ahead horizon but, for one-quarter ahead horizon, the test rejects the null hypothesis that forecasts are efficient. (Table 6). In this context, it is important to note that unlike CPI data, which are not revised after one and half month from the reference period, GVA estimates undergo revisions more than once. | Table 6: Efficiency Test | | | One quarter ahead | Two quarter ahead | | | Estimate | s.e. | p-value | Estimate | s.e. | p-value | | GVA | αq | -2.84 | 1.42 | 0.07 | -2.36 | 1.79 | 0.21 | | | βq | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.19 | | Headline CPI Inflation | αq | 0.17 | 0.55 | 0.76 | -1.27 | 0.78 | 0.12 | | | βq | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.44 | | Exclusion based CPI Inflation | αq | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.21 | -0.53 | 1.09 | 0.64 | | | βq | -0.19 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.77 | V. Disagreement and Uncertainty in Forecasts Risk and uncertainty are integral part of any forecasting exercise and macroeconomic predictions are no exceptions. Uncertainty in forecasting arises from inherent randomness of the economic process and inter-linkages. Understanding the process of expectation formation and measurement of forecast uncertainty are crucial inputs for effective policy-making. Nevertheless, in practice, measuring uncertainty is challenging due to the twin problem of measuring individual forecaster’s subjective assessment as well as unavailability of data on economic uncertainty. Although most of the forecast surveys provide a direct measure of expectation, the scope for measuring uncertainty is limited since only a handful of surveys collect information on both point forecasts as well as density forecasts, the latter providing the information for measuring uncertainty. Surveys that collect both point and density forecasts can be used to construct measures of uncertainty and their relationship with forecast disagreement and predictive accuracy. As the SPF collects point and density forecasts of key economic variables, viz., output growth and inflation rate, uncertainty and disagreement measures are compiled based on those respondents who provided both information. Drawing upon the work of Zarnowitz and Lambros (1987), forecast uncertainty is measured under the assumption of a uniform probability distribution within each interval of the density forecast. The measure of disagreement is based on the variability in the point forecasts of the individual forecasters for growth and inflation in the qth round of the SPF at the time point t. The disagreement measures for GVA growth have remained mostly below its medium term average for all the forecast horizons in recent period (Chart 1). In the case of CPI headline inflation, for one-quarter ahead forecast horizon, disagreement has declined in the recent period and remained below its average level of 0.4 (Chart 2). For the remaining forecast horizons, disagreement measures remained largely below the respective average values in the last few quarters.

In case of exclusion based CPI inflation, the disagreement in one-quarter ahead forecasts remained mostly below the average level, except for few quarters in the recent period, where sudden spikes were observed (Chart 3). Inflation uncertainty measures for the quarterly forecasts declined for the first two quarters of 2019-20 since the November 2018 round (55th round) (Chart 4, left panel). In case of real GDP growth for 2019-20, uncertainty remained almost stable since the May 2019 round (58th round), while for 2020-21, uncertainty witnessed an uptick in the last round of the survey. VI. Conclusion Professional forecasters regularly monitor evolving macro-economic conditions and their expectations provide valuable input in forming the near-term and medium-term economic outlook. In the Reserve Bank’s regular survey, forecasters revised down their growth and inflation projections in successive survey rounds in the recent period. Forecasts of both output growth and inflation for 2018-19 and 2019-20 have been revised down. For the exclusion based CPI inflation, the forecast path was gradually revised up for 2018-19 but was lowered for 2019-20. Though the forecasters have revised both headline CPI inflation and exclusion based CPI inflation, the magnitude of forecast errors were of lower order in case of latter, reflecting relatively stable nature of exclusion based CPI inflation. The downward revisions in exclusion based CPI inflation forecaster for 2019-20 were in consonance with the downward revisions in growth forecasts. For 2018-19, the forecasts for CPI headline inflation and GDP growth had positive bias. Also, the disagreement on inflation forecasts has reduced in the recent period, coinciding with the moderation in the inflation volatility, particularly after 2017. Empirical analysis shows that the forecasts were generally efficient in terms of incorporating available information and there has been more agreement on growth and headline inflation outlook among the forecasters in the recent period. Further, the accuracy of forecasts improved as the forecast horizon narrowed. References Abel Joshua, Rich Robert, Song Joseph and Tracy Joseph (2016), ‘The Measurement and Behavior of Uncertainty: Evidence from the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters’, Journal of Applied Econometrics 31: 533–550. Croushore Dean (1993), ‘Introducing: The Survey of Professional Forecasters’, Business Review, Issue November, 3-15. Raj Janak, Kapur Muneesh, Das Praggya, George Asish Thomas, Wahi Garima and Kumar Pawan (2019), ‘Inflation Forecasts: Recent Experience in India and a Cross-country Assessment’, Reserve Bank of India Mint Street Memo, 05/2019. RBI Data Release of Survey of Professional Forecasters (various issues). (https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BimonthlyPublications.aspx?head=Survey%20of%20 Professional%20Forecasters%20-%20Bi-monthly) Zarnowitz Victor and Lambros Louis A (1987), ‘Consensus and uncertainty in economic prediction’, Journal of Political Economy 95: 591–621.

|