During 2017-18, the banking sector continued to grapple with the problems of deteriorating asset quality and declining profitability. In order to align the resolution process with the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016, the framework for resolution of stressed assets was revised and the previous schemes were withdrawn. Customer rights were strengthened by limiting liability of customers in unauthorised electronic banking transactions. Further, given the increasing popularity of digital payments medium, data protection and cyber security norms were strengthened. For effective and timely redressal of grievances of customers of Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs), an Ombudsman Scheme for deposit taking NBFCs was initiated. Regulatory policies for cooperative banks were further harmonised with those of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs). In order to bring about ownership-neutral regulations, government-owned NBFCs will be required to adhere to the Bank’s prudential regulations in a phased manner. VI.1 The Indian banking sector continued to experience deterioration in asset quality, which had a significant impact on their profitability and their capacity to support credit growth. In response to mounting delinquent loans of banks, and in order to align the resolution process with the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016, the framework for resolution of stressed assets was revised, and the previous schemes were withdrawn. Further, the various processes and input constraints that were embedded in earlier regulatory schemes for restructuring were removed. In order to keep a close watch on financial stability risks, network analysis for the financial conglomerates in various market segments is proposed to be carried out to assess the systemic risks posed by these institutions. Given the increasing popularity of digital payments, data protection and cyber security norms were strengthened. Know Your Customer (KYC) norms were modulated further to make them more effective. VI.2 Furthermore, for effective and timely redressal of grievances of customers of NBFCs, an Ombudsman Scheme for deposit taking NBFCs was initiated. Though implementation of Indian Accounting Standards (Ind AS) in case of SCBs has been postponed for one year due to lack of necessary legislative amendments, NBFCs with net worth of ₹5 billion and above are required to implement Ind AS from April 1, 2018. In order to bring about ownership-neutral regulations, government-owned NBFCs will now be required to adhere to the Bank’s prudential regulations in a phased manner. In order to further harmonise regulatory policies for cooperative banks, the regulatory process for opening current account with the Reserve Bank was simplified for these banks. Fine-tuning of the regulatory and supervisory policies is expected to further strengthen the resilience and robustness of the banking system. FINANCIAL STABILITY UNIT (FSU) VI.3 The mandate of FSU is to monitor stability related matters with the objective of strengthening the financial system. FSU implements this mandate by examining the risks to financial stability, undertaking macro-prudential surveillance through systemic stress tests and other tools as well as disseminating information on status of and challenges to financial stability through the Financial Stability Report (FSR). It also functions as a secretariat to the Sub-Committee of the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC), a co-ordination council of regulators for maintaining financial stability and monitoring macro-prudential regulation in the country. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status VI.4 As planned, FSR was published in June 2017 and December 2017. With a view to strengthening the stress testing framework, the methodology for estimating sectoral probability of defaults was reinforced further while the methodology for projecting capital to risk-weighted asset ratio (CRAR) was revised by estimating risk weighted assets dynamically using the internal ratings based formula. The results based on these methodologies were published in FSR. Further, contagion (network) analysis was expanded to urban cooperative banks as well. VI.5 The FSDC Sub-Committee held two meetings in 2017-18 and reviewed various issues including the establishment of National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE), operationalisation of information utilities registered by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI), sharing of data among regulators, implementation status of Legal Entity Identifier (LEI), framework for systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs), implementation of common stewardship code for the Indian financial sector, single entity undertaking multiple activities and review of Central KYC Registry (CKYCR). The Sub- Committee also reviewed the status of corporate insolvency resolution process, activities of its various technical groups and the functioning of State Level Coordination Committees (SLCCs) in various states/UTs. The recommendations of the Working Group on FinTech and Digital Banking, Shadow Banking Implementation Group, credit cycles and financial stability, Investor Education and Protection Fund (IEPF), action taken on shell companies, legal framework for cross-border insolvency and issues regarding acceptance of deposits under the Companies Act were the other issues discussed. VI.6 Inter-Regulatory Technical Group (IRTG), which is a sub-group of the FSDC Sub-Committee, held two meetings during the year and discussed issues relating to the KYC process due to amendments in the Prevention of Money Laundering (PML) rules, implementation of the risk based supervision in the National Pension Scheme (NPS) Architecture, implementation status of LEI, data sharing among regulators and technical specifications for account aggregators. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.7 In the year ahead, FSU will continue to conduct macro-prudential surveillance, publish the FSR and conduct meetings of the FSDC Sub- Committee and IRTG. In addition, the current stress testing framework / methodology will be strengthened so as to eventually migrate to the stressed scenario-based supervisory capital requirement for banks. In addition, the contagion analysis will be extended to NBFCs. REGULATION OF FINANCIAL INTERMEDIARIES Commercial Banks: Department of Banking Regulation (DBR) VI.8 DBR is the nodal department for regulation of SCBs. Apart from financial stability, it focuses on developing an inclusive and competitive banking structure through appropriate regulatory measures. The regulatory framework is fine-tuned as per the requirements of the Indian economy while suitably adapting to the international best practices. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status Introduction of Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) for Large Corporate Borrowers VI.9 Banks were directed to advise their existing large corporate borrowers (i.e., those having total exposure of ₹500 million and above) to obtain LEI during March 31, 2018 to December 31, 2019. Borrowers in this category, who do not obtain LEI are not to be granted renewal / enhancement of credit facilities. Banks should encourage large borrowers to obtain LEI for their parent as well as all subsidiaries and associates. Withdrawal of Previous Schemes for Resolution of Stressed Assets VI.10 The Reserve Bank had to introduce various schemes such as the Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR) scheme, Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A), Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) scheme and Joint Lenders’ Forum (JLF) that aimed at structured resolution of stressed assets as there was no comprehensive insolvency and bankruptcy law in the country then. The schemes were designed to emulate the desirable attributes of a bankruptcy law, as identified in the related literature, with built-in incentives for the lenders to encourage adoption and consequent resolution. In view of the enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016, the need for such specific schemes/guidelines was obviated and consequently, the previous schemes/ guidelines such as SDR, S4A, CDR and JLF stood withdrawn from February 12, 2018. These have now been substituted with a harmonized and simplified framework for resolution of stressed assets (Box VI.1). Box VI.1

Resolution of Stressed Assets – Revised Framework Studies have shown that reducing the levels of non-performing loans has a positive medium term impact on an economy. On the other hand, when the problem is ignored, economic performance would suffer; specifically, it has been estimated that the growth foregone due to an overhang of non-performing loans can be in excess of two percentage points annually till the problem is resolved (Balova et al., 2016). The experience of Japan in the early 1990s shows that economic stagnation can cause new non-performing loans to emerge rapidly, and deplete bank capital. On the contrary, a quick and efficient resolution of banking crises prevents the possibility of strong negative economic effects, and the related structural policy reforms might even result in favourable economic effects, as was demonstrated in the Nordic experience (Steigum 2010). While there are many strategies for resolution of bad loans, a hybrid approach involving out of court restructuring and a formal insolvency process in the judicial system is a recommended tool for resolution (BIS 2017). For a long time, India did not have a bankruptcy law in place, and hence the Reserve Bank had to introduce various restructuring frameworks which were designed to emulate the desirable attributes of a bankruptcy law. These were interspersed with incentives for the lenders to adopt the schemes and effect an early resolution. However, these schemes were generally applied by banks to avail of asset classification benefits, with very little efforts towards resolution of the underlying stress. It has been argued in the context of the experience of Japan in the 1990s and the OECD countries (McGowan et al., 2017) in the 2000s that forbearance in lending props up inefficient firms and encourages them not to undertake corrective efforts, thus leading to sustenance of zombie firms in an economy. The latter study has also documented the adverse effects that prevalence of zombie companies can have on the growth in investment and employment, and ease of entry to young firms and their ability to upscale. Acharya et al. (2016) has documented the effects of zombie congestion emanating from the credit misallocation due to windfall gains enjoyed by weakly capitalized banks from the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme of the European Central Bank, on the investment and employment growth of non-zombie firms in the European context. Breaking the vicious circle of forbearance in lending and perverse adoption of resolution schemes, which feed on each other, requires a strong presence of bankruptcy laws in a country. The enactment of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) and the amendment to the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 empowering the Reserve Bank to leverage the IBC mechanism for resolving specific stressed accounts, have provided a real opportunity to address the above challenges. The Reserve Bank has taken certain steps over the last few months in this direction with a focus on certain large value stressed accounts. The ‘revised framework for resolution of stressed assets’, issued by the Reserve Bank on February 12, 2018 must be seen as a step towards laying down a steady-state approach for ensuring early resolution of stressed assets in a transparent and time-bound manner so that the maximum value could be realized by the lenders. The revised framework, while leaving the definition of a non-performing asset unchanged, lays down broad principles that should be followed while undertaking the resolution of stressed assets, with bright line tests for ensuring credible outcomes. The underlying theme of the revised framework is to provide as much flexibility as possible to the lenders and the stressed borrowers but, at the same time ensure that the resolution plan is implemented within a timeframe and that the resolution plan is credible. If lenders and the large stressed borrowers are unable to put in place a credible resolution plan within the timelines, they would be required to go through the structured insolvency resolution process under the IBC. The revised framework also attempts to instil the requisite discipline mechanism for a one-day default in the context of bank loans, akin to the market discipline to which the borrowers raising money through debt markets are subject. With defaults being reported to a central database, which is accessible to all banks, the credit discipline is expected to improve significantly. Nevertheless, default in payment is a lagging indicator of financial stress of a borrower and therefore, lenders need to be proactive in credit monitoring to identify financial stress at an early stage rather than wait for a borrower to default. Early identification of stress would provide sufficient time for lenders to put in place the required resolution plan. Another major change that has been introduced is that resolution plans can now be implemented individually or jointly by lenders. Complete discretion and flexibility has been given to the banks to formulate their own ground rules in dealing with the borrowers who have exposures with multiple banks. Under the revised framework, the lenders can implement differential resolution plans that are tailored to their internal policies and risk appetite. To ensure that only credible resolution plans are implemented, a framework of independent affirmation has been introduced through the requirement of independent credit opinions on the proposed plan by empaneled credit rating agencies. Taken as a whole, the revised framework attempts to improve the credit culture in the country and the trust between counterparties in a transaction. This will be critical in ensuring sufficient incentives for the banks to effectively carry out their role as delegated monitors of loans. References: 1. Acharya, V.V., T. Eisert, C. Eufinger, and C.W. Hirsch (2016), ‘Whatever it takes: The real effects of unconventional monetary policy’, Working Paper, New York University Stern School of Business. 2. Balova, M., Nies, M., and Plekhanov, A (2016), “The Economic Impact of reducing non- performing loans”, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Working Paper No. 193. 3. BIS (2017), “Resolution of non-performing loans – policy options”, FSI Insights on policy implements No. 3. 4. McGowan, M. A., Andrews, D., Millot, V. (2017), The Walking Dead? Zombie Firms and Productivity Performance in OECD Countries, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1372. 5. Steigum, E. (2010), “The Norwegian Banking Crisis in the 1990s: Effects and Lessons”, Norwegian School of Management, Norway. | Mechanism to Extend Banking Facility for Senior Citizens and Differently Abled Persons VI.11 Banks were advised in November 2017 to put in place appropriate mechanisms to extend banking facilities to senior citizens and differently abled persons. Limiting Liability of Customers in Unauthorised Electronic Banking Transactions VI.12 The Annual Conference of Banking Ombudsmen, 2014 had suggested that banks and Indian Bankers’ Association (IBA) should formulate a policy on zero liability of customers in electronic banking transactions, in cases where the bank was unable to establish customer level negligence. The final circular providing the framework for limiting the customer’s liability in unauthorised/fraudulent electronic transactions was issued on July 6, 2017 after taking into consideration the comments received from banks and the public (Box VI.2). Basel III Framework on Liquidity Standards VI.13 Following an amendment to the guidelines on Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), banks incorporated in India are now permitted to recognise cash reserves held with foreign central banks in excess of the reserve requirements as Level 1 High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA), in cases where a foreign sovereign has been assigned a zero per cent risk weight by an international rating agency. In cases where a foreign sovereign has been assigned a non-zero per cent risk weight by an international rating agency, but a zero per cent risk weight has been assigned at national discretion under Basel II framework, reserves held with such foreign central banks in excess of the reserve requirement would be allowed to be treated as Level 1 HQLA, to the extent that these balances cover the bank’s stressed net cash outflows in that specific currency. As per the existing roadmap, SCBs have to reach the minimum LCR of 100 per cent by January 1, 2019. The assets allowed as Level 1 HQLA for the purpose of computing LCR of banks include, inter alia, government securities in excess of the minimum SLR requirement and, within the mandatory SLR requirement, government securities to the extent allowed by the Reserve Bank under the Marginal Standing Facility (MSF) [presently 2 per cent of the bank’s net demand and time liabilities (NDTL)] and under the Facility to Avail Liquidity for Liquidity Coverage Ratio (FALLCR) (this has been increased from 9 per cent to 11 per cent of the bank’s NDTL). Hence, the total carve-out from SLR available to banks is 13 per cent of their NDTL. The other prescriptions in respect of LCR remain unchanged. Box VI.2

The Framework on Limiting Liability of Customers in Unauthorised Electronic Banking Transactions The salient features of the framework on limiting liability of customers in unauthorised electronic banking transactions are as follows: Zero Liability: A customer need not bear any loss if the deficiency is on the part of the bank and in cases where the fault lies neither with the bank nor with the customer but lies elsewhere in the system and the customer notifies the bank within three working days of receiving the communication from the bank about the unauthorised transaction. Limited Liability: Where the loss is due to customer’s negligence, the customer has to bear the entire loss until the unauthorised transaction is reported to the bank. In cases where the fault lies neither with the customer nor with the bank but lies elsewhere in the system and the customer reports the unauthorised transaction with a delay of four to seven working days after receiving the communication about the transaction, the maximum liability of the customer ranges from ₹5,000 to ₹25,000, depending on the type of account/instrument. Liability as per Board approved policy: If the unauthorised transaction is reported beyond seven working days, the customer liability shall be determined as per the bank’s Board approved policy. The bank is required to credit (shadow reversal) the amount involved in the unauthorised electronic transaction to the customer’s account within 10 working days from the date of notification by the customer. The bank has to resolve the complaint and establish the liability of the customer, if any, within 90 days of the receipt of the complaint. Further, banks have been mandated to require the customers to register their mobile numbers for SMS alerts and for electronic transactions. | VI.14 Final guidelines on Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) were issued in May 2018. Encouraging Formalisation of MSME Sector VI.15 In February 2018, exposure of banks and NBFCs to the GST-registered Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) was permitted to be classified as a standard asset, as per a 180-day past due criterion, subject to certain conditions, including a cap of ₹250 million on the aggregate exposure. On a review, the benefits have now been extended to all MSMEs with aggregate credit facilities up to the above limit, including those which are yet to register under the GST (i.e., goods and services tax). Accordingly, such MSME accounts shall continue to be classified as standard by banks and NBFCs if the amounts overdue as on September 1, 2017 and payments due between September 1, 2017 and December 31, 2018 were/are paid no later than 180 days from the original due date. In view of the benefits from increasing formalisation of the economy for financial stability, the dues payable from January 1, 2019 onwards shall be aligned to the extant 90 days NPA norm in a phased manner in case of the GST-registered MSMEs. The MSMEs that are not GST-registered as on December 31, 2018 shall revert to 90 day NPA norm immediately from January 1, 2019. Credit Information Companies to Furnish Comprehensive Report VI.16 Some credit information companies (CICs) were following the practice of offering limited versions of credit information reports (CIRs) to credit institutions (CIs) based on credit information available in specific modules such as commercial data, consumer data or micro finance institution (MFI) data and, as a result, lenders remained unaware of the complete credit history of borrowers available across various modules that affected the quality of their credit decisions. Further, CICs were charging differential rates for such specific reports. CICs were, therefore, directed to ensure that the CIR in respect of a borrower furnished to the CI, incorporated all the credit information available in all modules in respect of the borrower. Harmonised Definitions across Returns Released VI.17 Based on the recommendations of the Inter-Departmental Task Force constituted in December 2014, definitions of 189 data elements reported to the Reserve Bank across multiple banking and regulatory returns were harmonised. Aligning Prudential Norms for Category I and II Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs)1 VI.18 Banks had general permission to invest up to 10 per cent of unit capital of an AIF-I, beyond which they needed prior approval of the Reserve Bank. Investments in AIF-II were approved on a case to case basis. As AIFs-I and AIFs-II do not undertake leverage or borrowing other than to meet day-to-day operational requirements, it was decided in September 2017 to align the norms for banks’ investment in AIF-I and AIF-II, allowing banks to invest up to 10 per cent of the unit capital of an AIF-I/AIF-II beyond which they will require prior approval of the Reserve Bank. Prohibiting Investment in Category III AIFs VI.19 Investments by banks in AIFs-III have been specifically prohibited. Further, with a view to restricting indirect exposure of banks, a ceiling has been prescribed on investment by banks’ subsidiaries in AIFs-III, i.e., up to the regulatory minima prescribed by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) on sponsor/ manager commitment (5 per cent of the corpus or ₹100 million, whichever is less). Capital towards Reputational Risk VI.20 Banks have been advised in September 2017 to ascertain the reputational risk owing to association of name of the bank with AIFs/ Infrastructure Debt Funds (IDFs) within the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) framework and determine the additional capital required, which will be subject to supervisory examination as part of the supervisory review and evaluation process. Alignment with BASEL III Capital Requirements VI.21 In September 2017, the minimum capital requirement for banks’ to invest in financial services companies and other specified investments/activities was increased from CRAR of 10 per cent to the minimum CRAR plus the capital conservation buffer (CCB), thus aligning the minimum CRAR requirement with the CCB requirement under the Basel III framework. Banks to Act as Professional Clearing Member of Commodities Derivative Market VI.22 In September 2017, banks were allowed to become professional clearing members of commodity derivatives segment of SEBI registered exchanges, subject to their compliance with the extant prudential parameters for membership of stock exchanges [minimum net worth of ₹5 billion, maintenance of minimum prescribed capital (including Capital Conservation Buffer), net NPA ratio of not more than 3 per cent and profitability in last three years]. However, they cannot take proprietary positions in commodity derivatives. Banks’ Subsidiaries to Undertake Broking in Commodities Derivative Market VI.23 As banks’ broking subsidiaries bring a lot of value by their operation in the stock market, especially in enabling retail participation in the capital markets, allowing banks’ broking subsidiaries in commodity derivatives segment would help them reach out to the retail participants and untapped customer segments. Accordingly, banks’ subsidiaries have been allowed to offer broking services in the commodity derivatives segment of the exchanges subject to not undertaking proprietary positions in this segment. FinTech and Regulatory Initiatives VI.24 The Reserve Bank had set up an inter-regulatory Working Group on FinTech and Digital Banking to look into the granular aspects of FinTech and its implications so as to review and reorient appropriately the regulatory framework and respond to the dynamics of the rapidly evolving FinTech scenario. The report of the Working Group was released on February 08, 2018 for public comments. One of the key recommendations of the Working Group was to introduce a framework for “regulatory sandbox/ innovation hub” within a well-defined space and duration where the financial sector regulator would provide the requisite regulatory guidance, so as to increase efficiency, manage risks and create new opportunities for the consumers in the Indian context similar to other regulatory jurisdictions (Box VI.3). Box VI.3

FinTech Regulatory Sandbox- Objectives, Principles, Benefits and Risks The highlights of the FinTech Regulatory Sandbox are as follows: i. The regulatory sandbox–need and purpose A regulatory sandbox refers to live testing of new products or services in a controlled/test regulatory environment. Regulatory and supervisory authorities may have an active role to play in sandbox arrangements as they may permit certain regulatory/supervisory relaxations to the entities testing their products in the sandbox. ii. Benefits of regulatory sandbox Users of a sandbox can test the product’s viability without the need for a larger and more expensive roll out. The sandbox could lead to better outcomes for consumers through an increased range of products and services, reduced costs, and improved access to financial services. iii. Risk and limitations The major challenges of the regulatory sandbox are the issues arising out of customer and data protection. Design aspects of regulatory sandboxes When considering establishing a sandbox, regulators may look into the following key design features: 1. Number of FinTech entities to be part of a cohort: The sandbox may run a few cohorts (end to end sandboxing process) of which each cohort may accept a limited number of entities for testing their products during a specific period. 2. Eligibility conditions for sandbox: The applicants for the sandbox may include existing financial institutions and FinTech firms. 3. Boundary conditions: The boundary conditions for the sandbox may include start and end date of the sandbox; target customer type; limit on the number of customers involved; other quantifiable limits such as transaction thresholds or cash holding limits, where applicable; and volume of business. 4. Exit plan: An acceptable exit and transition strategy should be clearly defined in the event of discontinuation of the proposed financial service or can proceed to be deployed on a broader scale after exiting the sandbox. 5. Criteria for joining the sandbox: The technological innovation in financial services that brings benefits to consumers is the main criteria for joining the sandbox. 6. Criteria for evaluation: The proposed financial service should be innovative and should have the intention and ability to deploy the proposed financial service in India. 7. Consumer protection: The sandbox entity should ensure that any existing obligation (including data privacy) to its customers is fully addressed before exiting the sandbox. | Submission of Financial Information to Information Utilities VI.25 According to Section 215 of the IBC, 2016, a financial creditor shall submit financial information and information relating to assets in relation to which any security interest has been created, to an information utility (IU) in such form and manner as may be specified in Chapter V of the IBBI (Information Utilities) Regulations, 2017. In December 2017, all financial creditors regulated by the Reserve Bank were advised to adhere to the relevant provisions of IBC, 2016 and IBBI (IUs) Regulations, 2017 and immediately put in place appropriate systems and procedures to ensure compliance with these provisions. Prohibition on Dealing in Virtual Currencies VI.26 The Reserve Bank, through its public notices, has repeatedly cautioned users, holders and traders of virtual currencies (VCs), including bitcoins, regarding the risks associated with dealing with such currencies. In view of the associated risks, the Reserve Bank mandated in April 2018 that the entities regulated by it should not deal in VCs or provide services for facilitating any person or entity in dealing with or settling VCs. Further, regulated entities which already provide such services should exit the relationship within three months. Update on KYC Direction, 2016 VI.27 To align with the amendments in the Prevention of Money Laundering (PML) Rules by the government, amendments to the Master Direction on KYC have been issued. Aadhaar Number has been made mandatory (for those individuals who are eligible to be enrolled for Aadhaar) along with PAN/Form 60 for all account based relationships. Enrolment number for Aadhaar is admissible if not older than 6 months; however, the Aadhaar Number has to be provided within the next 6 months. Definition of Officially Valid Documents (OVDs) has been amended. With the designation of Aadhaar number and PAN number as mandatory documents, the OVDs are (i) passport, (ii) driving licence, (iii) voter’s identity card, (iv) NREGA job card duly signed by an officer of the state government and (v) letter issued by the National Population Register containing details of name and address. Aadhaar number will have to be authenticated by the reporting entities using e-KYC authentication [biometric or One Time Password (OTP) based] or yes/no authentication. The above instructions are subject to the final judgment of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Anr. V. Union of India, W.P. (Civil) 494/2012 etc. (Aadhaar cases). VI.28 Where current address is not available in Aadhaar card, an OVD has to be furnished giving the current address. To address immediate concerns, a time window of 3 months has been provided within which alternate documents like utility bills not older than 2 months, can be temporarily used as a proof of current address. Further, the process of certification has been codified, requiring comparing of the copy of OVD so produced by the client with the original and recording the same on the copy by the authorised officer of the reporting entity. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.29 The Reserve Bank will continue to focus on those action points pertaining to 2017-18, which remain work-in-progress, viz., Ind AS implementation, issuance of final guidelines on variation margin requirements, revised framework for securitization and guidelines on corporate governance in line with the evolving Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) standards. BCBS has deferred the implementation of the revised market framework to January 1, 2022. Accordingly, the work on minimum capital requirements for market risk will not be pursued during 2018-19. VI.30 The Reserve Bank will issue revised prudential regulations, covering instructions on exposure norms, investment norms, risk management framework and select elements of Basel III capital framework to the All India Financial Institutions (AIFIs). VI.31 There are significant differences in the corporate structure permissible to banks for setting up financial services entities, depending upon the timing of their licensing. It is, therefore, proposed to harmonise these differences under a common set of guidelines. VI.32 With a view to promoting innovation in financial services, it is proposed to enter into collaborative arrangements with other leading regulators in this area. VI.33 For the purpose of fostering competition and re-orienting the banking structure in India, the policy on subsidiarisation of foreign banks and the Marginal Cost of Funds Based Lending Rate (MCLR) guidelines will be reviewed. VI.34 The regulatory guidelines for regional rural banks (RRBs) vis-à-vis SCBs will be reviewed. Cooperative Banks: Department of Cooperative Bank Regulation (DCBR) VI.35 As cooperative banks play an important role in the Indian financial system, the Reserve Bank has always endeavoured to strengthen the regulatory and supervisory framework so that they emerge financially strong and have sound governance. In this context, DCBR, in charge of prudential regulations of cooperative banks, took the following initiatives in 2017-18. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status Harmonisation of Regulatory Policies VI.36 The harmonisation of regulatory policies for all cooperative banks is an ongoing process. As part of this, the regulatory process for opening of current account with the Reserve Bank has been simplified for all the cooperative banks [urban cooperative banks (UCBs), state cooperative banks (StCBs) and district central cooperative banks (DCCBs)]. The guidelines on limiting liability of customers on account of unauthorised electronic banking transactions have been extended to all cooperative banks. The guidelines on lending to priority sector have been harmonised with those of SCBs. Revival and Licensing of Unlicensed DCCBs VI.37 On the three unlicensed DCCBs in the state of Jammu & Kashmir, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by the state, the Government of India and NABARD. Accordingly, the state government has released its share of ₹2.56 billion in March 2018 and the same is held with the cooperative department of Jammu and Kashmir government for onward transmission to the three DCCBs. Issue of licences to these three DCCBs will be considered after the funds are transferred to them by the state government. Review of Supervisory Action Framework for UCBs VI.38 The review of supervisory action framework for urban cooperative banks is under process. The trigger points for initiating corrective action are being reviewed to help ensure that the weak UCBs are turned around well in time. This agenda is carried forward to the year 2018-19. CBS under the Scheme of Financial Assistance to UCBs VI.39 A scheme of financial assistance to UCBs for implementing the core banking solution (CBS) was announced on April 13, 2016 in consultation with the Institute for Development and Research in Banking Technology (IDRBT) and the Indian Financial Technology and Allied Services (IFTAS) (a subsidiary of IDRBT). Under the scheme, the initial set up-cost of ₹0.4 million has been paid by the Reserve Bank to IFTAS. During the year, 3 more UCBs implemented CBS under the scheme, taking the number of CBS-compliant UCBs to 1,453. Formulation of Standards and Benchmarks for CBS in UCBs VI.40 A document on functional and technical requirements for CBS in UCBs prepared by IDRBT in consultation with the Reserve Bank was released in July 2017. Scheduling, Licensing, Mergers and Voluntary Conversions VI.41 Six proposals for merger were received. Of these, five were granted permission, including two cases of merger of banks having negative net worth with stronger UCBs. The remaining proposal, received in June 2018, is presently under process. Two mergers took place during the year. Further, one UCB voluntarily converted itself into a (non-banking) cooperative credit society under Section 36A (2) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.42 The agenda for 2018-19 includes issuing of licenses to the three unlicensed DCCBs in Jammu and Kashmir in pursuance of the objective that only licensed rural cooperative banks operate in the banking space. DCBR will reinforce the agenda to ensure that rural cooperative banks are adequately capitalized to meet any challenges and mitigate risks arising due to changes in the banking scenario. The supervisory action framework for UCBs, framed in 2014, will be reviewed in order to engage with the concerned banks at an early stage for corrective action. Implementation of CBS under the scheme of financial assistance to UCBs will continue during the year. The implementation of some of the recommendations of the High Powered Committee on UCBs (Chairman: Shri R Gandhi) is planned during the year. As recommended by the Committee, in order to improve governance in UCBs, it is proposed that UCBs shall constitute a Board of Management in addition to their elected Board. Draft guidelines in this regard have been issued for comments/feedback. A scheme on voluntary transition of eligible UCBs into Small Finance Banks (SFBs) as announced in the Second Bi-monthly Monetary Policy Statement for 2018-19, will also be issued during the year. Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs): Department of Non-Banking Regulation (DNBR) VI.43 NBFCs have evolved as an important alternate source of credit in the Indian economy. The Department of Non-Banking Regulation (DNBR) is entrusted with the responsibility of regulation of NBFCs. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status Peer to Peer Lending Platforms (NBFC-P2P) VI.44 The Reserve Bank issued the NBFC-P2P Directions in October 2017. While the online platform itself does not undertake any financial activity, it provides a platform for credit intermediation, bringing together borrowers and lenders. Regulations have been framed to ensure customer protection, data security and orderly growth. Outsourcing Guidelines for NBFCs VI.45 With the objective of bringing the outsourced activities of NBFCs within the regulatory purview as well as ensuring sound and responsive risk management practices by NBFCs, the Reserve Bank issued directions to NBFCs on managing risks arising from outsourcing activities associated with financial services provided by them. Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) VI.46 ARCs complying with corporate governance practices, have been exempted from the shareholding limit of 26 per cent of post converted equity of the borrower company if the extent of shareholding after the conversion of debt to equity does not exceed the permissible foreign direct investment (FDI) limit for the specific sector. To expand the investor base and to infuse greater depth in the Security Receipt (SR) market, the Reserve Bank has notified Alternative Investment Fund category II and III, registered with SEBI as non-institutional investors. Prudential Regulation of Government NBFCs VI.47 Government-NBFCs cater to various social obligations and, in the process, their over-exposure to certain sectors may have adverse financial implications depending upon the scale of operations. Further, as entities raising public funds, they have high level of interconnectedness with the formal financial sector. In order to strengthen and ensure ownership-neutral regulations, government-owned NBFCs will now be required to adhere to the Bank’s prudential regulations in a phased manner (Box VI.4). Other Initiatives VI.48 Systemically Important Non-Deposit taking Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFC-ND- SIs) have been allowed to undertake Point of Presence (PoP) services for National Pension Scheme (NPS), subject to certain conditions. VI.49 In order to promote investments in infrastructure by Systemically Important Core Investment Companies (CIC-ND-SI), CIC-ND-SIs have been permitted to hold Infrastructure Investment Funds (InvIT) units only as sponsors provided such exposure does not exceed the minimum holding and tenor limits as prescribed under SEBI regulations for a sponsor. These holdings will be reckoned as investments in equity shares in group companies, for the purpose of compliance with the norms for investment in group companies applicable to CIC-ND-SI. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.50 As per the Ministry of Corporate Affairs notification, NBFCs/Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) with a net worth of ₹5 billion and above are required to implement Ind AS with effect from April 1, 2018. VI.51 With a view to strengthening the ARCs, the Reserve Bank will issue guidelines on ‘fit and proper criteria’ for their sponsors. VI.52 The Reserve Bank is planning to extend the harmonised and simplified generic framework for resolution of stressed assets put in place for banks to NBFCs as well. Box VI.4

Regulatory Framework for Government-Owned NBFCs There are currently 42 government-owned NBFCs registered with the Reserve Bank. Of these, 16 are owned by the central government and 26 by the state governments. Of these government NBFCs, 23 NBFCs are classified as non-deposit taking systematically important NBFCs (NBFC-ND-SI), 12 are non-deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-ND) and 7 are deposit taking NBFCs (NBFC-D). Government owned NBFCs have been, till now, exempted from various provisions of the RBI Act, 1934 as well as prudential norms since they cater to various social obligations. However, it is recognised that their high exposure to certain sectors may have adverse financial stability implications, especially where the scale of operations is large. Further, as entities raising public funds, they have high level of interconnectedness with the formal financial sector. Accordingly, deposit taking and systemically important government-owned NBFCs were advised in 2006 to submit a roadmap for complying with the prudential regulations applicable to other NBFCs. Although all central government NBFCs and 12 state government NBFCs submitted their road map, their implementation has been disparate. Hence, it was decided to require government-owned NBFCs vide notification dated May 31, 2018 to adhere to the Bank’s prudential regulations, and instructions on acceptance of public deposits, corporate governance, conduct of business regulations and statutory provisions, in a phased manner. A phase-in period till 2022 has been prescribed to ensure that the withdrawal of exemptions takes place in a non-disruptive manner. | VI.53 The transition of government-NBFCs to the prudential regulations will be closely monitored. VI.54 The Reserve Bank has been aligning its policies to the changing dynamics in FinTech sector and has already issued guidelines for two new types of IT based NBFCs, viz., NBFC-Account Aggregator (NBFC-AA) and NBFC-Peer to Peer (NBFC-P2P). During the year, the Bank will examine applications from companies which propose to conduct NBFC business through virtual modes, without a brick and mortar presence. SUPERVISION OF FINANCIAL INTERMEDIARIES Department of Banking Supervision (DBS) VI.55 In India’s bank dominated financial system, DBS, entrusted with the responsibility of supervising SCBs (excluding RRBs), plays a central role in ensuring systemic stability. DBS also supervises Local Area Banks (LABs), Payments Banks (PBs), Small Finance Banks (SFBs), Credit Information Companies (CICs) and All India Financial Institutions (AIFIs) within the existing statutory and regulatory framework. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status VI.56 Risk-Based Supervision (RBS) under the Supervisory Programme for Assessment of Risk and Capital (SPARC) for banks operating in India has been successfully implemented over five supervisory cycles. The development of supervisory framework for SFBs and PBs is currently underway. During the year, the RBS model was subjected to an external validation. As part of the process for sensitising the top management of banks about SPARC, interactive sessions were conducted for board members and top management of several public and private sector banks during the year. Focused workshops were also convened for skill enhancement of operational as well as senior/middle level management of these banks. VI.57 During 2017-18, supervisory assessments of 76 SCBs, 1 LAB and 2 CICs were placed before the Board of Financial Supervision (BFS). VI.58 Thirty five Information technology (IT) examinations covering broad spectrum of IT risk and thematic examinations of specific focus areas were carried out during the year to evaluate cyber security readiness of the banking sector. Mock cyber-drills involving hypothetical scenarios were conducted to evaluate the cyber security incident response preparedness of banks. The exercise helped banks identify and rectify deficiencies in their incident management capabilities. The Reserve Bank, in pursuance of a fraud involving Letters of Undertaking (LoU) reported by banks, had assessed the operational controls around Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) transactions and advised banks to strengthen the same. It was observed that the action taken by banks in protecting the systems was not adequate and hence the Reserve Bank reiterated its instructions with clear timelines for implementation by banks. Trend Analysis on Frauds VI.59 The number of cases on frauds reported by banks were generally hovering at around 4500 in the last 10 years before their increase to 5835 in 2017-18 (Chart VI.1a). Similarly, the amount involved in frauds was increasing gradually, followed by a significant increase in 2017-18 to ₹410 billion (Chart VI.1b). The quantum jump in the amount involved in frauds during 2017-18 was on account of a large value fraud committed in gems and jewellery sector, mainly affecting one public sector bank (PSB).  VI.60 During 2017-18, PSBs accounted for 92.9 per cent of the amount involved in frauds of more than ₹0.1 million, as reported to the Reserve Bank while the private sector banks accounted for 6 per cent. As regards cumulative amount involved in frauds till March 31, 2018, PSBs accounted for around 85 per cent, while the private sector banks accounted for a little over 10 per cent. At the system level, frauds in loans, by amount, accounted for more than 75 per cent of frauds involving amounts of ₹0.1 million and above while frauds in deposit accounts were at just over 3 per cent (Chart VI.2). Within the loan category of frauds, PSBs accounted for a major share (87 per cent) followed by the private sector banks (11 per cent). The share of PSBs in frauds relating to ‘off-balance sheet items’ such as Letter of Credit (LCs), LoU, and Letter of Acceptance was even higher at 96 per cent. New private sector banks accounted for more than 20 per cent of the frauds related to ‘cash/cheques/clearing’ and ‘foreign exchange transactions’. New private sector and foreign banks accounted for 36 per cent each of all cyber frauds reported in debit, credit and ATM cards, among others. Out of the seven classifications of frauds in alignment with the Indian Penal Code, ‘cheating and forgery’ was the major component followed by ‘misappropriation and criminal breach of trust’. In ‘cheating and forgery’ cases, the most common modus operandi was multiple mortgage and forged documents. Mumbai (Greater Mumbai), Kolkata and Delhi were the top three cities in reporting of bank frauds through ‘cheating and forgery’. In respect of staff involvement in frauds, banks reported that it was prominent in the categories ‘cash’ and ‘deposits’, which had a much smaller share in the overall number of fraud incidents and the amount involved. One of the major initiatives in recent times in fraud mitigation was the introduction of a Central Fraud Registry (CFR), a web-based online searchable database of reported frauds, for the use of banks.  Agenda for 2018-19 VI.61 In view of large divergences observed in asset classification and provisioning in the credit portfolio of banks as well as the rising incidence of frauds in the Indian banking system, an Expert Committee under the chairmanship of Shri Y.H. Malegam, a former member of the Central Board of the Reserve Bank, had been constituted to look into the reasons for high divergence observed in asset classification and provisioning by banks vis-à-vis the Reserve Bank’s supervisory assessment, and the steps needed to prevent it; factors leading to an increasing incidence of frauds in banks and the measures (including IT interventions) needed to curb and prevent it; and the role and effectiveness of various types of audits conducted in banks in mitigating the incidence of such divergence and frauds. The recommendations of the committee will be carried forward for implementation. VI.62 It was proposed to initiate network analysis for the financial conglomerate (FC) groups to assess the systemic risks posed by them. The analysis would cover the major entities of an FC group in each financial market segment and intra-group exposures would also be considered. The findings would be shared with the regulators and significant trends and/or concerns would be discussed in the meetings of the Inter-Regulatory Forum (IRF). VI.63 In line with the evolution of regulatory guidelines on the implementation of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)/Ind AS, the impact on quantitative and qualitative reporting by banks would be reviewed, aligned and integrated with the supervisory framework. Specific sensitisation sessions for the top management of SFBs and PBs in respect of the supervisory framework for these banks are on the agenda for 2018-19. VI.64 In an endeavour to strengthen the cyber security posture of Indian banks, focused and theme-based IT examinations are planned during 2018-19. Targeted scrutiny, as and when required, would also be conducted for appropriate policy and supervisory intervention. VI.65 In order to secure consistency and improve the efficiency of the offsite monitoring mechanism, an Audit Management Application portal to facilitate various supervisory functions of the Cyber Security and Information Technology Examination (CSITE) Cell and to fully automate monitoring of returns has been envisaged, which will be operationalised by March 2019. Further, there is an urgent need to strengthen the existing audit systems of banks and align them with the prevailing global best practices (Box VI.5). Cooperative Banks: Department of Cooperative Bank Supervision (DCBS) VI.66 The primary responsibility of DCBS is supervising primary (urban) cooperative banks (UCBs) while also ensuring the development of a safe and well-managed cooperative banking sector. Towards this objective, DCBS undertakes supervision of UCBs through periodic on-site and continuous off-site monitoring. As at end-June 2018, 1,550 UCBs were operating in the country, out of which 39 UCBs had negative net worth and 20 UCBs were under directions of the Reserve Bank. Box VI.5

Improving Audit Systems in Banks SCBs undertake various types of audit such as statutory audit, risk based internal audit (RBIA), concurrent audit, information systems (IS) audit and special audits. Major fraud incidents reported by banks in the recent past have highlighted the need for improvement in the audit function and its governance. In addition, an increase in divergence in asset classification and provisioning as assessed by the Reserve Bank vis-à-vis the audited financial statements of SCBs has been seen as a concern. Role of Audit Committee of Boards (ACBs): ACBs are mandated to provide direction, as also oversee the operation of the total audit function in SCBs. Apart from reviewing routine items of interest, ACBs are to oversee benchmarking of banks’ systems and processes on a continuous basis so as to ensure strict adherence to internal guidelines as well as various regulatory norms. Concurrent Audit: Concurrent audit has to be carried out on a real time or near real time basis and is expected to set the tone for subsequent internal audit which happens with a time lag. Exception reports, even of a routine nature, are to be seen in detail on an ongoing basis. Audit trail should be checked for diversion of funds through round tripping and other means. Further, the auditor needs to ensure that FEMA guidelines are complied with and KYC / AML directions are implemented properly. Internal Audit: A strong internal control system, including an independent and effective internal audit function, is a part of sound corporate governance. The quality of internal audit was adversely affected due to inadequate human resources, lack of desired skill-sets (particularly for specialised branches), non-adherence to stipulated timelines for compliance with audit findings, non-inclusion of some critical areas, etc., indicating inadequate attention to sustainable compliance with the findings of earlier reports. Many instances of repetitive and similar audit findings over the years were seen. Further, internal audit could not detect many frauds, which came to light after accounts turned NPA. Fraud detection and reporting, as well as preventive steps, need to be more risk-focused so as to identify red flags at an incipient stage. Non-adherence to Income Recognition and Asset Classification (IRAC) norms by banks is a major concern. In this respect, audit function still needs to provide desired level of assurance to all stakeholders, including the Reserve Bank. While there may be instances of information asymmetry between the supervisor and other stakeholders, NPA divergence should not arise from lack of adherence to regulatory guidelines. Statutory Audit: Statutory auditors need to undertake root cause analysis to identify deficiencies exposed by incidents of fraud, and divergences in asset classification and provisioning. Statutory auditors could identify issues faced by banks in implementing system-based identification of NPAs as well as utilise more effectively the central database in banks for their assignments. Further, inputs provided by statutory auditors through Long Form Audit Report need to be improved, since they provide useful inputs for risk based supervision of banks. Enforcement Action Framework for Statutory Auditors (SAs): In the interest of improving audit quality and the need to institute a transparent mechanism to examine the accountability of SAs in a consistent manner, it has been decided to put in place a graded enforcement action framework to enable appropriate action by the Reserve Bank in respect of the banks’ SAs for any lapses observed in conducting a bank’s statutory audit. This would cover, inter alia, instances of divergence identified in asset classification and provisioning during the Reserve Bank’s inspection vis-à-vis the audited financial statements of banks above the threshold specified by the Reserve Bank in the circular issued on April 18, 2017. | Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status Enhanced Focus on Capacity Building VI.67 During the year, additional emphasis was laid on the training needs of the workforce in the UCBs including the employees, management and the auditors. As the UCBs are geographically spread across the country, the regional offices of the Reserve Bank were assigned the crucial role of closely interacting with them and nurturing them. The regional offices developed training modules to cater exclusively to the staff of UCBs. Also, in view of the importance of corporate governance and the role of efficient management, a separate training was conducted for the chief executive officers (CEOs) and the board members of the UCBs. As the auditors are the extended arm of a supervisor, they were also periodically covered separately by means of dedicated training sessions. Apart from this, weak banks were identified based on outcome of either on-site inspection or off-site monitoring and specific hand holding programmes were arranged to focus on those areas that required improvement in the concerned banks. Stabilisation of XBRL Platform VI.68 The XBRL platform enables standardisation and rationalisation of elements of different returns sent by banks using the internationally recognised best practices available in electronic transmission. On rationalising the returns submitted, UCBs now submit only 22 returns that comprise of statutory, regulatory and supervisory data and information. A return on reporting the fraud data is in the final stage of submission on the XBRL platform. Agenda for 2018-19 To Review Inspection Process with Focus on Timely Completion VI.69 The heterogeneity of the sector coupled with the large number of UCBs poses a challenge in optimal allocation of supervisory resources. In order to overcome this challenge, innovative methodologies were adopted to achieve a proper balance between resources used and supervisory outputs. To further smoothen the process and ensure qualitative reports on an ongoing basis, the supervisory process would be further fine-tuned to enhance its efficacy and effectiveness. NBFCs: Department of Non-Banking Supervision (DNBS) VI.70 DNBS supervises 11,174 NBFCs of which 249 are NBFC-Non Deposit taking Systemically Important ones. During the year, NBFC sector witnessed higher asset growth. Two new types of NBFCs, viz., Account Aggregators and P2P lending platforms have been allowed to operate, which added to the diversity of the sector. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status VI.71 The ‘Sachet’ portal for NBFCs has been refurbished for improved user interface and functionalities. The new version will be operationalised once the translation into regional languages is complete. A supervisory rating framework for ARCs has been devised by the Bank and since been operationalised from the inspection cycle 2018-19. The Reserve Bank has initiated supervisory action against those NBFCs which are non-compliant, inactive and not meeting the minimum net owned fund (NOF) criteria, thereby tightening the supervisory regime. During the last round of inspections, the risk-focused model was tried out in parallel to the existing inspection report format and the same has been finalised and is being implemented from the current inspection cycle 2018-19. The number of supervisory returns under XBRL format has been rationalised to avoid duplication of data as also to capture granular sectoral credit data and financial aspects of interconnectedness. The modified returns being developed in XBRL are currently in testing phase. The on-site inspection and off-site surveillance framework has also been extended to government-owned NBFCs and supervisory returns with effect from the quarter ending December, 2017 are being called for. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.72 The government-owned NBFCs will be subjected to on-site inspection from the inspection cycle 2018-19. Supervisory returns for NBFC-Account Aggregators and NBFC-P2P lending platform will be developed. An on-line portal for reporting of cyber security incidents of NBFCs will be put in place. Enforcement Department (EFD) VI.73 The EFD started functioning since April 2017. The core function of the department is to enforce regulation with an objective to ensure financial system stability, greater public interest and consumer protection. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status VI.74 During the year, an enforcement policy and framework was put in place for taking enforcement action in an objective, consistent and non-partisan manner. EFD also devised a protocol for sharing information within the Bank and initiated enforcement action with regard to commercial banks. VI.75 During July 2017 to June 2018, EFD undertook enforcement action against 14 banks (including a PB and an SFB, and imposed an aggregate penalty of ₹1,024 million, for non-compliance/contravention of regulatory restrictions on loans and advances, violation of licensing conditions and operating guidelines for SFBs and PBs, violations of KYC norms, violations of Income Recognition and Asset Classification (IRAC) norms, delay in reporting of information security incidents as also for non compliance with norms relating to extending bill discounting and non-fund based facilities, detection and impounding of counterfeit notes and issue of bonus shares by private sector banks and for not adhering to specific directions issued on direct sale of securities from held to maturity (HTM) portfolio, among others. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.76 Going forward, the enforcement work pertaining to UCBs and NBFCs is being brought under the EFD in a phased manner. CONSUMER EDUCATION AND PROTECTION Consumer Education and Protection Department (CEPD) VI.77 The mandate of CEPD is to monitor and ensure protection of interests of consumers of the regulated entities and maintain oversight on the administration and functioning of the Banking Ombudsman (BO) scheme. Agenda for 2017-18: Implementation Status VI.78 The Reserve Bank implemented the Ombudsman Scheme for NBFCs with effect from February 23, 2018, which, to begin with, covered all deposit taking NBFCs. The offices of NBFC Ombudsman have started functioning from four metro centres - Chennai, Kolkata, Mumbai and New Delhi and each office handles the complaints of customers of NBFCs from the respective zone. VI.79 The BO scheme was reviewed and updated to include mis-selling and complaints relating to internet and mobile banking as valid grounds of complaints and the modification in BO scheme came into effect from July 1, 2017. The restriction on pecuniary jurisdiction of the BO in passing an Award was removed and the amount of compensation that the BO can sanction was doubled to ₹2 million. As a measure to enhance the accountability of banks, additional compensation up to ₹0.1 million for harassment/mental agony, earlier available only for credit/debit card related complaints, has been extended to all types of complaints covered under the scheme. VI.80 In order to assess the nature of mis-selling and the charges levied by banks for basic banking services, a study was conducted. In addition, a study on KYC compliance by banks was done with a view to enhancing the security of all genuine customers. VI.81 Consumer education has been a continuous endeavour of the Reserve Bank and during 2017-18, the SMS handle of the Reserve Bank, viz., RBISAY was used for spreading awareness about fictitious offers and the caution with which electronic banking facilities should be used. Further, during the year, all the offices of BOs conducted awareness programmes, mainly in Tier II cities. Agenda for 2018-19 VI.82 As part of the Reserve Bank’s initiative to improve the efficacy of grievance redressal mechanism in view of the rising number of complaints, an online Complaint Management System (CMS) assumes importance. Accordingly, the process for development of an online dispute resolution mechanism for customers of banks and eligible NBFCs has started and will be completed in 2018-19. VI.83 The increasing volume of complaints involving digital payments being received by the offices of BOs and the large number of Prepaid Payment Instruments (PPIs) issued by banks and non-bank issuers have necessitated the establishment of a separate Ombudsman for digital transactions. The Reserve Bank will formulate an Ombudsman Scheme for digital transactions and will set up offices of Ombudsman for digital transactions at select centres. It will also review the Ombudsman Scheme for NBFCs for enhancing its coverage to other eligible NBFCs during the year (Box VI.6). Box VI.6

Ombudsman Scheme for Bank Customers – A Perspective Ombudsman as alternative disputes resolution mechanism Ombudsman schemes in the financial sector, particularly in banking, is seen as the mainstay of grievance redressal for customers. The organisation and funding of this alternative forum of dispute resolution varies across jurisdictions. The Financial Ombudsman Scheme of the UK as also of Australia, Banking Ombudsman scheme of New Zealand and Ombudsman for Banking Services and Investments of Canada are funded by the industry while the Financial Industry Disputes Redressal Centre of Singapore charges fee from both parties to the dispute, i.e., the complainant as well as the financial institution concerned. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau of the USA is supported by the Federal Reserve System. Distinctive features of banking ombudsman scheme In India, the Banking Ombudsman (BO) scheme is the flagship consumer protection initiative which functions under the aegis of the Reserve Bank and as such does not rely on customer or industry body for carrying out its operations. With the involvement of the central bank, the BO scheme provides a cost free and expeditious grievance redressal mechanism to customers of banks. The BO also plays an active role in spreading awareness and imparting education on financial transactions as well as on the avenue available for grievance redressal. In order to keep pace with the changing landscape of financial transactions, the BO scheme has been revised five times since its launch in 1995. Keeping in view the experience of running this scheme for customers of banks, the Reserve Bank in 2018 also implemented the Ombudsman Scheme for NBFCs. Way Forward The grievances relating to digital mode of financial transactions accounted for 19 per cent of total complaints during 2016-17. This has gone up to 28 per cent till end- June 2018, particularly with the inclusion of deficiencies in mobile banking service as a ground of complaint under the scheme with effect from July 1, 2017. Although a separate Ombudsman Scheme for complaints relating to digital financial transactions is not existing in other major jurisdictions, the growing trend and increasing complexity of such complaints along with the emergence of non-bank service providers in the digital payment space underlines the need for designing a dedicated Ombudsman Scheme for redressal of such grievances. | Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC) VI.84 The deposit insurance system as one of the important pillars of financial safety net provides confidence to depositors and thereby promotes financial stability. Deposit insurance extended by DICGC covers all commercial banks including LABs, PBs, SFBs, RRBs and cooperative banks. The number of registered insured banks as on March 31, 2018 stood at 2,109, comprising 160 commercial banks (including 56 RRBs, 3 LABs, 5 PBs and 10 SFBs) and 1,949 cooperative banks (33 StCBs, 364 DCCBs and 1,552 UCBs). With the present limit of deposit insurance in India at ₹0.1 million, the number of fully protected accounts (1,898 million) as at end-March 2018 constituted 92 per cent of the total number of accounts (2,063 million) as against the international benchmark2 of 80 per cent. In terms of amount, the total insured deposits of ₹33,135 billion as at end-March 2018 constituted 28 per cent of assessable deposits amounting at ₹118,279 billion as against the international benchmark of 20 to 30 per cent. At the current level, the insurance cover works out to 0.9 times per capita income for 2017-18. VI.85 DICGC builds up its Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) through transfer of its surplus, i.e., excess of income (mainly comprising premia received from insured banks, interest income from investments and cash recovery out of assets of failed banks) over expenditure (payment of claims of depositors and related expenses) each year, net of taxes. This fund is available for settlement of claims of depositors of banks taken into liquidation/amalgamation. During 2017-18, the Corporation sanctioned total claims of ₹0.4 billion as against claims aggregating ₹0.6 billion during the preceding year. The size of the DIF stood at ₹814.3 billion as on March 31, 2018, resulting in a reserve ratio (DIF/Insured Deposits) of 2.5 per cent. VI.86 The Key Attributes (KAs) of effective resolution regimes for financial institutions issued by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) postulate that the objective of an effective resolution regime is to make feasible the resolution of financial institutions without severe systemic disruption and without exposing taxpayers to loss. The resolution regime should also protect vital economic functions through mechanisms which facilitates shareholders and unsecured and uninsured creditors to absorb losses in a manner that respects the hierarchy of claims in liquidation. The bail-in is designed as one of the tools for resolution of financial entities (Box VI.7). National Housing Bank (NHB) VI.87 NHB was set up on July 9, 1988, under the National Housing Bank Act, 1987, as an apex institution for housing finance. The primary function of NHB is to register, regulate and supervise the housing finance companies (HFCs). The entire capital of ₹14.5 billion of NHB is subscribed by the Reserve Bank. As on June 30, 2018, 96 HFCs were registered with NHB, out of which 18 HFCs were eligible to accept public deposits. VI.88 NHB also provides refinance to HFCs, SCBs, RRBs and co-operative credit institutions for housing loans and also undertakes direct lending (project finance) to borrowers in the public and private sector. Over the years, NHB’s focus area has been to provide financial support to the housing programmes for unserved and underserved segments of the population. Out of the total disbursement of ₹249.20 billion made under refinance in 2017-18 (July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018), 8.08 per cent (₹18.28 billion) was made under the Rural Housing Fund (RHF). As a nodal agency to implement the Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS) under the “Housing for All by 2022” mission of the government, NHB released subsidy claims of ₹42.85 billion to 138 Primary Lending Institutions (PLIs) till June 30, 2018 (since inception), benefitting 1,96,543 households. Box VI.7

Bail-in as a Resolution Tool of Financial Institutions: International Best Practices In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, comprehensive measures relating to resolution of failing financial institutions were undertaken by the US and the European Union (EU). In 2010, the US established a resolution framework for systemic financial institutions under the Dodd-Frank Act. All member states in EU were required to transpose the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) into their national law from January 2015. A key element of the new process is the bail-in tool, requiring banks to recapitalise and absorb losses from within, which was made mandatory as of January 1, 2016. The objective of bail-in, as a tool to resolve failing financial entities, is to ensure that the losses are absorbed by shareholders and creditors without having recourse to tax payers’ money or public funds. As per FSB’s KAs (FSB 2014, 2017), bail-in refers to powers of Resolution Authorities (i) to write down in a manner that respects the hierarchy of claims in liquidation, equity or other instruments of ownership of the firm, unsecured and uninsured creditor claims to the extent necessary to absorb the losses; (ii) to convert into equity or other instruments of ownership of the firm under resolution, all or parts of unsecured and uninsured creditor claims in a manner that respects the hierarchy of claims in liquidation; (iii) convert or write-down any contingent convertible or contractual bail-in instruments whose terms had not been triggered prior to entry into resolution and treat the resulting instruments in line with (i) or (ii). As per the European BRRD 2014, the main aim of bail-in is to stabilise a failing bank so that its essential services can continue, without the need for bail-out by public funds. The tool enables authorities to recapitalise a failing bank through the write-down of liabilities and/or their conversion into equity so that the bank can continue as a going concern. This would avoid disruption to the financial system that would otherwise occur as a result of stopping or interrupting the bank’s critical services and give the authorities time to reorganise the bank or wind down parts of its business in an orderly manner; recognised as an ‘open bank resolution’. In a ‘closed bank resolution’ the bank would be split into two, a good bank or bridge bank and a bad bank. The good bank or bridge bank is a newly created legal entity which continues to operate, while the bad bank is liquidated. As per the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR) and BRRD, the scope of bail-in tool can be applied to all liabilities that are not expressly excluded from the scope of bail-in. A key exclusion is for the covered deposits. The resolution authority (RA) may wholly or partially exclude certain liabilities from the bail-in in order to avoid widespread contagion that would disrupt the functioning of financial markets, in particular, deposits held by individuals and micro, small and medium enterprises. When applying the resolution tools, the RA would ensure that no creditor is worse off in resolution than under liquidation. As per the International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI) (2016), specialised tools like bail-in aimed at resolving systemic institutions should not be applied to small and medium sized institutions. Since the adoption of KAs of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions in November 2011, authorities in Crisis Management Groups constituted by FSB have been working to develop firm-specific resolution strategies and plans for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs). One of the challenges that emerged was the legal and operational complexity associated with the implementation of an effective bail-in transaction. While the KAs set out general powers that authorities should have for the purpose of bail-in within resolution, they do not consider the operational aspects. The FSB consultative document proposes a set of principles on the execution of bail-in to assist the work of authorities. The principles cover, inter alia, the range of actions and processes required to identify the instruments and liabilities within the scope of bail-in. Research underscores that the bail-in framework is still evolving and even with the limited experience so far, it is recognised that the bail-in tool poses some risks for Deposit Insurance Agencies (DIAs) (IADI 2015). The risks related to the use of DIA funds for bail-in arise from a change in the ownership pattern of banks after bail-in, the inappropriate use of funds, a costly resolution strategy from the DIA’s perspective, and threats to the credibility of the DIA if resolution funding and subsequent failure of the resolved institution deplete the deposit insurance fund. References: 1. European Commission (2014), “EU Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive: Frequently Asked Questions”, April. 2. Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2014), “Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions”, October. 3. Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2017), “Principles on Bail-in Execution”, Consultative Document, November. 4. International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI) (2015), “Deposit Insurance and Bail-in: Issues and Challenges”. 5. International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI) (2016), “A Handbook for the Assessment of Compliance with the Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems”, March. | VI.89 NHB is managing the Credit Risk Guarantee Fund Trust for Low Income Housing with the objective of providing guarantees in respect of low-income housing loans. As of June 30, 2018, 80 PLIs have signed MoU with the Trust under the Scheme. Till June 30, 2018, the Trust issued guarantee cover for 1977 loan accounts of 14 Member Lending Institutions (MLIs) involving a total loan amount of ₹562.40 million for economically weaker section/low income group households.

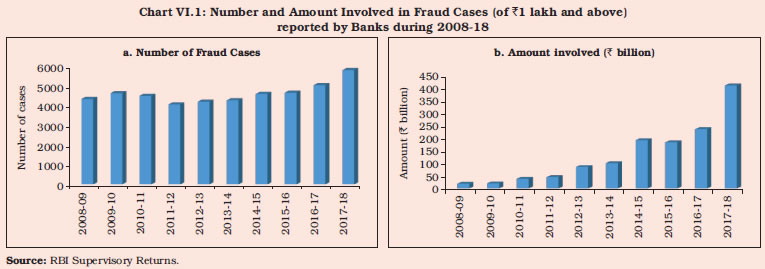

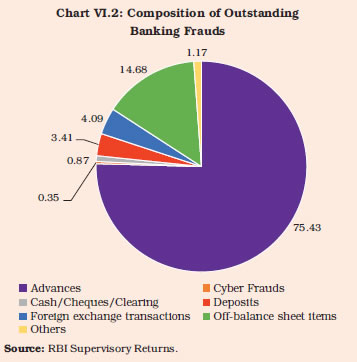

|