[Under Section 45ZL of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934]

The twenty fifth meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), constituted under section 45ZB of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, was held from October 7 to 9, 2020.

2. The meeting was attended by all the members – Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Senior Advisor, National Council of Applied Economic Research, Delhi; Dr. Ashima Goyal, Professor, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai; Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad; Dr. Mridul K. Saggar, Executive Director (the officer of the Reserve Bank nominated by the Central Board under Section 45ZB (2) (c) of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934); Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra, Deputy Governor in charge of monetary policy – and was chaired by Shri Shaktikanta Das, Governor. Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Dr. Ashima Goyal and Prof. Jayanth R. Varma joined the meeting through video conference.

3. According to Section 45ZL of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, the Reserve Bank shall publish, on the fourteenth day after every meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee, the minutes of the proceedings of the meeting which shall include the following, namely:

-

the resolution adopted at the meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee;

-

the vote of each member of the Monetary Policy Committee, ascribed to such member, on the resolution adopted in the said meeting; and

-

the statement of each member of the Monetary Policy Committee under sub-section (11) of section 45ZI on the resolution adopted in the said meeting.

4. The MPC reviewed the surveys conducted by the Reserve Bank to gauge consumer confidence, households’ inflation expectations, corporate sector performance, credit conditions, the outlook for the industrial, services and infrastructure sectors, and the projections of professional forecasters. The MPC also reviewed in detail staff’s macroeconomic projections, and alternative scenarios around various risks to the outlook. Drawing on the above and after extensive discussions on the stance of monetary policy, the MPC adopted the resolution that is set out below.

Resolution

5. On the basis of an assessment of the current and evolving macroeconomic situation, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at its meeting today (October 9, 2020) decided to:

- keep the policy repo rate under the liquidity adjustment facility (LAF) unchanged at 4.0 per cent.

Consequently, the reverse repo rate under the LAF remains unchanged at 3.35 per cent and the marginal standing facility (MSF) rate and the Bank Rate at 4.25 per cent.

- The MPC also decided to continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward.

These decisions are in consonance with the objective of achieving the medium-term target for consumer price index (CPI) inflation of 4 per cent within a band of +/- 2 per cent, while supporting growth.

The main considerations underlying the decision are set out in the statement below.

Assessment

Global Economy

6. Incoming data point to a recovery in global economic activity in Q3 of 2020 in sequential terms, although downside risks have risen with the renewed surge in infections in many countries. Global trade is expected to be subdued. The rebound could turn out to be stronger among advanced economies (AEs) than in emerging market economies (EMEs). Global financial markets remain supported by highly accommodative monetary and liquidity conditions. Soft fuel prices and weak aggregate demand have kept inflation below target in AEs, although in some EMEs, supply disruptions have imparted upward price pressures.

Domestic Economy

7. On the domestic front, high frequency indicators suggest that economic activity is stabilising in Q2:2020-21 after the 23.9 per cent year-on-year (y-o-y) decline in real GDP in Q1 (April-June). Cushioned by government spending and rural demand, manufacturing – especially consumer non-durables – and some categories of services, such as passenger vehicles and railway freight, have gradually recovered in Q2. The outlook for agriculture is robust. With merchandise exports slowly catching up to pre-COVID levels and some moderation in the pace of contraction of imports, the trade deficit widened marginally sequentially in Q2.

8. Headline CPI inflation increased to 6.7 per cent during July-August 2020 as pressures accentuated across food, fuel and core constituents on account of supply disruptions, higher margins and taxes. One year ahead inflation expectations of households suggest some softening in inflation from three months ahead levels. Selling prices of firms remain muted, reflecting the weak demand conditions.

9. Domestic financial conditions have eased substantially, with systemic liquidity remaining in large surplus. Reserve money increased by 13.5 per cent on a year-on-year basis (as on October 2, 2020), driven by a surge in currency demand (21.5 per cent). Growth in money supply (M3), however, was contained at 12.2 per cent as on September 25, 2020. Banks’ non-food credit growth remains subdued. India’s foreign exchange reserves stood at US$ 545.6 billion on October 2, 2020.

Outlook

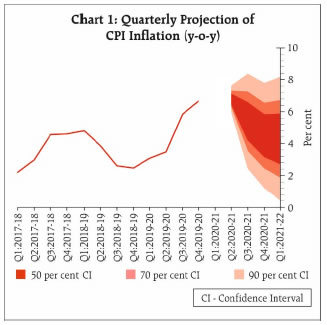

10. Turning to the outlook for inflation, kharif sowing portends well for food prices. Pressures on prices of key vegetables like tomatoes, onions and potatoes should also ebb by Q3 with kharif arrivals. On the other hand, prices of pulses and oilseeds are likely to remain firm due to elevated import duties. International crude oil prices have traded with a softening bias in September on a weak demand outlook, but domestic pump prices may remain elevated in the absence of any roll back of taxes. Pricing power of firms remains weak in the face of subdued demand. COVID-19-related supply disruptions, including labour shortages and high transportation costs, could continue to impose cost-push pressures, but these risks are getting mitigated by progressive easing of lockdowns and removal of restrictions on inter-state movements. Taking into consideration all these factors, CPI inflation is projected at 6.8 per cent for Q2:2020-21, at 5.4-4.5 per cent for H2:2020-21 and 4.3 per cent for Q1:2021-22, with risks broadly balanced (Chart 1).

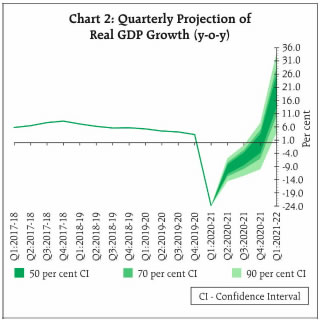

11. Turning to the growth outlook, the recovery in the rural economy is expected to strengthen further, while the turnaround in urban demand is likely to be lagged in view of social distancing norms and the elevated number of COVID-19 infections. While the contact-intensive services sector will take time to regain pre-COVID levels, manufacturing firms expect capacity utilisation to recover in Q3:2020-21 and activity to gain some traction from Q4 onwards. Both private investment and exports are likely to be subdued, especially as external demand is still anaemic. Taking into consideration the above factors and the uncertain COVID-19 trajectory, real GDP growth in 2020-21 is expected to be negative at (-)9.5 per cent, with risks tilted to the downside: (-)9.8 per cent in Q2:2020-21; (-)5.6 per cent in Q3; and 0.5 per cent in Q4. Real GDP growth for Q1:2021-22 is placed at 20.6 per cent (Chart 2).

12. The MPC is of the view that revival of the economy from an unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic assumes the highest priority in the conduct of monetary policy. While inflation has been above the tolerance band for several months, the MPC judges that the underlying factors are essentially supply shocks which should dissipate over the ensuing months as the economy unlocks, supply chains are restored, and activity normalises. Accordingly, they can be looked through at this juncture while setting the stance of monetary policy. Taking into account all these factors, the MPC decides to maintain status quo on the policy rate in this meeting and await the easing of inflationary pressures to use the space available for supporting growth further.

13. All members of the MPC – Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Dr. Ashima Goyal, Prof. Jayanth R. Varma, Dr. Mridul K. Saggar, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Shri Shaktikanta Das – unanimously voted for keeping the policy repo rate unchanged and continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. Dr. Shashanka Bhide, Dr. Ashima Goyal, Dr. Mridul K. Saggar, Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Shri Shaktikanta Das voted to continue with this accommodative stance at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year, with Prof. Jayanth R. Varma voting against this formulation.

14. The minutes of the MPC’s meeting will be published by October 23, 2020.

Voting on the Resolution to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 4.0 per cent

| Member |

Vote |

| Dr. Shashanka Bhide |

Yes |

| Dr. Ashima Goyal |

Yes |

| Prof. Jayanth R. Varma |

Yes |

| Dr. Mridul K. Saggar |

Yes |

| Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra |

Yes |

| Shri Shaktikanta Das |

Yes |

Statement by Dr. Shashanka Bhide

15. Two key goals from the monetary policy perspective at the present juncture, in which output growth has declined sharply and inflation pressures remain, are enabling sustained recovery of the economy and moderation in inflation rate.

16. The policy rates were left unchanged in the meeting of the MPC held on August 4-6, 2020 after a cumulative reduction of 115 basis points in rates between January and May 2020 in view of the prevailing modest GDP growth rate. The MPC policy statement of August 2020 reflected the concerns on the economic outlook as the COVID-19 pandemic began to take its toll.

17. The contraction in GDP in Q1: 2020-21, year-on-year basis, by 23.9 per cent, is a severe shock to the economy affecting employment and income. The decline in economic output is reflected in both production and expenditure accounts across most components. The Gross Value Added declined in all the non-farm sectors and in the case of demand, contraction in Private Final Consumption Expenditure and Gross Fixed Capital Formation was sharp. The only major component of demand that showed growth was Government Final Consumption Expenditure. Both exports and imports of goods and services declined, with imports declining more than the decline in exports. In the wake of COVID-19 pandemic, the extensive restrictions on the movement of goods and services barring the essential needs, imposed from the last week of March-May saw gradual relaxation from June onwards but a full economic recovery will require adjustments in the production and supply processes to control the spread of the disease. The recovery process will also be affected by the dynamic of the pandemic across the country as regional variations would also affect supply chains.

18. The present status of the impact of the pandemic suggests that there has been reduction in the daily new cases and mortalities due to COVID-19 towards the end of September but these numbers are large and the potential for an increase cannot be ignored. This would mean that relaxation of movement restrictions would help restore production, but the process would be gradual and subject to the measures that would be taken by the producers, providers of services and the consumers to control the spread of the virus.

19. Restoration of the supply side of the economy in a manner that is safe for the workers and the consumers is necessary for sustained economic recovery. There will be a need for changes in transportation and work places to mitigate the risks associated with the transmission of Covid 19.

20. The relative immunity of agriculture from the supply shocks may have been partly a result of the fact that the virus spread initially in urban areas and there were immediate efforts to limit the spread. The supply chains for the key food commodities were also exempted from transport restrictions, leading to sustenance of supply of these commodities.

21. There are indeed constraints that need to be addressed to restore the health of the firms that have lost revenues and returns. Access to credit to revive and expand production and markets is one of the essential factors in this regard. Bank lending rates to the productive sectors including housing have declined and a robust revival, however, would depend on the revival of demand. The weak demand conditions are also reflected in the decline in non-food bank credit upto September in 2020-21 over the previous year. Revival of consumer demand would require restoration of confidence in the safety in participation in normal economic activities and availability of health care. Public investment in improving infrastructure to achieve these goals would help build consumer confidence.

22. The current account balance, foreign capital flows and forex reserves position indicate relative stability in the external sector under a low demand equilibrium in both domestic and global markets. The depressed investment demand conditions are also reflected in the dampened state of demand for capital and weak growth in bank credit to non-food sector.

23. The fiscal position of the governments - both Centre and the States - is under pressure as the tax revenues have declined. The governments will be required to maintain their spending levels to meet the extraordinary demands to support livelihoods and lives in the present conditions.

24. Continued weakness in demand conditions would put greater stress on fiscal position and also the financial system.

25. The broad indicators of economic activity in the recent months suggest a revival from the sharp decline in Q1. Some of this improvement is on account of relaxation of movement restrictions, opportunities in sectors such as the pharma industry, and the requirement of critical inputs such as fertilisers. The more general pickup in activities is reflected in the expectation of improvement in capacity utilisation and perceptions of improved demand conditions in the recent surveys of enterprises reported by RBI.

26. The GDP will see sustained revival beginning from the second quarter of the year, with the rate of contraction from the levels of previous year declining steadily. As indicated in the MPC Resolution, the GDP growth is expected to be positive in Q4: 2020-21, although for the year as a whole, the growth rate is projected to be -9.5 per cent over the previous year. The Survey of Professional Forecasters conducted by RBI in September 2020 yields a median forecast of -9.1 per cent for the year 2020-21 and an assessment by NCAER’s Quarterly Review of the Economy places the GDP growth for 2020-21 at -12.6 per cent. Going forward into Q2 to Q4: 2020-21 these projections imply recovery in the economic activities from the large initial negative shock in Q1.

27. On the price front, the CPI inflation has stayed above 6.5%, Y-o-Y basis during July-August 2020. This is above the tolerance band of the inflation target set for the monetary policy. The food inflation averaged 8.4% during the same period and CPI based inflation rate for items excluding food and fuel was 5.6%. The food inflation will remain a concern as it is often driven by the perishable produce like vegetables, which cannot be controlled in the short term except by removing bottlenecks in the supply chain upto the retail level or additional fresh supplies. As noted in MPC Resolution, inflation is expected to moderate in Q3 and Q4: 2020-21. Two of the main drivers of price inflation on the supply side now are food and fuel. In the case of food, the favourable monsoon rains support the prospects of good harvest and its moderating impact on food inflation. The global conditions for crude petroleum prices appear stable from here onwards till the end of 2020-21.

28. There are clearly uncertainties facing the growth and inflation projections. There is also uncertainty over the speed with which the Covid-19 pandemic is brought under control, which also affects growth and inflation scenarios in the next 2-3 quarters. Towards the end of Q2, there are indications of revival of the economy after the relaxation of restrictions on transportation and businesses across the country. As supply chains adapt to the new conditions, recovery is expected to be stronger and sustained. To achieve this outcome, an accommodative monetary policy is needed at this juncture. Moderation in upward cost pressures on prices and decline in food inflation rates would require a quick output recovery from the supply side measures.

29. The outlook for growth and inflation for the next 3-4 quarters suggests the need for a policy environment enabling recovery of output. The inflationary pressures are a concern but present assessment reflects moderating inflationary pressures in the remaining quarters of the year.

30. Therefore, I vote for retaining the current policy rates and continuation of accommodative stance of monetary policy as long as necessary to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. I also vote to continue with this accommodative stance at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year.

Statement by Dr. Ashima Goyal

31. The MPC’s objectives are to meet its medium-run inflation target while supporting growth. Growth has fallen steeply while inflation is also above target. The question of what can revive growth as well as reduce inflation is best examined in the context of India’s macroeconomic structure.

32. COVID-19 led to crash in demand as well as disrupted domestic supply chains. As, under gradual unlocks, the latter revive while infections reduce, the supply-side is recovering. The heavy rains raised food prices but also promise a bountiful crop. Over the longer term, structural food surpluses, agricultural reforms and global changes in oil demand and supply can be expected to keep commodity prices soft. Reform is also reducing obstacles that raise production costs in India. Therefore, inflation can be expected to moderate. Research shows commodity price shocks and credible RBI guidance to be major determinants of inflation expectations.

33. India’s many youthful entrants to the labour force as well as migration to higher productivity jobs suggest it has an elastic supply curve but it is one that is subject to upward shocks1. Apart from supply-side features that raise costs, shocks include inflation expectations and changes in exchange rates. Moderating these shocks is the most effective way to reduce inflation in India.

34. Monetary-financial conditions have a relatively greater impact on aggregate demand and output growth while the composition of government expenditure and taxation affects costs. An elastic supply curve implies a demand squeeze has little impact on inflation but creates a large output loss. Moreover, excessive tightness hurts financial stability as much as excessive stimulus does. Necessary reforms over the last decade have improved the credit culture, governance, diversity and robustness in the financial system and conditions are ripe for a turnaround. COVID-19 creates an opportunity for a reversal of tight financial conditions2.

35. COVID-19 also creates uncertainty and precautionary hoarding of liquidity and savings. Therefore demand is now a greater constraint than supply. That inflation exceeds the MPC target when demand has crashed much below potential output suggests lockdown related shocks have pushed up the supply curve. This should reverse as lockdowns ease. That CPI inflation is much higher than WPI for the same items points to issues in retail supply. The CPI itself needs to be rebased to more accurately reflect the lower share of food in the consumption basket. Since the output gap is already so large, reducing demand and increasing the gap further cannot be the way to reduce inflation. Firms do tend to raise mark-ups to cover fixed costs when capacity utilization falls but reducing utilization further will only raise costs more.

36. Although in normal times India’s correctly estimated interest elasticity of demand is high, during crisis times it is difficult to induce more spending just through higher liquidity and lower interest rates. Fiscal deficits have risen countercyclically as tax revenues fell with the lockdowns. Even so, there is scope for further prudent expansion of government spending to boost demand and trigger private spending to raise growth. The expenditure should ideally be designed to relieve supply-side constraints. The ex-post fiscal deficit ratio falls as growth raises the denominator and rising tax revenues reduce the numerator.

37. Financing short-term rise in deficits requires keeping the cost of government borrowing low. Central banks worldwide are taking such actions. The monetary policy resolution committing to benign financial conditions for as long as it takes for revival will help both public and private borrowing and spending. Active and innovative steps, including counter-cyclical macro-prudential regulation, can improve incentives for appropriate action, allay fears, reduce risk aversion, make liquidity more widely available, improve transmission and bring down interest rate spreads.

38. Mitigating the impact of the unprecedented global health crisis has priority. It is important, however, there is neither over-reaction nor untimely reversal. Excess stimulus after the global financial crisis resulted in excess tightening in the decade that followed. Policy should aim for balance and use available space when it would be most effective. Forward-looking actions are aiming to be state-contingent, carefully calibrated to the evolving situation and to incoming data. Early measures required during the lockdown have been successfully reversed. For example, moratoria given have ended without major adverse impacts on borrowers or the financial system. Banks now do risk-based lending and the credit guarantee from the government allows private banks also to lend to MSMEs. Targeted restructuring and freer movement of liquidity through the economy will help firms survive, so that persistent damage is avoided and the economy recovers faster.

39. Inflation is at present above the target band although it is expected to come down. Therefore no change in the policy rate itself is appropriate while awaiting the impacts of on-going supply-side improvement, as well as for uncertainty around COVID-19 to dissipate. I therefore vote to keep the policy repo rate unchanged and also to continue with the accommodative stance as long as necessary – at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year – to revive growth, mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. The accommodative stance and the benign financial conditions it makes possible, together with the assurance it will not be reversed until the economy recovers, will support growth. The repo rate pause together with inflation guidance given will contribute to anchoring inflation expectations.

Statement by Prof. Jayanth R. Varma

40. I have agonized a great deal about dissenting (in part) with a resolution on a narrow technicality when I am in agreement with the spirit of the resolution: am I making a mountain out of a molehill and creating unnecessary confusion? After prolonged deliberation, I have come to the conclusion that a dissent may be painful, but it is more consistent with the obligation of MPC members to express their views independently and candidly. Even when a disagreement is more philosophical than operative, it should not always be relegated to the individual statement; I see some merit in occasionally elevating it to a dissent.

41. My preferred formulation of the forward guidance would have been as follows:

“The MPC also decided to continue with the accommodative stance as long as it is necessary to revive growth and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. The MPC expects to maintain a low policy rate and an accommodative stance during the current financial year and well into the next financial year.”

42. It differs from the actual MPC resolution in two respects. First, in my formulation, the date based forward guidance is not a decision but an expectation. In a world that is full of unpleasant surprises, the MPC must of necessity be data driven. Covid-19 was an example of a totally unanticipated growth shock that came out of nowhere. If a similarly unforeseeable inflation shock were to hit the economy, I find it hard to believe that the MPC will remain accommodative. In practice, I suspect that the word “decided” only means an intention to remain accommodative as long as realized outcomes do not diverge drastically from what is currently expected. I am firmly of the view that the MPC risks a damage to its credibility when it uses words that do not accurately reflect what it means. I therefore disagree with the choice of the word “decided” when it comes to the date based forward guidance in the MPC resolution.

43. Second, my formulation is for a somewhat longer period and explicitly refers to interest rates. In my view, the principal motivation for the forward guidance is the fact that India has one of the steepest yield curves in the world. The Indian yield curve is extremely steep beyond a maturity of about a year: in the short term segment (1-2 years), the intermediate term segment (2-5 years) and the long term segment (5-10 years). However, in the money market segment (up to a maturity of nearly one year), the yield curve is close to the reverse repo rate of 3.35% (which is the effective policy rate today because of the liquidity support). To have the desired impact, it is desirable that the forward guidance extend beyond the one year horizon at which the steepness of the yield curve sets in. Forward guidance of six months in the MPC resolution is in my view suboptimal. I would also point out that the weakness of investments in the Indian economy predates the Covid-19 pandemic, and this merits a longer term response that goes beyond six months.

44. One of the hallmarks of a credible inflation targeting regime is a substantial compression of the inflation risk premium. If the market expects inflation to average close to the target rate of inflation, then, by definition, inflation risk is low and consequently the inflation risk premium should also be very small. What remains is essentially the liquidity risk premium which cannot explain the extraordinary steepness of the Indian yield curve.

45. It appears to me that the steep yield curve reflects a lack of credibility of the MPC’s existing accommodative guidance. The introduction of dated guidance in the MPC resolution is an attempt to solve this problem, and my only difficulty with this solution is the word “decided”. Just as the brakes allow the car to travel faster, the MPC’s guidance will be more effective if it works alongside and not in conflict with its inflation fighting resolve. I prefer the word “expected” because it would preserve the commitment of the MPC to respond aggressively to inflation shocks that lie well above the upper band of the fan chart (Chart 1 of the Monetary Policy Statement).

46. I believe that excessively high long term rates are inflicting damage to the economy in two ways. First, a significant part of the easing of policy rates is not being transmitted to longer term rates that form the benchmark for corporate borrowing and investment decisions. Excessive long term rates exacerbate the collapse of investments in the economy. Second, high long term rates cause an appreciation of the real effective exchange rate by stimulating foreign capital inflows into our bond markets at a time when the collapse of investment has caused the current account to swing into surplus.

47. A sharp reduction in long term rates is therefore important. On the other hand, with short term rates already at 3.35%, the incremental benefits of a furthering lowering of this rate in the current macroeconomic environment are relatively low and not commensurate with the risks. So I support maintaining the policy rate at its current level. I also support the accommodative stance and liquidity support that drive short term rates towards the reverse repo rate rather than the repo rate.

Statement by Dr. Mridul K. Saggar

48. At the time of the August MPC, while noting that monetary policy was being framed under large data and forecast uncertainties, I had also indicated that growth could fall more and, inflation less, than the consensus estimates that prevailed at that point. Market consensus has since moved significantly. Survey of Professional Forecasters now predicts 2020-21 growth at (-)9.1 per cent, down from (-)5.8 per cent in August and headline inflation to fall to 4.2 per cent in Q4:2020-21, up from 3.0 per cent. The baseline projections in the MPC resolution place growth at (-)9.5 per cent and headline inflation at 5.4-4.5 per cent in H2:2020-21 and 4.3 per cent for Q1:2021-22. The latest projections reaffirm that inflation will fall in line with the target, while growth has plummeted, thus decidedly shifting the growth-inflation policy trade-off in favour of supporting growth within the flexible inflation targeting paradigm.

49. During Q1:2020-21, the economy faced its deepest contraction ever, which was also the worst amongst G20 countries. Despite marked sequential improvements in high frequency indicators of real activity, many of them are yet to normalise to their pre-pandemic levels that were already sub-par as the economy had slowed to a 11-year low in 2019-20. The GDP is likely to contract close to double-digit mark in Q2:2020-21. A range of model-based exercises, as well as my judgment superimposed on these, suggest that output gap in terms of levels of GDP will close only towards the end of 2021-22, even though a technical rebound is likely to push the economy to above average growth in that year on a low base. Investment, that typically comprise about a third of real aggregate demand, contracted 47 per cent in Q1:2020-21. With seasonally adjusted capacity utilisation for surveyed manufacturing firms dropping to 48 per cent in Q1:2020-21, the large slack already visible in 2019-20 has deepened further. As such, investment may take time to recover. Moving ahead, there is tough row to hoe requiring acorns to be fed in the form of complementary actions to support recovery to trend growth in the coming years.

50. Though inflation is currently above the upper tolerance band, it is not monetary in nature. Supply disruption in food, increase in taxes on fuel and liquor, and surge in gold prices catalysed by risk-off has lifted inflation. Ex-food, ‘fuel and light’, gold and ‘pan, tobacco and intoxicants’, inflation stands at 4.4 per cent, i.e. 2.3 percentage points lower than the headline inflation. In my view, headline inflation should start softening from October. Apart from favourable base effects, the unlocking has picked speed and would significantly reduce supply chain bottlenecks causing both agriculture and non-agricultural prices to correct. Monsoon risks to inflation have dissipated. Cumulative rainfall has been 9 per cent above long period average with its temporal and spatial distribution satisfactory. Area sown under Kharif has expanded by 4.8 per cent. Reservoir levels are 15 per cent above last 10-year average, lifting up Rabi prospects. The First Advance Estimates of Kharif point to substantial increase in output of crops like pulses, oilseeds and sugarcane that can have a salutary effect on food and processed food prices and leave enough margin of error for possible subsequent downward revisions in data. With marked increase in area sown under foodgrains, alongside the buffer of food stock at double the norms, prices should soften. Vegetable prices that have exhibited persistence at elevated levels due to weather-related disturbances should also correct starting December. With resumption of businesses by small poultry, high prices in protein items should witness some correction. As yet, there are no signs of generalisation of relative price shock from food items and agriculture and rural wage inflation has stayed muted.

51. The current high retail margins have prevailed as consumers avoid scouting for cheaper prices amidst social distancing. The phenomenon of such less competitive markets have been observed in past pandemics as well, such as the one that contributed to the Eisenhower recession in the United States. However, the unlock intensity now matches the lockdown stringency and with new confirmed Covid-19 cases starting to decline in recent weeks, unless there is strong second wave, supply chains should get near normalised as early as end of the current calendar year, setting off price corrections. However, demand will take time to normalise and weakness may persist into the next year. In these circumstances, corporate pricing power is unlikely to recover, though upside risks to inflation remain from possible collusive behaviour in less competitive industries, as also further unforeseen supply disruptions in food. As a baseline, headline should converge to core inflation, with both softening.

52. Three macro-financial risks currently concern me that have implications for monetary policy. First, if growth contractions stay for long, the hysteresis or scarring that has been substantially arrested by nimble-footed policy actions could stage a comeback creating renewed feedback loops within public, corporate and bank balance sheets that would impact the stock of debt as well as fiscal and saving-investment balances. If this happens, recovering potential output, some of which may be lost to hysteresis, will take longer. It will also push the neutral interest rate lower than before. Despite front-loaded action, monetary policy should, therefore, stay accommodative. The fiscal restraint observed so far provides some room for it. However, with term spreads already widening above historical levels in 2019-20 and in H1:2020-21 on back of widening fiscal gap that has necessitated larger government borrowing programmes, the unpleasant arithmetic is evident in supplies of papers more than doubling in two years. Consequently, the yield curve slope is hardly a predictor of growth or expected inflation. This is not unique to India and term spreads have been higher and have widened much more during current pandemic in many other emerging markets due to pro-cyclical nature of fiscal policies that leave little counter-cyclical space. As typically fiscal authorities have a first mover advantage in the game of chickens, monetary policy will naturally have to factor this in its stance to avert Nash equilibria as a pure strategy. In this milieu, monetary and liquidity easing in India has effectively kept government market borrowing costs at a 16-year low with attendant benefits for funding costs that are obvious but hard to quantify precisely in absence of counterfactual.

53. Second, if current real negative interest rates fall further, it may generate significant distortions that could adversely affect aggregate savings, current account and medium-term growth in the economy. With retail fixed deposit rates currently ranging between 4.90-5.50 per cent for tenors of 1-year or more and the headline inflation prevailing above that for some months now, there has been a negative carry for savers. While expected future inflation is lower and leaves some policy room, it is prudent to hold policy rates for now.

54. Third concern relates to interactions between monetary policy and financial stability, which could intensify further, especially later into next year. Though low for long interest rates risk build-up of corporate and household leverage, unprecedented contraction entails policy-trade-offs imparting primacy to rebuilding consumer and business confidence over the next 2-3 quarters by taking some policy uncertainty out of their decisions. In this milieu, forward guidance can play an important role.

55. Considering all the above, I vote for leaving the policy rate unchanged. Further considering that output gap may close only towards the end of 2021-22 and that, going forward, the demand destruction caused by the pandemic, coupled with improvements in logistic networks of production and distribution, may exert significant downward pressure on headline and core inflation, I vote for the accommodative stance and the forward guidance provided in the resolution.

Statement by Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra

56. The projections of real GDP growth for 2020-21 that are set out for the first time in the MPC’s resolution provide a sense of the wounds on the soul of the economy inflicted by COVID-19. If the NSO’s provisional estimates for Q2 that are expected at the end of November corroborate at least the direction of these forecasts, India has entered a technical recession in the first half of the year for the first time in its history. GDP is an aggregative indicator of economic activity and hides the extent of human misery and the loss of social and human capital caused by the health crisis. Nonetheless, if the projections hold, the level of GDP would have fallen approximately 6 per cent below its pre-COVID level by the end of 2020-21 and it may take years to regain this lost output. There is also an anecdotal sense that the economy’s potential output has fallen, and the post-COVID growth trajectory will look very different from what has been recorded so far. Changes in social behaviour and norms of commercial and workplace engagements may accentuate this structural change.

57. Progressive unlocking of the economy has brought people out of isolation and some high frequency indicators into the green. While this has raised optimism about the much-awaited recovery, perhaps, pragmatic caution is warranted. The COVID curve is arching inwards, from the cities where infections had hitherto festered, into interior regions. The fear of a second wave looms over India; already it has forced lockdowns across Europe, Israel and Indonesia, and India, with the second highest caseload of infections and over-stretched healthcare infrastructure, cannot be immune. In the absence of intrinsic drivers, the recovery may last only until pent-up demand has been satiated and replenishment of inventories has been completed. Empirical evidence suggests that consumption-led recoveries are shallow and short-lived. Exports could be a driver, but with the WTO’s latest projection of a decline in world trade volume by 9.2 per cent in 2020, the role of exports in powering a durable revival is likely to be circumscribed. This underscores the critical role of investment in engineering the turnaround in the economy and sustaining it over the medium-term. Depressed capacity utilisation in manufacturing, inventory overhang in residential housing, impaired balance sheets of corporates and financial institutions, and pervasive business pessimism are combining to create formidable drags on investment sentiment. Consequently, an investment-less recovery is doomed to be ephemeral. Policy intervention accordingly assumes a vital role. Illustratively, public investment can play both a gap-fill and crowding-in role. Monetary policy can engender favourable financing conditions by lowering the cost of capital and by narrowing risk spreads on financial instruments.

58. In the current milieu, however, both monetary policy and fiscal policy in India face tightening constraints, some idiosyncratic. For fiscal policy, it is the collapse of tax revenue – by 32 per cent in the first quarter; consequently, the centre’s revenue deficit during April-August is 121.9 per cent of budget estimates. For monetary policy, it is the persistence of headline inflation above 6 per cent for the third month in succession. Structural reforms to unlock growth impulses are needed, but may lack social traction in an atmosphere of depressed growth and employment, and high uncertainty.

59. In the context of headline inflation ruling above the upper tolerance limit of the target since June 2020, the role of monetary policy has come under scrutiny. It has been argued that while inflationary pressures may emerge from supply bottlenecks and cost pushes, inflation cannot become generalised and persistent unless it becomes a monetary phenomenon, i.e., it is accommodated by an increase in aggregate demand as reflected in an expansion of money supply or by a decrease in policy interest rates. Monetary policy has adopted an ultra-accommodative stance to revive growth and mitigate the effects of COVID-19. Liquidity operations in support of this stance have infused sizable liquidity into the system, reflected in reserve money expansion of 17.6 per cent adjusted for the first-round effects of cash reserve ratio changes. This has, however, not translated into a commensurate increase in money supply because of a money multiplier depressed by a sharp increase in the currency-deposit ratio, and remunerated reserves parked in reverse repo with the RBI over and above CRR requirements. Consequently, the rate of money supply is averaging 12 per cent in nominal terms and only 6 per cent in real terms. In terms of quarterly seasonally adjusted annualised rates, a negative money gap has opened up recently.

60. In a quarterly vector auto regression (VAR) framework, money supply and policy rate reductions together contribute only 4 per cent of the deviation of inflation from its target. The contribution of supply shocks from food and fuel prices account for 71 per cent of inflation deviations in the first half of 2020-21, followed by 28 per cent from unanchored inflation expectations (deviations of trend inflation from target). Changes in exchange rates and asset prices together contribute a little less than 12 per cent. Inflation is pulled down by 15 per cent by the negative demand shock from COVID-19.

61. Under these conditions, it is essential for monetary policy to remain accommodative and opportunistically exploit the headroom that opens up when inflation recedes, as it is projected in the second half of 2020-21. Three aspects need to be emphasised. First, it is important to separate false starts from durable growth drivers. In this context, all efforts need to be trained on the revival of investment. Second, in the evolving situation in which monetary policy is committed to an accommodative stance, it is necessary to monitor inflation dynamics closely for signs of generalization and persistence. For this purpose, all indicators of aggregate demand, including monetary and credit aggregates, warrant continuous examination for inflation impulses. Third, with unprecedented contractions in economic activity and elevated inflation posing a razor’s edge trade-off fraught with uncertainty, forward guidance has to be clear and decisive. The stance of policy conveys forward guidance on the future trajectory of short-term interest rates, which is well within the MPC’s remit. On this, therefore, communication has to be unambiguous and, given the evolving situation, specific in order to anchor expectations.

62. I vote to keep the policy rate unchanged and for retaining the accommodative stance of policy as set out in the MPC’s resolution.

Statement by Shri Shaktikanta Das

63. After the sharpest contraction in economic activity in Q1:2020-21, a number of high frequency indicators of economic activity for Q2:2020-21 indicate a sequential improvement. The recovery in all likelihood would be led by rural demand. In urban areas too, there are indications of an uptick in consumption demand with passenger vehicles emerging out of contraction in August, rebound in GST e-way bills to pre-pandemic levels, sequential improvement in GST revenues in September and a steady improvement in PMI manufacturing and services.

64. Accordingly, the recovery is expected to be multi-speed depending on sectoral realities. Forward looking surveys conducted by the Reserve Bank are also indicating a sequential firming up of the recovery. Households expect an improvement in general economic situation, employment and income over a one year ahead horizon. Capacity utilisation saw some improvement in Q2:2020-21 and a further pick-up is expected from Q3 onwards. Manufacturers expect expansion in production volumes and new orders to continue through Q1:2021-22. Business Expectation Index (BEI) also suggests a move to expansion zone in Q3:2020-21.

65. There are, however, downside uncertainties that could put sand in the wheels of this nascent recovery. Primary among them is the risk of a second wave of COVID-19. Private investment activity is likely to be subdued, even as domestic financial conditions have eased significantly. External demand is expected to remain anaemic with sharp contraction in global economic activity and trade. Overall, we expect a likely reduction in the rate of contraction in GDP during Q2:2020-21 and a return to positive growth by Q4:2020-21. Despite sequential improvement in Q3 and Q4, the full year GDP is expected to contract by 9.5 per cent with a strong rebound next year.

66. Inflation remained above the upper tolerance threshold of 6 per cent since June, with signs of aggravation of price pressures. The surge in inflation in India in recent period is in stark contrast with the experience of other major emerging market economies (EMEs) where inflation moderated relative to pre-lockdown period. Adverse supply side factors along with increase in retail margins continue to impinge on food and non-food components of CPI. Food (with a weight of around 46 per cent in overall CPI) contributed disproportionately at around 60 per cent to the surge in inflation. In addition, costs of doing business have gone up due to additional sanitisation related expenditures, social distancing norms and labour shortfalls.

67. On the outlook for inflation, food inflation should moderate going forward on a combination of good kharif harvest and a favourable rabi season. Households polled by the Reserve Bank expect 3-month ahead inflation expectations to somewhat soften. As economic activity further normalises and supplies are restored, cost push price pressures faced by firms are likely to dissipate. However, should supply side shocks, especially to food persist, they can destabilise inflation expectations. Overall, in our assessment, headline inflation would moderate in H2 of the current year and further in Q1 of next fiscal year.

68. The Reserve Bank’s proactive management of liquidity through both conventional and unconventional measures, amounting to ₹12.3 lakh crore or 6.1 per cent of nominal GDP of 2019-20, has helped to keep systemic liquidity in abundance and easy financial conditions reflected in the narrowing of term and risk premia in various market segments. During March-August 2020, monetary transmission improved significantly reflecting the combined impact of surplus liquidity and enhanced coverage of the external benchmark-based pricing of loans. However, despite continued guidance of accommodative stance as long as necessary and ample surplus liquidity, the financial markets remained somewhat nervous and at variance with our expectations. The market participants were also concerned about the stance going forward.

69. Monetary policy works through financial markets which serve as the conduit of transmitting policy signals to the real economy. For seamless propagation of policy impulses, it is necessary that the monetary authority’s policy intent is clearly understood by market participants so that there are no expectational mismatches between the two. Accordingly, MPC should strengthen its forward guidance by indicating that the accommodative stance would continue as long as necessary - at least during the current financial year and into the next financial year - to revive growth on a durable basis and mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the economy, while ensuring that inflation remains within the target going forward. This enhanced guidance should strengthen and quicken the pace of transmission to longer-term yields and help support consumption and investment demand in the economy. Higher investment in conjunction with recent structural reforms measures by the government would help improve supplies and alleviate supply bottlenecks and also contribute to softening of inflation.

70. Monetary policy at this stage has to provide adequate support to ensure a robust revival of the economy from the devastating effects of COVID-19, while at the same time ensuring that any persistence of elevated inflation does not lead to unanchoring of inflation expectations. With the supply side disruptions that are seen to drive the current inflationary pressures likely to be transient and wane out in months ahead as economy normalises, there is merit in looking through the current high levels of inflation and persevere with the accommodative stance for monetary policy as long as necessary to revive growth on a durable basis. Moreover, taking into account the projected moderation in inflation and the large output loss, I vote to keep the policy rate unchanged at present and continue with the accommodative stance, during the current financial year and into the next financial year, at the least. This would help to reduce uncertainty and market volatility. This would also enhance confidence in the monetary policy resolve to support the growth recovery process while ensuring that inflation remains within the target. I recognise that there exists space for future rate cuts if the inflation evolves in line with our expectations. This space needs to be used judiciously to support recovery in growth. Meanwhile the ongoing transmission of past monetary policy actions would help ease financial conditions further.

(Yogesh Dayal)

Chief General Manager

Press Release: 2020-2021/533

|