4.1 Credit markets have, historically, played a crucial role in sustaining growth in almost all countries, including advanced countries, which now have fully developed capital markets. Credit markets perform the critical function of intermediation of funds between savers and investors and improve the allocative efficiency of resources. Banks, which are major players in the credit market, play an important role in providing various financial services and products, including hedging of risks. Credit markets also play a key role in the monetary transmission mechanism.

4.2 Extension of credit, however, also poses some risks, which range from pure credit risk to the risk of over-lending. While pure credit risk is the risk of loss due to non-payment by the borrower, even though adequate precautions are taken at the time of loan origination, the risk of over-lending arises when banks extend loans without appropriate credit appraisal and due diligence on account of excessive optimism about future prospects. While pure credit risk may not be widespread and may normally not create systemic problems, over-lending is unsustainable and potentially destabilising for the system. Regulators in all countries, therefore, while seeking to maintain adequate growth, guard against its adverse impact by instituting appropriate regulatory and supervisory policies and strengthening of prudential norms.

4.3 The credit market in India has traditionally played a predominant role in meeting the financing needs of various segments of the economy. Credit institutions range from well developed and large sized commercial banks to development finance institutions (DFIs) to localised tiny co-operatives. They provide a variety of credit facilities such as short-term working loans to corporates, medium and long-term loans for financing large infrastructure projects and retail loans for various purposes. Unlike other segments of the financial market, the credit market is well spread throughout the country and it touches the lives of all segments of the population.

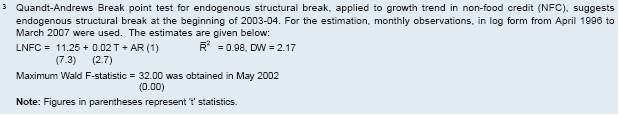

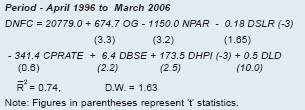

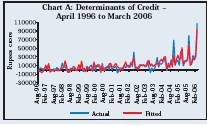

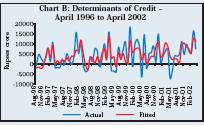

4.4 Prior to initiation of financial sector reforms in the early 1990s, the credit market in India was tightly regulated. Bank credit was the principal focus of monetary policy under the credit planning approach adopted in 1967-68. In the absence of a formal intermediate target, bank credit – aggregate as well as sectoral – came to serve as a proximate target of monetary policy. Monetary policy up to the mid-1980s was predominantly conducted through direct instruments with credit budgets for banks being framed in sync with monetary budgeting (Mohan, 2006a). The credit market was characterised by credit controls and directed lending. Various credit controls existed in the form of sectoral limits on lending, limits on borrowings by individuals, stipulation of margin requirements, need for prior approval from the Reserve Bank, if borrowing exceeded a specified limit (under the Credit Authorisation Scheme), and selective credit controls in the case of sensitive commodities. Lending interest rates by all types of credit institutions were administered. Credit markets were also strictly segmented. While commercial banks catered largely to the short-term working capital requirements of industry, development finance institutions focused mainly on long-term finance. Competition in the credit market was also limited. This led to several inefficiencies in the credit market.

4.5 A wide range of regulator y reforms, therefore, were introduced as part of financial sector reforms in the early 1990s to improve the efficiency of the credit market. As a result, the credit market in India has undergone structural transformation. The credit market has become highly competitive even though the number of credit institutions has reduced due to merger/conversion of two DFIs into banks, weeding out of unsound NBFCs and restructuring of urban co-operative banks and RRBs. Credit institutions now offer a wide range of products. They are also free to price them depending on their risk perception.

4.6 In the above backdrop, this chapter analyses trends in the credit market in India, with a special focus on various aspects of rapid credit growth in recent years. The chapter is pided into six sections. Section I briefly explains the significance of the credit market in economic growth. The structure of the credit market in India is delineated in Section II. Policy developments relating to the credit market since the early 1990s have been set out in Section III. Trends in credit growth in India in the post-reform period are analysed in Section IV. Recent trends in bank credit growth and their implications are also

REPORT ON CURRENCY AND FINANCE

analysed in this section. Section V suggests some measures with a view to further strengthening the role of the credit market in India. Concluding observations are presented in Section VI.

I. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE CREDIT MARKET

4.7 There is a broad consensus, among both academics and policy makers, that a developed financial system spurs economic growth through a number of channels: (i) acquisition of information on firms; (ii) intensity with which creditors exert corporate control; (iii) provision of risk-reducing arrangements; (iv) pooling of capital; and (v) ease of making transactions (Levine, 2004). There are two mechanisms for mobilising savings and channeling them into investments, viz., bank-based and market-based, as alluded to in Chapter I. Empirical evidence reveals that while a more developed financial sector is associated with higher income levels, there is no clear pattern with regard to financial structure.

4.8 In most countries, both the systems exist even as one system may be more dominant than the other. However, of the two systems, credit institutions have the distinct advantage in information gathering and processing to monitor the efficiency and productivity of projects. In fact, in recent years the existence of banks, which are the major players in the credit market, is attributed more to their information gathering capacity arising out of the existence of asymmetric information and moral hazard problems, than to the classic explanation relating to their ability to mobilise savings and channeling them into investment. Savers usually have incomplete information on the affairs of companies, which makes it more difficult for companies to obtain direct financing from the market. Intermediation by banks mitigates such agency problems. When the cost of acquiring information on a company by the providers of financial resources is high, the process of financing companies can be done more efficiently if the prospective investors are able to delegate the collection of such information to a specialised organisation (Diamond, 1984). Thus, financial intermediation is justified on the grounds of information gathering and company-monitoring functions performed by banks. By reducing the costs of acquiring and processing information, financial institutions encourage mobilisation of savings and improve resource allocation. Banks can also persify risk among a number of companies.

4.9 Firms in developing countries generally tend to rely more on debt finance, including bank credit. The emphasis on credit rather than equity arises due to various reasons. The cost of equity in developing economies is often much higher than the cost of debt due to the existence of higher perceived risk premia than in developed countries. The existence of artificially repressed interest rates contributes further to the problem. The other reasons for the heavy reliance on debt in developing countries include the fragility of their equity markets, lack of suitable accounting practices and the absence of adequate corporate governance practices. Given the high dependence on bank credit and lack of substitutes for external finance, firms in developing economies are generally highly sensitive to changes in the cost and flow of credit.

4.10 Credit markets in developing countries, in particular, play an important role, where apart from industry, agriculture is also an important segment of the economy. Besides, there are also a large number of small and medium enterprises in the industrial and service sectors, which are not able to access the capital market and have to depend on the credit market for their funding requirements. Thus, the importance of banks and other lending institutions in developing countries can hardly be overemphasised.

4.11 Commercial banks, given their preeminent position in the regulated financial sector, dominate the credit market. The quantity of loans created by the banking system is generally a function of both the willingness and ability of banks to lend. In an economy with ceilings on lending rates, banks face a higher credit demand than they can effectively supply, thus, necessitating reliance on a credit rationing mechanism. In a non-repressed financial system, on the other hand, the borrowers are, in principle, differentiated along the lines of risk characteristics and riskier borrowers are charged higher interest rates to account for default probabilities. This, however, may create the problem of adverse selection. Though riskier projects bring higher returns, banks, out of sustainability consideration, need to optimise the risk of their portfolio.

4.12 Another important factor influencing the supply of credit is the amount of reserves available from the central bank to the banking system. A large pre-emption of central bank money by the Government may constrain reserve supply to the banking system, thus, affecting their capacity for credit creation. Moreover, credit expansion could also be an endogenous process, i.e., it is the demand for credit that may drive the banking system’s ability to create credit in the economy.

4.13 Development of the credit market plays an important role in the monetary transmission mechanism. The traditional interest rate channel, represented by the ‘money view’, mainly focuses on the liability side as banks create money through chequable deposits. The asset side is not emphasised as firms’ financial structure is believed to be neutral to borrowings through loans from banks or through issuance of securities. This is based on the assumption that different financial assets such as bonds and bank loans are perfect substitutes. However, in terms of ‘credit view’, bonds and bank loans are not seen as perfect substitudes primarily because of information asymmetries. Firms facing informational problems find it more expensive to borrow through bonds than availing loans from banks.

4.14 According to the ‘credit view’, the direct effect of monetary policy is amplified by changes in the external finance premium (EFP) in the same direction. An EFP is the difference in cost of funds raised externally (by way of issuing equity or debt) and funds generated internally (retained earnings). Thus, monetary tightening increases EFP, while easing of monetary policy reduces EFP. As a result, the impact of a given change in short-term policy interest rates on demand and output is magnified, which reinforces the effects of variation in interest rates (Bernanke and Gertler, 1995). In this context, the most representative theoretical model of the credit view is that of Bernanke and Blinder (1988). It is a modification of the IS/LM framework and contains all the elements that allow for the theoretical definition of imperfect substitution between credit on the one hand, and bonds and securities on the other (Box IV.1). As a policy guide, Bernanke and Blinder conclude that if money demand shocks are more important than credit demand shocks, then a policy of targeting credit is probably better than a policy of targeting money.

4.15 Given that a developed financial intermediation system facilitates growth, policy makers tend to liberalise the system to facilitate financial development. The literature, however, suggests that authorities should take adequate caution in adopting a liberalised policy frameworks intended to develop the financial sector (IMF, 2006). Lax supervision and rudimentary regulation of newly liberalised financial institutions, often combined with a volatile macroeconomic environment, have led to systemic crises (Lindgren, et al, 1996 and Caprio and Klingebiel, 2003). Similarly, there is econometric evidence that shows that banking crises are more likely to occur in countries associated with liberalised credit markets operating in weak institutional environments. The East Asian crisis underlined the risks to economic stability and growth that a weak or vulnerable financial sector could pose.

II. INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE CREDIT MARKET IN INDIA

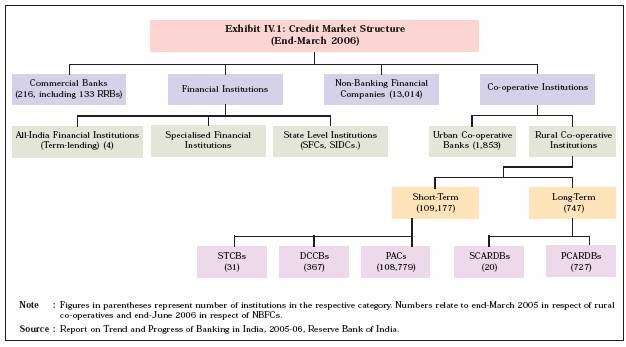

4.16 The credit market structure in India has evolved over the years. A wide range of financial institutions exist in the country to provide credit to various sectors of the economy. These include commercial banks, regional rural banks (RRBs), cooperatives [comprising urban cooperative banks (UCBs), State co-operative banks (STCBs), district central co-operative banks (DCCBs), primary agricultural credit societies (PACS), state co-operative and agricultural rural development banks (SCARDBs) and primary co-operative and agricultural rural development banks (PCARDBs)], financial institutions (FI) (term-lending institutions, both at the Centre and State level, and refinance institutions) and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) (Exhibit IV.1).

4.17 Scheduled commercial banks constitute the predominant segment of the credit market in India. In all, 83 scheduled commercial banks were in operation at end-March 2006. The commercial banking sector is undergoing a phase of consolidation. There have been 12 mergers/amalgamations since 1999. The RRBs, which were set up in the 1970s to provide agricultural and rural credit, are being restructured at the initiative of the Government of India. Till October 31, 2006, 137 RRBs were amalgamated to form 43 new RRBs, bringing down the total number of RRBs in the country to 102 from 196 at end-March 2005.

4.18 The co-operative banking system, with two broad segments of urban and rural co-operatives, forms an integral part of the Indian financial system. Urban cooperative banks, also referred to as primary cooperative banks, play an important role in meeting the growing credit needs of urban and semi-urban areas of the country. The UCBs, which grew rapidly in the early 1990s, showed certain weaknesses arising out of lack of sound corporate governance, unethical lending, comparatively high levels of non-performing loans and their inability to operate in a liberalised environment. Accordingly, some of the weak UCBs have been either liquidated or merged with other banks. As a result, the number of UCBs declined from 1,942 at end-March 2001 to 1,853 by end-March 2006.

4.19 Historically, rural co-operative credit institutions have played an important role in providing institutional credit to the agricultural and rural sectors. These credit institutions, based on the nature of their lending operations, have typically been pided into two distinct segments, commonly known as the short-term cooperative credit structure (STCCS) and the long-term co-operative credit structure (LTCCS). The STCCS, comprising PACS at the village level, DCCBs at the intermediate level, and the STCBs at the apex level, provide crop and other working capital loans to farmers and rural artisans primarily for short-term purposes. The LTCCS, comprising SCARDBs at the State level and PCARDBs at the district or block level, provide typically medium and long-term loans for making investments in agriculture, rural industries and, in the recent period, housing. However, the structure of rural co-operative banks is not uniform across all the States of the country. Some States have a unitary structure with the State level banks operating through their own branches, while others have a mixed structure incorporating both unitary and federal systems.

4.20 Financial institutions owed their origin to the objective of state driven planned economic development, when the capital markets were relatively underdeveloped and judged to be incapable of meeting adequately the long-term requirements of the economy. Over the years, a wide range of FIs, mostly Government owned, came into existence to cater to the medium to long-term financing requirements of different sectors of the economy. FIs played a key role in extending development finance in India and for this purpose they were given access to concessional finance in the form of Government guaranteed bonds and Long-Term Operations (LTO) Fund of the Reserve Bank. However, the government’s fiscal imperatives and market dynamics forced a reappraisal of the policies and strategy with regard to the role of FIs in the economy and the concessional finance was phased out by the mid-1990s. A major restructuring in the financial sector occurred when two major FIs, viz., ICICI and IDBI converted into banks. Thus, this particular segment of the credit market has shrunk significantly in recent years.

4.21 NBFCs encompass a heterogeneous group of intermediaries and provide a whole range of financial services. Though heterogeneous, NBFCs can be broadly classified into three categories, viz., asset finance companies (such as equipment leasing and hire purchase), loan companies and investment companies. A separate category of NBFCs, called the residuary non-banking companies (RNBCs), also exists as it has not been categorised into any one of the above referred three categories. Besides, there are miscellaneous non-banking companies (Chit Fund), mutual benefit financial companies (Nidhis and unnotified Nidhis) and housing finance companies. The number of NBFCs operating in the country was 51,929 in 1996. Following the amendments to the provisions contained in Chapter III-B and Chapter III-C of the Reserve Bank of India Act, NBFCs both, deposit taking and non-deposit taking, are required to compulsorily register with the Reserve Bank. One of the conditions for registration for NBFCs was a minimum net owned fund (NOF) of Rs.25 lakh at the entry point. This limit was subsequently enhanced to Rs.2 crore for new NBFCs seeking grant of Certificate of Registration on or after April 21, 1999. The Reserve Bank received 38,244 applications for grant of certificate of registration (CoR) as NBFCs till end-March 2006. Of these, the Reserve Bank approved 13,141 applications, including 423 applications of companies authorised to accept/hold public deposits. Due to consolidation in the sector, the number of NBFCs declined to 13,014 by end-June 2006.

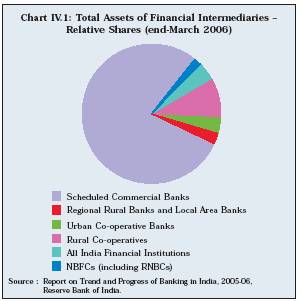

4.22 Of all institutions, in terms of assets, commercial banks constitute the largest category, followed by rural co-operatives (Chart IV.1).

Box IV.1

The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy

The impact of monetary policy on the real economy operates through various channels. Under the conventional approach, referred to as the ‘money view’, monetary policy influences the economy via the interest rate. The alternate channel, that emphasises credit conditions as the route of monetary transmission, is of relatively recent origin and is referred to as the ‘credit view’. Genesis of the credit view could be traced to the celebrated work of Bernanke and Blinder (1988), which presented the IS-LM framework augmented with bank-intermediated loans. It argued that since loans and bonds are not perfect substitutes, monetary policy operates not only through the conventional money channel but also through the credit channel. According to the ‘credit view’, a change in monetary policy that raises or lowers open market interest rates tends to change the external finance premium in the same direction. External finance premium is the difference between the cost of funds raised externally and the funds raised internally. Because of this additional effect of policy on the external finance premium, the impact of monetary policy on the cost of borrowing and consequently on real spending and real activity is magnified (Bernanke and Gertler, 1995). There are three reasons for which the credit channel is important. First, evidence suggests that credit market imperfections of the type crucial to the credit channel do indeed affect firms’ employment and spending decisions. Second, evidence suggests that small firms, which are more likely to be credit constrained, are hurt more by tight monetary policy than their larger counterparts. Third, asymmetric information - the core of credit channel analysis - proves to be highly useful in explaining some other important phenomena: e.g., why do financial intermediaries exist; structure of the financial sector; and why do financial crises occur (Mishkin, 1996).

There are two channels through which credit conditions are expected to affect monetary transmission. First, the ‘bank lending’ channel, that operates through modulation of bank reserves, is affected by monetary policy. Contractionary/ expansionary policy limits or enhances the ability of banks to lend and thereby reduces/increases investment and output. The second, the ‘balance sheet’ channel works through net worth of the borrowers. Contractionary policy would raise interest rates and thereby reduce the value of the collateral and net worth of the borrowers. This, accordingly, limits the ability of borrowers to borrow and invest. Further, the literature also points out a direct connection between the balance sheet channel and housing demand by features such as down-payment requirements, up-front transaction costs and minimum income to interest payment ratios. However, empirical evidence suggests that effectiveness of the credit channel depends upon conditions such as existence of bank-dependent borrowers, for instance, small and low net worth firms (Gertler and Gilchrist, 1993 and 1994), substitution between retail and bulk deposits and ability of the central bank to constrain banks’ potential to lend.

Empirical work to draw inferences on the existence of the credit channel in India is rather limited. A recent study examining the impact of financial liberalisation shows that banks in general are constrained in their lending operations by the availability of insured deposits and these constraints are more severe for those banks that lend predominantly against collateral. In India more than eighty five per cent of bank lending is against collateral. This implies a potentially important influence of the bank lending channel. A very recent attempt in estimating the bank lending channel has brought out a number of facets of the transmission mechanism - by employing structural VAR methodology on monthly data for all the Indian scheduled commercial banks spanning from April 1993 to April 2002 (Pandit, et al, 2006). First, the study validates the existence of a bank lending channel in the Indian context. This implies that the central bank, while formulating monetary policy, is likely to encounter independent shifts in the loan supply. Second, evidence seems to point to the fact that large banks with a wider resource base can more successfully insulate their loan supply from contractionary policy shocks vis-à-vis small banks. Third, the quantitative instruments such as the cash reserve ratio (CRR) continue to be important along with the price instruments such as the Bank Rate. Finally, prudential regulations have an important role to play in influencing lending decisions of banks. In particular, the introduction of capital adequacy ratios has made banks more concerned with the risk-return profile of loans, since additional lending warrants augmenting of capital base in order to adhere to the regulatory capital standards.

References:

Bernanke, Ben, and A. Blinder. 1988. “Credit, Money and Aggregate Demand.” American Economic Review 135-139, May.

Bernanke, Ben, and M. Gertler. 1995. “Inside the Black Box: The Credit Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission.”

Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.9: 27-48.

Pandit, B.L., Ajit Mittal, Mohua Roy and Saibal Ghosh. 2006. “Transmission of Monetary Policy, and the Bank Lending Channel: Analysis and Evidence for India.” DRG Study No.

25 , Reserve Bank of India.

III. POLICY DEVELOPMENTS IN THE CREDIT MARKET IN INDIA

4.23 The credit market, with commercial banks as its predominant segment, has been the major source for meeting the finance requirements in the economy, both for the private sector and the Central and State Government enterprises. In addition to sharing of resources between the private and the public sectors, a significant proportion of credit by commercial banks is earmarked for the priority sector1 . For a few decades preceding the onset of banking and financial sector reforms in India, credit institutions operated in an environment that was heavily regulated and characterised by barriers to entry, which protected them against competition. The issue of allocation of bank resources among various sectors was addressed through mechanisms such as SLR, credit authorisation scheme (CAS), fixation of maximum permissible bank finance (MPBF) and selective credit controls. This regulated environment set in complacency in the manner in which credit institutions operated and responded to the customer needs. The interest rate played a very limited role as the equilibrating mechanism between demand and supply of resources. The resource allocation process was deficient, which manifested itself in poor asset quality. They also lacked operational flexibility and functional autonomy.

1 Priority sector comprises agriculture (both direct and indirect), small scale industries, small roads and water transport operators, small business, retail trade, professional and self-employed persons, state sponsored organisations for Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, education, housing (both direct and indirect), consumption loans, micro-credit, loans to software, and food and agro-processing sector.

2 Under Section 18 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949, all scheduled banks are required to maintain SLR, i.e., a certain proportion of their demand and time liabilities (DTL) as on the last Friday of the second preceeding fortnight as liquid assets (cash, gold valued at a price not exceeding the current market price or unencumbered approved securities valued at a price as specified by the Reserve Bank from time to time). Following the amendment of the Act in January 2007, the floor rate of 25 per cent for SLR was removed.

4.24 As part of financial sector reforms in the early 1990s, wide ranging reforms were introduced in the credit market with a view to making the credit institutions more efficient and healthy. The reform process initially focused on commercial banks. After significant progress was made to transform commercial banks into sound institutions, the reform process was extended to encompass other segments of the credit market. As part of the reform process, the strategy shifted from micro-management to macro level management of the credit market. These measures created a conducive environment for banks and other credit institutions to provide adequate and timely finance to different sectors of the economy by appropriately pricing their loan products on the basis of the risk profile of the borrowers.

4.25 Lending interest rates were deregulated with a view to achieving better price discovery and efficient resource allocation. This resulted in growing sensitivity of credit to interest rates and enabled the Reserve Bank to employ market based instruments of monetary control. The Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR2) has been gradually reduced to 25 per cent. The Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) was reduced from its peak level of 15.0 per cent maintained during 1989 to 1992 to 4.5 per cent of Net Demand and Time Liabilities (NDTL) in June 2003. The reduction in statutory preemptions has significantly augmented the lendable resources of banks. Although the Reserve Bank continues to pursue its medium-term objective of reducing the CRR, in recent years, on a review of macroeconomic and monetary conditions, the CRR has been revised upwards in phases to 6.5 per cent.

4.26 While the stipulation for lending to the priority sector has been retained, its scope and definition have been fine-tuned by including new items. Further, restrictions on banks’ lending for project finance activity and for personal loans were gradually removed in order to enable banks to operate in a flexible manner in the credit market. As part of the financial sector reforms, the regulatory norms with respect to capital adequacy, income recognition, asset classification and provisioning have been progressively aligned with international best practices. These measures have enhanced transparency of the balance sheets of banks and infused accountability in their functioning. Accounting standards and disclosure norms were also strengthened with a view to improving governance and bringing them in alignment with international norms. As part of the reform programme, due consideration has been given to persification of ownership of banking institutions for greater market accountability and improved efficiency. Accordingly, several public sector banks expanded their capital base by accessing the capital market, which diluted Government ownership. To provide banks with additional options for raising capital funds with a view to enabling smooth transition to Basel II, the Reserve Bank, in January 2006, allowed banks to augment their capital funds by issue of additional instruments.

4.27 With a view to enhancing efficiency and productivity through competition, guidelines were laid down for establishment of new banks in the private sector. Since 1993, 12 new private sector banks have been set up. Foreign banks have also been allowed more liberal entry. Considering the special nature of banks, guidelines on ownership and governance in private sector banks were also issued in February 2005 (Box IV.2). As a major step towards enhancing competition in the banking sector, foreign direct investment in the private sector banks is now allowed up to 74 per cent (including investment by FIIs), subject to conformity with the guidelines issued from time to time. A roadmap for foreign banks, articulating a liberalised policy consistent with the WTO commitments was released in March 2005. For new and existing foreign banks, it was proposed to go beyond the existing WTO commitment of 12 branches in a year.

4.28 A large magnitude of resources of credit institutions had become locked up in unproductive assets in the form of non-performing loans (NPLs). Apart from limiting the ability of credit institutions to recycle their funds, this also weakened them by adversely affecting their profitability. The Reserve Bank and the Central Government, therefore, initiated several institutional measures to recover the past dues to banks and FIs and reduce the NPAs. These were Debt Recovery Tribunals (DRTs), Lok Adalats (people’s courts), Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) and the Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) mechanism. Settlement Advisory Committees have also been formed at regional and head office levels of commercial banks. Furthermore, banks can also issue notices under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 2002 for enforcement of security interest without intervention of courts. Further, banks, Fls and NBFCs (excluding securitisation companies/ reconstruction companies) have been permitted to undertake sale/purchase of NPAs. Thus, banks and other credit institutions have been given a menu of options to resolve their NPA problems.

4.29 persification of credit risk is essential for expanding the flow of credit. Excessive concentration of lending to certain sectors leads to a higher risk burden. There are various options available for sharing of risk. Asset securitisation allows banks to conserve regulatory capital, persify asset risks and structure products to reflect investors’ preferences (IMF, 2006). There are various instruments for sharing and transferring credit risk. One such instrument is asset securitisation (Box IV.3).

4.30 With a view to ensuring healthy development of the securitisation market, the Reserve Bank issued guidelines on securitisation of standard assets on February 1, 2006 to banks, financial institutions and non-banking financial companies.

4.31 Comprehensive credit information, which provides details pertaining to credit facilities already availed of by a borrower as well as his repayment track record, is critical for the smooth operations of the credit market. Lack of credit history is an important factor affecting the credit flow to relatively less creditworthy borrowers. In the absence of credit history, pricing of credit can be arbitrary, the perceived credit risk can be higher and there can be adverse selection and moral hazard. Accordingly, a scheme for disclosure of information regarding defaulting borrowers of banks and financial institutions was introduced. In order to facilitate sharing of information relating to credit matters, a Credit Information Bureau (India) Limited (CIBIL) was set up in 2000 (Box IV.4).

4.32 Most of the reform measures initiated for commercial banks such as deregulation of lending interest rates, prudential norms relating to capital adequacy/asset classification provisioning, and NPAs management were also extended to other credit institutions as well with some modifications as appropriate.

Box IV.2

Credit Market Reforms

Lending Interest Rates

• Lending interest rates of commercial banks were deregulated in October 1994 and banks were required to announce their prime lending rates (PLRs).

• The Reserve Bank mooted the concept of benchmark prime lending rate (BPLR) on April 29, 2003 to address the need for transparency in banks’ lending rates as also to reduce the complexity involved in pricing of loans.

• Banks now are free to prescribe respective BPLRs, as also lend at sub-BPLR rates.

• Banks are also permitted to offer floating rate loan products linked to a market benchmark in a transparent manner.

Term-lending by Banks

• Various restrictions on term loans by banks were gradually phased out by 1997. In terms of the guidelines prevailing before the initiation of economic reforms in 1991, banks were expected to extend term loans for small projects in participation with the State level institutions, though it was not mandatory.

• For large projects, however, they were allowed to participate compulsorily in participation with all-India FIs, subject to the condition that the share of the banking system would be restricted to 25 per cent of term loan assistance from banks and FIs and the aggregate term finance from the banking system could not exceed Rs.75 crore.

Asset Classification and Provisioning, and Capital Adequacy

• In terms of asset classification and provisioning norms prescribed in 1994, banks are required to classify assets into four categories, viz., standard assets, substandard assets, doubtful assets and loss assets, with appropriate provisioning requirements for each category of assets.

• The concept of ‘past due’ in the identification of non-performing assets (NPAs) was dispensed with effective from March 2001, and the 90-day delinquency norm was adopted for the classification of NPAs with effect from March 2004.

• As a major step towards tightening of prudential norms from the year ended March 2005, an asset is required to be classified as doubtful if it remains in the sub-standard category for 12 months as against the earlier norm of 18 months. Banks are now required to make provisioning against standard assets to the tune of 0.40 per cent except for certain specified sectors. These include direct advances to agriculture and SME sectors (0.25 per cent), residential housing loan beyond Rs.20 lakh (1.0 per cent) and personal loans (2.0 per cent). (In case of specified sectors, the general provisioning requirement increased from 0.4 per cent to 1.0 per cent in May 2006 and further to 2.0 per cent in January 2007).

• Banks were advised to adopt graded higher provisioning in respect of: (a) secured portion of NPAs included in 'doubtful' for more than three years category; and (b) NPAs which have remained in 'doubtful' category for more than three years as on March 31, 2004. Provisioning ranging from 60 per cent to 100 pre cent over a period of three years in a phased manner, from the year ended March 31, 2005 has been prescribed. However, in respect of all advances classified as 'doubtful for more than three years' on or after April 1, 2004, the provisioning requirement has been stipulated at 100 per cent. The provisioning requirement for unsecured portion of NPAs under the above category was retained at 100 per cent.

• Banks were subject to capital adequacy norms in 1994, according to which, banks were required to maintain capital to risk weighted asset ratio of 8 per cent. Subsequently, the ratio was raised to 9 per cent in 1999.

Exposure Limits

• Regulatory limits on banks’ exposure to individual and group borrowers in India were prescribed to avoid concentration of credit

• The applicable limit is 15 per cent of capital funds in the case of a single borrower and 40 per cent in the case of a group of borrowers. Credit exposure to borrowers belonging to a group may exceed the exposure norm of 40 per cent of bank’s capital funds by an additional 10 per cent (i.e., up to 50 per cent), provided the additional credit exposure is on account of extension of credit to infrastructure projects. Credit exposure to a single borrower may exceed the exposure norm of 15 per cent of bank’s capital funds by an additional 5 per cent (i.e., up to 20 per cent). In addition, banks may, in exceptional circumstances, with the approval of their boards, consider enhancement of the exposure to a borrower up to a further 5 per cent of capital funds.

Competition Enhancing Measures

• Public sector banks were allowed to raise capital from the equity market up to 49 per cent of the paid-up capital.

• A comprehensive policy framework was laid down on February 28, 2005 for ownership and governance in private sector banks. The broad principles underlying the framework ensure that : (i) ultimate ownership and control is well persified; (ii) important shareholders are ‘fit and proper’; (iii) directors and CEO are ‘fit and proper’ and observe sound corporate governance principles; (iv) private sector banks maintain minimum capital (initially Rs.200 crore, with a commitment to increase to Rs.300 crore within three years)/net worth (Rs.300 crore at all times) for optimal operations and for systemic stability; and (v) policy and processes are transparent and fair.

Box IV.3

Asset Securitisation

Securitisation is a process through which illiquid assets are transformed into a more liquid form of assets and distributed to a broad range of investors through capital markets. The lending institution’s assets are removed from its balance sheet and are instead funded by investors through a negotiable financial instrument. The security is backed by the expected cash flows from the assets.

Securitisation as a technique gained popularity in the advanced countries in the 1970s. Favourable tax treatment, legislative enactments, establishment of Government-backed institutions that extend guarantees, and a pragmatic regulatory environment appear to have contributed to the successful development of this market. Securitisation involves pooling similar assets together in a separate legal entity or special purpose vehicle (SPV) and redirecting the cash flows from the asset pool to the new securities issued by the SPV. The SPV is a device to ensure that the underlying assets are insulated from the risks of default by the originator of the assets. In general, there are two main advantages of securitisation. First, it can turn ordinary illiquid assets into reasonably liquid instruments. Second, it can create instruments of high credit quality out of debt of low credit quality.

Securitisation is designed to offer a number of advantages to the seller, investor and the debt market. For the seller or originator, securitisation mainly results in receivables being replaced by cash, thereby improving the liquidity position. It removes the assets from the balance sheet of the originator, thus, freeing capital for other uses, and enabling restructuring of the balance sheet by reducing large exposures or sectoral concentration. It facilitates better asset liability management (ALM) by reducing market risks resulting from interest rate mismatches. The process also enables the issuer to recycle assets more frequently and thereby improves earnings. For investors, securitisation essentially provides an avenue for relatively lower risk investment. Credit enhancement provides an opportunity to investors to acquire good quality assets and to persify their portfolios. From the point of view of the financial system as a whole, securitisation increases the number of debt instruments in the market, and provides additional liquidity in the market. It also facilitates unbundling, better allocation and management of project risks. It widens the market by attracting new players due to availability of superior quality assets.

Securitisation, however, if not carried out prudently can leave risks with the originating bank without allocating capital to back them. The main risk for a bank arises if a true sale has not been achieved and the selling bank is forced to recognise some or all of the losses if the assets subsequently cease to perform. Also, funding risks and constraints on liquidity may arise if assets designed to be securitised have been originated, but because of disturbances in the market, the securities cannot be placed. There is also a view that there is at least a potential conflict of interest if bank originates, sells, services and underwrites the same issue of securities.

Reference:

BIS. 2006a. Quarterly Review, June.

4.33 The credit derivatives are gaining increasing popularity in many countries. Since the early 1990s, there has been proliferation of different types of credit derivatives in several countries (Box IV.5).

Box IV.4

Credit Information Bureaus

Credit bureaus (or credit reference agencies) are useful as they help lenders to assess credit worthiness of individual borrowers and their ability to pay back a loan. As credit bureaus collect and collate personal financial data on individuals from financial institutions, a form of price discrimination can be modelled taking into account credit rating and past behaviour of borrowers. The information is generally aggregated and made available on request to contributing companies for the purposes of credit assessment and credit scoring. Establishment of credit information bureaus can facilitate in obtaining the credit history of the borrowers and, thus, help the banks in correctly assessing the creditworthiness.

The CIBIL provides a vital service, which allows its members to make informed, objective and faster credit decisions. CIBIL’s aim is to fulfill the need of credit granting institutions for comprehensive credit information by collecting, collating and disseminating credit information pertaining to both commercial and consumer borrowers, to a closed user group of members. Banks, financial institutions, non-banking financial companies, housing finance companies and credit card companies use CIBIL’s services. Data sharing is based on the principle of reciprocity, which means that only members who have submitted all their credit data, may access Credit Information Reports from CIBIL.

With a view to strengthening the legal mechanism and facilitating credit information companies to collect, process and share credit information on borrowers of banks/FIs, a draft Credit Information Companies (Regulation) Bill was passed in May 2005 and notified in June 2005. The Government and the Reserve Bank have framed rules and regulations for implementation of the Act, with specific provisions for protecting individual borrower’s rights and obligations. The rules and regulations were notified on December 14, 2006. In terms of the provisions of the Act, after obtaining the certificate of registration from the Reserve Bank to commence/carry on business of credit information companies will be able to collect all types of credit information (positive as well as negative) from their member credit institutions and disseminate the same in the form of credit reports to the specified users/individuals.

4.34 The risk management architecture of banks in India has strengthened and they are on the way to becoming Basel II compliant, providing adequate comfort level for the introduction of credit derivatives. Accordingly, the Reserve Bank, as part of the gradual process of financial sector liberalisation in India, permitted banks and primary dealers to begin transacting in single-entity credit default swaps (CDS) in its Annual Policy Statement for 2007-08 released on April 24, 2007.

Box IV.5

Credit Derivatives

A credit derivative is a contract (derivative) to transfer the risk of the total return on a credit asset falling below an agreed level, without transfer of the underlying asset. This is usually achieved by transferring risk on a credit reference asset. Early forms of credit derivatives were financial guarantees. Three common forms of credit derivatives are credit default swap (CDS), total return swap (TRS) and credit linked note (CLN). Credit derivatives are designed to allow independent trading/hedging of credit risk. It is also possible to transfer and/or transform credit risk through securitisation. Credit derivative is a logical extension of two of the most significant developments in the financial markets, viz., securitisation and derivatives.

A CDS consists of swapping, usually on an ongoing basis, the risk premium inherent in an interest rate on a bond or a loan in return for a cash payment that is made in the event of default by the debtor. The CDS has become the main driver of the credit derivatives market, offering liquid price discovery and trading on which the rest of the market is based. It is an agreement between a protection buyer and a protection seller, whereby the buyer pays a periodic fee in return for a contingent payment by the seller upon a credit event happening in the reference entity. The contingent payment usually replicates the loss incurred by creditor of the reference entity in the event of its default. It covers only the credit risk embedded in the asset, risks arising from other factors, such as interest rate movements, remain with the buyer.

A TRS – also known as total rate of return swap – is a contract between two counterparties, whereby they swap periodic payments for the period of the contract. Typically, one party receives the total return (interest payments plus any capital gains or losses for the payment period) from a specified reference asset, while the other receives a specified fixed or floating cash flow that is not related to the creditworthiness of the reference asset, as with a vanilla interest rate swap. The payments are based upon the same notional amount. The reference asset may be any asset, index or basket of assets. The TRS is simply a mechanism that allows one party to derive the economic benefit of owning an asset without use of the balance sheet, and which allows the other to effectively 'buy protection' against loss in value due to ownership of a credit assets.

While the CDS provides protection against specific credit events, the total return swap protects against the loss of value irrespective of cause, whether default and widening of credit spreads, among others.

A CLN is an instrument whose cash flow depends upon a credit event, which can be a default, credit spread, or rating change. The definition of the relevant credit events must be negotiated by the parties to the note. A CLN, in effect, combines a credit-default swap with a regular note (with coupon, maturity, redemption). Given its regular-note features, a CLN is an on-balance sheet asset, unlike a CDS.

Banks and the financial institutions derive at least three main benefits from credit derivatives. One, credit derivatives allow banks to transfer credit risk and hence free up capital, which can be used for other productive purposes. Two, banks can conduct business on existing client relationships in excess of exposure norms and transfer away the risks. For instance, a bank which has hit its exposure limits with a client group may have to turn down a lucrative guarantee deal. However, with credit derivatives, the bank can take up the guarantee and maintain its exposure limits by transferring the credit risk on the guarantee or previous exposures. This allows bank to maintain client relationships. Three, banks can construct and manage a credit risk portfolio of their own choice and risk appetite unconstrained by funds, distribution and sales effort.

However, the use of credit derivatives also raises some concerns. One, some of the credit derivatives, which are being used, are at their infancy and need to mature. Introduction of such products, therefore, may be potentially destabilising. Two, the measurement and management of credit risk is much more complicated than market risk. Third, documentation risk is an important aspect of credit derivatives. Fourth, certain incentive issues arise with the use of credit derivatives. This is because such instruments typically change the underlying borrower-lender relationship and establish new relationships between lenders that become risk shedders and the new risk takers. This new relationship has the potential for market failure due, for instance, to asymmetric information.

Reference:

The Reserve Bank of India. 2003. Report of Working Group on Introduction of Credit Derivatives in India (Convenor: B. Mahapatra). Mumbai, March.

IMF. 2002. Monetary and Financial Statistics Manual.

Ueda Kazuo. 2003. ‘On Credit Risk Transfer Instruments and Central Banks’. 18th Annual General Meeting, Tokyo, April.

IV. TRENDS IN CREDIT – THE 1990s AND ONWARDS

Credit Trends – All Institutions

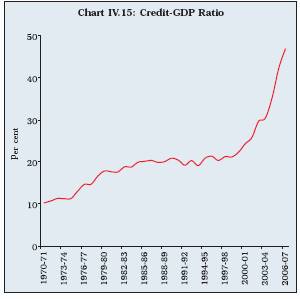

4.35 Total loans outstanding by all credit institutions (commercial banks, DFIs and cooperatives) combined together increased at a compound annual rate of 15.7 per cent during the 1990s and by 17.7 per cent per annum during the current decade so far (up to 2005-06). As percentage of GDP, loans outstanding increased from 34.2 per cent at end-March 1991 to 54.1 per cent at end-March 2006, suggesting increased credit penetration in the country (Table 4.1).

4.36 During the 1990s, the credit growth of commercial banks was lower than that of credit institutions in the co-operative sector. However, the trend has reversed during the current decade (up to 2005-06) with credit growth of commercial banks being significantly higher than the credit growth of the co-operative institutions. Credit growth of NBFCs during the first five years of the current decade was significantly lower than the growth of total credit by all institutions. Loans and advances by DFIs declined during the period from 2000-01 to 2005-06, essentially due to the conversions of two large DFIs into banks (Table 4.2).

4.37 Reflecting movements in growth rates, the share of commercial banks’ credit in total outstanding credit by all institutions increased significantly from 59.7 per cent at end-March 1991 to 78.2 per cent at end-March 2006. During the same period, the share of RRBs and SCARDBs also increased marginally. The share of all other credit institutions declined. Apart from aggressive retail lending strategies adopted by commercial banks, which captured some of the businesses of NBFCs, increased and persified lending into rural areas contributed to the rise in the share of commercial banks. Conversion of two DFIs into commercial banks also contributed to the increase in the share of commercial banks in the current decade and a sharp decline in the share of FIs (Table 4.3). In the case of co-operative institutions, which are financially weak and inadequately capitalised, reforms have been initiated very recently, which may help in reversing the declining share of co-operative institutions.

4.38 Since commercial banks account for more than three-fourths of total credit outstanding and detailed data on credit by other institutions are not readily available, analysis in the remaining part of the chapter is based largely on credit extended by scheduled commercial banks.

Table 4.1: Total Outstanding Credit by |

all Credit Institutions |

End-March |

Total Credit |

Annual |

Credit-GDP |

Outstanding |

Growth |

Ratio |

(Rs. crore) |

(Per cent) |

(Per cent) |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

1991 |

1,94,654 |

– |

34.2 |

1995 |

3,47,125 |

22.7 |

34.3 |

2000 |

7,25,074 |

17.1 |

37.1 |

2001 |

7,94,125 |

9.5 |

37.8 |

2002 |

8,93,384 |

12.5 |

39.2 |

2003 |

10,77,409 |

20.6 |

43.8 |

2004 |

11,99,607 |

11.3 |

43.4 |

2005 |

14,81,587 |

23.5 |

47.4 |

2006 |

19,28,336 |

30.2 |

54.1 |

Compound Annual Growth Rate (Per cent) |

1991 to 2000 |

|

15.7 |

|

2000 to 2006 |

|

17.7 |

|

Note: 1. Data are provisional.

2. Data include commercial banks, RRBs, LABs, DFIs, UCBs, STCBs, CCBs,

PACSs, SCARDBs and PCARDBs.

3. In case of non-availability of data for select co-operatives, data for the previous year have been repeated.

Source : Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India, various issues, Reserve Bank of India. |

Table 4.2: Institution-wise Growth of |

Outstanding Credit |

(Compound Annual Growth Rate) |

(Per cent) |

Category |

1991-92 to |

2000-01 to |

1999-2000 |

2005-06 |

1 |

|

2 |

3 |

1. |

Commercial Banks |

15.8 |

23.0 |

2. |

RRBs (and LABs) |

15.4 |

21.1 |

3. |

Financial Institutions |

14.2 |

-5.9 |

4. |

Urban Cooperative Banks |

21.4 |

7.3 |

5. |

State Cooperative Banks |

16.3 |

7.6 |

6. |

District Central Cooperative Banks |

16.0 |

10.3 |

7. |

Primary Agricultural Credit Societies |

17.9 |

9.3 |

8. |

SCARDBs |

27.0 |

7.5 |

9. |

PCARDBs |

15.9 |

9.1 |

All Institutions |

15.7 |

17.7 |

Note : Data are provisional.

Source : Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India, variousissues, Reserve Bank of India. |

Table 4.3: Distribution of Credit – |

Category-wise Share |

(Per cent) |

Category |

End-March |

|

|

1991 |

2006 |

1 |

|

2 |

3 |

1. |

Commercial Banks |

59.7 |

78.2 |

2. |

RRBs (and LABs) |

1.8 |

2.1 |

3. |

All-India Financial Institutions |

24.9 |

5.8 |

4. |

Urban Co-operative Banks |

4.1 |

3.6 |

5. |

State Co-operative Banks |

3.4 |

2.1 |

6. |

District Central Co-operative Banks |

6.0 |

4.2 |

7. |

Primary Agricultural Credit Societies |

3.3 |

2.5 |

8. |

SCARDBs |

0.7 |

0.9 |

9. |

PCARDBs |

1.0 |

0.7 |

All Institutions |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Note : Data are provisional.

Source : Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India, various issues, Reserve Bank of India. |

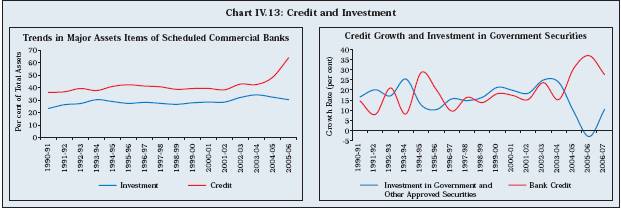

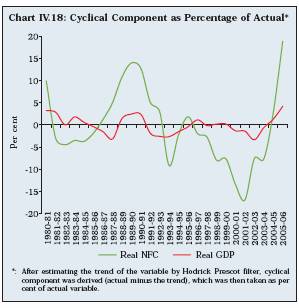

Trends in Scheduled Commercial Bank Credit

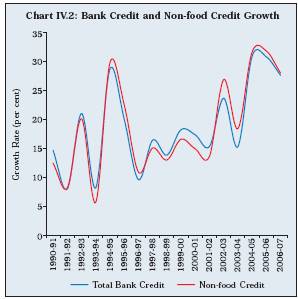

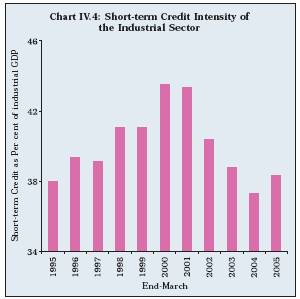

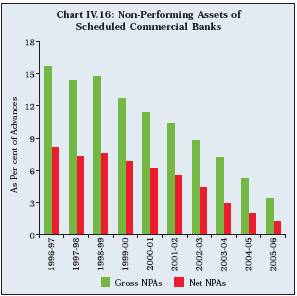

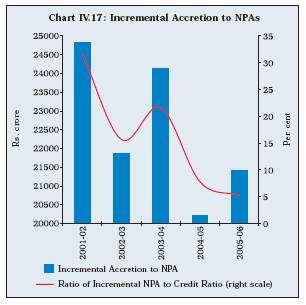

4.39 Bank credit, after witnessing an erratic pattern in the first half of the 1990s, showed a deceleration from 1996-97 to 2001-02, growing at an average annual rate of 15.1 per cent as compared with 19.5 per cent in the preceding four years (Chart IV.2). Several factors, both on the demand and the supply sides, contributed to the contraction of credit. On the supply side, introduction of prudential norms relating to income recognition, asset classification and provisioning in the mid-1990s made banks cautious. Application of norms revealed large gross NPAs with banks (15.7 per cent of their gross advances at end-March 1997). Banks, therefore, became wary of enlarging their loan portfolio. The relatively high level of NPAs, in particular, had a severe impact on weak banks. Banks’ capacity to extend credit was also impaired due to little headroom available in the capital adequacy ratio (8.7 per cent at end-March 1996). Banks found risk-adjusted returns on government securities more attractive. Hence, despite lowering of statutory preemption in the form of SLR, banks continued to invest in government securities, far in excess of the requirements. Banks’ investment in SLR securities at end-March 1996 was 36.9 per cent of net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) as against the statutory requirement of 31.5 per cent. Banks’ investments in SLR securities remained more or less at that level (36.7 per cent) by end-March 2002, even as the SLR was brought down significantly to 25 per cent.

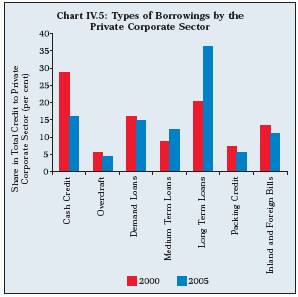

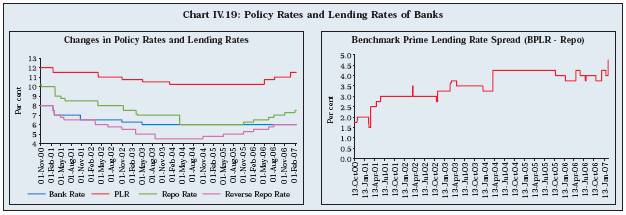

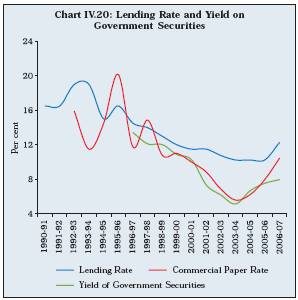

4.40 On the demand side also, several factors contributed to the decline in demand for credit by the corporate sector. The industrial sector witnessed massive expansion in capacity in certain sectors, especially cement and steel, in the initial phase of reforms. However, as the quantitative restrictions were removed and import tariffs reduced, the corporate sector faced intense competition during the latter part of the 1990s. The focus of the corporate sector, thus, shifted from expanding capacity to restructuring and the industrial sector slowed down significantly. The average annual growth rate of industrial production was 5.2 per cent during 1996-97 to 2001-02 as compared with 9.4 per cent in the preceding three years. This affected the demand for credit by the corporate sector. Increased competition also forced corporates to restructure their balance sheets, whereby they increased their reliance on retained earnings and reduced their borrowings. This was evident from the debt-equity ratio, which declined from an average of 85.5 per cent during 1990-91 to 1994-95 to 65.2 per cent during 1995-96 to 1999-2000 (see Table 7.5 of Chapter VII).

4.41 Although the Reserve Bank pursued accommodative monetary policy during this period (1996-97 to 2001-02) by reducing the CRR and the policy rates, viz., the Bank Rate and the reverse repo rate (the then repo rate), credit offtake did not pick up. Downward stickiness of nominal interest rates on the one hand, and falling inflation rate on the other, led to a significant rise in real interest rates. The average real lending rates of banks increased to 12.5 per cent during 1996-97 to 2001-02 as against 6.5 per cent during 1990-91 to 1995-96 (Mohan, 2003). This also appeared to have contributed to slackness in credit expansion.

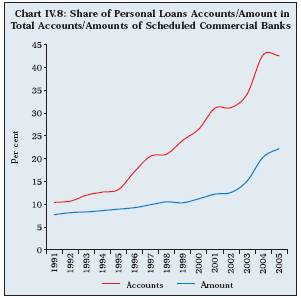

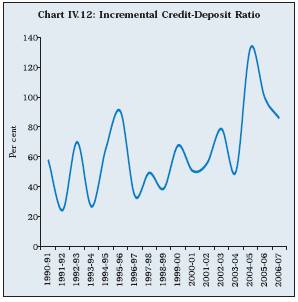

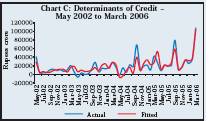

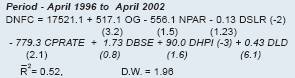

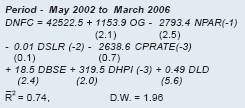

4.42 Credit growth accelerated in 2002-03 only to decelerate sharply in 2003-04 even when the industrial sector was buoyant due mainly to contraction in food credit and increased recourse by corporates to internal sources of financing and increased external commercial borrowings. During 2004-05 to 2006-07, bank credit expanded at a robust pace of around 30 per cent. Major factors that contributed to the acceleration in credit growth were pick-up in economic growth, improvement in asset quality of the credit institutions, moderation in inflation and inflation expectations, decline in real interest rates, rising income of households and increased competition with the entry of new private sector banks (as detailed in the subsequent sections). The removal of restrictions on retail credit and project finance by banks also created new sources of credit demand.

Sectoral Deployment of Credit

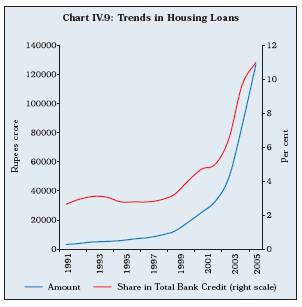

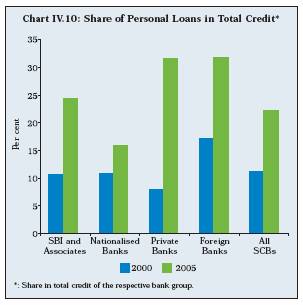

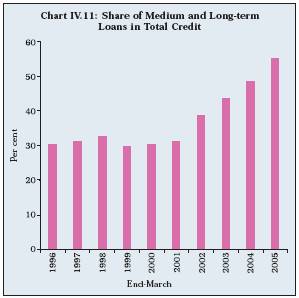

4.43 Reforms and the evolving economic structure had a profound impact on the flow of bank credit to various sectors of the economy during the 1990s and the current decade. Credit growth to agriculture during the 1990s slowed down to almost one-half as compared with the 1980s (Table 4.4). However, the trend was reversed beginning from 2002-03 as a result of concerted efforts made by the Reserve Bank and the Government to increase the flow of credit to agriculture. Credit to the industrial sector slowed down, albeit marginally, in the 1990s and the current decade as compared with the 1980s. A significant development during the current decade, however, has been the rapid credit expansion to the household sector (personal loans) in the form of housing and other retail loans.

Table 4.4: Sector-Wise Credit of Commercial Banks – Compound Annual Growth Rate |

(Per cent) |

Period |

Agriculture |

Industry |

Transport

Operators |

Professional

Services |

Personal

Loans |

Trade |

Finance |

Total Bank

Credit |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

1980-81 to 1989-90 |

18.1 |

17.4 |

13.6 |

20.7 |

25.3 |

11.8 |

29.2 |

17.2 |

1990-91 to 1999-00 |

10.6 |

15.4 |

9.4 |

16.8 |

22.7 |

17.3 |

25.6 |

16.0 |

2000-01 to 2004-05 |

22.2 |

15.9 |

11.2 |

30.4 |

37.7 |

12.6 |

27.4 |

20.2 |

Memo: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

End-March |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2001 |

13.3 |

10.6 |

7.7 |

31.3 |

27.7 |

25.0 |

21.0 |

17.0 |

2002 |

23.7 |

14.9 |

7.1 |

44.0 |

25.1 |

12.7 |

42.2 |

21.8 |

2003 |

18.6 |

14.1 |

0.9 |

22.4 |

38.1 |

3.2 |

34.6 |

15.2 |

2004 |

26.7 |

8.1 |

18.7 |

29.5 |

57.2 |

-2.5 |

16.4 |

16.4 |

2005 |

29.2 |

33.5 |

22.8 |

25.8 |

42.9 |

27.8 |

24.3 |

30.9 |

Source: Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks, various issues, Reserve Bank of India. |

|

|

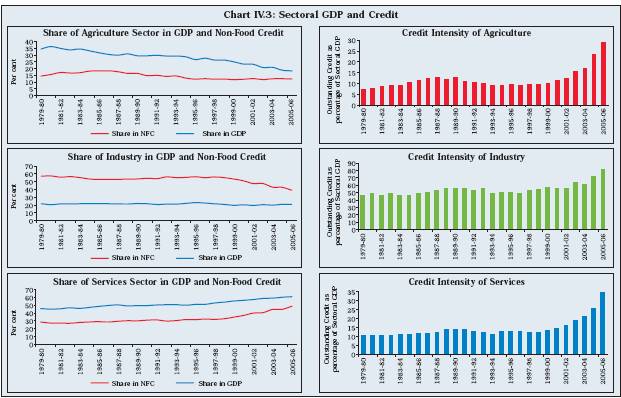

4.44 The share of agriculture and industrial sectors in total bank credit declined between end-March 1990 and end-March 2005, while that of personal loans and professional services increased sharply.

Agriculture

4.45 As a result of the sharp deceleration in the growth of credit to agriculture, the share of agriculture in total bank credit declined sharply from 15.9 per cent at end-March 1990 to 9.6 per cent by end-March 2001 (Table 4.5). During this period, however, the share of agriculture in GDP also declined significantly. As a result, credit intensity of the agriculture sector (credit to agriculture sector as percentage of sectoral GDP) remained broadly at the same level. In the early part of the current decade, the Government and the Reserve Bank took a series of measures to facilitate the flow of credit to the agriculture sector. These, inter alia, included: (i) rescheduling of short-term loans to medium and long-term loans, following agricultural distress in several parts of the country; (ii) higher targets fixed under the Special Agricultural Credit Plans of public sector banks and making it applicable to private sector banks also; and (iii) advising banks to double the flow of credit within three years starting from 2004-05. Credit growth to agriculture picked up significantly from 2003-04 onwards. The share of agricultural credit in total bank credit also increased to 10.8 per cent by end-March 2005. The gap between the share of agriculture credit in total bank credit and its share in GDP narrowed down to less than 8 percentage points at end-March 2006 from 17.4 per cent at end-March 1995. Furthermore, credit intensity of the agriculture sector increased sharply from 11.1 per cent in 2001-02 to 27.0 per cent by 2005-06 (Chart IV.3). The number of borrowal accounts in the agriculture sector also increased to 26.66 millions in 2004-05 from 19.84 millions in 2000-01.

Table 4.5: Distribution of Outstanding Credit of Scheduled Commercial Banks |

(Per cent to total credit) |

|

End-March |

Sector |

Mar-90 |

Mar-95 |

Mar-00 |

Mar-01 |

Mar-02 |

Mar-03 |

Mar-04 |

Mar-05 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

Agriculture |

15.9 |

11.8 |

9.9 |

9.6 |

9.8 |

10.0 |

10.9 |

10.8 |

Industry |

48.7 |

45.6 |

46.5 |

43.9 |

41.4 |

41.0 |

38.0 |

38.8 |

Transport |

3.2 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

Personal Loans and Professional Services |

9.4 |

11.3 |

14.4 |

15.8 |

16.8 |

19.6 |

25.3 |

27.0 |

of which: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loans for Purchase of Consumer Durables |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

Loans for Housing |

2.4 |

2.8 |

4.0 |

4.7 |

5.0 |

6.5 |

9.7 |

11.0 |

Trade |

13.9 |

17.1 |

15.6 |

16.6 |

15.4 |

13.8 |

11.5 |

11.2 |

Financial Institutions |

2.1 |

3.8 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

5.7 |

6.7 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

Miscellaneous / All Others |

6.8 |

8.5 |

7.1 |

7.5 |

9.5 |

7.7 |

6.2 |

4.6 |

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Basic Statistical Returns of Scheduled Commercial Banks in India, various issues, Reserve Bank of India. |

Trends in Priority Sector Advances

4.46 Prior to the nationalisation of banks in 1969, banks’ lending was confined primarily to big business and trading in the metropolitan and urban centres. After the nationalisation of banks, the Government of India undertook corrective measures to rectify the lopsided lending by banks. Accordingly, in 1972, banks were advised to extend credit to certain activities, known as the priority sectors. With a view to aligning bank credit to the changing needs of society, the scope and definition of the priority sector have been continuously fined-tuned by including new items as also by enhancing credit limit of the constituent sub-sectors (Box IV.6).

Box IV.6

Policies Relating to the Priority Sector, Micro-finance and Credit Cards in Rural Areas

Priority Sector

• Domestic scheduled commercial banks and foreign banks are required to extend a minimum of 40 per cent and 32 per cent, respectively, of their net bank credit (NBC) to the priority sector with sub-targets set for lending to various sub-sectors.

• Major categories of priority sector credit include agriculture and allied activities, small scale industries, housing loans and education loans, among others.

• The scope of the priority sector has been expanded over the years to include export activity, education, housing, software industry, venture capital, leasing and hire purchase.

Micro-finance

• The SHG-bank linkage programme, launched in India in 1992 as a pilot project, envisages (i) rganizing the rural poor into Self-help Groups (SHGs); (ii) building their capacities to manage their own finances; and (iii) then negotiating bank credit on commercial terms.

• The target-group broadly comprises small and marginal farmers, landless agricultural and non-agricultural labourers, artisans and craftsmen, and other rural poor engaged in small businesses such as vending and hawking.

• There are two major models under micro-finance, namely, Self-Help Group-Bank Linkage (SHG-BL) and Micro-Finance Institutions (MFIs).

Kisan Credit Card

• The Kisan Credit Card (KCC) scheme, introduced in August 1998, enables farmers to purchase agricultural inputs and draw cash for their production needs.

• The Scheme was revised in November 2004 to cover term credit as well as working capital for agriculture and allied activities, in addition to short-term credit limits available separately for crop/s.

• Short-term credit/crop loans as well as working capital for agriculture and allied activities are repayable in 12 months, while term loans are repayable within a maximum period of 5 years, depending on the type of activity/investment.

• The Scheme is being implemented by all commercial banks, RRBs, state co-operative banks/DCCBs/PACS and scheduled primary co-operative banks.

General Credit Card

• The guidelines on general credit cards (GCC) were issued on December 27, 2005, with a view to providing easy credit to banks’ customers in rural areas.

• The objective of the GCC scheme is to provide hassle-free credit to the customers of banks based on the assessment of cash flow without insistence on security, purpose or end-use of the credit. This is in the nature of overdraft or cash-credit with no end-use stipulations.

• GCC may not necessarily be in the form of a card and can be issued in the form of a Pass Book, if the holder of GCC desires to operate cash withdrawals from bank branch.

• The credit facility extended under the scheme is in the nature of revolving credit. The GCC holder is entitled to draw cash up to the limit sanctioned from the specified branch of the bank.

• Banks have the flexibility to fix the limit on GCC based on the assessment of income and cash flow of the entire household. However, total credit facility under GCC for an individual should not exceed Rs.25,000 and interest rate on the facility may be charged, as considered appropriate and reasonable.

• Banks may utilise the services of local post offices, schools, primary health centers, local government functionaries, farmers’ association/club, well-established community-based agencies and civil society organisations for sourcing of borrowers for issuing GCC.

• To incentivise the banks to issue GCC, fifty per cent of credit outstanding under GCC, up to Rs.25,000, is eligible for being treated as indirect agricultural financing for the purpose of priority sector target.

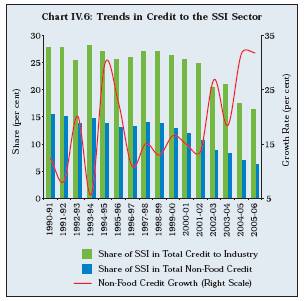

4.47 Credit growth to the priority sector showed a distinct improvement in recent years growing at an average annual rate of 25.7 per cent during the period from 2000-01 to 2005-06 as compared with 13.1 per cent during the 1990s. This was mainly due to increased lending to cer tain sectors such as agriculture and housing. Despite this increase, priority sector advances declined from 40.1 per cent of non food gross bank credit (NFGBC) at end-March 1990 to 36.3 per cent by end-March 2006 (Table 4.6). With higher credit growth during 2004-05 and 2005-06 by both public and private sector banks, the priority sector credit target of 40.0 per cent of net bank credit (NBC) was achieved by end-March 2006.

4.48 Within the priority sector, credit to agriculture, which grew at an average annual rate of 11.2 per cent during the 1990s, accelerated to 25.7 per cent during the six-year period ended March 2006. Despite this increase, the share of agriculture in total priority sector advances declined from 40.9 per cent at end-March 1990 to 33.8 per cent at end-March 2006 (Table 4.6). The share of agricultural loans as per cent of NBC of public sector banks was at 15.3 per cent at end-March 2005 and 15.2 per cent at end-March 2006. The agriculture loans as per cent of NBC of private sector banks at 13.5 per cent each at end-March 2005 and 2006 were, much, lower than the stipulated target of 18 per cent. Some banks, especially new private sector banks and foreign banks, lack adequate branch network in rural areas as a result of which some of these banks find it difficult to achieve their priority sector credit targets. To address the problem, banks were asked to make deposits, to the extent of shortfall, in the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) of the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) for achieving the lending target. Foreign banks are required to make deposits in the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI).

4.49 For increasing the flow of credit to agriculture and other rural sectors of the economy, several innovative measures were initiated in the form of Self-Help Group (SHG) - Bank Linkage programme and Kisan Credit Card (KCC) schemes. Micro-finance is now increasingly being recognised as a cost effective and sustainable way of expanding outreach of the banking sector to the rural poor. The relative absence of interest subsidies, the high repayment performance and reduced transaction costs to lenders are some of the major advantages of micro-finance. There is now a growing realisation among the lending agencies that micro-finance programmes are bankable, creditworthy and profitable. Banks are now discovering that people at the bottom of the pyramid can be brought into their business models.

4.50 The SHG-Bank Linkage programme is one of the two models of micro-finance. The flow of credit to the rural sector is hampered for two reasons. One, credit is largely collateral based, and two, loan delinquencies are generally higher. Formation of joint liability groups in the form of SHGs helps in overcoming both these problems. The responsibility for repayment of the loan is borne jointly by all the members of SHGs, who are engaged in some economic activity that generates the income needed for the repayment. Experience of SHGs in countries such as Bangladesh also shows that loan delinquency is lower in the case of SHGs due to peer pressure. The main advantages of the program are on-time repayment of loans to banks; reduction in transaction costs for both, the poor and the banks; door-step savings and credit facilities available to the poor; and exploitation of the untapped business potential in rural India.

Table 4.6: Trends in Outstanding Priority Sector Advances |

(Amount in Rs. crore) |

|

Total Priority Sector Advances |

Agriculture Advances |

SSI Advances |

End-March |

Amount |

Annual

Growth

(Per cent) |

Per cent of

NFGBC |

Amount |

Annual Growth

(Per cent) |

Per cent of

NFGBC |

Amount |

Annual

Growth

(Per cent) |

Per cent of

NFGBC |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

1990 |

40,383 |

18.0 |

40.1 |

16,526 |

18.5 |

16.4 |

15,543 |

18.3 |

15.4 |

1991 |

42,915 |

6.3 |

37.8 |

16,750 |

1.4 |

14.8 |

17,181 |

10.5 |

15.1 |

1992 |

45,425 |

5.8 |

37.4 |

18.157 |

8.4 |

15.0 |

18,150 |

5.6 |

15.0 |

1993 |

49,832 |

9.7 |

35.5 |

19,963 |

9.9 |

14.2 |

20,026 |

10.3 |

14.3 |

1994 |

53,880 |

8.1 |

36.9 |

21,208 |

6.2 |

14.5 |

22,617 |

12.9 |

15.5 |

1995 |

64,161 |

19.1 |

34.7 |

23,983 |

13.1 |

13.0 |

27,638 |

22.2 |

15.0 |

1996 |

73,329 |

14.3 |

33.0 |

27,044 |

12.8 |

12.2 |

31,884 |

15.4 |

14.4 |

1997 |

84,880 |

15.8 |

33.8 |

31,442 |

16.3 |

12.5 |

35,944 |

12.7 |

14.3 |

1998 |

99,507 |

17.2 |

34.6 |

34,869 |

10.9 |

12.1 |

43,508 |

21.0 |

15.1 |

1999 |

1,14,611 |

15.2 |

35.2 |

39,634 |

13.7 |

12.2 |

48,483 |

11.4 |

14.9 |

2000 |

1,31,827 |

15.0 |

35.1 |

44,381 |

12.0 |

11.8 |

52,814 |

8.9 |

14.1 |

2001 |

1,54,414 |

17.1 |

36.0 |

51,922 |

17.0 |

12.1 |

56,002 |

6.0 |

13.0 |

2002 |

1,75,259 |

13.5 |

36.3 |

60,761 |

17.0 |

12.6 |

57,199 |

2.1 |

11.8 |

2003 |

2,11,609 |

20.7 |

34.1 |

73,518 |

21.0 |

11.9 |

60,394 |

5.6 |

9.7 |

2004 |

2,63,834 |

24.7 |

36.2 |

90,541 |

23.2 |

12.4 |

65,855 |

9.0 |

9.0 |

2005 |

3,81,476 |

44.6 |

38.2 |

1,25,250 |

38.3 |

12.5 |

74,588 |

13.3 |

7.5 |

2006 |

5,09,910 |

33.7 |

36.3 |

1,72,292 |

37.6 |

12.3 |

90,239 |

21.0 |

6.4 |

Average Annual Growth (Per cent) |

1990 to 2000 |

|

13.1 |

|

|

11.2 |

|

|

13.6 |

|

2001 to 2006 |

|

25.7 |

|

|

25.7 |

|

|

9.5 |

|

NFGBC: Non Food Gross Bank Credit.

Source: Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Economy, 2005-06, Reserve Bank of India. |

4.51 The Self-Help Group (SHG)-Bank Linkage programme has emerged as an important model of micro-finance activity in the country (see Box IV.5). As at end-March 2006, 2.2 million SHGs were linked to banks with cumulative bank loans amounting to Rs.11,398 crore (Table 4.7). The share of commercial banks in financing SHGs has increased over the years. The number of families assisted has increased by about five-fold from 5 million in 2001 to 24 million in 2005. Further, the average bank loan per SHG increased from Rs.18,227 in 2001 to Rs.32,012 in 2005.

4.52 The SHG-Bank Linkage programme, which till now has been concentrated largely in the Southern States, is expected to gain further ground with the NABARD taking up a programme for intensification of these activities in 13 identified States, accounting for 70.0 per cent of the rural poor population.