| This Chapter is divided into two parts. Part – I sets the tone under the broad theme of “Enabling Regulations for Market Access and Financial Stability”. Part-II deals with various stability and developmental issues related to financial sector regulation. Part I

Enabling Regulations for Market Access and Financial Stability Positioning the regulatory stance amidst the need for healthy innovation and financial inclusion, remains the main challenge for India’s financial sector regulation. While the underpinnings of financial market regulation need to recognise that financial markets are inherently risky, the approach to regulatory interventions needs to be in tune with the developments on the ground. The broad theme of “Enabling Regulations for Market Access and Financial Stability” envisions a balanced, predictable, institution-neutral, ownership-neutral and technology-neutral regulatory regime for India’s financial system, wherein financial market participants are not discouraged to take risks, as long as those risks are required, sufficiently acknowledged and provided buffers for. 3.i A lax approach to financial sector regulation in developed financial markets was recognised as one of the major contributing factors which eventually led to the global financial crisis (GFC). While the ‘global’ crisis resulted in the need for a ‘coordinated’ and ‘harmonised’ regulatory response under the aegis of G20, the wide range of regulatory reforms were primarily aimed at addressing the shortcomings observed in the regulatory approach in jurisdictions with relatively more advanced financial system. Thus advanced economies (AEs) needed to look into the extant regulatory practices to address the excesses committed by the ‘industry’, mainly the big financial institutions driving the international financial markets. 3.ii In the process, the emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have had to contend with regulatory practices that were too complex but formed part of the global agenda, to serve the need for ‘consistency’ in formulation and implementation of such reforms, even as the suitability of some of the global regulatory reforms for the EMDEs is still being discussed. While it is important for the EMDEs to learn from the mistakes of others, they need much simpler regulatory approaches given their not so complex financial systems and also in view of the need to expand and extend the coverage and reach of the financial system in the prevailing levels of under-penetration of the financial services. 3.iii While allowing them to thrive, regulation needs to keep a watch on the markets and evolve with time by continuously learning and updating the skill sets. However, regulation also has a cost as do the ‘market failures’ and resulting crises. While assessing the cost impact on the system of a specific regulation is complex, measuring the benefits of regulation is equally challenging. Therefore, while the ‘non-occurrence’ of crises may indicate that the regulation was able to avoid ‘excesses’, it cannot be an adequate indicator for establishing its effectiveness, especially considering its potential impact on innovation. The inherent fallacy and ‘survival bias’ ingrained in such conclusions may compromise the need for a real paradigm shift in the approach to regulation. 3.iv While innovation influences regulation, regulation too affects innovation, both positively and negatively. The ‘compliance innovation’ occurs when the scope of the regulation is broad and the resulting innovation remains within the scope of regulation. On the other hand, the ‘circumventive innovation’ occurs when the scope is narrow and the resulting innovation allows regulated entities to move out of the regulatory perimeter.1 For example, as observed in the Indian context in the recent past, certain financial sector entities changed their organisational form to avoid being covered by relatively stricter regulations for entities that raise deposits from the public. An appropriate regulatory stance in such circumstances could be minimising the cost of compliance for those who are willing to comply while making it more difficult and costlier for those who want to circumvent the regulation. 3.v Any new regulation, which may generally be preceded by some degree of uncertainty may work through three dimensions: stringency, flexibility and information. While ‘stringency’ of regulation denotes the degree of change in the compliance burden, ‘flexibility’ refers to the authority structure of the regulation (‘command’ and ‘control’ regulations versus ‘incentives based’ regulation) and the ‘information’ dimension of regulation points to the degree by which new regulations promote complete information or whether they induce more uncertainty. An effective regulatory approach should ultimately result in strengthening market access and market functioning, which build on and encourage innovation.1* 3.vi Considering that risk taking is inherent and essential in financial markets, the current Indian regulatory stance envisions a balanced, predictable, institution-neutral, ownership-neutral and technology-neutral regulatory regime for the entire financial system, wherein banks and other financial intermediaries are not discouraged to take risks as long as those risks are required, sufficiently acknowledged and provided buffers for. This stance also envisages a push towards being more proactive in identifying risks and once identified, being prompt about taking steps in mitigating and managing those risks. The next question in this context relates to the desirable pace of effecting regulatory changes; whether it should be through ‘big bang’ reforms that may come with major market disruptions or approaching the goal through a gradual, less disruptive ‘moving target’ strategy. 3.vii The move towards risk based supervision (RBS) with more granular and credible data collection processes will help in the optimal use of scarce supervisory resources. However, even RBS cannot be expected to track all the risks which hide and reside beyond and between the gaps in data and rules. A supervisory approach not constrained by rules should ideally cover a comprehensive oversight of regulated institutions for ensuring that they effectively manage their own risks regardless of whether or not those risks are covered by prudential rules or standards. Thus, the focus needs to be on an ‘expert’ rather than a ‘legal’ model of regulation. As regulatory agencies start from a pre-existing view or regulatory goal, the initial regulatory stance is based on past practices, habits and cultural norms. This, in turn, determines the nature of regulatory activities that are undertaken. In an alternative approach, regulators design their regulatory interventions through which they first identify and define the key risk issues and then target regulatory interventions around those issues rather than automatically following a standard supervisory process.2 Role of financial sector in economic growth 3.viii The issues relating to the desirable approach to regulation, rate of growth and innovation in the financial sector need to be addressed in the context of its raison d’etre of supporting real sector economic growth and development. A more developed financial sector is expected to be more efficient in allocating resources and thereby promoting economic development. The causation also works in the reverse direction, as economic growth itself generates demand for financial services and spurs financial sector development. 3.ix Even as the potential role of the financial sector in growth is well appreciated, it may be misleading to conclude that unbridled financial sector growth and development will continue to support economic growth in a positive monotonic way.3 The positive effect on economic growth begins to decline beyond a certain level of financial development while costs in terms of economic and financial volatility begin to rise.4 As India may yet be far from that threshold level of financial development (Chart 3.i), where diminishing returns start to set in, the approach to regulation may need to be suitably tailored. On the other hand, fundamental discipline and sound credit culture need to be protected and cannot be sacrificed at the altar of short term targets of growth, as a more credible and strong financial system will aid in promoting more sustainable growth in the long run. 3.x The underpinnings of financial market regulation, hence, need to be based on the understanding that markets are inherently unstable and that prudential regulations have their limitations. As markets are known and have proved to be ‘imperfect’, effective regulation may help to a large extent in addressing some such imperfections arising from an informational asymmetry. Regulation should thus aim to promote the market mechanism while also ensuring that the outcome of the marketplay remains aligned with the broader goals of maximising efficiency for all stakeholders. The bottom line 3.xi As it has now been acknowledged internationally that the regulatory environment needs to vary with the cycle, this approach towards a balanced and predictable regulatory regime will be informed by the structure and current state of financial sector development, the depth and breadth of financial markets, phases of economic and credit cycles and immediate domestic priorities. Accordingly, there is a need to design ‘cycle-proof’ regulations aimed at creating stability through the cycle. For this, regulations should be comprehensive, contingent and cost effective.5 These aspects with a background of some recent developments on the regulatory and supervisory fronts form the narrative of part II of this chapter. Part II

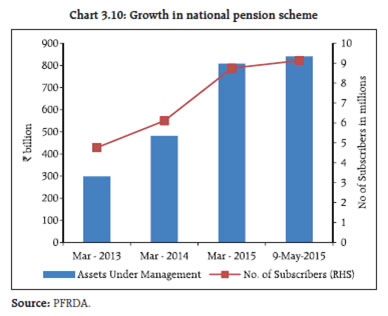

Financial Sector in India – Regulation and Development The financial sector regulatory reforms in India are being driven by the domestic priorities, within the spirit of the global regulatory standards, even as the challenges in uniform implementation of the reforms are coming to the fore, in many jurisdictions. While the regulatory move towards encouraging greater market access and market discipline will help the development of domestic financial markets, the issues related to asset quality and capital levels of public sector banks (PSBs) call for greater attention by various stakeholders, notwithstanding the regulatory intent towards incentivising early recognition of the weaknesses and prompt joint action. The concerns emanating from rapid rise in algorithmic and high frequency trading in recent years highlight the need for caution for India’s securities markets, even as significant steps have been taken with regard to move towards risk based supervision, preventing and dealing with illegal money-raising activities and insider trading. Agricultural insurance needs urgent focus in the wake of frequent episodes of weather related calamities and their impact on small and marginal farmers. There is a need for harmonising the regulation of the physical commodities market and strengthening the linkages between the derivatives markets and physical (cash) markets, mainly in agricultural commodities. The expected shifts in demography in coming decades call for attention to old age income security. The Atal Pension Yojana (APY) operationalised by the Government, is expected to strengthen the social security for the large working population in unorganised sector. Developments in international regulations 3.1 With the near completion of the formulation6 and standard-setting stages of the post-crisis international financial regulatory reforms agenda, the focus has now firmly shifted to full, consistent and prompt implementation of reforms that were agreed upon. With a view to addressing new risks and vulnerabilities, work programmes have been outlined by the Financial Stability Board (FSB) to address financial stability risks stemming from marketbased finance including those associated with asset management activities and addressing misconduct risks and withdrawal from correspondent banking. Progress in the implementation of the international regulatory reforms agenda 3.2 India’s record on adopting the international regulatory reforms and standards for banking capital and liquidity regulation has been consistent and in some aspects Reserve Bank’s regulatory framework (including higher minimum capital ratios and higher risk weightings for certain types of exposures) has been observed to be even more conservative than the Basel framework. The recently published assessment reports by Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), on the implementation of the Basel riskbased capital framework and the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) for India as part of the ongoing Regulatory Consistency Assessment Program (RCAP) for its member jurisdictions has rated the standards adopted by the Reserve Bank with regard to riskbased capital requirements as ‘compliant’ with the minimum Basel capital standards. Each of the 14 components of the Basel capital framework included in the assessment has been assessed as ‘compliant’. Implications of uneven progress in implementation across jurisdictions 3.3 However, as had been broadly anticipated and also mentioned in previous Financial Stability Reports (FSRs), progress on the implementation of the agenda has been uneven and varied with respect to different reforms in different jurisdictions guided by different national priorities. Even as implementation in several key areas of globally agreed reforms and standards requires significant movement forward, regulators—both collectively at the global level as well as independently at the national levels—face new challenges for fulfilling the aspirations of growth, equity and stability of domestic economies amidst growing complexities and uncertainties related to the global economic and financial environment. 3.4 In this regard, an important consideration for regulators in EMDEs like India is that even with increasingly integrated financial markets and notwithstanding the progress made on international co-operation on regulation and policymaking under G-20, regulators and policymakers in many jurisdictions, mainly in the advanced economies (AEs), have been observed to focus on the needs of domestic growth and stability. While the pursuit for even greater international co-operation and coordination should continue, domestic regulation will need to address the challenges arising from spill-over effects of stresses and strains resulting from volatility and other events, as also the priorities for financial sector regulation specific to the national context within the spirit of the internationally agreed upon regulatory standards. Regulatory and developmental issues in the Indian financial system Banking sector 3.5 The banking system plays a predominant role in the Indian financial system, and as has been observed, most of the risks in the system tend to eventually find a way to the banking system.7 Thus, the need for stronger capital markets—both equity and corporate debt—is also linked with the imperative of relieving some of the excess burden on the banking system as more liquid and developed markets will help in achieving a clear separation between market risks and banking system credit risks. However, a buoyant secondary market in equity as witnessed during 2014-15, the primary equity and debt markets have not reflected the same optimism (Chart 3.1). Enlisting the banking sector for developing corporate bond markets 3.6 There have been some significant steps for furthering the development of corporate bond markets, including some innovative measures for roping in the banking sector in its role as a potentially large issuer. The issuance of long term bonds by banks to raise resources for lending to long term projects in infrastructure sub-sectors and in affordable housing are further encouraged with exemptions from certain regulatory pre-emptions (the cash reserve ratio and the statutory liquidity ratio on banks’ demand and time liabilities and mandatory lending towards priority sectors).8 Apart from leveraging the positioning of banks, especially PSBs, as quasi-sovereign issuers of long term bonds, there is a possibility for considering other tools like linking long term credit approvals with a mandatory part to be raised through issuances9 of bonds by corporate entities and partial credit enhancements by banks to bonds issued by corporate entities. However, for achieving the desired results from the efforts aimed at developing corporate debt markets there is a need to significantly improve the liquidity in secondary markets, from curent levels (Chart 3.2). Focus on the asset quality of the banking sector 3.7 The broad regulatory approach of the Reserve Bank over the last year has been on supporting and strengthening the banking sector through measures aimed at enhancing credit discipline, addressing asset quality issues, encouraging market access, enabling earlier recognition of stress and appropriate solutions and improving corporate governance and strategies to augment capital. In July 2014, the Reserve Bank introduced a flexible financing scheme allowing banks to extend long term loans of 20- 25 years to match the cash flows of projects while refinancing them every five or seven years. 3.8 However, the regulatory initiatives will need to be sensitive to the currently prevailing emphasis on the asset quality, mainly of public sector banks (PSBs) and concerns related to banks’ ability to raise long term funding in the current stage of development of debt market. Furthermore, concerns related to potential asset-liability mismatches and other practical aspects involved in the provisions enabling flexible financing by banks for long term project loans to infrastructure and other core sectors with ‘resetting’ of loan terms need to be adequately addressed.10 Effectiveness of ‘debt restructuring’ mechanisms 3.9 Previous FSRs highlighted the importance of an objective and dispassionate assessment of the effectiveness of the performance of the corporate debt restructuring (CDR) mechanism. The CDR mechanism mainly resorted to by PSBs, was perceived to be aligning lenders’ interests in favour of deferral of accounting recognition of underlying risks rather than effective restructuring resulting in opacity about the quality of the loan book thus seriously impacting market valuations of banks. As some of the restructured accounts had come up for another round of restructuring, the overall effectiveness of CDR mechanism needed to be reviewed against its intended objective of ‘amicably and collectively evolve policies and guidelines for working out debt restructuring plans in the interests of all concerned.‘11 3.10 In addition to its easy accessibility, the strong preference of borrowers for CDR might have had its roots in their tendency to protect their promoterequity from impairment, given the relatively weaker bankruptcy law in the country. Accordingly, the regulatory focus has intensified with regard to the need for separating the cases of ‘wilful default’ from other cases of delinquencies caused by ‘genuine’ economic or business factors. 3.11 Recognising the moral hazard in perpetuating regulatory forbearance, the Reserve Bank removed the distinction between restructured and nonperforming assets effective April 1, 2015. Recent trends in the number of cases and aggregate amount of debt referred and approved under the CDR cell shows the effect of withdrawal of regulatory forbearance on restructuring, especially with respect to large credit accounts (Chart 3.3). 3.12 The revised framework of the Joint Lenders Forum (JLF), along with the Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) aim to address these issues by incentivising early identification of problems, timely restructuring of loans which are viable and taking prompt steps for recovery or sale if they are found to be unviable (Box 3.1). Concomitantly, the asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) have been permitted to consider an extended resolution period of eight years, subject to certain conditions, with respect to stressed assets which are under a restructuring proposal approved by Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) or CDR or JLF.12 Protecting lenders’ interests through strategic debt restructuring 3.13 Learning from the experience with the CDR, the regulations dealing with restructuring of corporate debt have been modified with a view to enabling a change of management at the borrower companies, when the operational/ managerial inefficiencies are observed to be one of the reasons behind the continuation or aggravation in the stress being felt at the borrower company. In line with the general principle that the shareholders bear the first loss rather than the debt holders, the ‘restructuring’ mechanisms need to include provisions for transferring equity of the company by promoters to the lenders as compensation for their sacrifices, further infusion of promoter-equity and transfer of the promoters’ equity holdings to a security trust till ‘turnaround’ of company.  3.14 Under the strategic debt restructuring (SDR) mechanism13, in order to achieve the change of ownership/management at the borrower company, the consortium of banks and financial institutions / lenders under the JLF may collectively become the majority shareholder by converting their dues into equity, subject to the statutory limit set under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. Supporting the efforts and through prompt inter-regulatory coordination, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has issued notification regarding fixing of conversion price and lock-in period and providing for necessary exemptions for banks from the takeover rules thus allowing them to convert debt to equity of companies, under SDR, without having to make mandatory tender offers to minority shareholders.14 Box 3.1: Revised framework for dealing with the asset quality of large credit The Central Repository of Information on Large Credits (CRILC) has been set up in the Reserve Bank to collect, store and disseminate information on borrowers enjoying exposure of ₹50 million and above from banks/ non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) and insurance companies. Lenders have been provided access to the CRILC database to view individual borrower-wise consolidated exposure data. CRILC has been assigned a pivotal role in activating and coordinating the mechanism to manage stressed assets as envisaged in the Stressed Asset Framework (January 30, 2014) and the operational instructions issued subsequently. In order to capture early warning signals of financial stress faced by borrowers, the framework requires banks to create a sub-asset—Special Mention Accounts (SMA) and classify borrowers under three SMA categories (SMA-0, SMA-1 and SMA-2) as under: SMA Sub- categories | Basis for classification | SMA-0 | Principal or interest payment not overdue for more than 30 days but account showing signs of incipient stress | SMA-1 | Principal or interest payment overdue between 31-60 days | SMA-2 | Principal or interest payment overdue between 61-90 days | Banks are required to form JLF as soon as an account with an aggregate exposure of ₹1,000 million and above is reported as SMA-2 to CRILC. JLF is also mandatorily required to be formed when a borrower request lender/s, with substantiated grounds, for formation of a JLF on account of imminent stress in accounts with aggregate exposure of ₹1,000 million and above. Lenders also have the option of forming a JLF even when the aggregate exposure is less than ₹1,000 million and /or when the account is reported as SMA-0 or SMA-1. Framework for dealing with loan frauds 3.15 Rising trends in loan related frauds in the financial sector are a matter of serious concern for regulators and the government. The Reserve Bank has notified a framework15 for dealing with loan frauds with the objective of directing the focus of banks on aspects relating to detection, reporting and monitoring, while ensuring that conduct of normal business by the banks and their risk taking abilities are not adversely impacted. The framework suggests that while the Reserve Bank will take care of the concerns till the detection of a fraud (for all banks), the government could focus on the post-detection stage (for PSBs) involving law enforcement agencies. 3.16 The framework envisages continuous monitoring of loan accounts as a fraud preventive tool with checks at different stages of the loan life cycle and identification of red flagged accounts (RFAs) based on early warning signals for accounts above ₹500 million and classification of RFAs either as fraud or otherwise within six months. Further, the framework also requires reporting of RFAs/frauds on the Reserve Bank’s CRILC for dissemination amongst banks and a decision on the fraud status by JLF in case of consortium/multiple banking arrangements. Capital needs of banks—Conservation versus augmentation of capital 3.17 PSBs have traditionally played a predominant role in the Indian financial and banking system notwithstanding their falling share in total deposits and advances of the banking system (Chart 3.4). The performance of PSBs will remain crucial in the present context even as the structure, competitiveness and composition of the Indian banking system is poised to change in the coming months with the entry of new types of entities. 3.18 Even though the jury is still out on efficiencyredundancy debates over an apparently unending capital requirement for the banking industry, the pitfalls of the framework for capital that was based on risk weights and the need to ensure caps for leverage and additional capital buffers have generally been appreciated. Close on the heels of the efficiencyredundancy trade-off comes the safety-efficiency trade-off, the manifestation of which can be seen in the public-private sector bank paradigm in India. In terms of public perception PSBs, with implicit government support, are considered to be relatively immune to destabilising impacts though it has an efficiency imperative, when judged by their returns on asset or capital employed. However, the same sense of safety eludes PSBs when it comes to their valuations. With the Indian government thinking of new performance based norms for capital infusion, this disconnect is sought to be addressed. There may be a notion, albeit an incomplete one, that with the government deciding on performance based parameters for identifying banks which deserve fiscal support, those that are not up to the mark might find it even more difficult to raise capital. Market ‘view’ of bank capital 3.19 In an environment where the capital needs of PSBs have to be predominantly met by the market, there is a need to clearly define the contours of an effective regulatory and oversight regime which reduces the informational asymmetry and thereby promotes market access. In a broad sense, such a regulatory regime is required to embrace less discretion in terms of classification of assets and provisioning for expected losses which render reported information on non-performing assets (NPAs) and profitability inadequate. In the absence of better information, markets are prone to take enabling provisions to be emblematic of across the board problems and tend to have a ‘PSB discount’ attached to their market-valuations (Chart 3.5). Capital adequacy versus capital planning 3.20 The rules for minimum regulatory capital requirements for banks in India are more stringent, as compared to Basel framework and other major jurisdictions. However, perhaps, there is a need to go beyond the regulatory perspective based on numerical compliance on the capital requirements and capital adequacy, as the perception of the ‘market’ about banks’ capital levels may be equally important consideration, especially with respect to the PSBs. Meeting regulatory prescriptions on capital adequacy is to take care of the current business portfolio whereas markets with their forward looking bias look at capital planning which in a way is an indication of the future growth planning of a bank. On the other hand, in a stressed scenario, capital constraints along with a need to protect margins may even impair banks’ abilities to transmit policy rate signals.  3.21 A significant gap in capital to risk-weighted ratios (CRAR) of two sets of banks (Chapter II, Chart 2.3) with fairly divergent financial performances gives the ‘impression’ of a dualistic approach to capital adequacy and might be seen by the market as a sign of weakness rather than strength of the PSBs. While regulatory capital adequacy represents the floor, the actual assessment of capital adequacy should ideally include the component addressing Pillar 2 risks as also the capabilities of banks for opportunistic fund raising according to market conditions and their needs which in effect will require proactive capital planning and management. 3.22 In any case, a more market oriented approach does not imply sacrificing distributional objectives. It rather emphasises best execution of such objectives by leveraging technology, evaluating the marginal value of businesses (illustratively, the ‘value’ of overseas business units or focus on line of business, say ‘retail’) and a transparent accountability framework. Furthermore, a reorientation of the performance evaluation of the top management (chief executives) of PSBs so as to specifically incorporate stock market valuations will reduce ‘principal-agent’ problems inherent in such a relationship and will also reflect the true marginal cost of capital relevant for recapitalisation. 3.23 As capital infusion for PSBs by the government is also about committing tax payers’ money, this calls for enhanced efficiency and capital conservation rather than an equitable distribution of scarce capital. On the other hand, while there is no dispute over the need for buffering banks with adequate capital, this may not ensure asset quality and hence the overall strength of the balance sheet (Box 3.2). Accounting profits and efficiency in cash generation 3.24 Analysing bank balance sheets might have become complex given the nature and extent of the mandates for disclosures. Thus, it becomes imperative that disclosures do not deflect the focus of investors and analysts, out of context. The more complex the business models adopted by banks get, the more exhaustive the disclosures become, though simple cash flows may be a better indicator of the true health of banks. 3.25 Accounting measures of a bank’s profitability are generally constructed based on net profit (profit after tax). However, apart from the other limitations of accounting profits in reflecting the true economic profitability of banks, some specific accounting dispensations may also create a divergence between the economic reality of underlying transactions and the way they are reflected in financial statements (accounting profits). Therefore, a robust measure of ‘cash profit’ (cash generated from business / operating activities of banks) could provide more useful information regarding the overall efficiency of the banks, to the users and stakeholders. 3.26 Cash profit of any business entity can be deduced from ‘cash flow from operations’ statement. However, in case of banks and other financial companies, the distinction between cash flow from ‘operating’ activities and ‘financing’ or ‘investment’ activities gets blurred. An ideal ‘cash profit’ calculation for a bank should adjust for all non-cash charges, accrual items and valuation gains and losses, which will require substantially granular and intensive data. However, in the absence of such detailed information, the earnings before provisions and tax (EBPT) can be tracked, with a view to capturing the ‘essence’ of the measure in a tractable way. Although there are other important non-cash items, provisions are the most significant non-cash charges for banks and in case of some banks they show sharp movements, on year-on-year basis. Box 3.2: Does augmentation of capital reduce risk? Post-crisis there has been a thrust on increasing bank capital and reducing excessive leverage. The other side of this story, though less appreciated, is that if banks are unable to augment capital they must reduce the size of their balance sheets. The question that arises in this context is whether augmentation of capital is going to reduce risks for banks. In a research that is still in progress Robert C. Merton (Merton 2014) asserts that even if banks replace their lost capital to retain the same level of leverage, they still become riskier than before. According to Merton, risky debt is nothing but risk-free debt minus guarantee of debt. In other words, an investor in risky debt performs two activities—risk-free lending and insurance writing. Drawing an analogy from ‘options’, Merton shows that this insurance/guarantee writing is nothing but writing a put option. Through this analogy it may be seen that the value of the guarantee is inversely related to the value of the asset. But given the convex nature of the relation between this guarantee and the asset, the risk is not linearly changing (Chart 3.A). In other words, as asset value declines a bank becomes much more risky. As a result, the asset declines in value several times even if the positions (exposures) have not increased. The paper brings more insights to the clustering of high sigma events, saying that two sigma with a five times larger slope looks like ten sigma with a constant slope. It is all about recognising the convexity. When sovereigns explicitly or implicitly guarantee (according to Merton, sovereigns almost always guarantee their banks, either explicitly or implicitly), it adds another layer of guarantee to what banks as lenders have already underwritten while undertaking risky lending; it is nothing but guarantors writing guarantees of their own guarantors. When banks ultimately make a mistake in their lending decisions and if the borrower/asset fails, the banks themselves become worse credits with the sovereign being a guarantor itself becoming weaker. If the banks substantially hold government debt, the feedback loop becomes stark. It may thus be seen that the connectedness between banks and sovereigns is a potent propagation channel of macro-financial risk. Merton’s piece of advice to banks is that they must ask themselves that by extending a particular loan and writing the associated guarantee, to what extent are they exposed to the risk associated with the assets that support the credit. On the other hand sovereigns need to be aware of the potential risks that may take them by surprise when they materialise, due to their perceived, if not real, interconnectedness with the banking system.  Reference: Merton, Robert C. (2014), ADB’s Distinguished Speakers Program Measuring the Connectedness of the Financial System: Implications for Risk Management. © Asian Development Bank. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11540/4102. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO 3.27 An analysis based on a simplified framework of earnings before provisions and taxes (EBPT) and profit before tax (PBT) and corresponding ratios (EBPT/average advances and investments and EBT/ average advances and investments) point towards divergent trends in accounting and EBPT. At the bank group level, the divergence between these two measures has increased for PSBs and decreased for private sector banks over the last five years (Charts 3.6 ‘a’ and ‘b’). There may be a need to give more importance to the cash generation capabilities of banks’ assets since the value of a firm is equal to discounted free cash flows. Urban co-operative banks Size, regulation and systemic risks 3.28 The regulatory approach to urban co-operative banks (UCBs) has been tailored recognising their role and mandate for providing financial services to the less privileged sections of the population.16 Although co-operatives are intended to remain small with their activities limited to their membership, a license to carry on the banking business provides UCBs unlimited access to public deposits. With the liability of members (shareholders) restricted to membership shares, owners become the users of resources predominantly contributed by nonmembers leading to conflict of interest that needs to be moderated through regulation and supervision. 3.29 Some large multi-state urban co-operative banks (MS-UCBs) have, over the years, attained balance sheet sizes comparable to those of small private sector commercial banks. A comparison of the top 5 UCBs with that of the five smallest private sector commercial banks indicates that in terms of deposits, advances and total assets some UCBs have business and asset sizes more than those of small private banks (Chart 3.7).  3.30 Weak corporate governance of UCBs has been a major issue plaguing the sector which together with lack of access to market for capital, has been a significant factor resulting in liquidation of many UCBs. As ‘co-operatives’ come under the domain of states17, the Reserve Bank does not have the same level of control on the management of UCBs, as it has in respect of scheduled commercial banks (SCBs).18 While the existing resolution powers available with the regulators (imposing a moratorium and facilitating voluntary and/or compulsory mergers with stronger financial institutions), have served the purpose so far, these may not be sufficient to deal with the failure of a large and complex institution. Thus, there is a need for improving the governance, capitalisation and resolution mechanism in cooperative banking. 3.31 In view of the possible implications of UCBs for systemic risks, a committee has been constituted to re-examine and recommend appropriate set of businesses, size, conversion and licensing terms and other related aspects for the UCBs.19 Non-banking financial sector 3.32 In addition to banks, most of the other types of financial entities in the organised sector (deposit-accepting non-banking finance companies, mutual funds, insurance companies, pension funds and intermediaries in securities and commodity markets) come under the purview of a designated regulator. Non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) as a broad category generally cover a broad spectrum of entities and activities and are associated with the notion of shadow banking. However, NBFCs meeting the minimum criteria for registration are under regulation of the Reserve Bank. The deposit accepting NBFCs (NBFCs-D) and other NBFCs deemed as systemically important among the non-deposit accepting NBFCs (referred to as NBFCs-ND-SI) are subject to relatively tougher prudential regulations. The regulatory framework for NBFCs was revised in late 2014 with emphasis on further harmonising and strengthening the prudential norms for these NBFCs. Shadow banking—Different shades in the Indian context 3.33 As highlighted in previous FSRs, while the size of the shadow banking sector in India20 is substantial with significant levels of interconnectedness with the banking system, risks emanating from this sector are not of the same shade and magnitude as observed in other major jurisdictions. India’s financial system is characterised by low penetration of banking and other financial services and is much less complex in terms of financial products. In view of the relatively wide regulatory oversight, the concerns from the shadow banking sector as experienced in advanced financial markets may not be fully valid for developing markets like India. 3.34 For India, the concerns in this regard mainly relate to a large number of small entities with varying activity profiles working in the organised or unorganised sector outside the regulatory purview. Previous FSRs have raised possible system risks from unregulated financial entities and unauthorised financial activities in the organised and unorganised sectors, especially in view of the possibility of public perception and mis-information about them being under regulation, which may give rise to consumer protection issues. Such issues, with their frequency of occurrence even if scattered and heterogeneous across time and geography, may take the shade of a systemic stability issue through the ‘trust’ channel. These events may have significant other socioeconomic implications, especially when they affect sections of the lower-income strata of the population and may compromise the success of efforts towards financial inclusion. Therefore, the challenge for regulators and state agencies is keeping a watch on and having a measure of the scale and nature of activities and developments in this sector. Action against illegal money raising funds 3.35 The mushrooming of illegal money-raising funds in the last few years and their failure to provide the ‘returns’ promised to investors have been a source of concern with potential to cause systemic stress. In this context, SEBI has significantly cracked down on various unregistered collective investment schemes (CIS)/deemed public issue (DPI) in the last year. 3.36 Some unlisted companies are luring retail investors by issuing securities including nonconvertible debentures/non-convertible preference shares in the garb of private placement without complying with legal provisions and relevant SEBI regulations. As part of punitive and preventive action with respect to such activities, SEBI has issued orders against errant schemes/entities and has advised investors through caution notes to avoid investing in illegal CIS and DPIs.21 In addition to this, investors have been advised to verify whether such entities have filed offer documents/applications with any recognised stock exchange for listing. Companies are also cautioned not to issue securities to public without complying with provisions of the law. 3.37 Under the initiative of the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC), several steps have been taken to make SLCCs more effective for better dissemination of market intelligence with regard to unauthorised deposit schemes and CIS. Accordingly, SLCCs meet at quarterly intervals and are chaired by the Chief Secretary of state Government / Administrator of Union Territory. The FSDC sub-committee takes stock of the activities of SLCCs on a half- yearly basis and the discussions cover subjects such as progress regarding enactment of the Protection of Interests of Depositors (PID) Act, information- sharing and investor awareness programmes. Financial inclusion Financial inclusion plans of banks 3.38 As discussed in the earlier sections of this chapter, the regulatory focus of different countries will be different given the different socio-economic circumstances and different stages of financial sector development. Thus, for EMDEs like India, the role and functioning of financial sector need to be viewed, not only from the perspective of promoting growth and stability, but also in terms of ‘distributional equity’. 3.39 Indian development planning has focused on formulation of programmes and policies aimed at promoting social and financial inclusion. The disbursement of financial benefits needs a systematic channel which will provide for financial empowerment and make monitoring easier and the local government bodies more accountable. The ‘Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana’ (PMJDY) launched in August 2014 and the ‘RuPay Card’ - a ‘payment’ solution, are important schemes in this regard. These two schemes are complementary and will enable achievement of multiple objectives of financial inclusion, insurance penetration, and digitalisation. 3.40 Financial inclusion plans (FIPs) submitted by banks which are duly approved by their boards form part of the business strategies of banks. These plans have facilitated changing the perspective of banks towards financial inclusion from a mere social obligation to a viable business opportunity. These plans have proved to be an effective tool for monitoring the impact of the efforts made towards financial inclusion. The comprehensive financial inclusion plans capture data relating to progress based on various parameters including basic savings bank deposit accounts (BSBDAs), small credits and business correspondent-information and communication technology) (BC-ICT) transactions. 3.41 There was considerable increase in the total number of banking outlets, opening of BSBDAs and small credits during 2014-15 (Table 3.1), because of the government’s initiative under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY). While a rapid increase in the number of bank account holders in the country since the launch of PMJDY is a strong indicator of result-oriented efforts on financial inclusion, this momentum needs to be translated into meaningful improvement in penetration of banking and credit facilities, especially in rural areas. Financial safety nets: Deposit insurance 3.42 The evolution of the global financial crisis (GFC) showed the importance of maintaining depositor confidence in the financial system and the key role that deposit protection plays in maintaining this confidence. The crisis underscored the need to increase deposit insurance coverage and strengthening of funding arrangements to enhance financial stability. The International Association of Deposit Insurers (IADI) and the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) issued ‘Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems’ in June 2009, which underwent revision in November 2014. A compliance assessment methodology for the core principles was released in December 2010. The core principles and their compliance assessment methodology are used by jurisdictions as a benchmark for assessing the quality of their deposit insurance systems and for identifying gaps in their deposit insurance practices and measures to address them. | Table 3.1: Progress on financial inclusion by banks since 2010 and during 2014-15 | | Particulars | Year ended March 10 | Year ended March 14 | Year ended March 2015 | Progress April 14 - March 15 | | Banking Outlets in Villages – Branches | 33,378 | 46,126 | 49,965 | 3,839 | | Banking Outlets in Villages – BCs | 34,174 | 333,845 | 499,587 | 165,742 | | Banking Outlets in Villages - Other Modes | 142 | 3,833 | 4,552 | 719 | | Banking Outlets in Villages – Total | 67694 | 383,804 | 554,104 | 170,300 | | Urban Locations covered through BCs | 447 | 60,730 | 96,847 | 36,117 | | BSBDA-Through branches (Number) | 60.2 | 126.0 | 210.2 | 84.2 | | BSBDA-Through branches (Amount) | 44.3 | 273.3 | 363.7 | 90.4 | | BSBDA-Through BCs (Number) | 13.3 | 116.9 | 187.8 | 70.9 | | BSBDA-Through BCs (Amount) | 10.7 | 39.0 | 74.6 | 35.6 | | BSBDA-Total (Numbers) | 73.5 | 243.0 | 398.0 | 155.0 | | BSBDA Total (Amount) | 55.0 | 312.2 | 438.3 | 126.0 | | OD facility availed in BSBDAs (Number) | 0.2 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 1.7 | | OD facility availed in BSBDAs (Amount) | 0.1 | 16.0 | 19.9 | 3.9 | | KCCs -Total (Number) | 24.3 | 39.9 | 42.6 | 2.6 | | KCCs -Total (Amount) | 1,240.0 | 3,684.5 | 4,430.3 | 745.8 | | GCCs-Total (Number) | 1.4 | 7.4 | 9.2 | 1.8 | | GCCs-Total (Amount) | 35.1 | 1,096.9 | 1,301.6 | 204.7 | | ICT A/Cs-BC-Total Transaction (Number) | 26.5 | 328.6 | 477.0 | 477.0 | | ICT A/Cs-BC-Total Transactions (Amount) | 6.9 | 524.4 | 859.8 | 859.8 | OD - Overdraft, GCCs - General credit cards, KCCs- Kisan credit cards

Note: All amounts in ₹ billion. Number of units in millions.